Passover Seder Plate (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

As we approach the first night of Passover on Monday evening, I am feeling a bit overwhelmed, as I usually am this time of year. There is the cleaning, shopping, cooking, and all the other details that go into preparing the house for Passover and for the seder. I am also feeling torn because there are so many things I want to do in connection with my research and the blog. I have lots of photos to scan and post, both from my Brotman relatives and my Rosenzweig relatives, stories that need to be written, documents to request, people to contact. But I do not have time. So while the kugel is baking and before I start turning over the dishes and pots and pans for the holiday, I thought I’d take a few minutes to ponder what Passover means to me this year.

Passover was once my favorite holiday of the year. I loved the seder because as a child, it was my only formal exposure to Jewish history and Jewish rituals. I grew up in a secular home. We did not belong to a synagogue, I did not go to Hebrew school, and there were no bar or bat mitzvahs celebrated in our family when we were children. It was just fine with me, but I was also very curious about what it meant to be Jewish. Passover gave me a taste of what being Jewish meant and could mean. My Uncle Phil, my Aunt Elaine’s husband, had grown up in a traditional Jewish home, and although he was not terribly religious either, he wanted to have a seder.

So every year we had a seder, first only at my aunt’s house, and then my mother started doing a second seder at our house. My uncle, the only one who knew Hebrew, would chant all the blessings and sing all the songs, and the rest we would read in English from the Haggadah for the American Family (not Maxwell House). I was enchanted—I loved the music, the stories and all the rituals. I looked forward to it every year.

As an adult, I began my own exploration of what it means to be Jewish. I married a man from a traditional family, and he wanted to keep the traditions and rituals that were part of his childhood. I also wanted to learn more and do more. I took classes, I read, I got involved with the synagogue, and over time the Jewish holidays and rituals and prayers and services became second nature to me and provided me with meaning and comfort and joy.

Passover has become just one small part of my Jewish life and identity now, and over time, it has lost its magic. It no longer is my favorite holiday of the year. The matzoh gives me indigestion, the chore of changing the dishes and pots and pans has become tiresome, and the seder is so familiar that it no longer feels fresh and new and exciting.

If I look at it through my grandson’s eyes, I can feel some of that old excitement, but he is still too young to ask questions or to understand the stories. He just likes the songs and looking for the afikomen and being with his family, which is more than enough for now. This picture, one of my favorite pictures ever, captures some of that feeling. From generation to generation, traditions are being preserved.

L’dor v’dor Harvey and Nate

But this Passover I will try to take the time to think about things a little differently. I will think not just about Moses and the Israelites crossing the Red Sea and going from slavery to freedom. I will think about all my maternal ancestors who made their own Exodus by leaving poverty and oppression and prejudice and war in Romania and Galicia to come to the place where they hoped to find streets lined with gold.

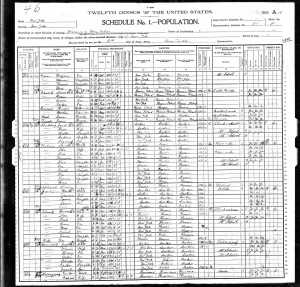

I will think of my grandfather Isadore, the first Goldschlager to come, leading the way for his father, his mother, his sister and his brother. I will think of how he traveled under his brother David’s name to escape from the army and come to America.

I will think of his aunt, Zusi Rosenzweig, who met him at the boat at Ellis Island. I will think of his uncle Gustave Rosenzweig, who was the first Rosenzweig to come to the United States back in about 1888, with his wife Gussie and infant daughter Lillie, a man who stood up for his extended family on several occasions. And I will think of his aunt Tillie Rosenzweig Strolowitz, who came to the US with her husband and her children, who lost her husband shortly after they arrived in the US. I will remember how she took in my grandfather and his sister Betty when their father, Moritz, died, and their own mother and brother David had not yet arrived.

And I will think about my great-grandfather Joseph Brotman, who came here alone in about 1888 from Galicia, whose sons Abraham and David from his first marriage came next, and whose son Max as just a ten year old boy may have traveled to America all alone. I will think of Bessie, my great-grandmother for whom I am named, who brought two small children, Hyman and Tillie, on that same trip a few years later, and who had three more children with Joseph between 1891 when she arrived and 1901, when Joseph died. The first of those three children was my grandmother Gussie Brotman, who married my grandfather Isadore Goldschlager after he spotted her on Pacific Street while visiting his Rosenzweig cousins who lived there as well.

All of these brave people, like the Israelites in Egypt before them, pulled up their stakes, left their homes behind, carrying only what they could carry, to seek a better life. I don’t know how religious any of them were or whether they saw themselves as brave, as crossing a Red Sea of their own. But when I sit and listen to the blessings and the traditional Passover songs this year, I will focus on my grandson and see in him all the courage and determination his ancestors had to have so that he could be here, free to live as he wants to live and able to ask us, “Ma Nish Ta Na Ha Leila Ha Zeh?” Why is this night different?

Why is this night different from all other nights? It isn’t because we are free; it’s because on Passover we remember what it was like not to be free and to be grateful for the gifts of those who enabled us to be free.

Happy Passover to all, and thank you to all my Brotman, Goldschlager and Rosenzweig relatives for making this such an exciting journey for me.