My last post ended with the tragic deaths in November 1901 of my cousin Bertha Seligmann and her husband Bernhard Gross; they had died from carbon monoxide poisoning while in their own home in Bingen, Germany. Bertha was the first cousin of my great-great-grandfather, Bernard Seligmann. We are both descendants of my 4x-great-grandfather, Jacob Seligmann.

Much of what I have learned about the life of Bertha and Bernhard came from the memoir written by their daughter Mathilde, Die Alte und Die Neue Welt (1951). As I mentioned in the last two posts, Mathilde lived a hundred years, from 1869 until 1969, and resided on two continents during her remarkable life, first in Germany, then in the United States. This post will focus on Mathilde and her family and descendants and their lives after 1901.

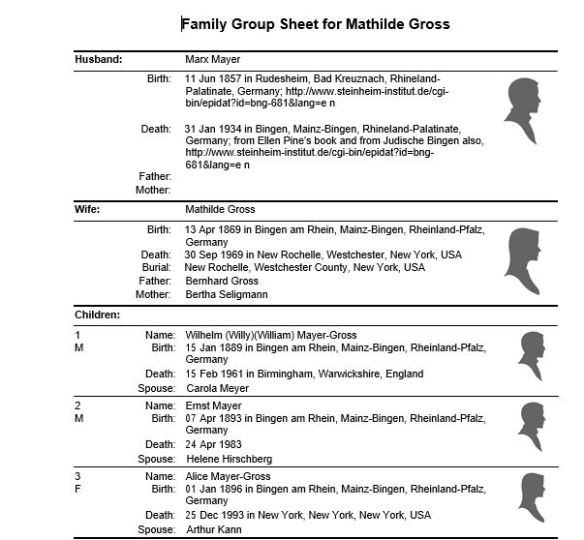

Mathilde was the oldest of Bertha and Bernhard’s five children. [1] As stated above, she was born in 1869, and she married Marx Mayer in 1888. They had three children: Wilhelm (known as Willy) Mayer-Gross (1889), Ernst (1893), and Alice (1896). All three would live interesting lives.

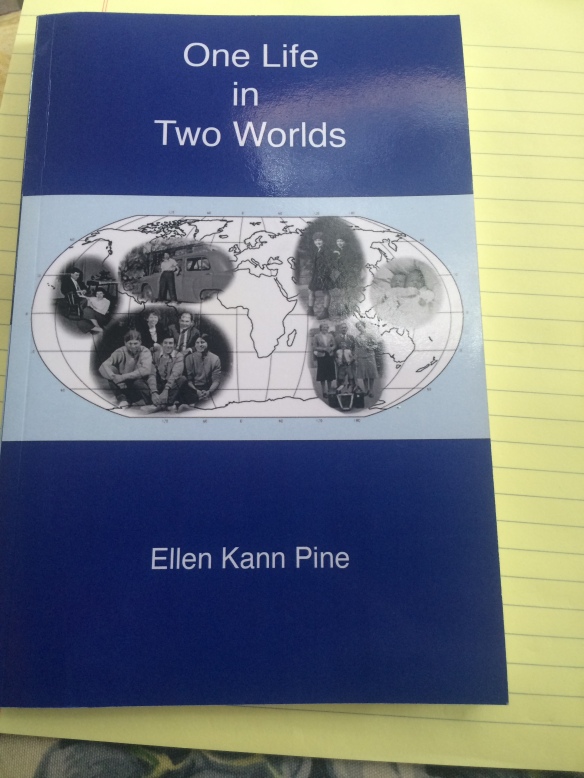

Although Alice Mayer was the youngest of the children of Mathilde Gross and Marx Mayer, I am going to write about her first because it is her daughter, Ellen Kann Pine, whose book One Life in Two Worlds (self-published, 2009) provided me with insights into the life of the Mayer family in the 1920s and 1930s. All the facts related in this post came from Ellen Kann Pine’s memoir, except where noted.

