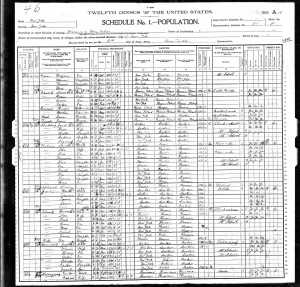

Without actual family memories, whether orally passed down or written in letters or diaries or memoirs, one thing that I cannot find through my research alone is any real sense of the personalities of the people I am researching. I can draw inferences at best, but usually not even that. So I cannot tell what kind of relationships these ancestors had with their children, their spouses, their parents, their siblings. I can try and put myself in their shoes, but what do I really know about what it was like to raise children a hundred or more years ago?

So when I think about the men in these families, I have no clue what kind of fathers they were. Were they at all engaged in the lives of their children? Did they have any role in child raising or child care? Certainly Hart Levy Cohen brought his children into his business as a general dealer, and Jacob brought his children into the pawnbroker business. But beyond that business relationship, all I can do is speculate about what kind of fathers these men were.

In my own life, I did not know my paternal grandfather at all since he died six years before I was born; my maternal grandfather died before I turned five, and although I have some sense memory of him, there are no specific stories or memories I can describe. I know that my mother and her siblings loved him dearly and that he was a smart, funny and strong-willed man who had the courage to walk out of Romania as a teenager and the determination and strength to come to the US alone and make a life for himself and his family. And that he was an incredible tease. But I didn’t know him long enough to think of him as a model for what a father should be.

My idea therefore of what a father is and should be was first defined by my own father. My father is a highly intelligent, sensitive, creative and loving person whose top priority has always been our family. He was way ahead of time in the 1950s and 1960s as a father who was actively involved in parenting. Because for most of my childhood and all of my adolescence he worked as an architect either in our house or in his studio attached to our house, he was much more available and accessible than most of the fathers of my friends at that time. When my mother started working out of the home when I was in junior high school, it was my father who greeted me when I got home from school and sat with me while I had my milk and cookies. He was and still is always interested in the details of my life.

He was also way ahead of his time in believing that girls as well as boys should fulfill their full academic potential. When I did not want to take physics in high school, he told me I was selling myself short and that physics was something I would regret not learning. I didn’t listen, and although I don’t regret taking the extra history course I took instead, he was right that it probably was more important to understand physics than I thought it would be when I was sixteen. Throughout high school, college, law school, and my career, my father along with my mother have always supported and encouraged me to learn, to work hard, and to find courses and work that would give me joy and satisfaction, and they still do. They also taught me to put family first.

The second significant father in my life is my husband Harvey. It was in many ways appropriate that my wedding day in 1976 was also Father’s Day because the man I married that day is truly the most devoted father of our children I ever could have imagined. He also has always put his family first, ahead of his career or anything else. He was and is my full partner in all parenting responsibilities, diaper to diaper, scraped knee to scraped knee, broken heart to broken heart. My girls knew to call Daddy, not Mommy, in the middle of the night because he was the one who had the patience to cope with upset stomachs or bad dreams at 2 am. He will drive any distance, pay any price, spend any amount of time, in order to help his children or me. Our happiness is the key to his own happiness.

Finally, I’d like to recognize one more father who is a big part of my life, my son-in-law. He is an incredibly devoted father to my two grandsons, including the new baby just over a week old. His face lights up with joy whenever he looks at his two sons. His love for them is so apparent. I know that he will be a wonderful role model for Nate and for Remy so that someday they also will be devoted and loving fathers, following in the footsteps of their father, their grandfather, and their great-grandfather.

Happy Father’s Day to the three of them and to all the other wonderful fathers out there!

By the way, did you notice that all three have beards?