As I’ve learned about the numerous members of my Seligmann family who were killed during the Holocaust, one of the questions that has bothered me was whether or not their American relatives were aware of what was going on in Germany. This, of course, is part of the larger question of what Americans, Jewish or not, knew about Hitler and his plans to murder the world’s entire Jewish population. Certainly people were aware of the anti-Semitic laws and practices, of Kristallnacht, of some violence against Jews, but to what extent were they aware of the seriousness, the severity of the situation, of the plans for genocide? We all know stories of immigrants who were denied entry, including full ships turned away from American ports. Historians have written about the failure of the Roosevelt Administration to respond to pleas for help from those who were very much aware of what was happening in Germany and elsewhere in Europe.

But what did my own family know? Did my Seligman relatives here in the US know what was happening to their cousins in Germany? In 1935 when the Nuremberg Laws were enacted in Germany, depriving Jews of their citizenship and imposing many other restrictions on their lives and livelihoods, both my great-grandmother Eva Seligman Cohen and her younger brother James Seligman, my great-great-uncle, were still alive (their youngest brother Arthur had died in 1933). Did they even know they had cousins living in Germany? Were they in touch with them? Did they know what was going on there?

To some extent those questions now have some answers, thanks to a series of letters from and to Fred Michel sent to me by his children. Fred Michel’s grandfather August Seligmann was the younger brother of Bernard Seligman, the father of Eva and James and my great-great-grandfather. Fred was thus the first cousin once removed of my great-grandmother and her brother. I wrote previously that in Fred Michel’s citizenship application he had identified James Seligman of Santa Fe as his sponsor for immigrating to the United States in 1937. Fred’s children have some letters written by James Seligman regarding the immigration of his German cousin that shed some light on my questions.

The earliest letter in this particular collection is one from James Seligman to George G. Harburger of Metropolitan Life Insurance in New York City, dated December 22, 1936. In this letter, James was writing in response to a letter from Mr. Harburger regarding a letter that had been sent from Frankfort, Germany, to Bernard and August Seligman, which an Ernest Rubel had delivered to Harburger. Ernest Rubel was the person whom Fred Michel later listed on his naturalization application as the person to whom he had been coming when he arrived in the US.

Courtesy of the Leo Baeck Institute

https://archive.org/stream/ilsefritzmichelf005#page/n30/mode/1up

James requested that the letter be sent to him, as he was the son of Bernard Seligman. There follows a German translation of the same letter. I wonder whether James knew German or whether he had someone else do this translation for him.

The next letter in the file is from James Seligman to Fred Michel. (Note that James addresses the letter to Fritz, which was Fred’s real name before he changed it after immigrating.) The letter is dated January 25, 1937, and in it James first described the American Seligmans—his father Bernard, his two uncles, Sigmund and Adolf, and his brother Arthur, all of whom had passed away by 1937, and then mentioned that only he and his sister were still living. His sister, of course, was my great-grandmother Eva.

