Last week in my post about my great-grandfather’s siblings and their immigration to the United States between 1866 and 1872, I wrote about one of his presumed brothers, Julius. Although Julius was mentioned in the Beers biography of Henry Schoenthal as one of the siblings, I could not find any other source to verify that the Julius Schoenthal whom I had located was the right one. The Beers biography gave no details about Julius other than that he was living in Washington, DC, at the time it was written (1893). The Julius Schoenthal I had found did live in DC, but aside from that one clue, there was nothing else that linked him to his presumed siblings in Pennsylvania.

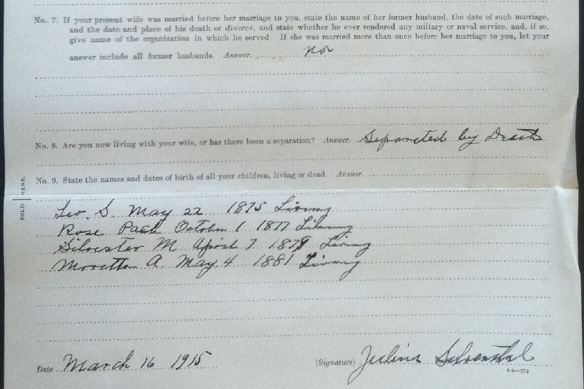

What I did learn about that Julius, as described in my earlier post, was that he was born sometime between 1845 (1900 and 1910 census records) and 1847 (the 1880 census) that he had served in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870-1871, that he had married a woman named Minnie Dahl in 1874, , that he was a shoemaker (like his presumed father, Levi Schoenthal), and that he had four children: Leo (1875), Rosalia (1876), Sylvester (1878), and Moretto (1879). I also was able to find his card in the Civil War pensions database, which indicated that he had served in the Signal Corps in the US Army; with the help of Lillian from Facebook, I also knew he had enlisted from Chicago in 1873 and been discharged in 1874 in Washington, DC. What I did not know for sure was whether or not he was in fact the son of Levi Schoenthal, my great-great-grandfather.

I also did not know when he’d arrived in the US. Then I found a reference to a Julius Schoenthal in an article entitled “History of the War in Europe” in the Washington, Pennsylvania Review and Examiner, dated July 12, 1871 (p.3); he was acting as an agent for a the National Publishing Company of Philadelphia, which had published a book about the Franco-Prussian War. After a review of the book, the article ends by saying, “It is for sale by subscription only, and Julius Schoenthal, who is the authorized agent for this section, is now canvassing for it.” Given the name, subject matter, and location, I have to believe that this is Julius, the brother of my great-grandfather, and thus that he was already in the US as of July 12, 1871. He also at least for some time had been in Washington, Pennsylvania, where his siblings and cousins were living.

I sent away for his full pension file. I was fortunate to find Deidre Erin of Twisted Twigs on Gnarled Branches who offers to obtain copies of pension records at the National Archives for a reasonable fee. Within a few days I had an excellent and complete copy of Julius Schoenthal’s pension file.

Although the file was 56 pages long, I found all the information I needed on page 6 where Julius reported both his birth date and birthplace: January 30, 1845, in Sielen, Germany. The fact that Julius was born in Sielen was certainly probative of the fact that he was the son of Levi Schoenthal and Henrietta Hamberg; the fact that he was born before 1846 explained why I had not been able to locate a birth record for him since the online records start in 1846 for Sielen.

As you can see, the page also lists his wife as Minnie Dahl and the names of his four children. For my purposes, those overlapping facts tie the Julius Schoenthal who served in the Signal Corps and lived in Washington, DC, was married to Minnie Dahl, and had four children, to the other Schoenthals living in Pennsylvania, including my great-grandfather Isidore. I still have no idea why he was in Chicago when he enlisted in the Signal Corps.

I also requested a copy of a letter he had reportedly written to President Ulysses S. Grant, according to the index for the archives in the Grant Presidential Collection at Mississippi State University. When I received the materials from Mississippi State University, there were two letters, one in German and in old German script that I could not read; the other in English and quite readable. After I received some help with the first letter from the Genealogy Translations group on Facebook, it was obvious that it was not written by my relative and had been misfiled in the archives. I was disappointed since this was a lengthy letter, and I had hoped for some useful insights.

