The youngest child of Reuben and Sallie Cohen was Simon L. B. Cohen. He was born on February 25, 1898, in Philadelphia, and spent his childhood in Philadelphia and Cape May like his siblings.

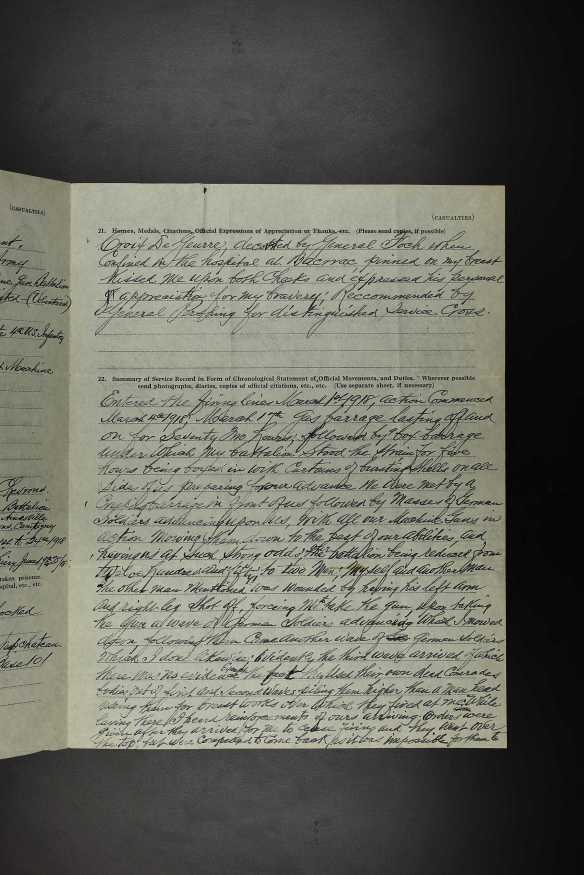

When he was nineteen years old, he voluntarily enlisted in the US Army as a private in the infantry. According to a questionnaire he completed for the American Jewish Committee, he had been a professional boxer before enlisting. While in the service, Simon was promoted to sergeant and served in the machine gun battalion. He was wounded in March, 1918, while fighting with his battalion in France. In the questionnaire for the American Jewish Committee, he provided this detailed description of the battle in his own hand.

I will try to transcribe it as best I can, preserving the original spelling and punctuation as well as Simon’s expressive language:

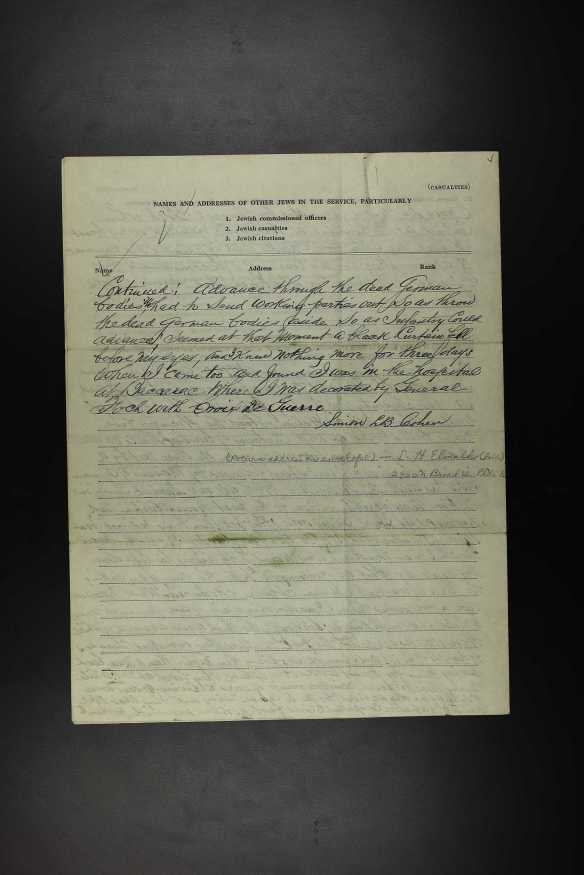

Entered the firing lines March 1, 1918, action commenced March 4, 1918; March 17 gas barrage lasting seventy-two hours, followed by a box barrage under my battalion stood the strain for five hours being boxed in by curtains of bursting shells on all sides of us preparing for an advance. We were met by a creeping barrage in front of us followed by masses of German soldiers advancing towards us, with all of our machine guns in action mowing them down to the best of our abilities, and having us at such strong odds, our battalion being reduced from twelve hundred and fifty to two men; myself and another man. The other man mentioned was wounded by having his left arm and right leg shot off, forcing me to take the gun, upon taking the gun, a wave of German soldiers advanced, which I mowed down, following them came another wave of German soldiers which I done likewise; Evidently the third wave arrived of which there was no evidence except the fact they used their own dead comrades bodies out of first and second waves piling them higher than a man head using them for breast works over which they fired at me. While laying there I heard reinforcements of ours arriving. Orders were given after they arrived for me to cease firing, and they went over the top but were compelled to come back, as it was impossible for them to advance through the dead German bodies, had to send working parties out so as throw the dead German bodies aside, So as infantry could advance. Seemed at that moment a black curtain fell before my eyes, and knew nothing more for three days. When I come too and found I was in the hospital at Baccarac where I was decorated by General Foch with Croix de Guerre.

I have read plenty of literature about the horrors of war, from All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Remarque to The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien, among many other fictional and factual accounts of battles and the horrible things that young people experience and see when serving as soldiers. But I have never read one by someone related to me, someone whose family I had been researching and writing about for days and weeks before reading this account. This was a boy, the baby of his family, one of the few children who had survived to be a young man out of the seventeen children born to his parents. He grew up with a successful father and lived a life of relative luxury and comfort, spending summers at the seaside in Cape May. He had many older siblings and his parents who must have treasured him as one of the few who had survived.

And then he volunteered to help his country and was exposed to this: Being one of two of 1250 young men to survive being mowed down by other young men, seeing his friends and comrades die before him. Killing probably many, many other young men who happened to be German by “mowing them down” with a machine gun. Watching them use the bodies of their own dead comrades as protection on the battlefield and then watching his own countrymen throw those bodies aside so that they could advance against those other young men. How could a nineteen year old boy like Simon watch and experience these things and not be scarred forever? What does something like that do to someone?

Simon’s story did not end there. As he mentioned in his account, he was awarded the Croix de Guerre by General Ferdinand Foch, Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Forces, while in the hospital recovering from his injuries. As he described that occasion, he was decorated by General Foch, who pinned the medal on his breast, “kissed [him] on both cheeks and expressed his appreciation for [Simon’s] bravery.” Simon was also recommended by General Pershing for a Distinguished Service Cross.

General Ferdinand Foch, Commander in Chief, Allied Forces, World War I

Do these medals and honors make up for the pain and suffering and mental distress that he endured? Simon recognized that the war had had a psychological effect on him. On the questionnaire, Simon mentioned that he suffered from shell shock or what we today call post-traumatic stress syndrome. He was rightfully recognized for his service and his sacrifices, but for me, that hardly makes up for the price he paid while engaged in that service.