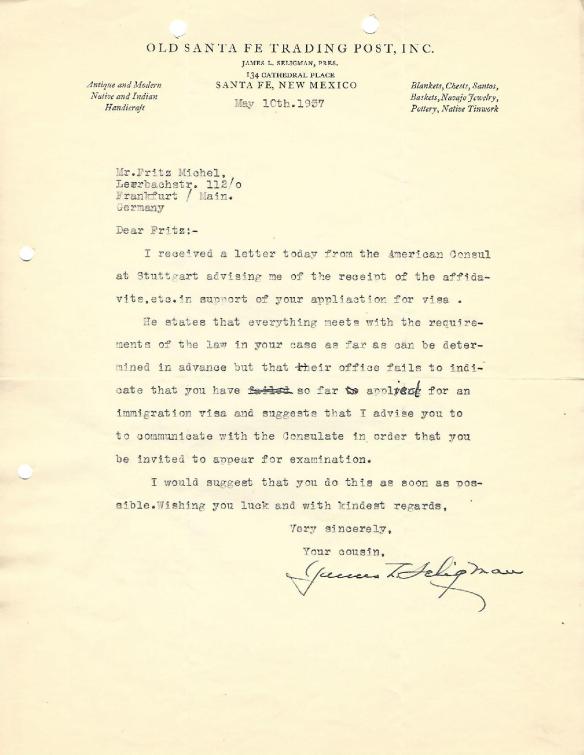

James then addressed the purpose of Fred’s letter to him: his desire to immigrate to the United States. James warned Fred about the unemployment situation in the US, although recognized that Fred had a friend in the US who could help him. Fred must have inquired about a possible job in Santa Fe with James, to which James replied, “As regards a job in this city, this would be out of the question as I only have a very small business myself with only one employee and which is all it will stand.” By 1930, James Seligman was no longer affiliated with Seligman Brothers and had formed his own business, the Old Santa Fe Trading Post, which must have been the business to which he was referring in his letter to Fred Michel. Fred might very well have been taken aback by this flat-out refusal to help him find a job in Santa Fe. But James agreed to help Fred by sending an affidavit in support of his immigration and closed by wishing him the best and expressing hopes to meet him some day.

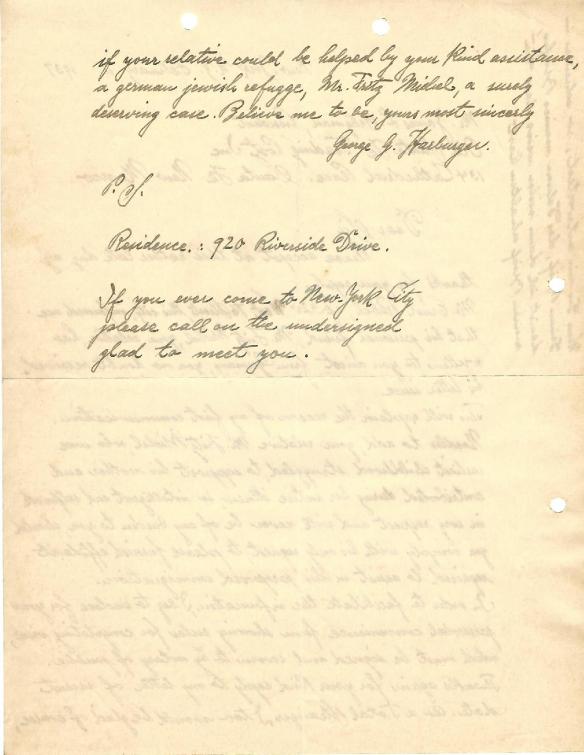

On February 11, 1937, George Harburger wrote to James Seligman to persuade him to help. It appears from the letter that Ernest Rubel, Fred’s personal friend, had contacted Harburger to ask him to contact James for help. I am not sure of the various connections there, but George described Fred as someone who had supported his mother all his life and as an intelligent and self-made man who would “never be a burden” to James and then instructed him how to submit an affidavit in support of Fred’s immigration.

James then wrote to Fred again on May 10, 1937, advising Fred that the American Consulate had received James’ affidavit and that all was in order, but that they had not yet received an application from Fred himself. James advised him to do so “as soon as possible.”

Then there was a letter in German which I could not translate, but which the kind people in the Germany Genealogy group on Facebook helped me with:

Here is the translation of this letter from Fred Michel to the US Consulate on May 1, 1937:

Subject: Pledge from Mr James Seligman,321 Hilside Ave., Santa Fe,

for Fritz Michel, Leerbachstreet 112/o at Moritz (means in the apartment of Moritz), Frankfurt/Main

To the consulate general of the USA

Dear Mr Consul General!

Attached I’m sending you the missing papers for your examination.

Obtaining the papers I had to learn that my landlord didn’t register me for 3 month (from March until May 1933). Please find the reason for that in the authentication attached. Also you can find in attached transcript of my certificate where I was working during that time. If you wish I can bring the original paper with me. The County Department of Bingen /Rh. ( at the Rhine), where I complained about my certificate of good conduct four times, just sent me the information that the required paper was given to post it to Stuttgart on May 3 to your address.

I own a proper passport.

If I won’t hear from you, I’ll assume that my papers are in order.