Fortunately, the second letter was in fact from Julius, my great-grandfather’s brother, but it was not to President Grant, but rather a letter dated 1884 (when Grant was no longer even President) to the then Secretary of the Treasury asking for a job as a watchman or messenger. Julius wrote that he was 38 years old (he actually would have been 39 if born in 1845 as he had claimed in his pension files), a US citizen, a veteran of the Signal Corps, and married with four children. There is also a letter of support included with his letter from a friend who wrote that Julius was “a faithful soldier and would make a very judicious and faithful watchman….” Unfortunately, I do not think Julius was offered the position since all the later references in his pension file as well as DC city directories in the 1890s indicate that he remained a shoemaker.

In fact, I am quite certain he was not working for the government based on this newspaper article dated November 9, 1888, from the Washington, DC Evening Star (p. 8):

Apparently, Julius, still working as a shoemaker, had been accused of being an anarchist because of a red cloth hanging from a pole near his house and had gained some notoriety. His wife told the reporter that the accusation was false and made by someone out of spite. Why would someone be seeking to harm Julius, a shoemaker with four young children? I don’t know. But obviously Julius did not like these accusations and sued another local paper, the Sunday Herald, for libel:

All of this must have taken a toll on Julius. The remainder of the pension file deals with his numerous claims starting in the 1890s for an increase in his pension allowance based on various disabilities . Julius claimed that while serving in the Signal Corps as a driver of the market-wagon, he contracted various ailments that led to rheumatism, heart and lung disease, throat disease, hearing loss, and catarrh. Reading his file made me curious about the Signal Corps and also about his claimed ailments.

According to one source, the US Army Signal Corps “began in 1860, with the appointment of Dr. Albert J. Myer, a physician, as Chief Signal Officer. Under his command, the unit transformed sign language used to communicate with deaf persons into a semaphore system incorporating red and white “wigwag” flags. During the Civil War, the Signal Corps operated air balloons and telegraph machines.” After the Civil War and during the years that Julius Schoenthal served, the country was not at war, and the Signal Corps took on a different mission: weather forecasting. In her book about the history of the Signal Corps, Rebecca Robbins Raines described the recruitment, training, and responsibilities of those who served in the Signal Corps in its role as national weather forecaster:

The Signal Corps selectively recruited personnel for the weather service-only unmarried men between the ages of twenty-one and forty were eligible-and required them to pass both physical and educational examinations. Upon acceptance, the men enlisted as privates and received at least two months of instruction at Fort Whipple. After an additional six months of duty on station as assistants (later extended to one year), followed by further training at Fort Whipple and appearance before two boards of examination, the men qualified for promotion to “observer-sergeant.” After one year’s service, an observer could again be called before a board for yet another examination.

The work of the observer was often demanding. Three times daily he recorded the following data: temperature; relative humidity; barometric pressure; direction and velocity of the wind; and rain or snow fall. The Corps soon added to this list the daily measurement of river depths at stations along many major rivers. The observer also noted the cloud cover and the general state of the weather. Immediately upon completing his observations, the officer prepared the information for telegraphic transmission to the Signal Office in Washington. In a separate journal he recorded unusual phenomena, such as auroral and meteoric displays. In addition to the three telegraphic reports, he made another set of observations according to local time and mailed them weekly to Washington. The Corps also required a separate midday reading of the instruments, but the observer only forwarded the results if they differed greatly from the earlier readings. At sunset he recorded the appearance of the western sky to be used as an indication of the next day’s weather. In case of severe weather, an observer could be on duty around the clock, making hourly reports to Washington.

[Rebecca Robbins Raines, Getting the Message Through: A Branch History of the U.S. Army Signal Corps (Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., 1996), p. 47 (footnotes omitted). Available online here.]

From what I read in his pension file, Julius was a driver in the Signal Corps, presumably driving the observers to their posts for recording the weather. As described in one statement in his pension file made by a fellow Signal Corps member, Julius would often be exposed to inclement weather while driving the “market-wagon” and spent time in the military infirmary as a result of illnesses contracted while serving.

One of those illnesses, catarrh, was an illness I’d never heard of before. Back in 1865 it was described this way by the New York Times:

Catarrh is a disease of the mucous membrane of the nasal passages and those cavities of the head communicating with them. Insignifiacnt as it appears in its first stages, it is apt in its progress to become instrumental in causing the loss or impairment of smell, taste, hearing and sight, and of creating serious constitutional derangements, not unfrequently terminating in consumption.

According to the National Health Service in Great Britain, today catarrh is not considered a condition itself, but rather a symptom of colds, allergies, or nasal polyps. However, the NHS website does say that “[i]n some cases, people can experience chronic catarrh, which is not caused by an allergy or infection and lasts for a long time. The cause of chronic catarrh is unknown but it may be related to an abnormality in the lining of the throat.”

Julius filed numerous claims over many years beginning in the 1890s. From what I can tell, it appears that his claims were repeatedly denied. Whether his illnesses were as severe as he claimed I cannot judge; there were doctors who supported his claims as well as friends, but there were also doctors who concluded otherwise.

In 1899, Minnie Dahl Schoenthal, Julius’ wife, died at 53. In 1900, Julius was living in Washington, DC, with three of his four children, Leo, Rosalia (Rose), and Moretto, who were all in their early 20s. Julius was now working as a “collection publisher.” I am not sure what that means, unless Julius still had some relationship with the National Publishing Company of Philadelphia 30 years after that article in the Washington, Pennsylvania newspaper. His son Leo was a printer, and Moretto was a cabinet maker. Rose was not employed. I cannot locate Sylvester on the 1900 census.

All three of Julius Schoenthal’s sons married in 1901. Sylvester married Alice Butler in Virginia on April 1, 1901. (That marriage did not last, and on December 17, 1905, Sylvester married Bessie Rose.) Moretto, the youngest child, married in 1901 as well; on November 14, he married Annie M. Heath. Their son Arthur Schoenthal was born in 1903. Finally, the oldest brother, Leo, married Fannie Pach on December 18, 1901. They had a daughter named Minnie (presumably for Leo’s mother) on September 28, 1902, nine months after marrying. On March 12, 1905, Julius and Minnie’s only daughter, Rose, married Joseph Pach, younger brother of her sister-in-law Fannie, Leo’s wife.

By 1910, Julius had moved in with Leo and Fannie in Washington, DC; he was now working as a confections merchant. Leo was working as the assistant sealer of weights for the District of Columbia. Sylvester and his wife Bessie and daughter Minnie were also still living in DC, where Sylvester was working as a car builder for the Washington Railway Company. Moretto and his wife Annie and son Arthur were in DC as well where Moretto continued to work as a cabinet maker.

Although her father and three brothers were still living in DC in 1910, Rose Schoenthal and her husband Joseph Pach were living in Uniontown, Alabama, where Joseph owned a retail clothing and shoe business. I wondered what had taken them there. In 1910, the population of Uniontown was about 1,800, a 75% increase over its population in 1900, so something must have drawn all those new residents to the town. I found this insight in the Encyclopedia of Alabama website:

The area remained tied to the agricultural economy after the war. In 1897, the Uniontown Cotton Oil Company was established in the town, one of the first facilities of its kind in the state and one of the first industrial businesses in Perry County; it manufactured cotton seed oil and cotton seed meal. By 1900, the town had cotton gins, cotton warehouses, and a cotton mill. The city also had electricity and telephone services by this time. Less than two decades later, however, Uniontown began to lose population as more people moved off of plantations because of the boll weevil’s ruinous effect on the cotton crop, among other factors. The town remains largely dependent on agricultural activities, including livestock farming, in the surrounding area. –

I guess that Joseph Pach saw a town that was experiencing a population and economic boom and decided to start a business there. But it was over 800 miles from DC, and it must have been quite an adjustment for a young couple who were both born and raised in that larger city.

English: Co-Nita Manor within the Uniontown Historic District in Uniontown, Alabama. The district is on the National Register of Historic Places. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

In 1911, Leo Schoenthal and his superior, Colonel W.C. Haskell made the news for their investigation of fraud by ice dealers in DC who were “short weighting” customers; when some customers filed complaints with the Department of Weights and Measures, the dealers thereafter refused to sell to them. There was some discussion of criminal prosecution of the dealers. Here is a headline from an article in the Washington Herald of July 19, 1911 (p. 12):

According to the 1914 directory for Washington, DC, Julius and his three sons were still living in that city that year. Julius was still living with Leo and was working as a driver. Leo was the assistant superintendent for weights and measures. Sylvester’s occupation was listed as “Mach,” which I assume means machinist. Moretto was now working as an assistant superintendent for the Life Insurance Company of Virginia. (There was also a Hilda Schoenthal working as a bookkeeper and living on the same block as Leo and Julius; I believe she was the daughter of Henry Schoenthal, brother of Julius. But more on that in a later post.)

