Although I have no memory of meeting Aunt Tillie, I heard her name all the time when I was growing up. (I don’t know which spelling she preferred; sometimes it is Tilly, sometimes Tillie. I have used both spellings throughout the blog.) She was very close to my grandmother Gussie, and my mother and her sister and brother adored her. She was described to me as a lot of fun: vivacious, outgoing, funny and loving. It seems she was the one who provided a lot of the happy experiences for my mother and her siblings growing up.

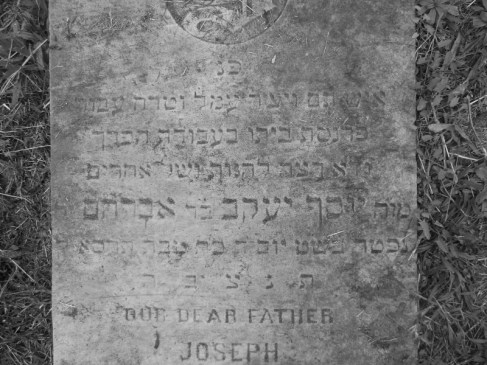

Like my grandmother, she had a tough life. She was born in 1884 and came to the US with Bessie and Chaim when she was 6 or 7 (census reports are in conflict; some say 1890, some say 1891). In 1900 when she was sixteen, she was living on Ridge Street with her parents, her brother Hyman, and her two little sisters, Gussie, who was five, and Frieda, was three. When her father Joseph died a year later, my guess is that Tillie must have become a second parent to Gussie, Frieda and the infant Sam.

In 1905 when she was 22, Tillie married Aaron Ressler. At the time she was still living on Ridge Street with her mother and siblings. Aaron was 26 at the time and was also living in the Lower East Side. By 1910, Tillie and Aaron had three sons, Leo, Joseph, and Harry, all under five. They were living at 94 Broadway in Brooklyn, where they owned a grocery store at 100 Broadway. In addition, Gussie had moved in with them, choosing to live with Tillie instead of moving in with Bessie after she had married Phillip Moskowitz. (Bessie and Phillip were still living on the Lower East Side in 1910, so moving to Brooklyn must have been a big deal for twelve year old Gussie.) Gussie helped take care of the boys while Aaron and Tillie worked in the store. Family lore has it that my grandfather spotted my grandmother while she was sitting in the window of Tillie and Aaron’s store.

Life must have seemed pretty good for the Ressler family in 1910. By 1918, however, things had changed. On Aaron’s draft registration form of that year, he reported that he was not employed and was suffering from locomotor ataxia, a condition that causes pain and loss of muscle control and movements. The 1920 census did report that Aaron worked at a grocery store, although it also said he worked at home. They no longer lived on Broadway, but on Ralph Avenue in Brooklyn. Aaron died six years later in February, 1926, leaving behind Tillie and three sons aged 20, 19, and 17.

Tillie continued to run the grocery store for some time after Aaron died. I cannot find any record of Tillie and her two younger sons in the 1930 census, but in 1940 she was living on the Grand Concourse in the Bronx with Joe and Harry (Leo had married Mildred and moved to Connecticut by then). According to the census, she had also lived at this same address in 1935, so at some point Tillie had left Brooklyn as a widow with two almost grown sons and moved all the way to the Bronx. She never remarried and died at age 72 in 1956 after suffering from painful arthritis. My mother remembers that she was treated with cortisone, perhaps excessively, and ended up dying in a public hospital on Welfare Island in NYC, where my grandmother would go to see her every week.

I don’t know why she moved to the Bronx, perhaps to make a fresh start. My mother remembers that Aunt Tillie lived in an apartment on the then-glamorous Grand Concourse with her two adult sons, Joe and Harry. I don’t know how she supported herself after Aaron died, but somehow she did. My mother was born after Aaron died, and so she only knew Tillie as a widow, yet she remembers Tillie as a happy, upbeat person who would bring my mother baked goods (and once a large easel) that she carried on the subway from the Bronx to Brooklyn on her weekly trips. Tillie was the one who held the family together—the one who encouraged my aunt Elaine to go stay with Leo and Mildred in Connecticut to broaden her horizons, who took my mother to baseball games, who could occasionally get my shy grandmother to socialize. When my sister was born in 1955, Tillie brought treats not only for my mother, but also for the other new mothers who were sharing the same hospital room. She was a woman who was born in Europe, but spoke English like an American, who brought up three sons, took care of her sisters and brothers, and was one of the most positive influences on my mother and her siblings. She was strong and positive despite all the hardships she had faced. I wish I had had a chance to know her.

Related articles

- The Lower East Side (brotmanblog.wordpress.com)