I thought I should outline my connection to the Nusbaums before I began writing about them. The chain between Amson Nusbaum and me is as follows, with the Nusbaum descendants all on the left side of each couple:

Amson Nusbaum—Voegele Welsch (my 4x-great-grandparents)

John (Josua) Nusbaum—Jeannette (Shamet) Dreyfuss (my 3x-great-grandparents)

Frances Nusbaum—-Bernard Seligman (my great-great-grandparents)

Eva May Seligman—-Emanuel Cohen (my great-grandparents)

John Nusbaum Cohen, Sr. — Eva Schoenthal (my grandparents)

John Nusbaum Cohen, Jr. —- Florence Goldschlager (my parents)

Amy Cohen (me)

(Although the Nusbaums spelled their name with two S’s in Germany as in NUSSBAUM, the family dropped the second S once they got to the US, just as the Seligmanns dropped the second N when they immigrated.)

So where do I start telling this Nusbaum story? I have already talked about my grandfather John Nusbaum Cohen’s life and his mother Eva Seligman Cohen’s life in telling the stories of the Cohens and the Seligmans. So I could start with my great-great-grandmother, Frances Nusbaum, who married Bernard Seligman. I’ve also written a little about her. But I prefer to start at the earliest point and move forward in time. Right now the earliest Nusbaum ancestors I have found date back to the 18th century with Amson Nusbaum and Voegele Welsch.

This is the first branch that I have been able to take back as far as my 4x-great-grandparents. Although I know very little about Amson Nusbaum and Voegele Welsch, I am hoping that I can learn more if I can obtain more records from Schopfloch. But for now, here is what I know.

Amson Meier Nusbaum was born around 1777 possibly in Schopfloch, a small town in the Ansbach region of Bavaria. He married Voegele Welsch, who was born March 7, 1782, somewhere in Germany. They were married around 1804, and they had eight children born between 1805 and 1819, all born in Schopfloch. Amson was a peddler.

Although I do not have much specific information about Amson and Voegele, I was interested in learning more about the town where they lived and raised their children in order to glean something about what their lives might have been like.

First, I read a little bit about Bavaria. I really know almost nothing about Germany’s history, but I do know that it was not a unified country until 1871. Before that, there were a number of separate duchys and kingdoms controlled by various aristocrats and noblemen, fighting over their borders for many hundreds of years. From the tenth century until the beginning of the nineteenth century, the land that we know as Germany was part of the Holy Roman Empire. The Thirty Years War from 1618 to 1648, which started as a conflict between Protestants and Catholics and grew to a much larger regional conflict, was perhaps the most destructive of the wars that occurred during this pre-unification era in the area we now call Germany.

Bavaria was one of those regions within what is now Germany. It is located in the southeastern part of the country, bordering the Czech Republic and Austria to the east and south. The official website for what is now the state of Bavaria within the Federated Republic of Germany said this about the history of Bavaria:

Bavaria is one of the oldest states in Europe. Its origins go back to the 6th century AD. In the Middle Ages, Bavaria (until the start of the 19th century Old Bavaria) was a powerful dukedom, first under the Guelphs and then under the Wittelsbachs. … Cities like Regensburg developed into cultural and economic centres of European rank. After the Thirty Years War, the Electorate of Bavaria played an important role in the political deliberations of the major powers. In the 19th century Bavaria became a constitutional monarchy and the scene of a great cultural blossoming and of political and social reforms.

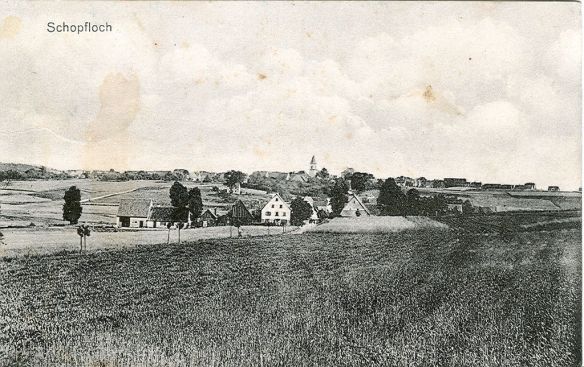

Schopfloch is a small town of three thousand people located near the western boundary of Bavaria. It is about sixty miles west of Nuremberg, about one hundred miles northwest of Munich, and about eighty miles northeast of Stuttgart.