Yours respectfully

Attachments:

4 passport pictures, 2 birth certificates

4 certificates of good conduct

1 transcript of certificate

Reading this letter after I’d had it translated made me angry; it so clearly reflects how difficult some in Germany were making it for Fred to be able to leave, but also how difficult the US was making it for him to arrive.

From other documents we know that Fred Michel was finally allowed to immigrate and arrived in the US on September 24, 1937. On October 10, 1937, his cousin James wrote to him again, welcoming him to the United States. Fred must have enclosed a photograph in his letter to James telling him of his arrival because James referred to it as indicating the Fred must have encountered bad weather while crossing the ocean to America. Fred also must have told James that he had landed a job and was living with friends.

I found the next paragraph of this letter very telling. James warned Fred that it might take some time to adjust to his new country and then said, “How anyone can live in Germany under that man Hitler I cannot understand but suppose they cannot get away from it all.” What did he know about Hitler as of September 1937? Were his feelings shared by Americans in general? And isn’t it also revealing that James, the son of a man who had left Germany behind about 80 years earlier, could not imagine why others were not also leaving Germany as his father and Fred Michel had done? Would James have found it so easy to leave his homeland if the shoes were on the other feet?

James then thanked Fred for a gift he had sent him—a writing set—but says Fred should have saved his money until he “could afford it better.” Was this insulting to Fred as patronizing? Or did he see it as an older cousin’s concern? James closed by saying, “Let me hear from you from time to time and let me know how you are getting along and what kind of work you are doing as I will always want to know.” Although I read this as genuine interest and concern, it is not at all clear to me that Fred and James maintained much or any future contact. Fred’s children seemed to believe that they did not.

In any case, James died on December 15, 1940, just three years after Fred’s arrival in the US. Among Fred’s papers was an obituary for his cousin James that he must have saved for many years. I had not seen this obituary before, and I do not know in what paper it was published or the date and page. I will not transcribe its content here, but will add it to the post I wrote quite a while back about James Seligman.

The next letter in this file was written many years later. On October 9, 1975, Fred wrote the following letter to Mrs. Randolph Seligman of Albuquerque, New Mexico, thinking she might perhaps be a relative, and identifying his own background and his connection to James Seligman of Santa Fe.

Of greatest interest to me in this letter is this short reference to my great-grandmother: “Once I met Eva Seligman in Philly.” My great-grandmother died in October 1939, just two years after Fred arrived. My father was living with her at the time that she likely met Fred Michel. He doesn’t remember him, though he said the name was familiar, but probably from reading it on the blog. From what I have learned about my great-grandmother, she was a warm and welcoming person who had several times taken in relatives in need. I wish I knew more about her meeting with her German-born cousin Fred Michel.

Mrs. Randolph Seligman responded shortly thereafter that although she was not a relative of the Santa Fe Seligmans, the Santa Fe phone directory listed a William Seligman and a Jake Seligman living in Santa Fe. [These were the sons of Adolph Seligman, about whom I wrote here.] She said they had once met William, known as Willie, years before in his clothing store in Sante Fe. In November 1975, she wrote again, commenting that it was strange that the two New Mexico families did not know each other, but attributed that to the fact that “they married non-Jews and became affiliated with the Episcopal Church.” Near the end of her letters she spoke of plans to visit with Willie Seligman in Santa Fe and identified him as a relative of Arthur and James Seligman. Fred responded to her on January 5, 1976, expressing his delight that she had written to him again and filling her in on his family.

But within what is otherwise a newsy and cheery letter are two sad passages. After referring to some relatives he remembered from Germany, Fred wrote, “As I write these notes I am amazed how much I know about my family when one considered I left “home” when I was 18, never to return. Finally, in 1972 while in Europe I contacted some survivors. It was an emotional experience we never forget. Some I haven’t seen since Hitler came to power.”[1] For me, this is a powerful statement in its own understated way. Here was a man who had left everything behind yet even he is surprised by how much he still remembered of his family and his past.

