Before my break, I wrote about the six children that my three-times great-uncle Abraham Goldsmith had with his first wife, Cecelia Adler, before she died from a stroke at age 35 in 1874: Milton, Hilda, Edwin, Rose, Emily, and Estelle. Two years after Cecelia’s death, Abraham married Frances Spanier, with whom he had another four children: Alfred (1877), Bertha (1878), Alice (1880), and Louis (1882). The age span from Abraham’s oldest child Milton, born in 1861, to his youngest child Louis was 21 years. The next set of posts will focus on the four children of Abraham and Frances. This first post tells the sad story of Alfred’s first marriage.

Abraham and Frances’ first child, Alfred Francis Goldsmith, was born on August 11, 1877, in Philadelphia.1 According to his obituary, he attended the University of Pennsylvania.2 In 1900, he was living with his parents in Philadelphia and working as a salesman.3

Five years later he married Beatrice R. Miller, who was also a Philadelphia native, born there to William Miller and Fannie Stein on March 29, 1882. Her parents were born in Pennsylvania, and her father was in the clothing business. 4 Alfred and Beatrice obtained their marriage license in Delaware on September 16, 1905, and Alfred’s occupation on the marriage register was listed as “wholesale.”5

I then had trouble locating Alfred and Beatrice together on any subsequent record. I found an Alfred F. Goldsmith listed in the 1906 Camden, New Jersey, directory, but no occupation was given. Then in 1908, Alfred F. Goldsmith is listed in the Philadelphia directory, residing at 1437 Edgewood; again, no occupation was given. In 1911 there is an Alfred F. Goldsmith listed as a jeweler, living at 1521 N. 28th Street in Philadelphia. Despite having these two Philadelphia addresses, I could not find Alfred on the 1910 census. The first address was not on the census records at all, and the second did not have anyone named Goldsmith listed at that address. Alfred was not listed in the Philadelphia or Camden directories for 1907, 1909, or 1910.6

I was more than a bit perplexed, so I turned to newspapers.com to search for more information about Alfred and Beatrice, and what I found was a story of star-crossed lovers—or so it would appear. Judge for yourself:

Love’s Sweet Dream Ended

Young Philadelphia Couple Married Here Recently

Now Wife Wants Divorce

Was A Romantic Elopement

Divorce is the sequel of the romantic elopement of Miss Beatrice R. Miller and Alfred F. Goldsmith of Philadelphia, to this city about nine weeks ago, when they were quietly wedded by the Rev. W.N. Sherwood at the residence of the Rev. G.L. Wolfe. After the couple were married they made the officiating minister promise them he would not divulge their marriage, and he refused at the time to talk about the elopement.

Coerced Into Marriage

In her petition for a divorce Mrs. Goldsmith alleges that she was coerced and intimidated into marrying her husband. She is 23 years of age and a daughter of William Miller, one of the lessees of the Girard Avenue and Forepaugh Theatres, and resides with her parents at No. 1712 North Eighteenth street, in Philadelphia.

Goldsmith is a tobacco and cigar dealer and resides at No. 3326 North Fifteenth street. He denies his wife’s allegations and contends that parental influence is keeping her from him. The full nature of her charges have not been disclosed.

The young couple’s elopement to Wilmington followed an alleged secret engagement of three years, during which time Goldsmith was not allowed to call at the Miller home. They corresponded regularly, however, and frequently met at the homes of mutual friends. In the meantime Miss Miller became engaged to another suitor, a friend of her father, but meeting Goldsmith at a friend’s house on September 16, they came to this city that afternoon, and were married by the Rev. Sherwood. They returned to Philadelphia immediately after the ceremony had been performed, and then went to Haddonfield, N.J., where they remained until the following Tuesday. They then went to the Miller home, but Goldsmith said he was ordered out by Mr. Miller, although the bride was permitted to remain. He has since had a short interview with his bride, but she would not leave her home and accompany him.

What do you think? Was Beatrice coerced into marrying Alfred, or were her parents just opposed to the marriage and determined to end it?

Here’s my read of the situation, taking into consideration that I am a romantic and also that Alfred was my cousin, so I might be somewhat biased. I think Beatrice was intimidated by her parents into ending the marriage. After all, she was not a child; she was 23, not a particularly young age for women to marry at that time. They had been engaged for three years before the elopement. Obviously Alfred waited patiently and was not rushing her into marriage. And she continued to see him even after her parents had prohibited him from coming to their house. On September 16, she crossed a state line with him to get secretly married. There does not appear to be any claim that he forcibly took her to Wilmington, Delaware. After all, she agreed to meet him at a friend’s house, presumably for that purpose.

Of course, I don’t have all the facts, but that is my take on this story. And I can’t help but wonder why Beatrice’s parents were so vehemently opposed to her relationship with Alfred. This was not a case of an interfaith marriage; the Millers were Jewish as were the Goldsmiths. Alfred certainly came from a well-established family; his father had been a successful business owner in Philadelphia. So what was the problem? Did Beatrice’s family not approve of his livelihood?

