Although I have completed as best I can the stories of five of the children of my great-great-grandparents Levi and Henriette (Hamberg) Schoenthal (Hannah, Amalie, Felix, Julius and Nathan), I still need to complete the stories of Henry, Simon, and, of course, my great-grandfather Isidore.[1] In addition, there were two siblings living in Germany whose stories I’ve yet to tell, Jakob and Rosalie. First, I want to return to Henry, the brother who led the way for the others.

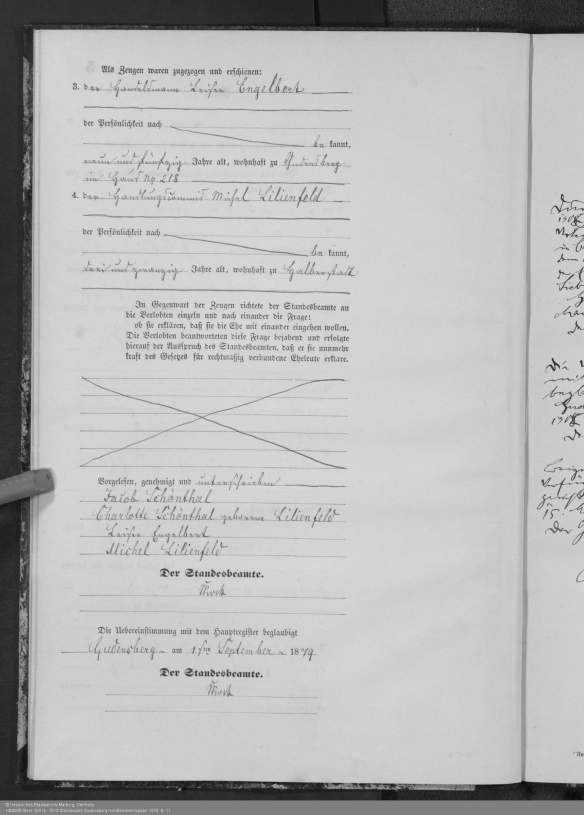

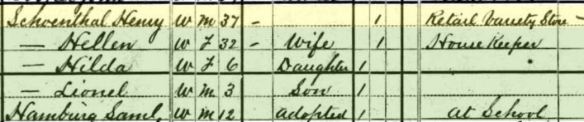

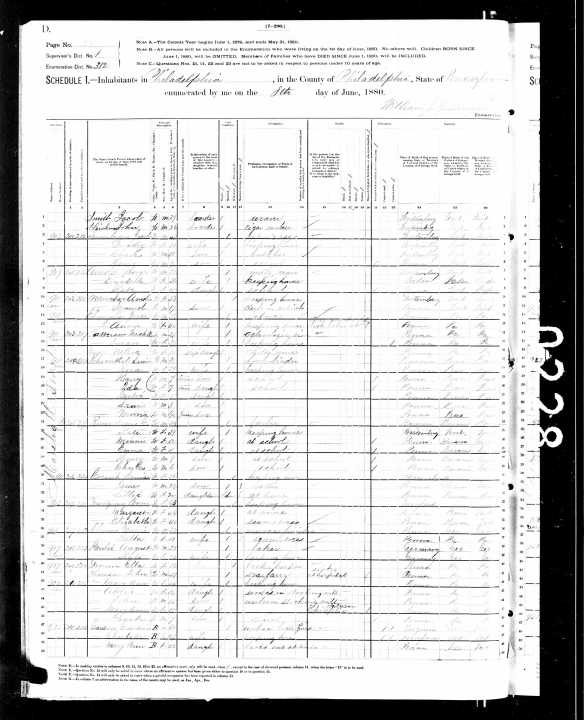

As I wrote here, after living for over 40 years in Washington, Pennsylvania, Henry Schoenthal moved with his wife Helen (nee Lilienfeld) to New York City in 1909 to be closer to their son Lionel. Lionel had moved to NYC to work as a china buyer, first working for one enterprise, but eventually working for Gimbels department store. Lionel was married to Irma (nee Silverman), and they had a daughter Florence, born on March 22, 1905.

In 1910, Henry and Helen’s other son Meyer had married Mary McKinnie, the daughter of a wealthy industrialist from Colorado. Meyer and Mary had met while Mary was a student at a girl’s boarding school, Washington Seminary, in Washington, Pennsylvania. After marrying, they were living in Los Angeles, and Meyer was working for an investment company.

