Last fall I got into a discussion with a fellow blogger, Luanne at The Family Kalamazoo, about preserving all our work. What happens if WordPress crashes some day? What if the Internet becomes a thing of the past like VCRs and turntables? All our hard work could be for naught. Our grandchildren won’t know a thing about their ancestors and will have to start all over again.

I’d also been getting requests over and over again from my father. He wanted me to print out all my blog posts. He said it was too hard to go back and find earlier posts. I told him that printing them out would not work well because I’d lose all the formatting, and he’d end up with hundreds of pages of posts all in reverse chronological order. (I did explain that new posts had links back to related posts, but he wanted a hard copy.)

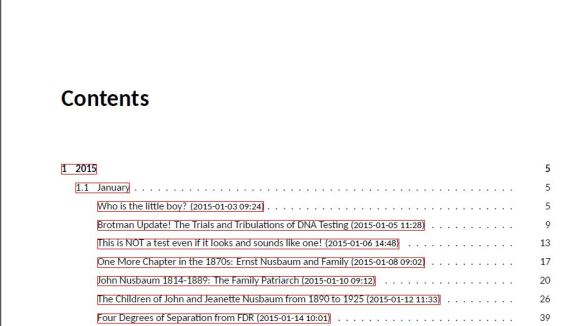

So I decided to explore some options. And what I found was a site called blogbooker.com. It’s a free site that converts your blog into PDFs. But not just that. It creates a table of contents using your blog post titles and puts everything in chronological order. I was very excited by the results.

But then I still had well over a thousand pages of PDFs, and printing all of them would still lead to an unmanageable pile of paper that no one would be able to use easily. Plus the ink I’d use in printing them would be costly.

Fortunately, blogbooker also suggested several sites where you can turn those PDFs into a published book—either an e-book or a full-fledged hard copy bound book. The one I chose was Lulu.com. I looked at the various options, and for cost reasons I chose to print the blog in a paperback format on 8 by 11 sized pages in black and white. Since I did this after blogging for fifteen months, I had to break the blog into four volumes. That meant creating separate PDFs on blogbooker for four different volumes. No big deal. It’s easy enough, and remember that blogbooker is free.

Lulu.com is not free, at least not for hard copy printed books, but it is really reasonable. Each volume cost me about $15 a copy, and I made two copies of each, one for me and one for my parents. At least now my parents can flip through the pages and find older posts, and I can sleep a little more easily, knowing that there are two hard copies of my blog. And they really look quite nice—I was pleased with how they came out. The photos and graphics are not as clear as on the Internet, but they are adequate, and the text is all there as are all the comments.

I’ve just created and ordered Volume Five, covering from January 1, 2015 through April 21, 2015. (If there are any family members or even just interested readers who want a volume, let me know. 🙂 )

What do you do to preserve your work? How do you make sure that all your research and documents and photographs are going to be safe and accessible for another 100 years or more?