Emily Goldsmith was the fourth child of Abraham Goldsmith and Cecelia Adler to live to adulthood. She was born in Philadelphia on April 30, 1868.1 Her mother died on November 8, 1874, when Emily was only six years old.

On January 28, 1892, Emily married Felix Napoleon Gerson, the son of Aron Gerson and Eva Goldsmith—who was not related to my Goldsmith family, as I wrote about here. According to his entry in Who’s Who in Pennsylvania, Felix went to Philadelphia public schools and then studied civil engineering; in the 1880s he served in the department of the Chief Clerk, Philadelphia & Reading Railway Company, and then in 1891 he changed careers and became the managing editor of Chicago Israelite. In 1892, Felix became the managing editor of the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent.

Emily Goldsmith Gerson. Courtesy of the Goldsmith family

Emily and Felix’s first child Cecelia was born on October 27, 1892.2 She must have been named for her grandmother, Emily’s mother Cecelia Adler Goldsmith. A second daughter, Dorothy, was born on June 2, 1897.3

I was delighted to discover that Emily, like her older brother Milton, was an author of children’s stories, books, and plays. Beginning in the 1890s, Emily contributed children’s stories regularly to the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent where her husband Felix was the managing editor. I counted over twenty stories written by Emily that were published between 1895 and 1899.

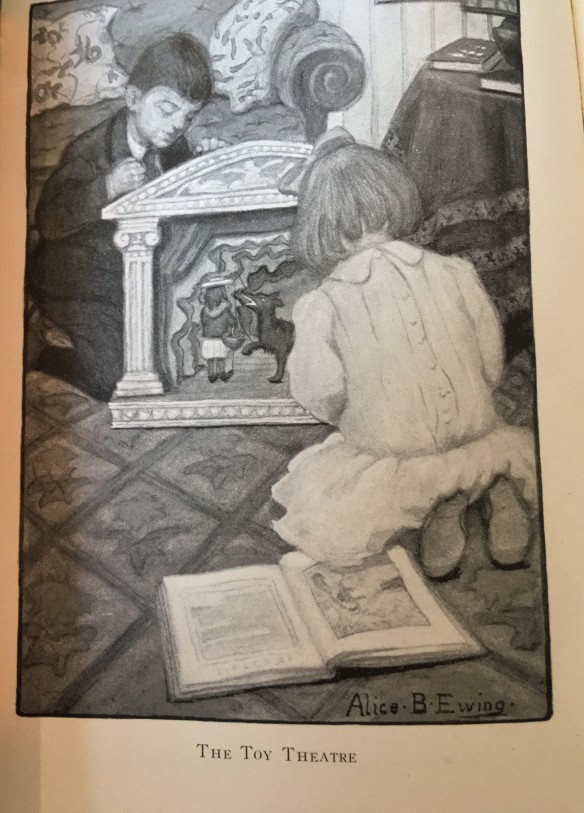

For example, on April 17, 1896, (p. 5), the Jewish Exponent published Emily’s story, “Joseph’s Toy Theater,” about a little boy who received a toy theater as a gift and refuses to share it with his sister. When the puppets in the theater come to life at night, he hears them criticizing his selfishness and threatening to punish him. He then goes to his sister’s room and gives her one of the puppets from the theater. (The illustration below is by Alice B. Ewing and appeared when this story was republished in The Picture Screen, as discussed below.)

On October 9, 1896, (p. 5) the Jewish Exponent published “Helping Mother,” another of Emily’s short stories, this one about a little girl who helped her mother by playing on her own while her mother worked.

These and the other stories written by Emily Goldsmith Gerson and published in the Jewish Exponent are quite short and usually have some lesson teaching children about good behavior. In addition to her stories, Emily also wrote plays for children to perform for the Jewish holidays such as Purim and Hanukkah.4

In 1900, Emily, Felix, and their daughters were living in Philadelphia., and Felix was working as an editor. Emily did not report an occupation, but she continued to contribute her stories during the next decade.