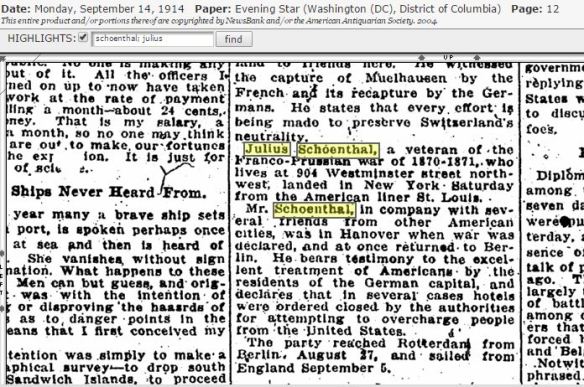

Hilda Schoenthal, Henry and Helen’s daughter, was working as a stenographer in Washington, DC, in 1911. She was living on the same street as her uncle Julius Schoenthal and cousin Leo Schoenthal, the 900 block of Westminster Avenue.

![1911 directory for Washington, DC Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/1911-dc-directory-hilda-and-other-schoenthals.jpg?w=584)

1911 directory for Washington, DC

Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

According to her obituary (see below), Hilda moved to DC to work for a patent attorney. In 1914, she was working as a bookkeeper for Karl P. McElroy, who appears to have been the patent attorney, as her brother Meyer later worked for him as well, as noted below in his obituary.

![1914 directory for Washington, DC Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/1914-dc-directory-schoenthals.jpg?w=584)

1914 directory for Washington, DC

Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

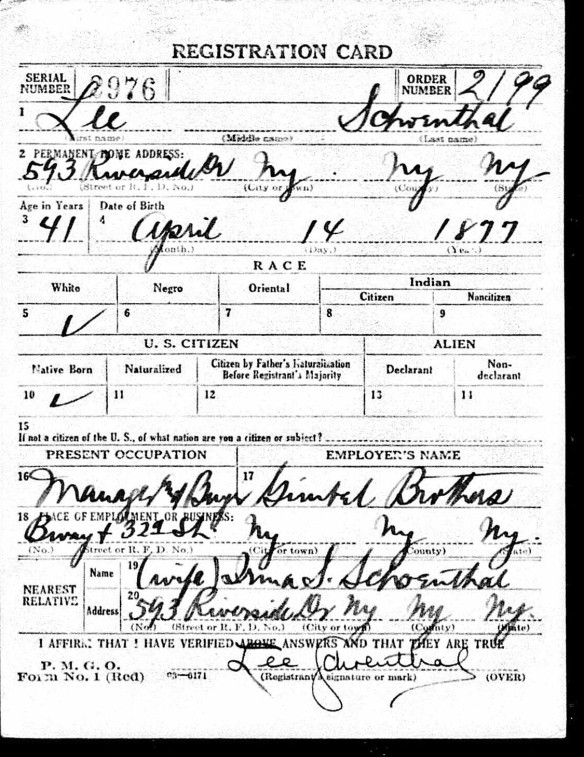

In 1915, Henry and Helen were still living with Lionel (called Lee on this census, as he often was in other documents and news articles), Irma, and Florence on Riverside Drive in New York City. Lee was still working as a buyer, and no one else was employed outside the home. Lee’s draft registration for World War II shows that in 1918 he was still working for Gimbels, living on Riverside Drive.

Lionel (Lee) Schoenthal World War I draft registration

Registration State: New York; Registration County: New York; Roll: 1786675; Draft Board: 141

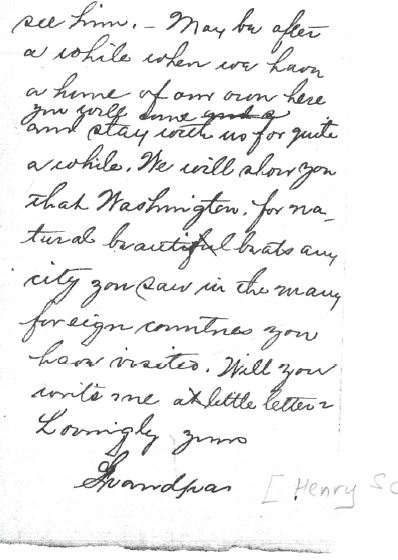

Thanks to the assistance of the Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh, I was able to obtain a copy of a letter that Henry Schoenthal wrote to his granddaughter Florence in December, 1918, when she was almost fourteen years old:

My darling Florence, I told you yesterday that I was mad at you, but I aint. Beg pardon, I mean I am not. I love you just as much as ever, but I would have been so happy if you had stayed a few days with us. Of course I will have to send word to President Wilson that you went home and that you could not come to see him. Maybe after a while when we have a home of our own here you will come and stay with us for quite a while. We will show you that Washington, for natural beauty, beats any city you saw in the many foreign countries you have visited. Will you write me a little letter? Lovingly yours, Grandpa.

I love the teasing tone of this sweet letter to his granddaughter; it shows yet another facet of this interesting great-great-uncle of mine. His diaries from his early years in Washington were all very serious, and the speech he gave on a return trip to Washington, PA, in 1912 revealed his spiritual and sentimental side. Here we get to see some of his sense of humor and the affection he felt for his only grandchild, Florence, who probably like most teenagers was anxious to get home to her friends rather than spend more time with her grandparents.

