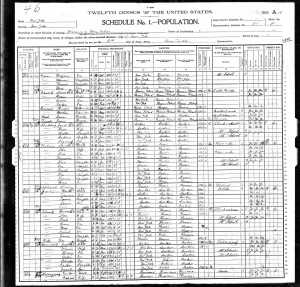

In the course of researching Abraham Rosenzweig’s life, I discovered a tenth child born to Gustave and Gussie Rosenzweig. On the 1910 census there were nine children, all but one born in New York City between 1888 and 1904. (Lillian, the first child, was born in Romania around 1884.) There were four boys, Abraham, Jacob/Jack, Harry and Joseph, and five girls, Lillian, Sarah, Rebecca, Lizzie and Rachel. The NYC birth index covers those years, so I started my research of Abraham by looking for a birth record. I had several records indicating that he was born sometime around 1890, but I could not (and still have not) found a record for Abraham’s birth.

I expanded my search to look for any Rosenzweig born around 1890-1892, using FamilySearch as my tool as it allows for liberal use of wild card searching and, unlike ancestry.com or other sites, reveals the names of the parents in the search results. I still did not see any Abrahams or Abes, but in scanning the results, I noticed a child named David who was born to Gadaly and Ghitel Saak Rosentveig. Before receiving the Romanian records for Gustave and Gussie I might not have recognized that these were their Yiddish names: Ghidale Rosentvaig and Ghitla Zacu on their marriage records from Romania. I knew that this could not be a coincidence, that this baby had to be their son, born September 5, 1891. Since I still have not found Abraham on the birth index, I cannot be sure whether David was born before or after Abraham. What I did realize was that David must have been named for my great-great-grandfather, David Rosentvaig, who had been alive in 1884 when Gustave married Gussie in Iasi but who must have died sometime before the birth of this new David.

I knew that this could not be a coincidence, that this baby had to be their son, born September 5, 1891. Since I still have not found Abraham on the birth index, I cannot be sure whether David was born before or after Abraham. What I did realize was that David must have been named for my great-great-grandfather, David Rosentvaig, who had been alive in 1884 when Gustave married Gussie in Iasi but who must have died sometime before the birth of this new David.

But where was the new David in 1900, only nine years later? Since he was not listed on the 1900 census, I assumed the worst, as I have gotten accustomed to doing, and checked the death index. Sure enough a one year child named David Rosenzweig had died on December 25, 1892. Although I have not yet seen the death certificate for this child, I have to assume that this was Gustave and Gussie’s son David. My great-great-grandfather’s namesake had died before his second birthday.

I have expressed in an earlier post my thoughts and feelings about the impact the deaths of babies and children must have had on their parents and their siblings. The numbers are staggering. On the 1900 census Gussie Rosenzweig reported that she had had thirteen children, only eight of whom were then living (Rachel was not yet born). In 1910, she reported eighteen births and only nine living children. Had she had five more infants die between 1900 and 1910? My great-grandmother Bessie Brotman reported in 1900 that she had given birth to nine children, only four of whom were living (Sam was not yet born). We also know that Hyman Mintz died within a month of birth and Max Coopersmith within a day of birth.

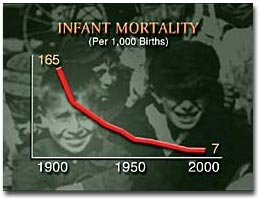

These infant deaths were not at all unusual for that time period. According to a PBS website for a program called The First Measured Century, “[p]rior to 1900, infant mortality rates of two and three hundred [per one thousand births] obtained throughout the world. The infant mortality rate would fluctuate sharply according to the weather, the harvest, war, and epidemic disease. In severe times, a majority of infants would die within one year. In good times, perhaps two hundred per thousand would die. So great was the pre-modern loss of children’s lives that anthropologists claim to have found groups that [did] not name children until they have survived a year.”

This same source reports that most of these deaths were caused by poor infant nutrition, disease and poor sanitary conditions. In the early 20th century substantial efforts were made to deal with these causes of infant and other deaths. “Central heating meant that infants were no longer exposed to icy drafts for hours. Clean drinking water eliminated a common path of infection. More food meant healthier infants and mothers. Better hygiene eliminated another path of infection. Cheaper clothing meant better clothing on infants. More babies were born in hospitals, which were suddenly being cleaned up as the infectious nature of dirt became clear. Later in the century, antibiotics and vaccinations join the battle.” The infant mortality rate began to decline, and today it is well under ten deaths per thousand within the first year of life in the United States.

But what impact did this high death rate for babies have on their parents? There have been many books written by sociologists, social historians and psychologists on the history of society’s view and treatment of children. According to this research, until the 18th century, children were not valued highly by parents, perhaps in part because of the high infant mortality rate. The likelihood of losing a child was so great that it made it difficult for parents to become too attached. In Europe often parents did not even attend the funerals of their children and even wealthy parents had their children buried as paupers. See, e.g., Viviana A. Rotman Zelizer, Pricing the Priceless Child: The Changing Social Value of Children (1994); Linda A. Pollock, Forgotten Children: Parent-Child Relations from 1500 to 1900 (1984). Both authors also observe that the attitude towards children changed during the 18th and 19th centuries as people began to be more concerned about their children’s growth and development and families started to become more child-oriented and affectionate. This change in attitudes contributed to the increased efforts to reduce infant mortality.

It’s so difficult for me to imagine that these parents were indifferent or unaffected by the deaths of so many of their babies. I know I live in another era, an era when parenting has become not just a part of life, but in some ways an obsession. I plead guilty to being a helicopter parent, to being probably too involved in my children’s lives as they were growing up. We live in a time of thousands of books on parenting, dealing with every issue imaginable. There are experts to help you before a baby is born and experts to help you deal with every imaginable childrearing issue that can arise after they are born: doulas, lactation consultants, sleep consultants, life coaches, tutors, college admissions consultants, and probably some I don’t even know about. So many of us center our lives on our children. Losing a child is often said to be the worst thing anyone can experience.

Could it really have been so different back then? Were children really seen as disposable and replaceable? Is that why people had so many children—in order to ensure that at least some would survive to adulthood? Or was it simply the absence of effective birth control, not the desire for so many children, that led to these huge families? Did those huge families make it easier to accept the loss of so many babies? Were even those who survived devalued and distanced as a defense mechanism against their possible death? It seems unlikely they were as doted upon and cherished as children of today, given both the cultural attitudes and the economic and environmental conditions of the time.

Maybe that made those children stronger and more self-reliant, less indulged and less entitled. But it also had to have left its scars. Maybe it is why so many of them did not want to talk about their families, their childhoods, their feelings.

You bring up a lot of good points here. I definitely agree with you that they MUST have cared for their children, at least most of them. But maybe I just can’t imagine the world any other way because I’ve only known the modern approach to parenting. (Or maybe I don’t want to!) In any case, it’s good to remember those high mortality rates, especially thinking in the broader context of how infant and mother mortality affected the emotional well being of families.

LikeLike

Thanks for your thoughts. It just boggles my mind to think of bearing a child for 9 months and then losing it. And then getting pregnant again and taking the risk that it would happen again…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have an ancestor for whom I found 6 stillborn birth records. They had children who survived as well, but that amount is unfathomable to me.

LikeLike

Thank goodness conditions have changed….

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amy, this is a great post. I put a link to it on my response to your comment on my post from yesterday. It had to be so difficult.

LikeLike

Thank you! It is unimaginable, isn’t it? I just can’t fathom it.

LikeLike

Thanks, Stephen. It is heartbreaking. And I know what the studies say, but I cannot imagine that any parent could just watch a child die and not be devastated. They just may not have expressed it the way we would today.

LikeLike

I loved this post Amy, the life that children led in the past has always interested me, and it’s so sad that many passed away whilst still in infancy.

Imagine not naming your child in fear that that they will die.

That concept is simply Heartbreaking!

LikeLike

Pingback: Joseph Rosenzweig: Update « Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Another Sad Story: Harry Rosenzweig « Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: The Rosenzweig Brothers: A Family Portrait « Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Document Updates on David and Jack Rosenzweig « Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Women are Difficult…to Find and Track, Part I: Lillian Rosenzweig « Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: My Grandfather’s Cousin Rebecca: Another Life Cut Short « Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Children Losing Parents: The Family of Leopold Nusbaum « Brotmanblog: A Family Journey