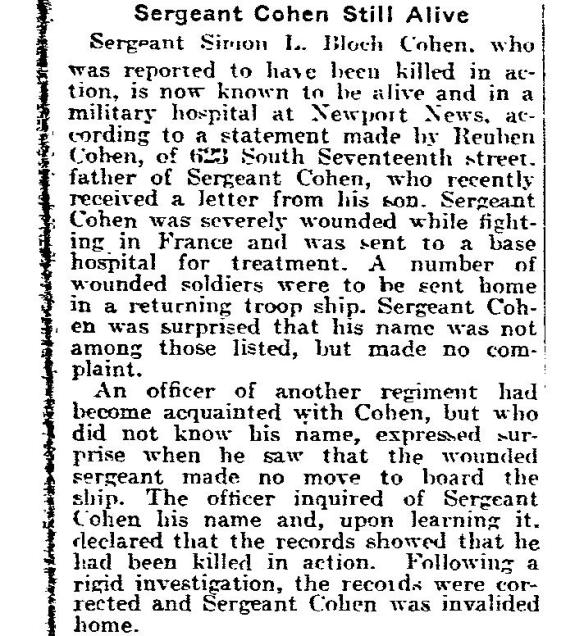

To make matters even worse, his family back home was subjected to extraordinary emotional distress. As this news article from the Philadelphia Inquirer reports, Simon had been mistakenly reported as killed in action while he was actually recuperating in France. Only after an officer was surprised to see that Simon was not being sent back home to recover did he and Simon learn that Simon had been thought to be dead. (“239 Phila. Soldiers Killed during War Two Soldiers Reported Dead Yesterday with 10 Wounded,” Thursday, September 12, 1918 Paper: Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA) Volume: 179 Issue: 74 Page: 14)

Imagine thinking that your youngest son had been killed. Imagine that after already losing ten of your children you were told that another had died. Then imagine the shock, the relief, the joy, maybe the anger you would feel when told that he was in fact alive.

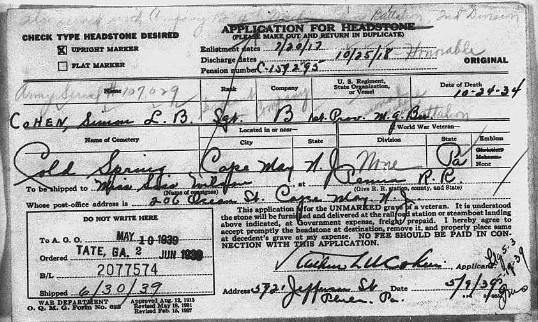

So Simon did come home, and by 1920 he was back living with his parents and some of his siblings in Cape May. The 1920 census reports that he had no occupation. However, by 1930 he was married, living in Cape May, and working as a clerk for some company I cannot decipher on the census report. He and his wife Myrtle had only been married for one year. Simon’s father Reuben, Sr., had died just four years before in 1926. His mother Sallie died in 1930. Four years later, Simon himself died on October 24, 1934. He was only 36 years old. I plan to order his death certificate from the State of New Jersey, but thus far I have not found any explanation of his cause of death. I won’t speculate, though I have some thoughts.

Simon was buried in Cold Spring Presbyterian Cemetery near Cape May. Five years after his death, Simon’s older brother Arthur L.W. Cohen, Sr., applied for a military headstone to mark his brother’s grave. His short life must be remembered not only because he served his country proudly and bravely, but also because for me it will always be a reminder of the horrible things we do to these brave and proud young people when we send them off to war.

What’s the questionnaire for the American Jewish Committee all about? Why? What else is included?

LikeLike

Here is how ancestry.com describes the database of these questionnaires: “These surveys were sent out by the American Jewish Committee (AJC) Office of Jewish War Records as part of an effort to document the service of Jews in the American armed forces. The AJC felt it important to both record and publicize Jewish service—in particular casualties and decorated soldiers—in the war and sent out 16,000 questionnaires soliciting information on soldiers they believed to be Jewish. The questionnaires came in 2- and 4-page versions, though both forms asked for the same information. The longer forms were typically sent to officers, casualties, or next of kin.” Simon received the four page questionnaire, and it is included in the database. I only reproduced two of the four pages here.

There is also a letter in Simon’s file dated April 6, 1920, sending three questionnaires to Reuben Cohen, asking about the service of his three sons in World War I. I only found Simon’s in the database. I assume the other two brothers were Lewis and Arthur.

LikeLike

Very moving. Warfare then was so much different to today. I never fail to get choked up thinking about how men like Simon who were not men who had ever thought of a military career, got caught up in all of it, witnessing such horrors that people shouldn’t have to see. Losing friends and relatives and coming home with awful memories that would have never left them. Also for his family – the anguish of hearing of him being killed in action and the sheer joy and relief to know he was coming home. What a rollercoaster of emotions.