I was at first a bit confused as to where Henry was living when he wrote this letter. He refers to the natural beauty of Washington, but it’s not clear whether he is referring to Washington, PA, or Washington, DC. I concluded, however, that he meant DC because his daughter Hilda was living there and perhaps he and Helen were planning to relocate there. Also, the reference to seeing President Wilson makes no sense unless he and Helen were in DC.

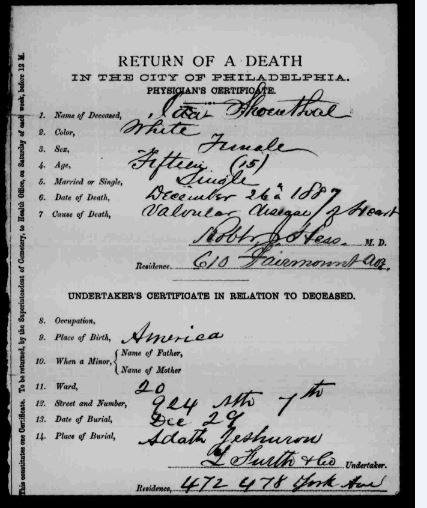

Not long after the writing of this letter, the Schoenthal family suffered a sad loss. Henry’s son Meyer was living with his wife Mary in Blythe, California, working as a lumber merchant, when he registered for the draft on September 12, 1918. Just three months later, Mary died on December 24, 1918. She was only 31 years old. They had been married for just eight years. There were no children.

On the 1920 census, Meyer is listed as a widow, living alone, and still working in the lumber business. He had moved from Blythe to Palo Verde, California.

If Henry and Helen Schoenthal did move to DC for a period of time, by 1920 they had returned to NYC and were again living with their son Lee and his family on Riverside Drive, according to the 1920 census record. Lee was still working as a buyer. Hilda Schoenthal, their daughter, was still living in Washington DC, but was now working as a law clerk for the patent attorneys, according to the 1920 census.

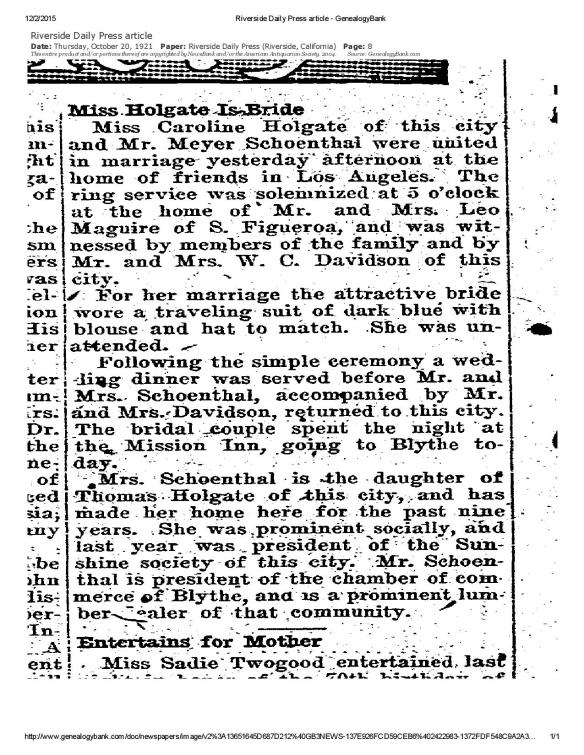

On October 19, 1921, Meyer L. Schoenthal married for a second time. His second wife was Caroline S. Holgate (sometimes spelled Carolyn). By that time Meyer was considered a “prominent lumber dealer” and was president of the Blythe, California, chamber of commerce; his new bride was also “prominent socially” and had been president of the Sunshine Society in Blythe.

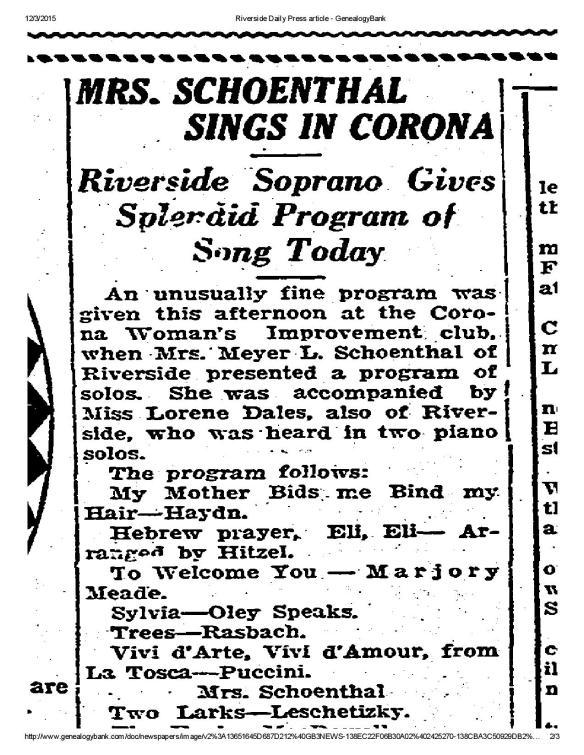

Caroline was also apparently a talented soprano, as I found numerous articles referring to her performances at various social events. Here’s just one example.