According to the official town website, the earliest mention of the town dates from March 11, 1260, on a land deed witnessed by someone named Ulricis de Schopfloch. (Schopf loch apparently means “ crested hole” or “tuft hole,” and perhaps this is a reference to the fact that the town is located in a small valley). During the Thirty Years War, many Protestants moved from Salzburg to Schopfloch. They were primarily tradesman in the building trades—masons and bricklayers– and the town was known for its many families in the construction business.

The history of the Jews in Bavaria is, like the history of Jews in most countries in Europe, one of oppression, discrimination, unfair taxation, and frequent pogroms with occasional periods of greater tolerance and civil rights. There is evidence of Jews living in Bavaria as early as the 900s, and numerous towns and cities in Bavaria had Jewish communities by the 12th century. Jews were limited in their livelihoods in many locations; in many places, they were prohibited from most trades other than moneylending. Beginning in the 14th century and continuing through the 17th century, the Jews were subjected to widespread orders of expulsion and deportation from many Bavarian communities. A good summary of the history of Jews in Bavaria can be found here at H. Peter Sinclair’s “Chronology of the History of the Jews in Bavaria 906-1945,” .

As for Schopfloch specifically, the first Jews settled there in the fourteenth century. According to The Encyclopedia of Jewish Life Before and During the Holocaust: K-Sered (Shmuel Spector, Geoffrey Wigoder, eds., 2001, NYU Press), p.1151, Jews moved to Schopfloch after being expelled from the nearby town of Dinkelsbuehl. Another source suggests that Jews were welcomed to Schopfloch by rival nobles who took in Jews to increase their strength. Jews were able to do well, engaging in cattle trade in Schopfloch and in several communities near Schopfloch.

A Jewish cemetery was created around 1612 and served not only the Jewish residents of Schopfloch but also those of surrounding towns.

Jewish cemetery in Schopfloch

at http://www.alemannia-judaica.de/images/Images%20231/Schopfloch%20ETJK%202009014.jpg

A synagogue was built in 1679, and there was also a ritual bath and a school. According to the website “Destroyed German Synagogues and Communities” :

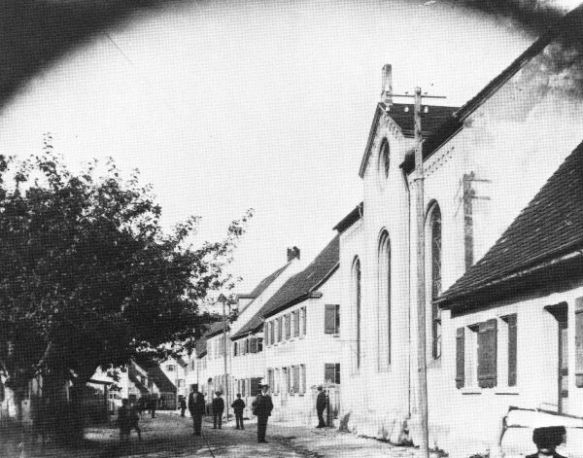

The Jews of Schopfloch established a synagogue in 1679 and enlarged it in 1712 and again in 1715. Rabbis served the community during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, and the village was home to a regional rabbinate during the years 1841 to 1872. In 1877, a new synagogue was built on the Judengasse, or “Jews’ alley” (later renamed Bahnhofstrasse).

According to the town website, the Jewish residents played an important role in the social history of the town, and the long history of co-existence between the Christians and Jews in Schopfloch made it less susceptible to anti-Semitism even in the Nazi period. Perhaps there were no pogroms or expulsion orders in Schopfloch. None were mentioned in H. Peter Sinclair’s “Chronology of the History of the Jews in Bavaria 906-1945,” cited above and found here.

Overall, it would seem that Schopfloch would have been a relatively comfortable place for Jews to live when my ancestors Amson and Voegele Nussbaum were having children between 1805 and 1819 and the years following when their children were growing up. Amson died June 7, 1836, and Voegele died October 2, 1842. From what I can find in immigration records, my three-times great grandfather John (Josua) Nusbaum emigrated in 1843, the year after his mother died. It appears that at least some of his siblings emigrated around the same time. What would have motivated them to leave once their parents had died if in fact conditions for Jews were relatively good in Schopfloch?

