I just finished watching a video called “Galicia Mon Amour.” It is a recording of a conversation between Daniel Mendelsohn and Leon Wieseltier. Mendelsohn’s book, The Lost, which I read a number of years ago, is one of the most moving books I’ve read; in it he recounts his journey to find out what happened to members of his family who had not left Galicia before the Holocaust. It is beautifully written, well-researched, and deeply tragic. I read it long before I started doing my own genealogical research, but it likely was one of the sources of inspiration for my journey.[1]

Leon Wieseltier’s book Kaddish is also excellent, but I have to admit much of it was a bit too scholarly and dry for my taste, except for the parts where he reflects on his own family and experiences. I admit to skimming a lot of the more academic parts of the book.

At any rate, when I saw a recommendation for the video on the digest I receive daily from Gesher Galicia, I decided to try and make the time to watch the video. (It’s about two hours long.) You can find a link to the video here.

In the video Mendelsohn interviews Wieseltier about his recent trip to Galicia. (The interview takes place in January, 2007; Wieseltier’s trip was in 2006.) Both Mendelsohn and Wieseltier had family that came from eastern Galicia in what is now Ukraine from towns near the city of Lviv, known by the Jews as Lemberg. Both had taken trips back to the region to research and visit the places where their relatives had lived. Although Mendelsohn’s direct ancestors had immigrated to the United States before the Holocaust like ours did, he had many relatives who remained behind about whom he had known very little.[2] Wieseltier’s parents, on the other hand, were Holocaust survivors and came to the United States after World War II. All the rest of his family was killed in the Holocaust.

One audience member asked at the end of the interview whether there were differences between those who were grandchildren of immigrants and those who were children of Holocaust survivors. Were the survivors from the wealthier families who saw no reason to leave in the 19th century and the earlier immigrants from the poorer families who had no reason to stay? Although Wieseltier dismissed this as an overgeneralization, which I am sure it is, it nevertheless is an interesting sociological question. Remembering Margoshes’ memoirs and the fact that there were so many wealthy Jews, I thought that it made some sense that only those who had nothing to lose would have taken the risk of leaving the world they knew. This may suggest that Joseph and Bessie were not among the wealthier segments of the Galician Jewish community.

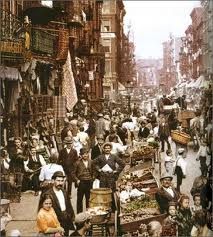

Wieseltier described his own family as being among the more prosperous, educated and aristocratic clans in their area and confirmed the impression left by Margoshes that the Jewish world in Galicia was very diverse and that there were many who were wealthy, well-educated, and sophisticated. He described Cracow as the “Jerusalem of the North” and the Galitzianers as the princes of the Jewish world. Mendelsohn concurred, saying that although there was also a lot of poverty, there was a large bourgeoisie and a large wealthy class. He said that Emperor Franz Joseph, who was the head of the Austro-Hungarian Empire from 1848 until 1916, was admired and even loved by the Jews for his enlightened leadership and treatment of the Jewish citizens, also described in Margoshes’ memoirs.

One observation that I found particularly interesting was Mendelsohn’s comment that he always thought of Jews as living in tenements until he went to Galicia. He believed that Jews, wherever they lived, lived urban lives, and he was surprised by how wrong he was when he saw the rural areas where they had lived in Galicia. He described the countryside as beautiful—with mountain, streams, rivers. Wieseltier used the word “paradise” to describe it.

A lot of their conversation focused on the reasons to make a trip to Galicia. Both said quite emphatically that this is not a place to go for typical tourist reasons; for Mendelsohn it was partly to find out what happened there and to visit the places where his family had lived. Wieseltier said he went not only out of grief, but also out of pride. He talked movingly of standing where his mother had once stood and leaving a copy of his book in the empty field as a symbol of Jewish survival. Both talked about the absence of Jewish life there now and how the Polish people themselves realize how much has been lost by the destruction of the Jews and their culture. Wieseltier said that you won’t find Jewish life there so you must bring your Judaism with you if you go.

There is also discussion of the Holocaust, of the camps, of anti-Semitism, but overall the theme was more about remembering the world that was there in a realistic and accurate way and cherishing that culture and the people. Wieseltier himself is quite skeptical of genealogy (“It’s amazing how much you can’t learn from genealogy.”). Although Mendelsohn obviously values genealogical research highly, he did not really push Wieseltier to elaborate on this point. I think, however, that Wieseltier was expressing some doubts about all those who, like me, are trying to trace some names and dates to make a connection, perhaps without any purpose or perspective. He said that our parents and grandparents were ours “by luck,” just as the fact that we have two legs or brown eyes, and that what is more important is who we are ourselves and what we do with our lives. I think that that is an important perspective for me to remember as I continue to look for our family in Galicia.

[1] We were fortunate enough to hear Mendelsohn read from and talk about the book many years back when it was first published. That made his story even that much more personal.

[2][2][2] I am sure that that is true for the Brotman family as well, although I do not know specifically of any family members who died in the Holocaust.

Related articles

- A World Apart, part 5: Relationships between Jews and non-Jews in Galicia (brotmanblog.wordpress.com)

- A World Apart: Conclusion (brotmanblog.wordpress.com)

- A World Apart, part 3: Marriage in Galicia (brotmanblog.wordpress.com)

- A World Apart, part 4: The Rich and the Poor in Galicia (brotmanblog.wordpress.com)