Having reached (for now) a dead end on my research of the Brotman family, I have decided to turn to, or rather return to, my research of my grandfather’s family, my Goldschlager relatives. I had previously done a fair amount of research on the Goldschlager line, but had put it aside when I found my Brotman cousins. For some of you, the Goldschlager story will be perhaps of less interest, although it is itself a wonderful story of American Jewish immigration. For others, in particular my first cousins and siblings and my mother, the Goldschlager story will be of great interest. And for those who are interested in genealogy generally and/or the history of Jews in Europe and America, this story should also be a great interest.

So although this blog is called the Brotmanblog (and will continue to be so titled), I have created a new page for my Goldschlager ancestors and relatives. If you are interested, please check it out. I also will be writing some posts to describe the research I’ve done to uncover the story of my grandfather, his siblings and his parents and grandparents.

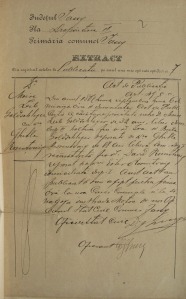

In this first Goldschlager post, I want to tell the story of my grandfather Isadore. Isadore was born in Iasi (or Jassy), Romania. He was the oldest child of Moritz (Moses, Moshe, or Morris)and Gitla (Gittel or Gussie) Goldschlager. He was born in August, 1888; his younger brother David was born the following year, and their younger sister Betty was born in 1896. Isadore was named for his grandfather, Ira Goldschlager. I was very fortunate to find a researcher in Iasi who located and translated several documents relating to these relatives, including birth records and marriage records for Moritz and Gitla, my great-grandparents.

He even took a photograph of the house were my grandfather and his parents and siblings lived in Iasi.

When my grandfather was 16 years old, he left Iasi and walked through Romania to escape the tzar’s army and persecution. Romania was one of the most anti-Semitic and oppressive countries in Europe at the time, and many Jewish residents decided to escape in the early years of the 20th century. In a subsequent post, I will write more about the conditions in Romania and the history of the Fusgeyers—the “foot goers” who left Romania on foot. My mother said that she does not remember her father talking about Romania very much, except to talk about the horses and the music, two things that he loved very much.

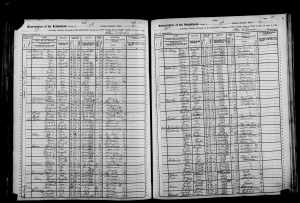

My teenaged grandfather arrived in New York City in 1904 without any relatives and under his brother’s name. In 1905 he had a job as a storekeeper in a grocery store and lived in what is now East Harlem at 113th Street, apparently alone or perhaps in a boarding house. His father Moritz arrived in 1909, and his mother Gittel, brother David, and sister Betty in 1910. Sadly, it appears that Gittel, David and Betty arrived shortly after Moritz had died.

By 1915, Isadore and his mother and siblings were living together in East Harlem. David was working at a hat maker, Betty as a dressmaker. Isadore’s occupation unfortunately is not legible on the 1915 census form. Edit: On closer examination, I believe it says “Driver Milk,” which is consistent with what he was doing for the rest of his working life.

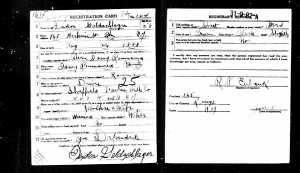

By 1917, when Isadore registered for the draft, he was working as a driver for a dairy company and married to my grandmother Gussie and living in Brooklyn.

He continued working for dairy companies and eventually became a foreman. He and my grandmother had three children. As a milkman, my grandfather worked at night to deliver the milk by morning. When he delivered milk to people in the poor communities, they all loved him so much that they would bring him food.

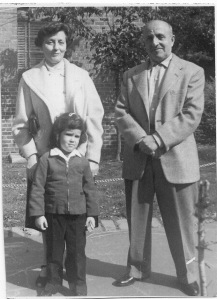

My grandparents moved to Parkchester in the 1940s with my mother, who was only twelve at the time. When I was born ten years later, my parents also lived in Parkchester, just a few buildings away from my grandparents, so I spent my first four and half years living right near my grandparents.

Although my grandfather died before I was five years old and thus my memories of him are vague, I do have a memory of him as a loving grandfather. Perhaps it is the stories I’ve heard all my life about him rather than my own memories—it’s hard to know. I know that my mother and her siblings loved him a great deal, that he was a big tease with a great sense of humor, and that although he left Romania at fifteen and never received a high school education, he spoke several languages and was a very smart and witty man. He must have been an incredibly strong person to have left his family at such a young age; most likely he helped the rest of his family come to the United States once he got here.

I wish I had known him longer, and I wish I knew more about his life both in Romania and in New York. Perhaps as I pursue this line of research I will learn more. I have just located one of David’s grandsons, Richard, and David’s son Murray is 92 and living in Arizona. I am hoping that Murray may know more about David’s life in Romania and the relationship between the two brothers, David and Isadore.