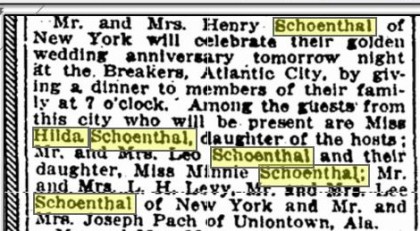

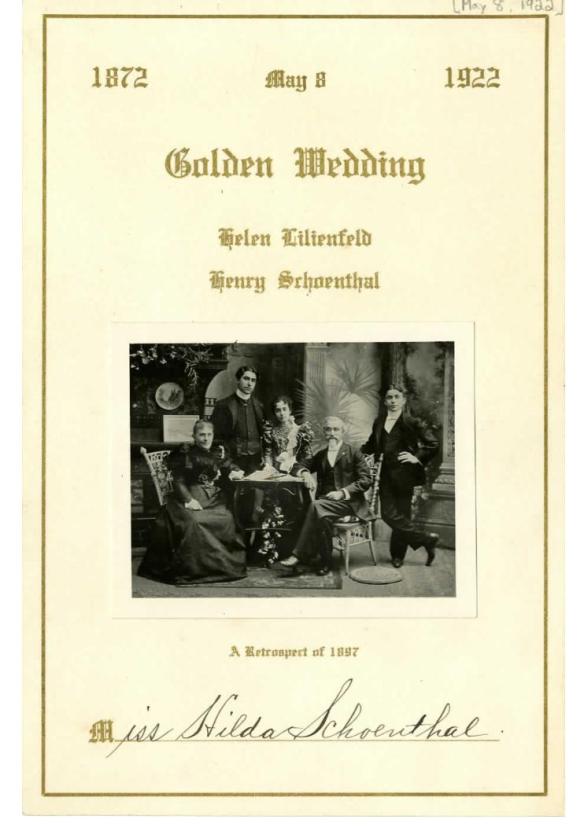

Perhaps she also sang at the celebration of the 50th wedding anniversary of her new in-laws, Henry and Helen Schoenthal, which took place on May 8, 1922, in Atlantic City, New Jersey, although they were not among the guests listed in this news item.

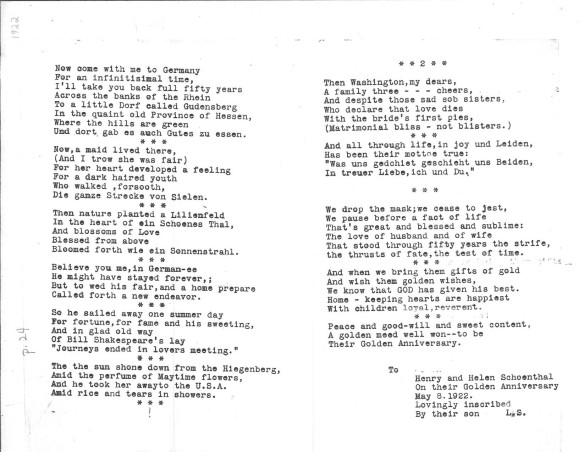

For that occasion, Lionel/Lee Schoenthal wrote these very loving lines of verse in honor of his parents:

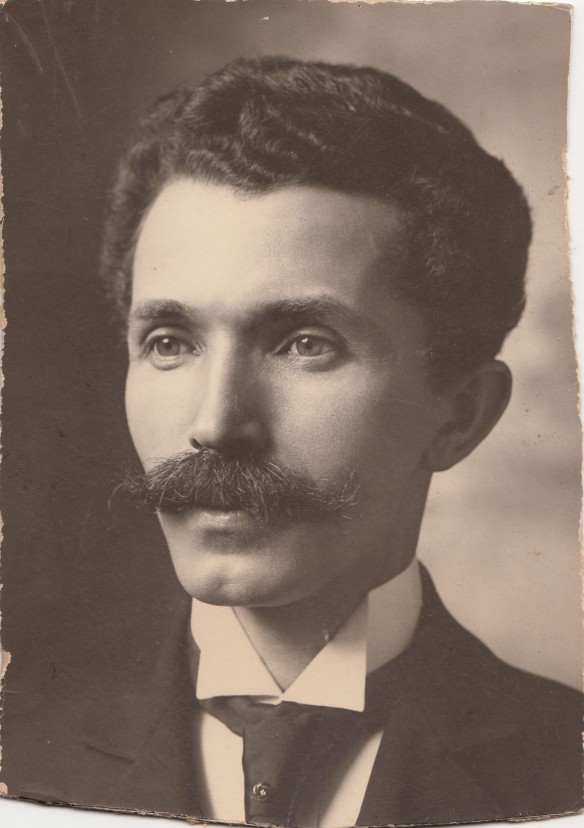

Lionel (Lee) Schoenthal 1922 passport photograph National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 – March 31, 1925; Roll #: 1829; Volume #: Roll 1829 – Certificates: 117226-117599, 09 Feb 1922-10 Feb 1922

(I haven’t transcribed the poem or translated the German lines here, but you can always click and zoom if you want to read it.)

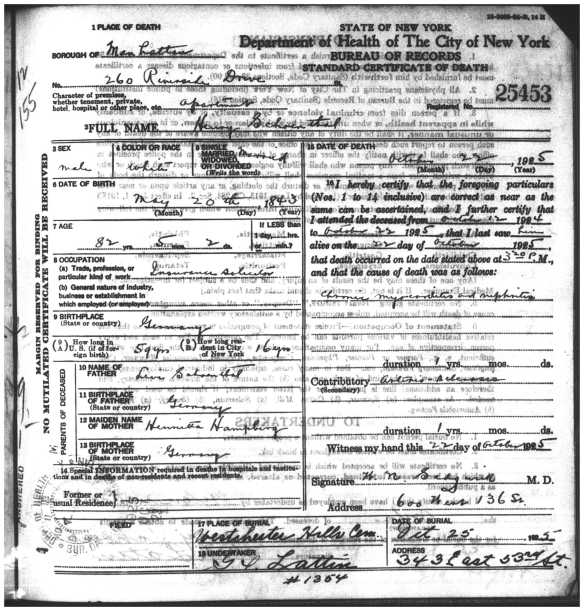

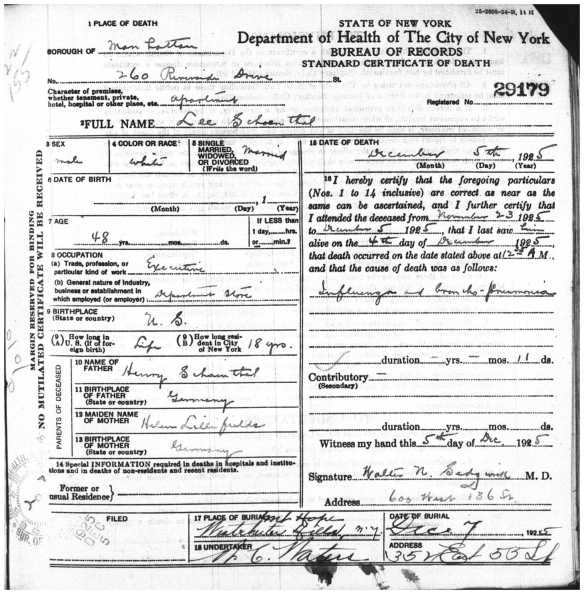

Sadly, three years later, the Schoenthal family lost both Henry and his son Lionel. Henry died on October 22, 1925, from heart and kidney disease. He was 82 years old and had lived a good and long life for a man of his generation. After training as a Jewish teacher and scholar in Germany, he had immigrated from Sielen, Germany, to Washington, Pennsylvania,the first of his siblings to do so . Later, he had brought his young bride Helen Lilienfeld from Gudensberg, Germany, to Pennsylvania, and they had raised three children together after losing one as a baby. In Washington, PA, he’d been a successful businessman and respected citizen. When his son Lionel moved to New York City, Henry and his wife Helen moved there also to be near his son and his only grandchild, Florence. He had lived there for the last sixteen years of his life, working for some of that time as an insurance salesman, as indicated on his death certificate. He was buried at Westchester Hills Cemetery in Hastings-on-Hudson, less than fifteen miles from where my parents are living. Perhaps one day I will pay him a visit.