![Title : Washington, District of Columbia, City Directory, 1914 Source Information Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/schoenthals-in-1914-dc-directory.jpg?w=584)

Title : Washington, District of Columbia, City Directory, 1914

Source Information

Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

Passenger Manifest for Julius Schoethal and Rose Schoenthal Pach 1914

Year: 1914; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: T715, 1897-1957; Microfilm Roll: Roll 2368; Line: 1; Page Number: 96

It was after this trip that Julius reported that Americans were being well treated by the Germans and that in Berlin the government was closing down hotels that overcharged Americans. I found it quite interesting that Julius, who had by that time lived in the US for over forty years, still seemed to feel some loyalty to his birth country. I wonder how he felt once the US went to war against Germany a few years later.

The family made the newspaper again in 1916 when Leo and his wife Fannie celebrated their 15th wedding anniversary:

When the US entered World War I, all three of Julius Schoenthal’s sons registered for the draft. Leo was now the chief inspector for the District of Columbia; Sylvester was a car repairmen for the Washington & Southern Railroad Company; and Moretto was still an insurance agent for the Insurance Company of Virginia. Their brother-in-law Joseph Pach registered in Uniontown, Alabama, describing himself as a merchant. It does not appear, however, that any of them served in the war.

Sylvester and his wife Bessie, who had married in 1905, had not had any children listed on the 1910 census, but by 1920 they had two daughters: Margaret, born in 1914, and Helen, born in 1918. Leo’s daughter Minnie and Moretto’s son Arthur were teenagers by then. Rose and Joseph did not have any children, as far as I can tell.

On March 2, 1919, Julius Schoenthal died in Uniontown, Alabama; he must have been visiting his daughter Rose when he died. He was 74 years old and was buried at Washington Hebrew Cemetery in DC, where his wife Minnie had been buried 20 years earlier.

Julius had lived an interesting life, serving in the Germany army and then the US army after immigrating, and then seeking a position in the US government after that service. He must have felt proud to be a US citizen and a veteran, yet he was accused of being an anarchist in 1888. That obviously hurt him enough that he sued for libel; also, I have to wonder how he felt after repeatedly having his requests for increased pension payments denied.

He lost his wife at a relatively young age and never remarried. He had four children, three sons who lived close by throughout his life and a daughter who moved over 800 miles away. But when he died, he was with his daughter in Alabama, not his sons in DC. He worked as a shoemaker, a book salesman, and a seller of confections. He had many family members living in Pennsylvania, but I can find no indication that he had much contact with them after moving to Washington, DC., except for his niece Hilda living down the street in 1910.

As for his children, the three sons were all still living in DC in 1920, all still working at the same occupations. Rose and her husband Joseph were still in Uniontown, Alabama. At the time he died, Julius had four grandchildren: Arthur, Minnie, Helen, and Margaret Schoenthal, all living in Washington, DC.

More about his descendants in a subsequent post.

What a life, starting in the village of Sielen! And amazing the amount of data one can find in the National Archives. Often this is more difficult in Germany, and of course other partes of Europe, where so much destruction took many files away for ever….

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Dorothee! Yes, he did have quite an interesting life. I love being able to tell these stories. I just wish I could find out more about what he was really thinking and feeling!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What detail!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! For me, it’s all about the details. I love finding the story behind the names and dates.

LikeLike

I wonder if Catarrh would lead to asthma, which would have been debilitating in those days?

LikeLike

That’s an interesting question. I am hoping to get some insights from my medical consultant, i.e., my brother. I will let you know.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another fantastic piece of research Amy. You are bringing your ancestors to life so vividly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Su. Hope all is okay with you.

LikeLike

Hi Amy. Yes; all well (but very busy) here. I’m really glad your research seems to be progressing so well. It’s fascinating for me to read your posts because our family histories are so different and I’m learning a lot that I otherwise would probably never know. Cheers, Su.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad all is well! I do miss your family history blog posts, but now I will add the other one. I have learned a lot from you, so I look forward to your return to genealogy blogging!! Thanks for the kind words. 🙂

LikeLike

Have you changed your blog name to Zimmerbitch? I am looking to make sure I haven’t been missing posts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Amy. No; I have two blogs. I have been very negligent of my family history blog lately because I haven’t had time to do any research. ZimmerBitch is easier to keep posting to because it’s more photo-based. Sorry for the confusion. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: My Great-grandfather Comes to America: The Schoenthals in Western Pennsylvania 1880-1890 « Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Those Who Left Western Pennsylvania: The Schoenthals 1880-1900 « Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: My Great-great-uncle Henry: The Real Man Revealed « Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Henry Schoenthal: His Final Years and His Legacy « Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: The Goat, the Photographer, and the Daughter: The Children of Julius Schoenthal, Part I « Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Passover 2016: The Exodus | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey