English: Ellis Island’s Immigrant Landing Station, February 24, 1905. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

One of my favorite documents to locate is a ship manifest listing one of our ancestors as a passenger, bringing them from Europe to America. I have read and seen enough about these ships and the hardships that the passengers endured to know that these were not pleasant cruises across the Atlantic Ocean. People suffered from disease, malnutrition, terrible hygienic conditions, and frequently even death. Yet I tend to romanticize these journeys, despite the facts. I imagine how frightened but also how excited these travelers must have been, thrown together with other people from all different countries and of all different backgrounds, all of whom were dreaming of a better life in the United States. The stories told by ship manifests I’ve found do much to break down that romantic ideal.

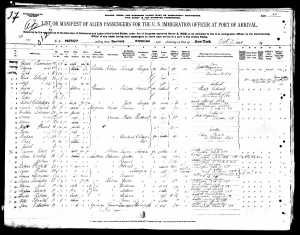

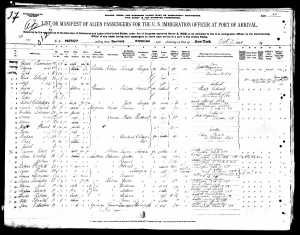

I was only able to find two ship manifests for the Brotman immigrants. The first exciting find was the manifest for the Obdam, the ship that brought Bessie, Hyman and Tillie to New York in January, 1891. Their names were listed as Pessel, Chaim and Temy Brodmann. One column lists how many pieces of luggage each passenger brought, and for Bessie, Hyman and Tillie, they brought only two pieces of luggage. Imagine fitting the clothing of three people plus any other possessions you wanted to keep with you into just two pieces of luggage. When we go away for a weekend, we often need more than that for just two of us. Hyman was only 8, Tillie 6, and somehow they endured this long voyage at sea with their mother. When I fast-forward to how American they became as adults, I find it remarkable.

The Obdam 1891

The only other ship manifest I located for the Brotman family is one I believe is for Max, but cannot tell for sure. It lists a Moshe (?) Brodmann as a ten year old boy, traveling with one bag, on a ship called the City of Chicago in 1890. This very well could be Max, but there is no other Brodmann or anyone else with a similar name traveling with him. If I have a hard time imagining Hyman and Tillie coming with their mother, it is really unfathomable to imagine a ten year old boy traveling alone across the ocean. None of the names above or on the page following his sound like possible relatives, friends or even neighbors since for the most part they are listed as coming from Russia, not Austria. If that is in fact our Max, I imagine that this must have been an incredible experience—frightening, even horrifying, and lonely. Perhaps an experience like that explains how these children then endured the working and living conditions they found in the United States. They had already survived much worse.

I’ve had no luck yet locating a manifest that includes Joseph or Abraham Brotman, but I will keep looking.

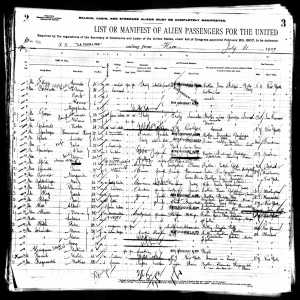

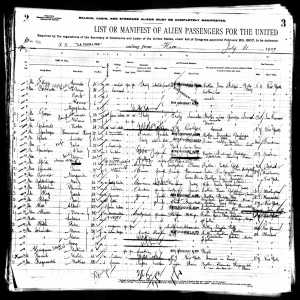

On the Goldschlager side, I’ve had more success. I have found a ship manifest for Moritz, Gisella, David and Betty, each of whom came separately, but nothing for my grandfather Isadore. These manifests also tell interesting and some heart-breaking stories. David came in 1904 on the Patricia, which departed out of Hamburg. (Perhaps like his brother, David also walked out of Romania to get to Hamburg.) This manifest contains far more information than the two above. First, it asks for information about who paid for the ticket and the name, address and relationship of any relative or friend the passenger was joining at their destination. David said his uncle paid his passage and that he was going to join that uncle in New York. From what I can decipher, it looks like the uncle’s name was Moishe Minz.

David Goldschlager ship manifest

I have searched many times and ways to figure out who this person was and how he was an uncle to David. Was he a brother-in-law of Moritz or of Gisella/Gittel/Gussie? Since his last name is neither Goldschlager or Rosensweig (Gisella’s maiden name), I assume he is not a brother. Or perhaps he is a half-brother. Whoever he was, I cannot find him yet. I also find it puzzling that David listed this uncle and not his brother Isadore. Perhaps because Isadore himself was still just a minor, he would not have been a satisfactory person to list as the connection for David in the United States. The other interesting bit of information gleaned from this manifest is the amount of money David was carrying with him: six dollars. He was 16 years old, traveling alone, with six dollars to his name.