The Nussbaum family was growing up in an era of significant change in Bavaria and in Europe generally. Napoleon had risen to power in France as the 18th century ended, and the Holy Roman Empire crumbled. His armies invaded the lands in what is now Germany, and eventually he defeated the Austrian army and took over much of German land. His emancipation of the Jews in France in 1806 had an impact on those in Bavaria, and in 1813 Bavaria adopted the Jews Edict of 1813. Although Napoleon was defeated shortly after, the Jews Edict of 1813 remained the law in Bavaria.

The Jews Edict was a mixed blessing. As described by one source, “Jews now could acquire land and participate in trade but they were forced to adopt German surnames and to list the head of the household’s name and occupation as shown in the Matrikellisten (census) of 1817.” This registry (while a good thing for genealogy research), which may seem benign, had a negative impact on Jews because it forced many Jews to leave their homeland. Section 12 of the Edict provided that the number of Jewish families in any community could not increase. That meant that a child in a Jewish family could not establish his or her own family, but had to leave the community. Section 13 provided some exceptions, but they were quite restrictive. In addition, Section 14 prohibited the issuance of a marriage permit even if the marriage would not result in an overall increase in Jewish families unless the man could demonstrate that he was going to engage in a legal occupation other than being a peddler. http://www.rijo.homepage.t-online.de/pdf/EN_BY_JU_edikt_e.pdf

Thus, not all of Amson and Voegele’s children could stay in Schopfloch. To do so would have created eight new Jewish families in the town. Moreover, since Amson had been a peddler, chances are at least some of his sons had planned to engage in a similar trade. So they had to leave Schopfloch, and since the neighboring towns were under the same restrictions, they could not even settle nearby. They had to emigrate, and I am sure that America, a new country with a democratic form of government, must have been very appealing to these young people who were being denied the right to stay in the town where they were born.

The Jewish population in Schopfloch hit its peak in 1867 with 393 Jewish residents out of a total population of 1,788. Although a new synagogue was built in 1877, by 1880 the Jewish population had dropped to 147 people. It continued to drop so that by the early 1930s there were fewer than forty Jews in the town. Nevertheless, the synagogue was renovated in 1932, and there was a large celebration rededicating the synagogue, attended by many Jews and non-Jews, including members of the Christian clergy, the mayor, and other town officials and residents. One pastor spoke about the good relations between the Christian and Jewish residents of Schopfloch.

Schopfloch synagogue 1910 Source: Wallersteiner Kalendar, 1983 found at http://www.alemannia-judaica.de/schopfloch_synagoge.htm

Tragically, just five years later on November 9, 1938, the Night of Broken Glass, or Kristallnacht, this newly renovated synagogue was destroyed by fire. As described on the “Destroyed German Synagogues and Communities” website:

In 1938, in the wake of virulent anti-Jewish incitement, Schopfloch’s mayor advised the Jews to leave. All of them did so within months, and the synagogue was eventually sold (its ritual objects were transferred to Munich). Schopfloch’s last Jews left in October 1938. Although the synagogue was set on fire on Pogrom Night, the blaze was extinguished by the fire brigade. The building’s interior was completely destroyed, as were the ritual objects in Munich. Three Schopfloch Jews emigrated; the others relocated within Germany. Forty-eight perished in the Shoah. The synagogue building was demolished in 1939.

The cemetery, however, still exists, and a woman named Angelika Brosig began a project to restore the cemetery and to record all the names of those buried in the cemetery. Sadly, Ms. Brosig died in 2013, and not all of the headstones have yet been translated and recorded, but the work is supposed to be continuing by others. Thus far, I have not found any Nussbaums on the list, but I have to believe that my four-times great-grandparents Amson and Voegele are buried there.