I wondered whether the Millers were just overprotective and did not want their daughter leaving home at age 23. But their second daughter, Fay, was a year younger than Beatrice and married when she was 23 in 1906.7 Somehow that marriage survived—although I did notice that Fay and her husband moved to New York not too long after getting married.

I am also amazed that a personal story like this made the front page of the Wilmington newspaper in 1905. We complain today about our lack of privacy, but at least we can control some of what appears about us on social media. What was newsworthy about this sad story of a broken marriage? Sure, it’s a juicy story for selling newspapers, but these were private citizens, not celebrities or public figures.

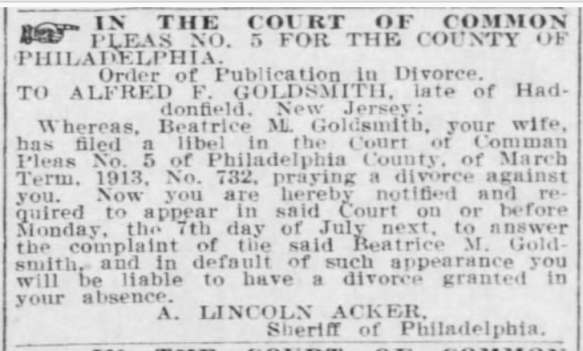

What is even more peculiar about this story is that Beatrice and Alfred were not in fact divorced for another eight years. In June 1913, the Philadelphia newspapers ran this legal notice over the course of several weeks:

And then finally on December 16, 1913, their divorce was finalized.8 What was going on in those eight years? Had Beatrice ultimately defied her parents and stayed with Alfred? Or had her parents eventually relented and allowed her to reunite with her husband? Or had there just been a very long separation?

I can’t find either Alfred or Beatrice on the 1910 census or in any directories between 1905 and 1913 aside from those mentioned above (where Alfred is not listed with Beatrice, though that itself is not necessarily an indication that she was not living with him). They are not listed living with their parents or siblings either. They do not appear in any other newspaper articles that I can find. Had they run off and changed their names? Had they left the country? I don’t know, and I don’t know where else to look for clues. If you have any suggestions, please let me know.

Beatrice did eventually remarry, though not for quite a long time. I could not find her on the 1920 census, but in 1922 she was listed as Beatrice Miller in the Ocean City, New Jersey directory.9 By April 23, 1923, she was married to Harry F. Stanton, according to this ship manifest:

Ship manifest for Beatrice and Harry Stanton, lines 23 and 24, Year: 1923; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: T715, 1897-1957; Microfilm Roll: Roll 3276; Line: 1; Page Number: 29 Source Information Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957

Harry had also been listed in the 1922 Ocean City, New Jersey directory.10 In 1910, he’d been living in Ocean City, working in the real estate business,11 and I located numerous real estate advertisements under Harry F. Stanton’s name in the Philadelphia newspapers. Harry was fourteen years older than Beatrice and had been married before; he does not appear to have been Jewish. I wonder if Beatrice’s family was happier with this match. If Beatrice married Harry in about 1922-1923, she was about 40 and he was about 54 at the time. They remained married until Harry’s death in 1945.12

And what happened to Alfred after the divorce from Beatrice in 1913? His story will continue in my next post.

- Pennsylvania, Philadelphia City Births, 1860-1906,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:V1MS-C1M : 10 March 2018), Alfred Goldsmith, 11 Aug 1877; citing bk 1877 p 157, Department of Records; FHL microfilm 1,289,318. ↩

- “A.F. Goldsmith, 66, Book Dealer, Dies,” The New York Times, July 30, 1947, p. 17. ↩

- Goldsmith family, 1940 US Census, Census Place: Philadelphia Ward 12, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Enumeration District: 0208. Ancestry.com. 1900 United States Federal Census. ↩

- Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007. SSN 198367783. ↩

- Ancestry.com. Delaware, Marriage Records, 1806-1933; Collection and Roll: Register of Marriages – 3. ↩

- Philadelphia City Directories, 1907-1911; Camden City Directory, 1906; Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995. ↩

- Marriage of Fay Miller and Irving Wolf, 1906, Ancestry.com. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Marriage Index, 1885-1951; Marriage License Number: 205685. ↩

- Philadelphia Inquirer, December 16, 1913, p. 11. ↩

- Ocean City, New Jersey City Directory, 1922, Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995. ↩

- Ocean City, New Jersey City Directory, 1922, Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995. ↩

- Harry Stanton, 1910 US Census, Census Place: Ocean City Ward 2, Cape May, New Jersey; Roll: T624_870; Page: 17A; Enumeration District: 0093; FHL microfilm: 1374883. Ancestry.com. 1910 United States Federal Census ↩

- Pennsylvania Historic and Museum Commission; Pennsylvania, USA; Certificate Number Range: 054601-057000. Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1966. Certificate Number: 56258. ↩

![Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/jennie-stern-death-certificate-jpg.jpg?w=584&h=439)

![Robert Steel Kann death certificate Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/robert-kann-death-cert.jpg?w=584&h=541)