According to Ellen’s memoir, her mother Alice Mayer married Arthur Kann, whose father was in the wholesale grain business in the Bingen area. Their twin daughters Ellen and Hannelore were born in 1921 in Bingen. Ellen’s description of her childhood growing up in Bingen sounds quite idyllic. She describes Bingen in those days as the largest town in the area with about 10,000 residents.

Her family shared a house with her father’s brother Julius Kann and his wife. The house was on the edge of town and was located across the street from Ellen’s grandparents, Mathilde (Gross) and Marx Mayer. She saw her grandparents every day. Ellen wrote:

No day passed without a visit from one or both of them. Our Grandfather (Opapa) was usually the first to come. He always brought each of us a piece of chocolate wrapped in foil in the shape of a coin. …Our Grandmother (Omama) usually visited in the afternoon and she was always interested in what we had been doing and asked us to tell her.

Pine, p. 7.

Their grandmother Mathilde would take them for walks in the neighborhood every day. In addition, numerous aunts, uncles, and cousins lived nearby. The town was small enough that most people knew each other, and the Kann home had a big enough yard for the children to play.

In 1927, the twins started school at the local Volksschule where both Jewish and Christian children attended. At that time, they became more aware of their Jewish background. As Ellen described, “[i]n Germany, religious instruction was part of the overall curriculum and was taught during regular school hours by clergy of each denomination.” Pine, p. 20. Ellen and Hannelore were taught by their cantor and received instruction in Hebrew and Bible stories.

The family had Shabbat dinners with their Mayer grandparents and celebrated the Jewish holidays together. The Kann family also liked to travel, and Ellen recalled family trips to the Netherlands, Yugoslavia, Switzerland, and Austria during her childhood.

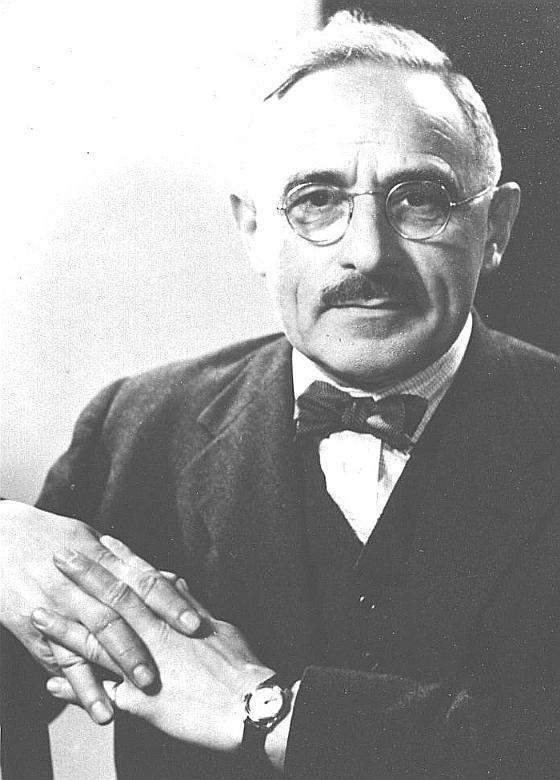

Ellen’s uncles Wilhelm and Ernst, the sons of Mathilde Gross and Marx Mayer, were also living comfortable lives in Germany in the years before Hitler came to power. Wilhelm became a renowned psychiatrist. According to Edward Shorter’s A Historical Dictionary of Psychiatry (Oxford University Press, Feb 17, 2005), Wilhelm studied medicine at the University of Heidelberg and then further specialized in psychiatry at Heidelberg. His doctoral thesis was on “the phenomenology of abnormal feelings of happiness,” and by 1929, he was an assistant professor of psychiatry in Heidelberg.

On the personal side, according to Shorter’s book, Wilhelm had married in 1919; his wife was Carola Meyer, and they had one child. Around the time of his marriage, Wilhelm adopted the surname Mayer-Gross, hyphenating his mother’s maiden name with his father’s surname.

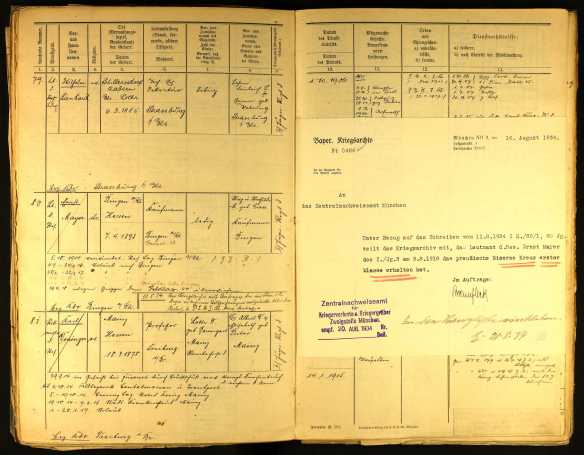

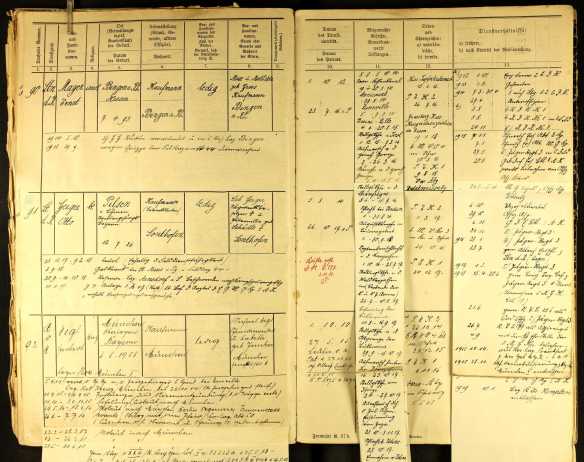

Wilhelm’s younger brother Ernst served in the German military during World War I. Once again Matthias Steinke helped me out and translated the documents reporting Ernst’s military record. According to Matt’s translation, Ernst served in the military first from October 1907 until September 1909 as a private in the 9th Infantry Regiment in Zabern. Then when World War I started, he was on active duty from August 1914 until September 1918, again serving in the infantry. He was a bona fide war hero for Germany.

He fought in over twenty battles all over Europe: in France, in Italy, in Bukovina and Slovenia, and at the border of Greece. On the 5th of October he was shot in the back during a battle near Lille, France, but returned to the front by June, 1915, where he fought in a battle near Tirol. Beginning in December, 1914, he served as a ski trooper for some of his time in the army. His service ended when he was sent to the hospital in September, 1918, with influenza. His rank at the end of his service was a reserve lieutenant. He received several commendations for his service including the Prussian Iron Cross, the Edelweiss medal, and two Hessian orders.

Bavaria, Germany, World War I, Personnel Rosters, 1914-1918, for Ernst Mayer

Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv; Mnchen; Abteilung IV Kriegsarchiv. Kriegstammrollen, 1914-1918; Volume: 11697. Kriegsstammrolle: Bd.1

Bavaria, Germany, World War I, Personnel Rosters, 1914-1918, for Ernst Mayer Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv; Mnchen; Abteilung IV Kriegsarchiv. Kriegstammrollen, 1914-1918; Volume: 11697. Kriegsstammrolle: Bd.1

After the war, Ernst became the owner of a successful publishing house in Berlin, Mauritius Verlag. He married Helene Hirschberg, and they had two daughters and were living in Berlin.

Thus, as of 1933, Mathilde (Gross) and Marx Mayer and their three children were successful citizens of Germany. The world and lives of all these members of the family changed drastically with the election of Hitler as chancellor in 1933.

Ellen Kann Pine was then twelve years old and remembers well how things changed in Bingen. She wrote:

As soon as Hitler became chancellor, fierce looking men wearing different colored uniforms appeared everywhere. … Part of the uniform was a red armband with a large black swastika on a white background. Almost all teenagers of both sexes belonged to the Hitler Youth and wore similar brown uniforms and red armbands. They all were disturbing and frightening as they marched in the streets day and night carrying Nazi flags and singing Horst-Wessel Lied and other vicious anti-Semitic songs. Swastikas were painted everywhere: on walls, on buildings, on flags, and on women’s brown blouses. ….

It was soon obvious that the anti-Semitic propaganda and lies that abounded in the streets had their desired effect. It helped turn our previously friendly and courteous Christian neighbors and their children into hostile anti-Semites. Now we rarely went for walks, and when we did, we kept strictly to ourselves. We could not go shopping, or to the movies, or a theater, since most of these activities were out of bounds for Jews.

Pine, pp. 35-36.

Things changed for Ellen and her sister at school as well because they were Jewish. Friends ignored them, as did their teachers.

Adding to the family’s stress and sorrow was the heartbreaking death of Mathilde’s husband and the family patriarch, Marx Mayer. Ellen wrote:

Our beloved Opapa died in 1934. It was the first family death we experienced and it was wrenching. I cannot forget the look on our Omama’s face when we came to visit her. Sitting on the sofa, she looked utterly lonely and sad with grief.

Pine, p. 29

After September, 1935, with the passage of the Nuremberg Laws, Ellen and her siblings could no longer attend school at all. Their father also lost his job as director of a synthetic fertilizer company. The family made the important but painful decision to send the twins and their younger brother to boarding school in England. For two years from 1936 until 1938, the children lived away from their parents. Ellen wrote movingly about the experience and the issues the children had adjusting to life away from home.

Fortunately their uncle, Willy Mayer-Gross, was in England and was a source of comfort and support for the children while they lived there. The Nazi laws prohibiting Jewish doctors from practicing medicine on non-Jewish patients and other restrictions had led Willy to emigrate in 1933. He was able to obtain funding through a Rockefeller Foundation grant to go to England to work and live. His niece Ellen Kann Pine wrote this about her uncle Willy:

Learning a new language, a new culture, new ways of treating patients, and having to retake his medica exams made his first years there very difficult. Although Uncle W. was in his forties he persevered, brought his family to England and was able to continue his research. … He was our guardian and his support was invaluable when my sister and I entered boarding school in England in 1936.

Pine, p. 32

Willy did in fact have a remarkable career in England; Edward Shorter described him as the “Importer of German scientific rigor and psychopathological thinking to English psychiatry.” A Historical Dictionary of Psychiatry (Oxford University Press, Feb 17, 2005).

According to the Whonamedit website:

In the 1933 Mayer-Gross came to the Bethlem Royal Hospital, London, to work with Edward Mapother, who provided fellowships for German academics who were fleeing Hitler, such as Guttmann and Mayer-Gross. He worked at the hospital from 1933 to 1939, when he became a licentiate of the Royal College pf Physicians and the Royal College of Surgeons. He subsequently became senior fellow with the department of experimental psychiatry, Birmingham Medical School 1958; Director of Research, Uffcalme Clinic. He was a fellow of the British Eugenics Society 1946, 1957. It was Mayer-Gross who first suggested, in about 1955, that tranquilizers converted one psychosis into another. Wilhelm Mayer-Gross was the winner of the Administrative Psychiatry Award for 1958.

Willy’s younger brother Ernst also suffered due to the Nazi persecution of Jews. Despite his distinguished service to Germany during World War I, like other Jewish business owners he was forced to sell his publishing business in accordance with the Nazi policies requiring “Aryanization” of all businesses. Like his brother Willy, Ernst decided to leave Germany once he’d lost his business.

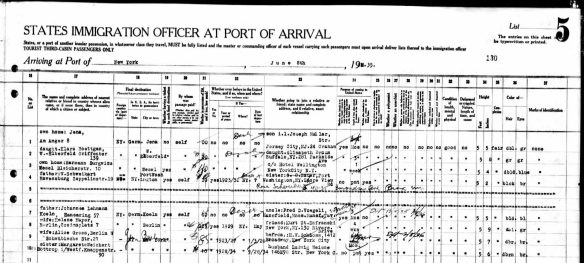

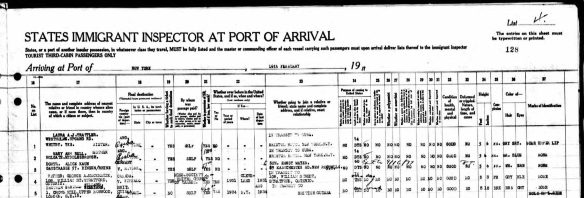

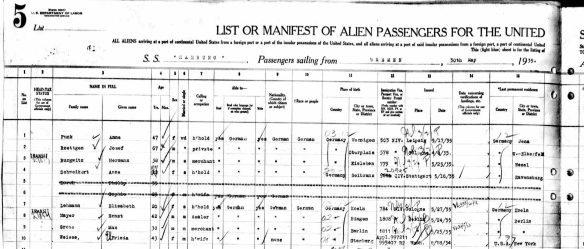

He arrived in New York on June 8, 1935, leaving his family behind until he could bring them over as well.

Ernst Mayer passenger manifest, June 8, 1935, line 8 Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867.

Among their early clients were the magazines Life, Look, The Saturday Evening Post, and Collier’s, which retained their services for the procurement of photographs. The Black Star company’s website describes Ernst’s important role in the success of Black Star:

It was Mayer who made the decisive step uptown into the Rockefeller Center to Time Inc. He brought with him an enormous pile of essays from photographers including Fritz Goro and Paul Wolff, whom he had brought safely from Berlin to New York. Soon after, the chief editors of Life Magazine had chosen Black Star as one of their main suppliers of pictures. Emigre photojournalists viewed the agency as their best means of gaining access to the magazine. For the mostly Jewish photographers, Black Star was a piece of Europe in the middle of New York.… According to photo historian Marianne Fulton, Life brought Black Star 30 to 40 per cent of its business. Black Star, in turn, contributed to Life becoming the most popular magazine in America for nearly three decades, with tens of millions of readers.

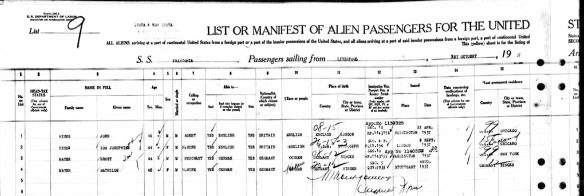

A little over a year after arriving himself, Ernst was able to bring his wife and daughter to the United States on August 11, 1936.[2]

![Ernst Mayer and family passenger manifest August 11, 1936 Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/ernst-mayer-and-family-august-1936-manifest-p-2.jpg?w=584&h=619)

Ernst Mayer and family passenger manifest August 11, 1936

Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867.

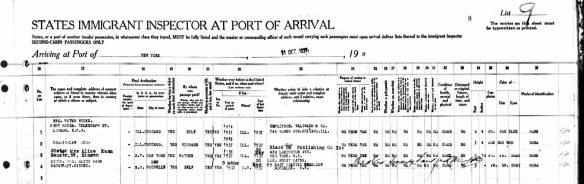

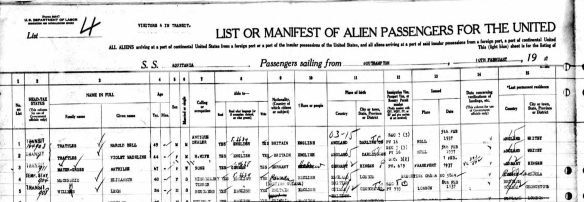

One year after that, on October 11, 1937, he returned once more to Germany to bring his mother Mathilde back to the US.[3] As you can see, the manifest shows they left from England, not Germany. Ellen Kann Pine wrote that her grandmother Mathilde came to see her and her sister at boarding school in England before leaving for the US.

Mathilde Mayer and Ernst Mayer on passenger manifest, October 11, 1937 Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867.

In August, 1938, the daughters of Alice Mayer Kann, Ellen and Hannelore, left England to come to the US. Their parents and brother followed a month later, and the Kann family also settled in New Rochelle, New York. Thus, by the fall of 1938, just a few months before Kristallnacht and the increased violence against Jews in Europe that followed, all of Mathilde’s children and grandchildren were safely out of Germany, as was she.

I will leave for another day what Mathilde’s life was like once she got to America—that is, until I can read the rest of her memoir. As for her granddaughter Ellen Kann Pine, like her two uncles Willy and Ernst, she not only survived, she thrived—she worked hard, ultimately obtained a Ph.D. in biochemistry, and became a successful research scientist. I highly recommend her memoir as another lesson in the resilience of people and their ability to start life over in a new place and find not only security but happiness. Her book is available on Amazon here.

Sadly, Ernst Mayer’s wife Helene Hirschberg died on July 19, 1945, at age fifty. Willy Mayer-Gross died in 1961; he was 72. Mathilda outlived her oldest child, dying at 100 in 1969. Her other two children also lived long lives. Ernst died at ninety in 1983, and Alice died in 1993 when she was 97. Her husband Arthur Kann had died many years before in 1966 when he was 83.

My cousin Mathilde had suffered greatly during her life: she had lost her parents in a terrible tragedy, her husband had died too soon, and she had been forced to leave her homeland and the place where her family had lived for hundreds of years. But she and her three children and all of her grandchildren escaped Nazi Germany in time and survived. Although all of them suffered from the Nazi treatment of Jews, they all found success. It’s hard to say they were lucky, given what they’d endured, but they at least survived.

Other members of their extended family were not as fortunate.

[1] Later posts will relate what happened to Mathilde’s siblings and their families.

[2] Ernst and Helene Mayer had another daughter Dorothea, who had died before the family left Germany.

[3] It appears that Mathilde was listed on an earlier ship manifest to leave Germany in February, 1937. There is a notation “Ext. 9/17/37,” which I assume meant she extended her ticket for an additional seven months. Perhaps she did not want to sail alone, and it was only when Ernst returned to bring her back in October that she came to the US. Or maybe she did come in February and returned because there is another notation that says “RT.” Return trip? I am not sure.

Mathilde Mayer-Gross listed on February 1937 manifest Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867.

Very interesting post, Amy ~

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Laurel. Very sad.

LikeLike

Fascinating. I am so happy the family made their way to America and went on to lead long and successful lives.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sadly, the next chapter in this story about Mathilde’s sister does not have that happy ending.

LikeLike

I agree very sad. That period of history is one of great sorrow. So few people understand today what happen and the enormity of the events that played out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, which is why it’s so important to keep telling these stories of individual people and what happened to them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: A Family’s Life Destroyed: The Story of Anna Gross | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Mathilde’s Brothers: Wilhelm, Isidor, and Karl Gross | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

I have the book now – it came very quickly. Looking forward to reading it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You read German—I am envious!

LikeLike

Pingback: Bingen: The Early Home and the Last Home in Germany for Many in the Seligmann Family | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Seligmann updates: The work is never done | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Four Years of Learning German | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Willy Mayer-Gross had a huge influence on British psychiatry, and by extension, all English-speaking psychiatry in the mid 20th century. His textbook, Clinical Psychiatry, was the “Bible” of the profession for a time. He influenced key disciples, like Martin Roth, who spread his perspective in British and world psychiatry. It’s important to note he wasn’t given access to political power within the profession: he wasn’t at London or Oxford or Cambridge. But from his provincial base, his influence grew because of the power of his ideas.

Some of us think that his ideas were lost too soon, with the transition of psychiatry in that era, especially in the US, away from its German roots (which were less respectable due to Nazism) to the new Freudian approaches (which were associated with rejection of Nazism since Freud and his circle were mostly Jewish). Due to his writing an English language textbook, Mayer-Gross was a key link between the old German psychiatry and the new Anglo-American one, which remains most prominent today. But it is a link that hasn’t survived as well as it should have.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s fascinating! Thank you so much for sharing these insights into Willy Mayer-Gross and into the history of psychiatry in general.

LikeLike