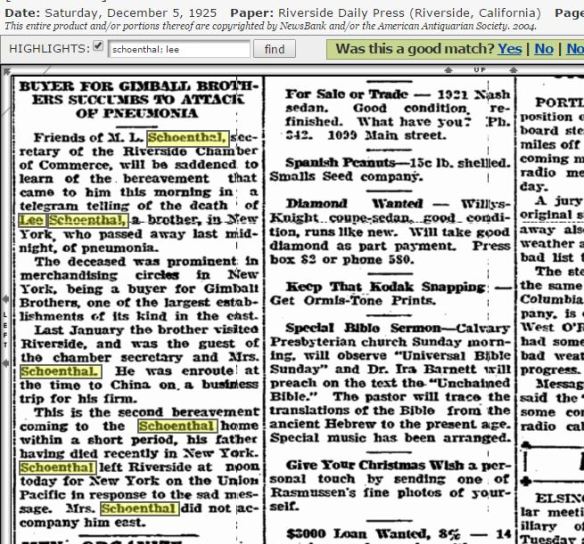

The family must have been in complete shock when Lee Schoenthal died of pneumonia on December 5, 1925, just six weeks after his father had died; Lee was only 48 years old, and his daughter Florence was only 20 years old when he died.

Here is part of a long and detailed obituary from the December 10, 1925 issue of The Pottery, Glass, and Brass Salesman (p. 153):

I will transcribe some of the content:

Lee Schoenthal, supervisor of the china, glassware and allied departments of Gimbel Brothers’ associated stores, passed away at his home in New York City early on Saturday morning, December 5, following an acute illness of two weeks. [There is then a detailed description of Lee’s poor health, referring to his dedication to his job and overwork as contributing factors to his death.] …

Lee Schoenthal was born in Washington, Pa., April 12, 1877. His father and mother, who were born in Germany, had come to this country some years before and Henry Schoenthal—Lee’s father—had built up a nice retail business in Washington. Lee attended the schools of his native town and then his parents, themselves highly cultured, made the effort to give their son a collegiate training, sending him to Washington and Jefferson College, located in Washington. During his college career he stood well in his classes and was particularly noted for his musical accomplishments, being leader of the college orchestra for several years. As a matter of fact, it is entirely possible that if he had devoted himself wholeheartedly to music instead of to commerce he might have become a musical celebrity. …

Some twenty years ago Mr. Schoenthal came to New York to “seek his fortune.” [Then follows a detailed description of Lee’s business career, first with the Siegel-Cooper Company and then with Gimbels.]…

Mr. Schoenthal, for a man of his comparative youth, probably developed more men as successful buyers of china and glassware than anyone else in the country. He had that rare gift of imparting knowledge and that quality of the really big man of business that he never feared to impart all information he could to those who worked with him. Modest to a degree, he could not help being conscious of his compelling influence and ability, so the thought never entered his mind that he might be jeopardizing his own position by teaching others all they could absorb from his store of knowledge and wisdom.

[The obituary then describes Lee’s interests outside of work, in particular his love of music, but also art and architecture.] Himself a deeply religious Jew of the modernist type, he could talk more familiarly of the history of the Catholic cathedrals and their adornments than many men of the Christian faith.

[Finally, the obituary described his family life: his happy marriage, his talented daughter, and his devotion to his parents, for whom he had provided a home for many years.]

The obituary thus focused not only on Lee’s distinguished business career, but also on his broad intellectual and cultural interests, his musical talents, and his religious and personal life. It described him as a “deeply religious Jew of the modernist type” and as a man devoted to his family. His family must have been very proud of him.

Both deaths were noted in Meyer Schoenthal’s home paper in Riverside, California:

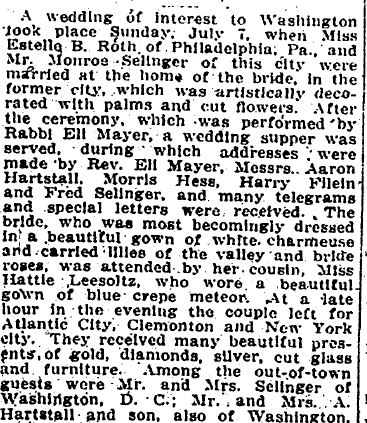

Two years later on October 19, 1927, Florence Schoenthal, the grandchild of Henry and Helen Schoenthal and daughter of Lee Schoenthal, married Verner Bickart Callomon in New York City. Verner Callomon was the son of a German Jewish immigrant, Bernhardt Callomon, who had settled in Pittsburgh and worked for Rodef Shalom synagogue there, the same synagogue to which Henry Schoenthal had once belonged. Verner was a doctor, and his career was described as follows by the Rauh Jewish Archives at the Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh:

Verner Callomon (1892-1977) graduated with honors from the University of Pennsylvania in 1915 with a degree in medicine. He served as a junior lieutenant in World War I and returned to Pittsburgh to practice internal medicine. He was a pulmonary disease specialist and researcher at Allegheny General Hospital and Montefiore Hospital for nearly 60 years and was the chief of medicine at both institutions at different times during his long career. His research contributed to changes in the treatment of pneumonia. He was known both for his professionalism and for his compassion. In order to visit weather-bound patients, he rowed down Liberty Avenue during the 1936 St. Patrick’s Day flood and secured an Army jeep during the November 1950 snowstorm.

As far as I can tell, Florence and Verner settled in Pittsburgh after they married since that is where Verner is listed in the 1929 directory for Pittsburgh and also were their first child was born in 1929.

(The Rauh website also includes links to several articles about the Callomon family. Of particular interest to me was the oral history interview with Jane Callomon, one of the children of Florence (Schoenthal) and Verner Callomon, on file at the University of Pittsburgh Library (“Pittsburgh and Beyond: The Experience of the Jewish Community,” National Council of Jewish Women, Pittsburgh Section, Oral History Collection at the University of Pittsburgh).)

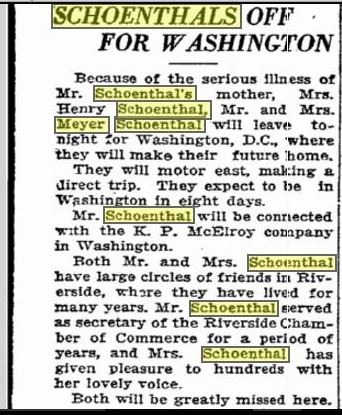

In 1927, following her husband’s death, Helen Lilienfeld Schoenthal moved to Washington, DC, from NYC to live with her daughter Hilda. They were living at 3532 Connecticut Avenue NW in 1927, and Hilda was still working for K.P. McElroy, now as a bookkeeper and notary public.

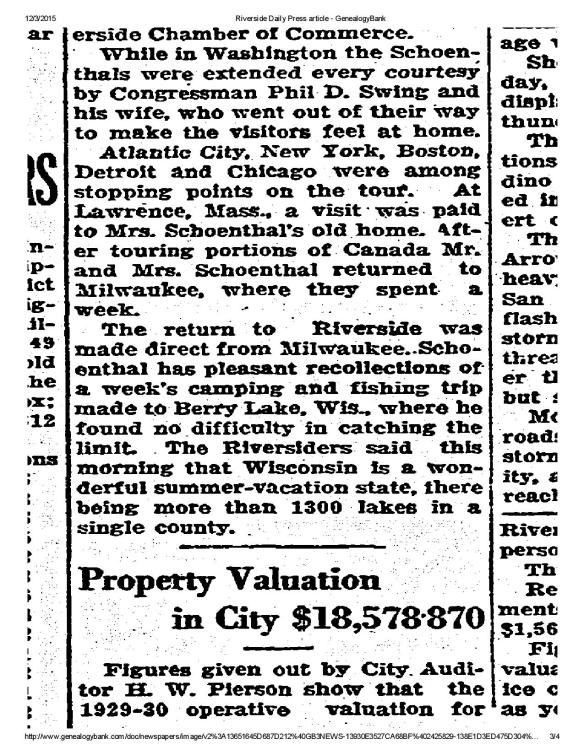

Meyer Schoenthal continued to prosper in California and was elected a vice-president of the California Association of Commercial Secretaries in 1928 (“Fresno Chosen Next Meeting Place California Commercial Secretaries,” Riverside Daily Press, January 14, 1928, p, 2) ; in 1929 he and his wife Caroline took an eleven-week trip to the East Coast, visiting not only his sister and mother in Washington, DC, but also his birthplace, Washington, PA, and many other locations.

Although Meyer and Caroline were still living in Riverside, California, on April 2, 1930, when the census was taken, by September, 1930, they had moved east permanently:

Note that Meyer was going to work for the same business that had long employed his sister Hilda, K.P. McElroy.

In 1930, Hilda and her mother were living in the Broadmoor Apartments at 3601 Connecticut Avenue. By 1932, Meyer and his wife had moved in with them, as listed in the 1932 directory for Washington, DC, and he and his wife were still living there with them in 1937. Both Hilda and Meyer were working for K.P. McElroy, Hilda as his personal secretary, Meyer as the office manager.

![Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/1937-dc-directory-for-schoenthals.jpg?w=584)

Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

In April 1930, Florence Schoenthal Callomon appeared in a production of C.B. Fernald’s “The Mask and the Face” at the Y Playhouse in New York City; a noted Shakespearean actor led the cast, B. Iden Payne. Florence was a woman of many talents, it appears. She also was an artist who had worked as an advertising illustrator for Gimbels before she married. I cannot find Verner or Florence on the 1930 census in either Pittsburgh or NYC, but regardless of where she was living, I am not sure how she pulled off appearing in this production since she had a one year old child at the time.

Florence Schoenthal Callomon http://www.jewishfamilieshistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/YM_WHA_Weekly_v4_no29_04041930_pp1_4.pdf

On October 10, 1937, the family matriarch Helen Lilienfeld Schoenthal died. She was almost 89 years old (despite the headline on her obituary, she was one month short of her 90th year). She was buried with her husband at Westchester Hills Cemetery:

From the second obituary in the Riverside Daily Press, it appears that Meyer and Caroline Schoenthal had by October 1937 moved to their own place at 2700 Rodman Road in DC.

By 1940, Meyer and Caroline were living as lodgers in a home with thirteen other residents at 2700 Quebec Street; Meyer, 56 years old, was still working for the patent firm. His sister Hilda, now 65, was also still working at the patent firm and still living at 3601 Connecticut Avenue.

Florence Schoenthal Callomon and her husband Verner Callomon were living in Pittsburgh in 1940; Verner was a doctor in private practice. They now had two children.

Hilda Schoenthal died on June 6, 1962. She was 87 years old.

According to her obituary, sometime after 1940 she had left K.P. McElroy, her longtime employer, to work for Gulf Oil in their patent department. If times had been different, I have a feeling that Hilda would have become a patent lawyer herself. On the personal side, she seems to have had an active social life with many friends and relatives with whom she traveled and socialized, according to several news items from the society pages of the Washington Evening Star. Hilda was buried at Westchester Hills Cemetery, where her parents were interred.

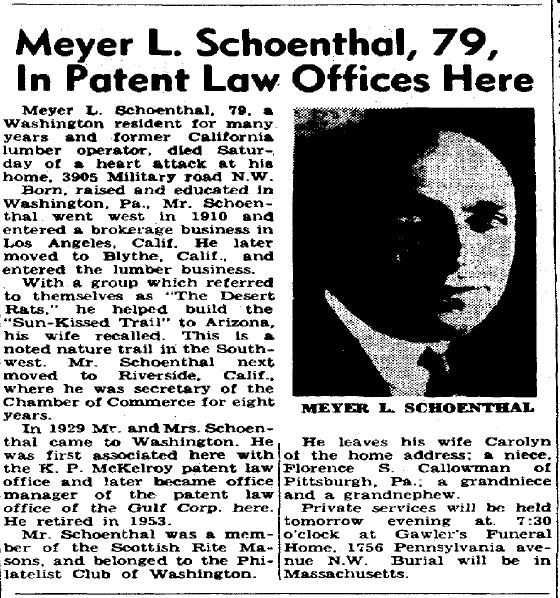

Less than a year later, on February 16, 1963, the last remaining child of Henry and Helen Schoenthal, Meyer Lilienfeld Schoenthal, died. He was 79.

He died from a heart attack; unlike his sister Hilda and his parents, he was buried in Massachusetts, where his wife Carolyn/Caroline was born. She outlived him by 20 years, dying in January, 1983, when she was 84.

The obituary revealed a few things that I otherwise would not have known about Meyer: that he had helped build a “noted nature trail” in the Southwest and that he was a philatelist (stamp collector). It is interesting that, like his sister Hilda, he had gone to work at Gulf Oil Corporation after working for many years for K.P. McElroy.

The only surviving descendants of Henry Schoenthal after 1963 were his granddaughter Florence Schoenthal Callomon and her children. Florence died in 1994 when she was 89 years old. According to the Rauh Archives, she had been “a member and officer of many Pittsburgh and Pennsylvania organizations, including the Western Pennsylvania Women’s Golf Association, the Women’s Committee of The Carnegie Museum of Art, the Pittsburgh Symphony Association and the Rodef Shalom Sisterhood, among others.” From the oral history interview their daughter Jane referenced above, it is clear that both Florence and Verner were involved in many aspects of the Pittsburgh community.

Thus, Henry and Helen Schoenthal left quite a legacy. Their three children all were successful in their careers and ventured far beyond little Washington, PA, where they’d been born: Hilda to DC, Lionel/Lee to NYC, and Meyer to California and then to DC. Things came almost full circle when Florence Schoenthal Callomon, their granddaughter, returned to western Pennsylvania where her German immigrant grandparents had settled and where her father and aunt and uncle had been born and raised. Pittsburgh is where Florence and her husband Verner raised their children and where those children stayed as even as adults.

I’d imagine that my great-great-uncle Henry would have been very proud of his three children and his granddaughter for all that they accomplished. Even in 1912 he knew how blessed he had been in his life when he addressed his friends in Washington, PA, and told them:

I gratefully acknowledge that God has been very gracious unto me and that he has blessed me beyond my merits.

I feel very blessed to have been able to learn so much about my great-great-uncle Henry and his family, and I hope someday to be able to connect with his descendants.

[1] Two of twelve children of Levi Schoenthal and Henriette Hamberg did not survive to adulthood. Of the other ten, eight immigrated to the United States, including my great-grandfather. One of the siblings remained in Germany, Jakob, and Rosalie returned to Germany to marry after a few years in the US.

![Title : Washington, District of Columbia, City Directory, 1914 Source Information Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/schoenthals-in-1914-dc-directory.jpg?w=584)