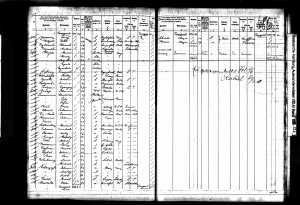

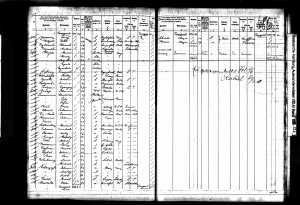

The next to arrive was Isadore and David’s father, Moritz. He arrived in August 1909 on the ship La Touraine out of Havre. His occupation is listed as a tailor, and his age as 46 years old. This manifest did not ask who you were meeting in the United States, but instead who you were leaving behind in your old place of residence. Moritz listed his wife, Gisella Goldschlager. So by August 1909, the three males in the family had emigrated from Iasi, and Gisella and her daughter Betty were left behind. This seems consistent with the pattern in the Brotman family: Joseph came first, then his two sons from his first marriage, and then his wife and younger children.

Moritz Goldschlager ship manifest

Betty’s arrival story is more complicated and very sad. On the ship manifest filed at Ellis Island, Betty had listed her father as the person she was joining in New York. Betty arrived in April 4, 1910, on the ship Kaiserin Auguste Victoria. However, she was detained at Ellis Island for a short time. On a document titled “Record of Detained Aliens,” the cause given for detention simply says “to father.”

Betty Goldschlager Detention of Aliens

According to his headstone, her father Moritz died on April 3, 1910, the day before Betty arrived on the Kaiserin August Victoria. It is hard to believe that her father died the day before she arrived, but if the records and headstone are accurate, that is what happened.

Moritz Goldschlager headstone

Betty must have been kept at Ellis Island until another person could meet her. On that form for detained aliens, she listed an aunt, Tillie Srulowitz, under “Disposition,” which I interpret to mean that Betty was released to her aunt on April 4 at 3 pm. (More about Tillie Srulowitz in my next post.)

This story breaks my heart. Moritz had only been in the United States since August, just eight months, when he died. He did not live to see his daughter or his wife again. He was only fifty years old. I don’t have his death certificate yet, but will see if I can obtain it and learn why he died. Imagine how Isadore and David must have felt—waiting four to five years to see their father, only to lose him eight months later. And imagine how Betty must have felt—coming to America, taking that awful voyage, only to be greeted with the news that her father had died just before she arrived.

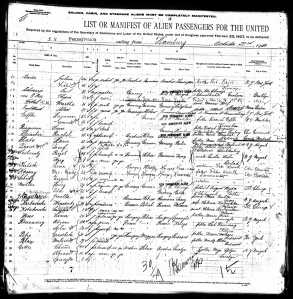

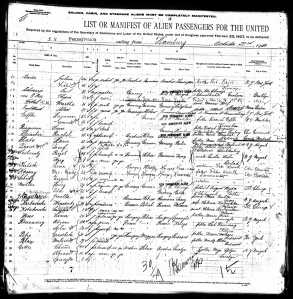

And finally, think about his wife Gisella. She arrived in NYC in November, 1910, seven months after her husband had died. Did she know what was awaiting her? She sailed on the ship Pennsylvania out of Hamburg; the ship manifest does not list who was waiting for her, only the name of someone who resided in her old home, a friend named Max Fischler.

Gisella Goldschlager ship manifest

But the record from Ellis Island indicates that she had expected to join her husband Morris Goldschlager, but was instead released to her son Isadore. I have no idea how immigrants communicated with their relatives back in Europe in those days or how quickly news could travel from place to place, but since the ship manifest indicates that the ship sailed from Hamburg on October 23, 1910, over six months after Moritz had died, Gisella must not have known that he had died, or why would she have listed him as the person receiving her in New York when she got to Ellis Island? It appears that Gisella did not know until she arrived in New York that her husband had died the previous April. It is heart-breaking to imagine what her reunion with her sons and daughter must have been like under those circumstances.

EDITED: Some of the facts in this post have been updated with subsequent research. See my post of January 22, 2014, entitled “Update: My Grandfather’s Arrival.” Also, this one.

English: Immigrants entering the United States through Ellis Island, the main immigrant entry facility of the United States from 1892 to 1954. Español: Inmigrantes entran a los Estados Unidos a traves de la Isla Ellis, el mayor lugar de entrada a los Estados Unidos entre 1892 y 1954. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)