Emily and Felix Gerson and family 1900 US Census

Philadelphia Ward 20, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Page: 4; Enumeration District: 0433

Ancestry.com. 1900 United States Federal Census

Emily not only continued to write short stories for the Jewish Exponent; she also published books and plays for children. Her earliest published book was The Picture Screen, published by George W. Jacoby & Co. in 1904. According to this brief description in the list of suggested Christmas books in Book News, the book is a “unique juvenile consisting of stories told about the pictures on a big picture screen. A little girl’s mother tells her and her brother the tales while the little girl lies helpless with a sprained ankle.”5

The book reached an audience far beyond Philadelphia, as seen in this review that appeared in the Buffalo Enquirer on July 9, 1904 (p. 2):

I obtained a copy of the book, and it is as described in the reviews. Some of the stories the mother tells the children are stories Emily had previously published, including the one about Joseph and the toy theater that I described above. They all teach the children something about being a good person. The book was dedicated to Emily’s daughters, Cecelia and Dorothy.

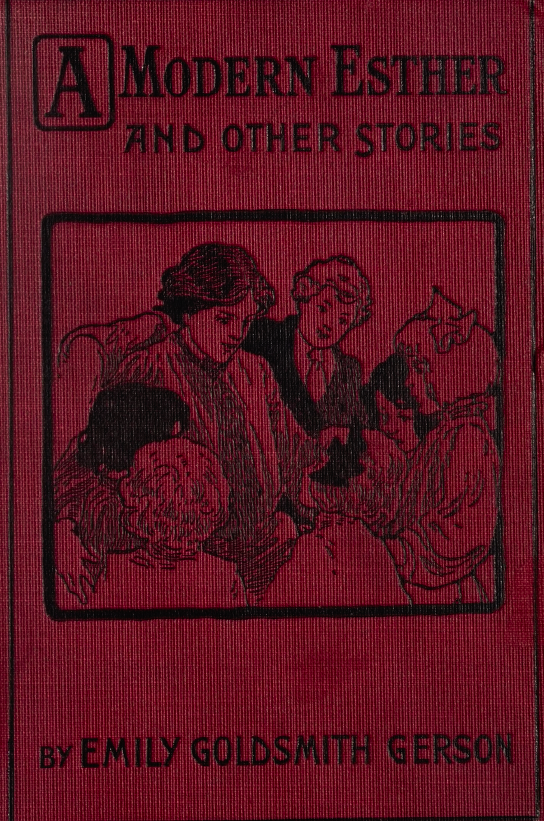

Then in 1906, Emily published A Modern Esther and Other Stories for Jewish Children (Julius H. Greenstone, Philadelphia, 1906), another collection of short stories and two short plays; she dedicated the book to her father Abraham, who had died just a few years before. The title story is about a girl born somewhere in a shtetl in Europe, the daughter of the rabbi, who bravely goes to the local governor to stop the anti-Semitic attacks on her family and community. Many of the stories have a religious theme; for example, one is about a little girl discovering faith in God, and several are about God saving families from poverty or from illness. Often the stories are connected to a Jewish holiday. You can find this collection of Emily’s works online here.

The reviewer for the New York Times wrote that “the author’s object is not so much fiction as the encouragement of piety and the teaching of the simpler lessons of the faith to which she belongs, to show how pleasant and profitable it is—in the end—to do those things which are commanded, how faith and honest and kindness win their sure reward, and how wickedness is punished…..Naturally the stories are of extreme artlessness—-but all of us in our time have read stories of like artlessness not without eager ears and open eyes.”6

Emily also published several of her holiday plays for children, including Ten Years After, A Purim Play (1909), A Delayed Birthday, a play for Hanukkah published by Bloch Publishing Company in 1910, and The Purim Basket, another Purim play published by Bloch Publishing Company in 1914.

Emily’s daughter Dorothy seems to have enjoyed theater also. In March 1914, when she was sixteen, she appeared on stage in a production put on by the French department of Girls High School in Philadelphia.7 That is Dorothy on the far left.

Emily’s career as a children’s author was, however, cut short. She died from pancreatic and liver cancer on November 28, 1917. She was only 49 years old and was survived by her husband Felix and her two daughters. She was also survived by her eight of her nine siblings, the other surviving children of Abraham Goldsmith.

