As noted in my last post, the population of Jews in Romania has declined precipitously over the last one hundred years as a result of emigration before World War I and thereafter and also as a result of the murder of about 300,000 of them during the Holocaust. From a peak of 800,000 after World I, there are now just a few thousand Jews living in Romania today. What is it like in Romania today, and, more specifically, what is it like to be a Jew living in Romania today? What legacy is there in Romania from the once substantial Jewish community, and what do current residents know or remember of the Jewish communities and of the Fusgeyer movement that led many of those Jewish residents out of Romania? Beyond the cold, hard statistical facts, what is left of Jewish Romania?

I have consulted only two sources of information to answer these questions, so my views are based on limited information and possibly inaccurate. But those two sources left somewhat different impressions, so perhaps the truth lies somewhere in between. Jill Culiner’s book, Finding Home, paints a rather gray and dismal picture of life in Romania in general and specifically of the Jewish legacy there. Stuart Tower, author of The Wayfarers, has a more positive impression of Romania today and of its people as seen in the photographs he took first in the 1980s and then in 2005 and also from what he shared with me by email. Culiner and Tower visited different cities and towns for the most part, but there was some overlap; both visited Barlad and Sinaia within a few years of each other. Both ultimately paint a picture of a country that once had many thriving Jewish communities but that now has virtually no Jewish communities and few residents who remember the communities that once were there.

Tower based his book around the town of Barlad; it is where the three Americans, grandfather, father and son, go to learn about their ancestral roots and meet the rabbi there who tells them the story of the Barlad Fusgeyers. Tower’s story is fictional, and he told me that he’d never actually met a rabbi in Barlad, but both Culiner’s book and Tower’s book talk about a very small Jewish community continuing to exist in that city and the beautiful synagogue that still stands there. In Tower’s novel, the rabbi describes a community of thirty people who still keep kosher and observe shabbat, but who have trouble forming a regular minyan. The elderly rabbi’s children have all moved away, and he knows that he will be the last rabbi in Barlad (spelled Birlad in the novel).

Culiner started her Romanian travels in Adjud, where she got off the train and began her Fusgeyer-inspired walk. Her description of Adjud is disheartening:

Here, fields lie flat under a grueling sun, and cars, trucks and buses roar with giddy impunity over pot-holed, uneven main roads. Under thirsty-looking trees outside the station, lining the street are unlovely lean-tos, modern bars and patios. All claim to be discos, all pump loud American music into the hot air.

Culiner, p, 35.

Culiner also said that “there were no buildings left from the pre-Communist era and certainly nothing of beauty.” (Culiner, p. 35) Her encounters with the local people are no more heart-warming. No one could tell her where there was a hotel or room to stay in, and she described the people she saw as “exhausted..expressionless, resigned.” Culiner, p.36. No one in town remembered that there ever was a Jewish community there or a synagogue, although there had been a community of about a thousand Jews there in 1900. The man who showed her where the non-Jewish cemetery was located demanded an exorbitant fee for his troubles. By the end of this first chapter, I was already feeling rather depressed about her experience and about life in Romania.

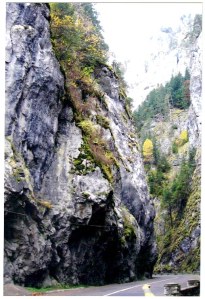

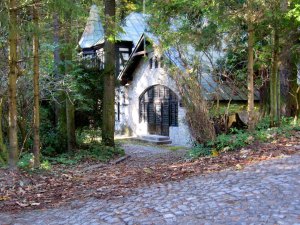

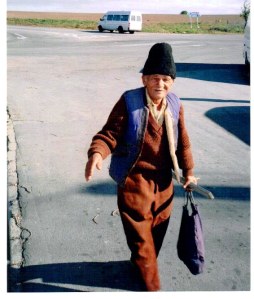

In contrast, here are some of Tower’s photos of the Romanian countryside that left me with a different impression. Thank you to Stuart Tower for giving me permission to post these:

Culiner’s experience at her second stop, Podu Turcului, was not any better. The townspeople warned her that her plans to walk through Romania were dangerous and that she would be better off visiting more modern cities elsewhere. There were no Jews left in this town, and no one there remembered there ever being a synagogue, although there was a Jewish cemetery. Only one man acknowledged that there once was a Jewish community there, a workman who had been curious about the Jews while in school and had learned where the Jewish residents had once lived in town, now just a neighborhood of faceless housing from the Communist era. This man told Culiner that he had been unable to learn more about the Jewish community in his town because discussing such matters was prohibited during the Communist era.

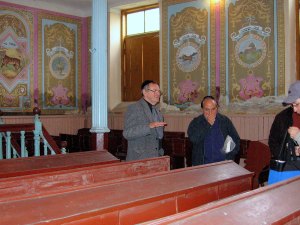

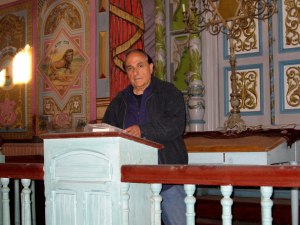

Culiner and her companion next arrived in Barlad, a city of 79,000 people, the city where Tower’s characters stayed and learned about the Fusgeyers and were in awe of the beautiful synagogue. Culiner is less enthusiastic. Her first impression of the city is its “potholed, deteriorated sidewalks” and the “[r]are trees [that] gasp out their life in the dense cloud of exhaust fumes, providing little shelter from the pitiless sun.” (Culiner, p. 55) Culiner once again encountered skepticism about her plans and ignorance about the Jewish history of the city. She was particularly disappointed that in this city where the Fusgeyer movement began, no one seemed to remember anything about them. Even she, however, was impressed with the synagogue, to an extent:

Despite its rather austere, unassuming exterior, the synagogue is magnificent. Dating from 1788, the walls and ceilings are decorated with paintings of birds, flowers, leaves and imagined scenes of Jerusalem. Yet, despite its beauty, there is a strange feeling of loss, the aura of a building struggling to exist in a world that has little place for it. It has become a relic.

Culiner, p. 58.

Although Tower also described a dying Jewish community in his novel, there was still some life, some people who cared in Barlad. Culiner saw the glass as half-empty whereas Tower saw it as half-full. Here are some pictures of the Barlad synagogue and some other towns visited by Tower that show a far less dismal impression of in Romania. All photos courtesy of Stuart Tower.

Culiner’s experiences in the towns and cities she visited after Barlad were not much different from her first three stops: ignorance and indifference to the history of the Jewish communities in those towns, ugly scenery, and disappointment. She did meet some friendly and helpful people along the way, including some who were Jewish or were descended from Jews, but for the most part she found most Romanians at best ignorant and at worst rude and even hostile.

In Focsani, no one seemed to be able to help her find the synagogue, sending her on a wild goose chase only to find it right near her hotel. On the other hand, Focsani had a fairly active Jewish community (relatively speaking), as the synagogue regularly drew about twenty people for shabbat services and more on major holidays. Culiner was bewildered by the fact that the non-Jewish residents did not even know where the synagogue was located despite its central location.

In Kuku, Culiner met a friendly, helpful woman who likely lived in a building that was once the hostel where the Fusgeyers stayed while traveling through that town, but that woman also knew nothing about where the Jewish community had gone or about the Fusgeyers. In Ramnicu Sarat, Culiner spent time with a woman whose mother was Jewish and who remembered the days of an active and close Jewish community. The woman told Culiner that the Communists had demolished the synagogue that had once stood in the town. She also talked about being unable to be openly Jewish during the Communist era.

Similarly, in Buzau she talked to a Jewish man who refused to take her inside the synagogue because he was ashamed of its condition; there were not enough Jews left in the town to make a minyan and not enough money to maintain the building. This man told her that “the greatest threat is that all will be forgotten.” Culiner, p.122. In Campina, another Jewish man told her, “The Jews will die out. We will go to the cemetery. And no one will replace us.” Culiner, p. 144.

Only in Sinaia did Culiner find anything of beauty in the countryside, but again not without some negative observations. She wrote: “The scenery is a slice out of a romantic painting and Watteau would have delighted in the mossy banks, the majestic spread of trees, although he might have taken artistic liberty, ignored the discarded shoes and packaging stuffed into vegetation, the tattered plastic and ripped shreds of fabric caught on branches in the river.” Culiner, p. 146. Tower’s photographs of Sinaia reveal all the beauty without the observations of garbage mentioned by Culiner.

Before I read Culiner’s book, I had been giving serious thought to an eventual trip to Romania, in particular to Iasi. After reading her book, I put that thought on the far back burner. Her book left me with a vision of an ugly country filled with ugly people who hated Jews. After looking at Tower’s photos and corresponding with him about his travels in Romania, I am reconsidering my decision to put a visit there on the back burner. Just as I would like to visit Galicia to honor my Brotman family’s past, I would like to visit Iasi—to see where my grandfather was born and spent his first sixteen years, to honor his past and the lives of his family—-the Rosenzweigs and the Goldschlagers. I have no illusions about what I will find there. I know not to expect a lively Jewish community or even any Jewish community. It’s all about walking where they walked and remembering their travails and their courage. Maybe the scenery is not as idyllic as in some of Tower’s photos. Maybe the people are not as colorful and friendly as they seem in his photos. But that, after all, is not the point, is it?

Culiner did not visit Iasi, our ancestral town in Romania, on her trip, but Tower did, and I thought I would end this post by posting his pictures of Iasi and some of its people as well as those taken by my Romanian researcher Marius Chelcu. Maybe someday I will get to be there in person and walk down St Andrew’s Street where my grandfather was born and pay tribute.

If we don’t, who will? Will we allow the story of the Fusgeyers and of the Jews of Romania to be forgotten for all time? That, in some ways, is the message of both Tower’s book and Culiner’s book: we need to learn and retell the story of our ancestors so that those stories and those people will not be forgotten.

Stuart Tower’s photos of Iasi

Marius Chelcu’s photos of Iasi:

Interesting opinion…

LikeLike

Thanks

LikeLike

My cousin Alan Tobias and I (Martin Tobias) visited Romania in 2001 three months before 9/11

and traveled all over the country, enjoying the scenery and history. We went there to trace our “Tobias” family roots which we knew came from Iasi…but had very little information on where they

lived , except for one of our uncles mentioning the “little red bridge area. We went to the”Great

Synagogue” which wasn’t that great and spoke to a few elderly members telling how most of

the younger people left for Israel or USA and very few are left. I am an artist and on returning to

Riverside CA where I live I painted a series of work on our travels…My website is tobiasstudio.com

and wish you can see the paintings and drawings I produced. I had an exhibition in our Riverside

Art Museum in 2002 and also exhibited my work at the Romanian Embassy in Washington DC.

I am interested in your writings and would love to hear from you…thank you for retaking me back to my heritage, Sicerely, Martin Tobias

LikeLike

Thank you, Martin. I will look at your art and be in touch. I’d definitely like to hear about your travels. I hope to get to Iasi some day soon.

LikeLike