LikeLike

I wrote this up last night before going to sleep. Bad move—I was haunted by visions of Simon in that battle and could not fall asleep. If just reading about his experience had that effect on me, the effect on him as the person who actually experienced it must have been devastating. But the world has not learned from “the war to end all wars,” and we continue to subject people to the violence and cruelty of war.

LikeLike

What a harrowing, emotionally wrenching story. I can’t get Simon’s words out of my head.

LikeLike

Neither can I. The images are just so clear and so horrifying.

LikeLike

Sharing on Twitter and the Facebook page for my other blog.

LikeLike

Thank you. I was trying to figure out how to get more readers to see this one. It’s an important one for me for lots of reasons. I appreciate your help!

LikeLike

Are you on Twitter?

LikeLike

I think I have a Twitter account, but have never figured out how to use it. Any suggestions? Thanks!

LikeLike

OK, I figured out how to connect my posts to my Twitter account. Now I have to figure out how to use Twitter itself! Thanks for making the suggestion!

LikeLike

You can connect with family history/genealogy people on Twitter. It takes a little while to build a group of followers by following them, retweeting their stuff, favoriting, etc. But then you will end up with a community of the like-minded. I did this for the adoption blog my daughter and I have, and we have a great adoption twitter account, but we stopped blogging about adoption, at least for now! Don’t try for 1000s. Try for a few hundred who are devoted to family history and also some Jewish history sources, Ancestry, etc. I haven’t done this because I am so focused on my writing blog, but I do have a few followers and follow a few on that twitter account who are into genealogy. And a few for Kalamazoo.

LikeLike

OK, thanks! I just went to my account to see what I had there. NOT MUCH! I am now doing as you suggested. I am so used to Facebook that Twitter just feels…empty? But I will take your advice and check it out, Luanne!

LikeLike

I felt that way at first, too, but I quickly caught on to it, and there is an ease on there that you don’t have with Facebook. It does different things than Facebook does.

LikeLike

Well, this will test my ability to be a full fledged social media-ite!

LikeLike

I am working on my Twitter stuff, and I wondered how you found genealogy people. I can find all the commercial sites (ancestry, familytreedna, etc.), but aside from you, I don’t have anyone to follow who is doing family research. How did you find them?

Thanks!

LikeLike

In the search bar put #genealogy and then look through what comes up (in reverse chronological order) and go into different accounts and see if you think that is a person you want to follow. I also tried #jewishgenealogy and accounts came up, too, although there are not as many (very quickly I was back to July of last year). Try #familyhistory

LikeLike

Thanks! I will do that. I just retweeted your post—-so I am learning slowly!

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike

If you do it, look for me under Luanne Castle :).

LikeLike

I had heard stories of my great-uncle Simon over the years from my father and aunt, and had read the story of this battle written in his own hand as a letter home to family in Cape May, but I had never seen this particular account.

It’s truly shocking, and I cannot imagine what it must have done to a soldier’s mind – or even what it still does today.

I never met him, as he had died long before I was born, but by the stories recounted by both my aunt and my father, who apparently adored him, he appeared happy for the rest of his life.

LikeLike

Thanks, Jim, for your thoughts and your insights. Obviously, your grandfather felt strongly that his brother’s service should be recognized on his gravestone. And I found yesterday a description of Reuben that I will try and post in the next day or so that mentioned that Reuben was most proud of his son Simon’s service in World War I. It’s an awful story because of what he experienced, and it’s truly amazing that he was able to find happiness after the war. Do you know what his cause of death was? Any chance you have a copy of his death certificate? I can order it from NJ, but it will take a few months before I will get it from them.

Thanks again!

LikeLike

Pingback: Number Thirteen, the Caboose: Abraham Cohen 1866-1944 « Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Death Certificates: Answering Some Unanswered Questions « Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Passover 2015: The American Jewish Story « Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Cohen and Company Photograph: Is That My Grandfather? | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Measures of Valor: American Jewish Military Service in World War One – Part Two – Excursions in Jewish Military History and Jewish Genealogy