Although Schopfloch is and was a small town without any particular historical significance of its own, it has been recognized for an interesting reason. The Jews of Schopfloch developed a dialect of their own to be used in the course of cattle trade as a way of communicating without being understood. It was a dialect combining Hebrew terms with German, and eventually it was used not only by the Jewish residents of Schopfloch but also by the non-Jewish residents. In fact, the dialect, called Lachoudish, a shortened version of Lachon Kodesh, or “holy language” in Hebrew, continued to be used by the residents of Schopfloch long after all the Jews left the town in the 1930s. The New York Times published an article about this secret language on February 10, 1984, giving some examples of the use of Hebrew terms in the dialect:

Lachoudisch is replete with words that bespeak the Jews’ wary relationship to Christian authority. The word for ”church” in Lachoudisch is ”tum” – from the Hebrew word for ”religiously unclean.” The word ”police” is ”sinem”- from the Hebrew for ”hated.” A priest is a ”gallach” or, in Hebrew, ”one who shaves.”

(James M. Markham, “Dialect of Lost Jews Lingers in a Bavarian Town,” The New York Times (February 10, 1984) found at http://www.nytimes.com/1984/02/10/world/dialect-of-lost-jews-lingers-in-a-bavarian-town.html The article also provides historical and current information about the town.)

This website provides further examples of Hebrew terms used in Lachoudish. http://www.medine-schopfloch.de/Lachoudisch/lachoudisch.html Although Lachoudish is disappearing as there are fewer Schopfloch residents who remember it, there has been some effort to remember and revive the dialect. This video, which unfortunately for me is in German, is about Lachoudish and also provides some images of Schopfloch today. If anyone wishes to translate this for me, please let me know.

Fascinating! I have Prussian ancestors so I am familiar with the “lost language” obstacle. I hope you are able to find someone to translate for you!

LikeLike

Thank you! So do I!

LikeLike

Very interesting !!

LikeLike

Thanks! Too bad we don’t have a secret language…

LikeLike

So much interesting information here. It’s unimaginable, and so sad, that our children would be forbidden to start families near us. I’m amazed at all the “creative” forms persecution can take.

LikeLike

Yes, it is unimaginable. Of course, today most of our kids choose to move out of town, but at least it’s their choice.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post with a lot of interesting information!

LikeLike

Thank you! I found this fascinating to research. I am always learning something new, something I never expected to find.

LikeLike

Pingback: Follow up on Schopfloch: Who Replaced My 4x-Great-Grandfather Amson Nussbaum « Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Passover 2015: The American Jewish Story « Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

I found out about Schopfloch and lachoudish when we were on post with the Israeli Embassy in Germany (This was in the 80’s)

I took a train down, met the mayor and a number of important citizens.One of these had compiled a dictionary of the “secret language” and was holding classes for members of the young generation to teach it

I subsequently wrote an article which appeared in the Hadassah Newsletter (now Hadassah Magazine).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading and commenting, Lili. I’d love to see your article. Is it available online? Or could you send me a copy? Thanks!

LikeLike

Pingback: Something I Never Expected to See | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Schopfloch: A Lesson in Gravestone Symbols | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Amy, so happy to see the Leo Baeck Institute share this! Very informative!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really? I had no idea—where did you see the link? Thank you!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Their Facebook page. It was posted yesterday but I just saw it today. You’re very welcome! It’s well deserved!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I will have to go check it out—thank you!!

LikeLike

I came across your post when I looked for the meaning of Schopfloch. I am familiar with the town…not sure if we ever stopped there, or just drove through/past.

I watched the video. The title basically translates to ‘on Saturdays (Sabbath Day), the mayor is off’. The mayor is one of the principal interviewees. The older person is the son of Jewish parents who emigrated from Schopfloch to the US. He studies Lachoudisch, as it was the language spoken at home. I would have translated it for you word for word, but much of what is talked about is the history of Jewish people in Schopfloch and the area in general, which you already recounted throughout your post. The people recount their experience with the language and that they recall a lot of the words. The group playing cards uses it exclusively when they play. They also speak about how they feel about their secret language.

I was surprised when the word ‘malochen’ came up. This word has probably made its way around to a lot of places in Germany. It means working, but more so working hard, to almost exhaustion, slaving. I recall us using this word among the young folks in Bernhausen, near Stuttgart in Schwaben/Swabia as I was growing up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for watching the video and giving me a synopsis of what is being said. I really appreciate it!

LikeLike