The other disturbing passage in this letter is in the following paragraph where Fred wrote about the travel plans he and Ilse had made in 1974, including to Santa Fe, where Fred had relatives, and to Georgia, where Ilse had relatives. Fred wrote that they had discarded those plans “as Ilse reasoned that in spite of her writing after arriving here, she never received an answer and the same goes for my relatives in S.F. [Santa Fe].” How sad that so many years later Fred and Ilse both still felt hurt by the fact that their American relatives had not stayed in touch with them.

I don’t know how to reconcile that with the welcoming letters that Fred received from James, but obviously there were some hard feelings there, whether justified or not. I just find it very sad that two people who had lost so much felt so abandoned by their American relatives.

So what did those American Seligman relatives know by 1937 when Fred was trying to escape from Germany? They knew that they had German relatives, they knew that things were bad for Jews with Hitler in power, and they knew that there were at least some family members who wanted to leave Germany and come to the United States. Did they do enough? Of course, in retrospect nothing anyone did was enough, given the outcome of the Holocaust. And it is hard to know sitting here today what more any one individual could or should have done. Certainly James did what he was asked to do and helped Fred immigrate. Could he have given him a job? Could he or any of the Seligmans have reached out to these newly arrived cousins in a more committed way? I don’t know, and I can’t judge. But I do judge our government which closed its eyes and its ears for political and other reasons while thousands and eventually millions were killed.

[1] I don’t know why Fred wrote that he was 18 when he left home. The US records all give his birth year as 1906, and he came to the US in 1937 when he was 31, not 18. Perhaps he is referring to leaving home in a more specific way, not leaving Germany.

I have sometimes wondered why it seems so difficult for people to reach out and help those whose lives are being systematically destroyed. Nazi Germany is of course a prime example, but today’s world is equally full of the persecuted. I think that although we may “know” that others — distant relatives for example — are suffering, on a day to day basis, we are largely focused on our own lives. When James told Fred he had no job for him, it was probably in the context of his own problems paying the bills, feeding his family, keeping his business afloat. With hindsight, we can say that no matter how bad things seemed in Santa Fe, they were infinitely worse in Germany. But I don’t think humans work like that; we focus on the immediate, the specific, our own lives. Our emotions are the measuring stick against which others are compared. Media researchers found a long time ago that the further away from us (physically/culturally) an event takes place, the larger it has to be to be “newsworthy.” So a car crash in our neighbourhood with one fatality = a fatal bus crash in the next state = a plane crash in another part of our country = a huge earthquake in a distant part of the world. It’s appalling; but possibly a coping mechanism to stop us being overwhelmed by the amount of suffering and our limited ability to make a difference.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for this thoughtful comment. You are so right about human nature. I don’t judge James or Fred. We all can only do our best. But our governments should take more responsibility for protecting others in need.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I absolutely agree. If we adopt compassion as a civic duty, it becomes, I think, easier to practice it at a personal level too. I am so tired of the government here celebrating greed and selfishness. We have one in five children living poverty, going to school hungry and failing in their learning. We are wrecking our future, but our government will not even acknowledge that such poverty exists.

LikeLike

Our system is so broken that even when the government acknowledges a problem, they can’t agree on how to address it. So frustrating and depressing.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Amy, you bring up some thought-provoking questions. It’s so hard to look back and interpret responses. Even if people knew things were bad they couldn’t conceptualizer what was going on as we, with our hindsight, can. I’m sure people were worried about being saddled with responsibilities and damaging their own lifestyles. We do the same or we would be opening our homes to refugees from ISIS etc. it’s Roosevelt who let down a lot of people. It was his job to help. He had inside info.

LikeLike

I agree with you completely. That’s why I can’t judge what any individual did or didn’t know. But the government was being informed and chose not to take any actions that would create political damage at home. Very cowardly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is such a powerful post.

My grandparents tried in earnest to get people out of Germany during this time. They were able to get many out but not everyone. For example, in one case which I am currently researching, a relative by marriage, a judge with influence who could have helped, refused to intervene and help bring three family members to the US. They perished.

He knew what was going on but his heart was hardened.

LikeLiked by 1 person

These stories are so heartbreaking. It is just too awful to imagine how many lives could have been saved if only…. And how the world might today be a different place if those people and all their potential descendants had survived.

LikeLiked by 1 person