Emily Goldsmith Gerson death certificate

Pennsylvania Historic and Museum Commission; Pennsylvania, USA; Certificate Number Range: 121031-124420

Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1966

But Emily was not forgotten. A camp for underprivileged Jewish girls was established in her memory, known as the Emily G. Gerson Farm.8 In 1920, her synagogue, Keneseth Israel in Philadlephia, dedicated a stained-glass window in her memory. In reporting on the dedication, the Dallas Jewish Monitor stated that Emily had been the first president of the Keneseth Israel Sisterhood and was “deeply interested in all things appertaining to the good and welfare of the Temple.”9

Stained glass window dedicated in memory of Emily Goldsmith Gerson in 1920 by Keneseth Israel Congregation as depicted in The Philadelphia Inquirer, December 5, 2004, p. C04

The window still exists and was depicted in the Philadelphia Inquirer on December 5, 2004, when it was being being exhibited at Congregation Keneseth Israel’s Judaica museum in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania. The caption under the photograph of the window stated that it was presented with the inscription from Proverbs 31:26: “She opened her mouth in wisdom and the law of kindness is on her tongue.”10

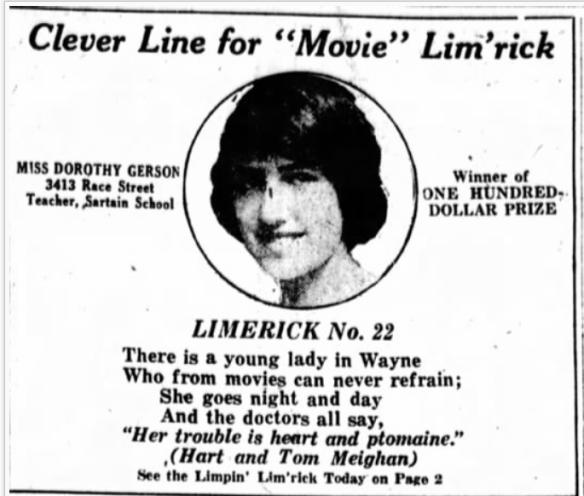

The 1920 census reported that Emily’s widower Felix continued to work as a newspaper editor. Her daughters were also working. Cecelia, now 27, was a secretary in a doctor’s office, and Dorothy, 22, was a public school teacher.11

Later that year Cecelia married Malvin Herman Reinheimer in Philadelphia.12 Malvin was the son of Samuel Reinheimer and Julia Lebach and was born in Cameron, West Virginia, on January 26, 1891. His father was in the wholesale clothing business. Malvin graduated from Swarthmore College in 1912 where Cecelia had also been a student; perhaps she met him there. Malvin then graduated from the University of Pennsylvania School of Law in 1915 and was practicing law in 1920 and living in Philadelphia with his father and sisters. He had served stateside in the US military during World War I.13

On November 29, 1921, Cecelia and Malvin had their first child, a daughter they named Emily Gerson Reinheimer in memory of Cecelia’s mother Emily Goldsmith Gerson.14 A second child was born a few years later.

Meanwhile, Dorothy revealed that she had some of her mother’s writing talents when she won a prize for best limerick in 1921:

The 1930 census record for Felix and Dorothy is a complete mystery. First, it has Dorothy listed as Felix’s wife and says Felix was 38 when in fact Felix was 68. It says Felix was 31 when they first married, and Dorothy was 26. Then it says Felix was a salesman in a dress shop, and it has no occupation listed for Dorothy. There were also four men lodging with them. How much of this can I trust? Is this a different Dorothy and Felix Gerson? Not likely—they were still living at 3415 Race Street, the same place they were living in 1920.

Felix Gerson and Dorothy Gerson 1930 census, image modified

Census Place: Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Page: 27A; Enumeration District: 0397

Ancestry.com. 1930 United States Federal Census

There is no indication from any other records that Felix had left his newspaper career or that Dorothy had stopped working. In fact, the 1930 Philadelphia city directory lists Dorothy as an advertising manager for Oppeheim Collins & Company and Felix as the president-manager of the Jewish Exponent.15 That 1930 census record indicated that Dorothy was the person providing the information to the enumerator—would she have lied about her relationship with her father, his age, and their occupations? Or was the enumerator just sloppy? I don’t know.

Fortunately, there was no confusion in the 1930 census record for Cecelia Gerson and her husband Malvin Reinheimer and their children. They were all living in Philadelphia where Malvin continued to practice law.16

After almost twenty years of being a widower, Felix remarried at age 73. On August 31, 1936, he married Emma Brylawski, who was also an editor and journalist at the Jewish Exponent.17

Not long afterwards, in about May, 1937, Felix’s daughter Dorothy Gerson moved to Middletown, Connecticut, where she was working as an advertising manager for Wrubel’s Department Store, according to the Jewish Exponent of February 25, 1938.

The 1940 census records for Felix and his daughters show that Felix and his second wife Emma were living in Philadelphia without any listed occupation,18 that Dorothy was an advertising manager living in Middletown, Connecticut,19 and that Cecelia and her family were living in Philadelphia where Malvin was still working as an attorney.20

Cecelia lost her husband Malvin to renal failure and other illnesses on October 24, 1944; he was only 54 years old.21 Then she and her sister Dorothy lost their father Felix a year later on December 31, 1945; Felix was 83 years old.22 Eleven years later on August 12, 1956, Cecelia died at age 63 from lung cancer. She was survived by her two children and by her sister, Dorothy.23 Dorothy, who had returned to Philadelphia around 1950 and lived with her aunt Estelle Goldsmith, died at age 80 in January 1978.24

Emily Goldsmith Gerson’s story is in many ways such a sad one. She lost her mother Cecelia Adler Goldsmith when she was only six years old. She named her first child Cecelia in memory of her mother. Then she herself died young, ending a promising career as a children’s writer and leaving behind her own daughters. Cecelia, the daughter named for Emily’s mother, then later named her first child for her own mother, Emily. The family’s alternating naming pattern reveals Emily’s sad story. But she left behind her works and her descendants, and I hope that by telling her story I have honored her memory.

-

Emily Goldsmith Gerson, death certificate. Pennsylvania Historic and Museum Commission; Pennsylvania, USA; Certificate Number Range: 121031-124420.

Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1966. Certificate Number: 124162. ↩ - Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1966 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania ↩

- Number: 161-05-1973; Issue State: Pennsylvania; Issue Date: Before 1951. Source Information Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014 ↩

- The Jewish Exponent, March 4, 1898, p. 8 (Purim play). The Jewish Exponent, December 8, 1899 p. 9 (Hanukkah play). ↩

- Book News (1905, Philadelphia), p. 361. ↩

- “For Jewish Children,” The New York Times, March 31, 1906, p. 21. ↩

- “High School Girls Give Merry Play,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, March 14, 1914, p.2. ↩

- “Emily G. Gerson Farm Dedicated,” The Philadelphia Jewish Exponent, June 27, 1919, p. 2. ↩

- “Unveil Tribute to First President,” Dallas Jewish Monitor, June 25, 1920, p. 5. ↩

- “Hebrew Bible in Glass and Light,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, December 5, 2004, p. C04. ↩

-

Felix Gersons and daughters, 1920 US Census, Census Place: Philadelphia Ward 24, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Roll: T625_1627; Page: 2A; Enumeration District: 688.

Ancestry.com. 1920 United States Federal Census ↩ - Cecelia Gerson and Malvin Reinheimer marriage, Ancestry.com. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Marriage Index, 1885-1951. Original data: “Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Marriage Index, 1885–1951.” Index. FamilySearch, Salt Lake City, Utah, 2009. Philadelphia County Pennsylvania Clerk of the Orphans’ Court. “Pennsylvania, Philadelphia marriage license index, 1885-1951.” Clerk of the Orphans’ Court, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Marriage License Number: 432189. ↩

- Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, WWI Veterans Service and Compensation Files, 1917-1919, 1934-1948; Pennsylvania Historic and Museum Commission; Pennsylvania, USA; Certificate Number Range: 091401-093950; Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1966. Ancestry.com. U.S., School Catalogs, 1765-1935 (Swarthmore, 1912; University of Pennsylvania, 1915). ↩

- Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Original data: Social Security Applications and Claims, 1936-2007. SSN: 180129263 ↩

- Philadelphia City Directory, 1930, Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995. ↩

- Malvin Reinheimer and family, 1930 US Census, Census Place: Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Page: 13A; Enumeration District: 1029. Ancestry.com. 1930 United States Federal Census ↩

- Ancestry.com. New York, New York, Extracted Marriage Index, 1866-1937. Certificate Number: 24190. ↩

- Felix and Emma Gerson, 1940 US Census, Census Place: Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Roll: m-t0627-03692; Page: 12A; Enumeration District: 51-158. Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census ↩

- Dorothy Gerson, 1940 US Census, Census Place: Middletown, Middlesex, Connecticut; Roll: m-t0627-00512; Page: 13A; Enumeration District: 4-23. Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census ↩

- Malvin and Cecelia Reinheimer, 1940 US Census, Census Place: Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Roll: m-t0627-03754; Page: 1B; Enumeration District: 51-2169. Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census ↩

- Pennsylvania Historic and Museum Commission; Pennsylvania, USA; Certificate Number Range: 091401-093950. Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1966. Certificate Number: 93778. ↩

- Pennsylvania. Historic and Museum Commission; Pennsylvania, USA; Certificate Number Range: 108301-110850. Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1966. Certificate Number: 110070. ↩

- Pennsylvania Historic and Museum Commission; Pennsylvania, USA; Certificate Number Range: 074701-077400. Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1966. Certificate Number: 75270 ↩

- Number: 161-05-1973; Issue State: Pennsylvania; Issue Date: Before 1951. Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014. Family source regarding her move back to Philadelphia. ↩

Emily sound like an extraordinary woman. I really enjoyed learning about her creative work.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks so much, Leslie. I am always so excited to find an author among my long-lost relatives.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a special family. I Love reading about Emily and her brother.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you—I have so enjoyed researching this family. I enjoy all the research, but these Goldsmiths have really worked their way into my heart.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a wonderful woman Emily was and so talented! It makes you wonder what else she might have created if she’d lived longer.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I know…that makes me very sad. Thanks, Debi!

LikeLike

My psychological interpretation 😉 is that Emily was mothering herself as an adult by writing children’s stories and plays. I loved reading about her. That one piece of criticism was interesting–it seemed to be saying the piece was didactic, but that as children we often lap up books that teach us something in such a clear manner. Since most children’s literature of the time was didactic and considered important to a child’s education, I don’t know why they even bothered to say so!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I like your psychological interpretation. But what does it say about us that we write about dead ancestors we never knew?

I also thought that critic’s comment was superfluous. But don’t critics always have to find at least one negative thing to say? I read the stories, and they are simplistic and moralistic, but yes, that’s what children’s literature was like back then—to the extent there was children’s literature.

Thanks as always for your input!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hahaha, yes, what DOES it mean? I think it means that we are curious and have good imaginations and some research skills. Oh, and stubborn? You are right that almost all children’s lit back then was like that. There are a few rare exceptions, and we know them as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and a couple of others. Very very different from what most parents wanted to buy for their children to read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And The Wizard of Oz. But weren’t both written with adults in mind? I remember reading that Baum intended it as a political message about the gold standard.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Wizard of Oz and Peter Pan are both books that are not that great. The dramas and films that were created from them are better. Alice in Wonderland is truly a brilliant piece of literature for children. Like the best literature for children it’s got a hidden subtext for adults. While we are on the subject my favorite movie is Babe. But the book is in not very good. I guess it doesn’t always hold true that the book is better than the movie.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My favorite childhood books were Charlotte’s Web and The Phantom Tollbooth. I didn’t even want to see the movie versions. I prefer to keep them in my head. I also loved A Wrinkle in Time, but I did take my grandson to see that movie in the fall. It was good, but not nearly as good as the book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Those are wonderful books. I used to teach Charlotte’s Web a lot because it’s a great book for talking about a chapter book. I love children’s lit, especially chapter books. One of my favorites is Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH. The movie is awful in comparison.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have not read the NIMH book—I think it was not around when I was the right age for reading it. It’s actually quite remarkable how many of my childhood books were published in the 1950s and early 1960s when I was a pre-adolescent. What did children read before then besides stories like those Emily wrote? The Bible?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just read Emily’s story ‘A Modern Esther and I must say that I was quite touched by it. Unfortunately, many people reading the story today may not appreciate it as much any more as they may not know the wonderful story of Queen Esther. Thanks for another great post, Amy! Perhaps you would like to write a description of the collection of stories on the website. It stated there: There’s no description for this book yet.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Good idea, Peter. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You most certainly have honored her memory. What a great post! I would be curious to know how many of her descendants know about her rich history as an author, or if they even have copies of her books? I am reminded by this of something that happened at work that shocked me this year, a high school Jr played her fathers favorite song, a John Lennon song. I remarked something like oh John L., one of the Beatles and she had no idea he was one of the Beatles. The hardest part of me is realizing how so much is lost and not carried forwarded….so thats why my thoughts go to do her descendants know how accomplished she was – I certianly hope so. I am so happy you have posted this for future generations to find 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wow, someone has never heard of the Beatles? Even my grandson knows who they were. Certainly my kids do.

As for Emily’s descendants, I haven’t been in touch with them. But I have to believe that they do know. After all her granddaughter was named for her and must have been told about her grandmother.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amy, I’m so happy you were able to find many reviews of Emily’s books, as well as the illustrations. Her descendants will surely draw closer to her through these findings. It’s not always easy to pull all these pieces together. How long were you researching Emily’s works?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Emily. Gee, I never keep track of that. My research usually goes in three stages—an initial one when I get the low hanging fruit just to put a family together—census records, e.g.–records that pop up on Ancestry almost immediately. Then later I delve into each individual, looking for the more hidden records and newspaper articles. Then I write up what I have, which helps me see what I am missing, and I go back and search for answers to those questions. Then I edit and re-check and edit, and if I still have questions, I ask them for help on FB and on the blog! So it can stretch over months or weeks depending on the person. I didn’t know about Emily’s books, for example, until I did a newspaper search and found her obit that mentioned she was a writer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your time is put to good use. I usually have to move very quickly because of fluctuations in my work schedule so I never get the in-depth research results like this. When there is more time to dedicate to researching I think it becomes a treasure hunt. Like finding Emily’s books was like discovering some of the hidden goodies inside the treasure chest.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a perfect metaphor! It does feel like a treasure hunt!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is such a wonderful article to honor her!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!!

LikeLike

A wonderful tribute to Emily. The critic’s use of the word artlessness had me looking it up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am not sure how it was intended—as meaning it was without art or more, as I hope, that it was not phony, but sincere and guileless.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Amy, when I saw the illustration of The Picture Screen it reminded me of the What Katy Did series. Very sad Emily died so young. I can imagine how excited you were to find out about her

being a novelist like her brother Milton.

LikeLike

Hi Shirley—I had to look up What Katy Did as I’d never heard of it. Isn’t that strange that an American hasn’t heard of it but you, all the way across the pond, have? I will have to check it out in more depth. And yes, I was very excited to learn that she was a writer!

LikeLike

I loved reading this post, so much of it resonates with me… and my Mum… thank you.

I have included your blog in INTERESTING BLOGS in FRIDAY FOSSICKING at

https://thatmomentintime-crissouli.blogspot.com/2018/05/friday-fossicking-may-18-2018.html

Thank you, Chris

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much! I will have to check out your blog also!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome. I have a few, Amy, they are listed on each blog…

LikeLiked by 1 person

OK, I will take a look.

LikeLike

Pingback: Estelle Goldsmith: Woman of the World | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Wow, so many writers in your family. Emily sounds like a sort of Jewish Enid Blyton (she was an English writer of children’s books whose stories were very moralistic in many ways, though she wrote much later than Emily.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not familiar with that author, but there certainly was once a very moralistic strain in children’s literature. Thanks for reading!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Alfred Goldsmith: Star-Crossed Lover? | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Kissing Cousins…. | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Milton’s Family Album, Part XIV: Teasing His Little Brother | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Milton Goldsmith’s Album, Part XVI: His Beloved Sister and Fellow Author, Emily | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey