Of the thirteen children born to my great-great-grandparents Jacob and Sarah Cohen, only one was still alive in 1928. He was also the only one to live through not only the 1930s, but into the 1940s as well. He was one of only three to live into his seventies and the only one to live past 75 years old. He was also the last born, the baby of the family, Abraham. Like all his siblings, he had a life that had plenty of heartbreak.

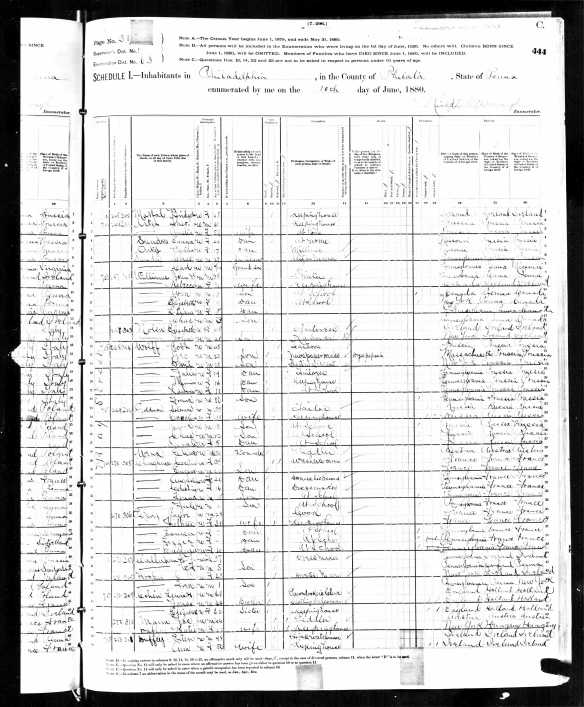

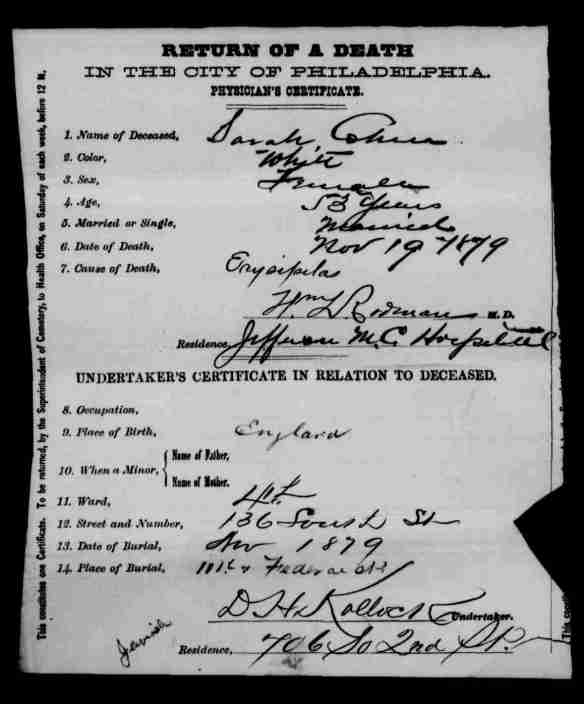

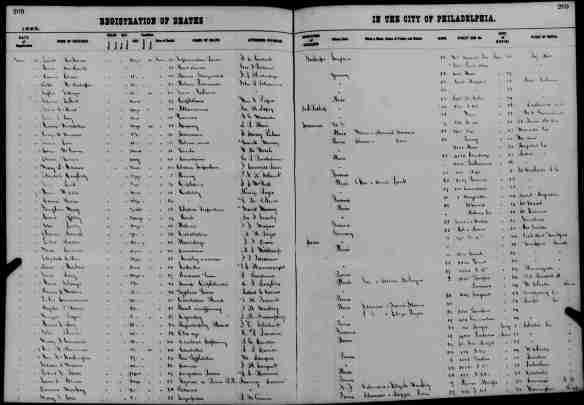

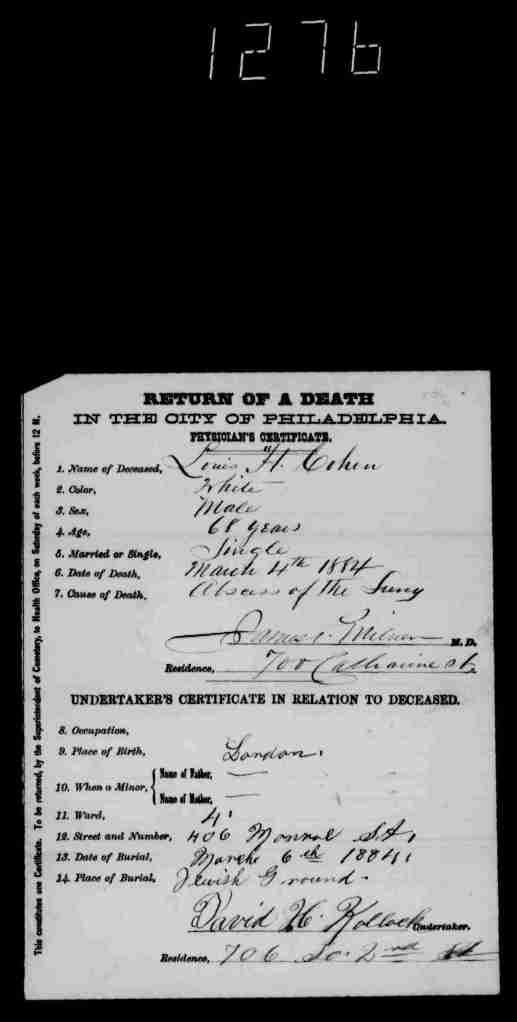

Abraham was born on March 29, 1866. His oldest sibling, Fanny, was twenty years old when he was born and was married that same year. Joseph, his oldest brother, was married two years later. But in 1870 Abraham had ten older siblings still living in his household at 136 South Street. His first real heartbreak occurred when he was thirteen and his mother Sarah died in 1879. Fortunately he still had six siblings living at home as well as his father. By the time he was fourteen in 1880, he was already working in his father Jacob’s store.

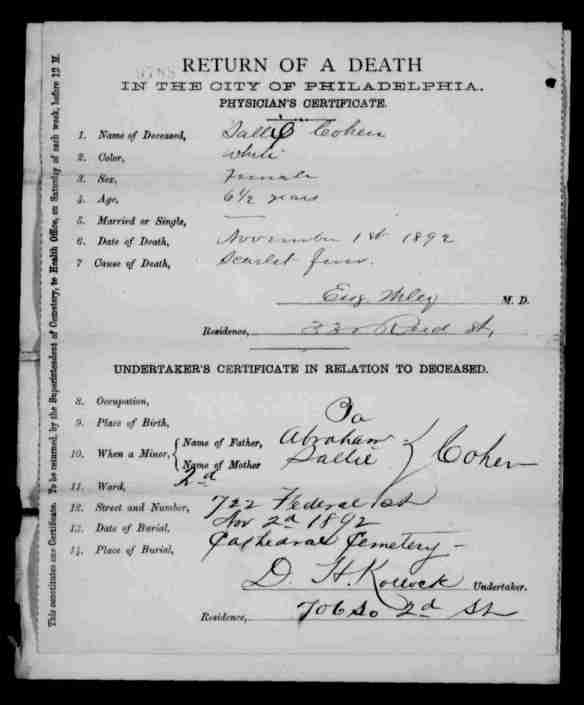

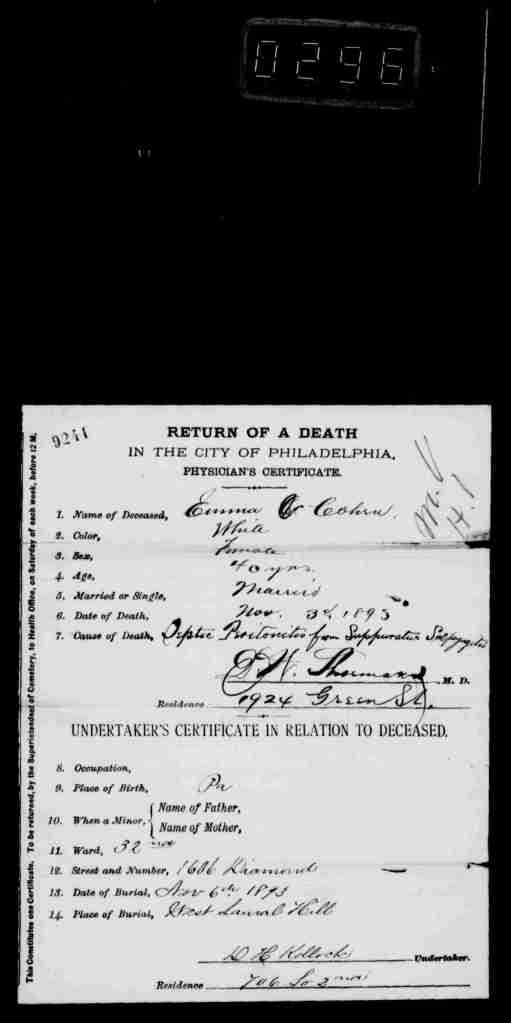

On February 9, 1886, Abraham married Sallie McGonigal, daughter of James and Sarah McGonigal, in Camden, New Jersey. Their first child, Sallie, was born in 1886. I do not have a birth record for her, but sadly, I do have her death certificate. Sallie died on November 1, 1892, when she was six and a half years old from scarlet fever. She was buried in at Old Cathedral Catholic Cemetery in Philadelphia.

Assuming that the child Sallie was born then in April or May, 1886, either she was born very premature or Sallie was already pregnant when they married. Abraham and Sallie would both have been only twenty when they married, although their marriage record listed their birth years as 1864, not 1866. I am speculating here, but since they were married out of state and under age and since it seems likely that Sallie was pregnant and since Sallie was apparently Catholic and Abraham was Jewish, I am going to venture a guess that their parents did not approve of the relationship.

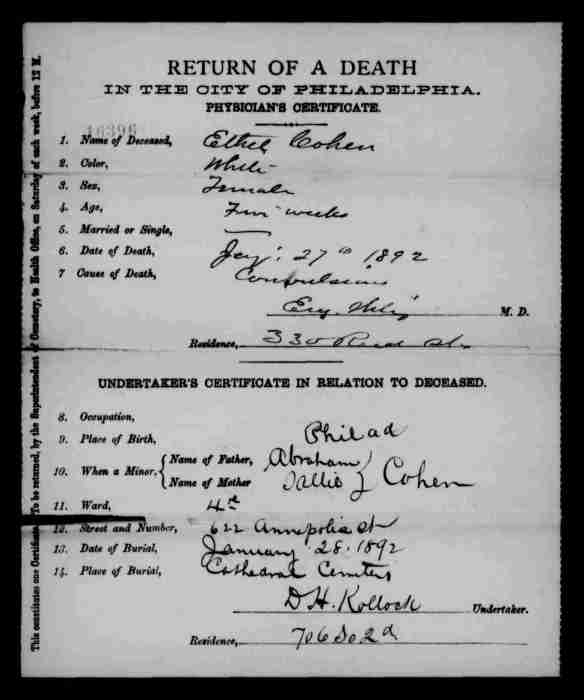

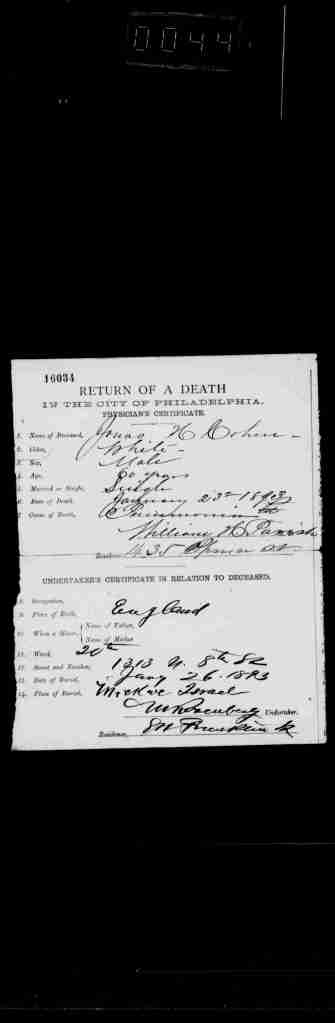

But Abraham and Sallie’s marriage survived. They had a second child, Leslie Joseph Cohen, who was born on May 20, 1889.[1] In December, 1891, they had a third child, Ethel, who only lived four weeks. She died from convulsions on January 27, 1892.

Then ten months later, they lost Sallie to scarlet fever. Sometime after those deaths, the family moved from where they had been living at 622 Annapolis Street to 707 Wharton Street, where they remained for many years.

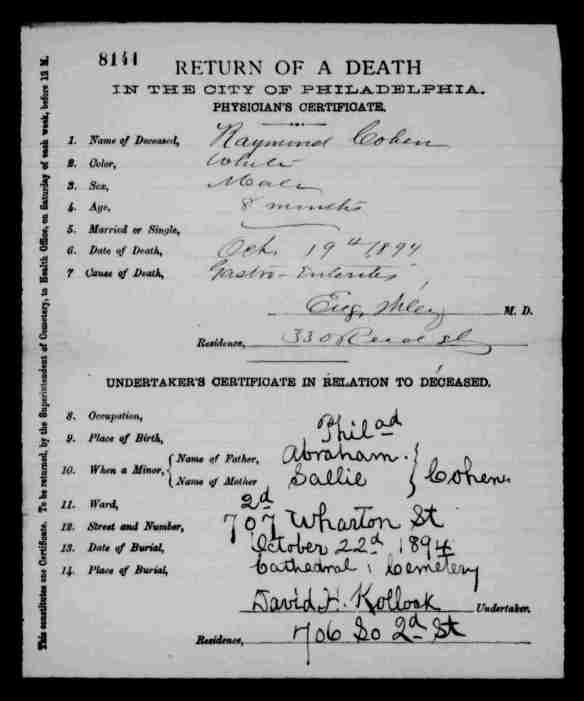

The young couple weathered those terrible tragedies and had a fourth child, Raymond, on February 15, 1894. He died eight months later from gastroenteritis and was also buried in Old Cathedral Catholic Cemetery with his sisters Sallie and Ethel.

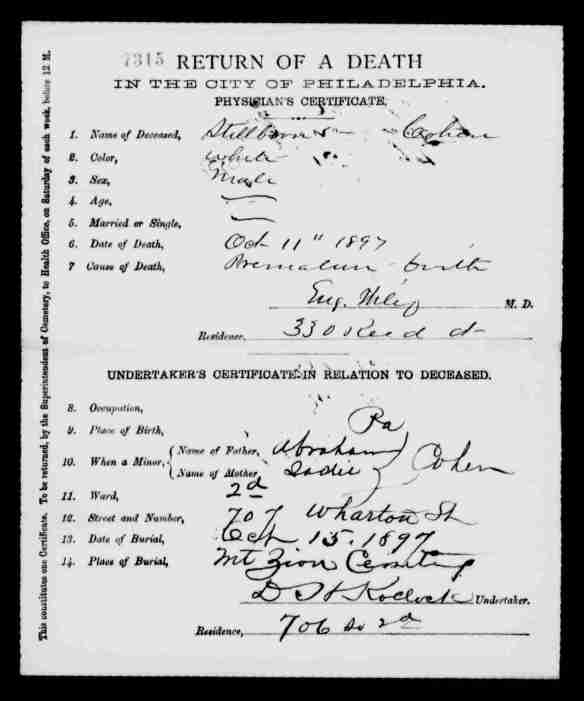

In the space of just over two years Abraham and Sallie had lost three young children. Three years later, Abraham and Sallie lost another male baby to premature birth on October 11, 1897; he was stillborn. Interestingly, that baby was buried at Mt Zion cemetery. Would a Catholic cemetery not accept a stillborn baby?

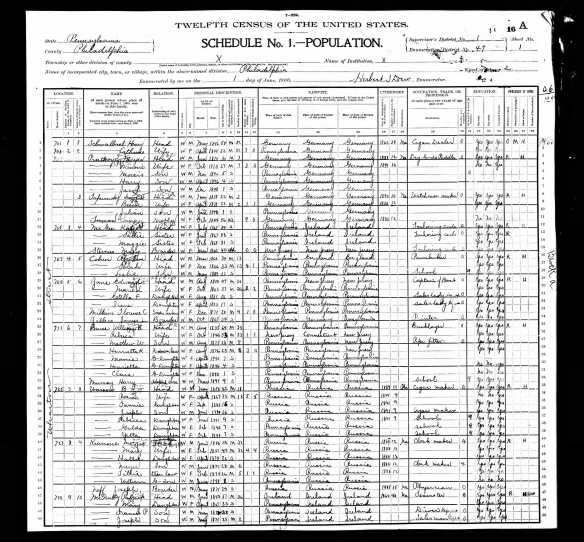

In 1900, Abraham, Sallie and their one surviving child, Leslie, were still living at 707 Wharton Street, and Abraham was working as …. a pawnbroker, of course.

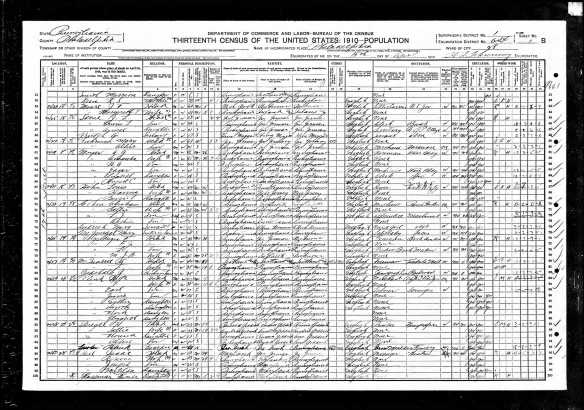

Unless I missed the birth and death of other children, it seems that after not having any children for over ten years, Abraham and Sallie had one more baby. Arthur was born on December 9, 1907, according to the Pennsylvania birth index. Assuming that Sallie was born in 1866, she was over 40 years old when he was born. In the 1910 census, Abraham, Sallie, Leslie, and Arthur were all living at 2433 North 17th Street; in addition, Sallie’s sister, Mary McGonigal, was living with them as well as a servant whose duties were described as “nurse girl.” I assume she was taking care of Arthur. Abraham was still working as a pawnbroker. Leslie was nineteen and an apprentice machinist. Arthur was two years old.

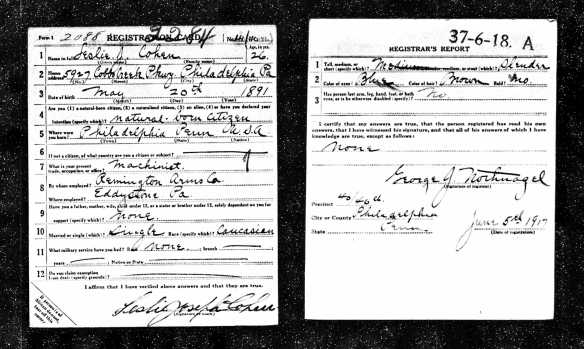

In 1917 Leslie registered for the draft. He was working as a machinist at Remington Arms in Eddystone, Pennsylvania, where his Aunt Hannah’s husband, Martin Wolf, was also employed during that period.

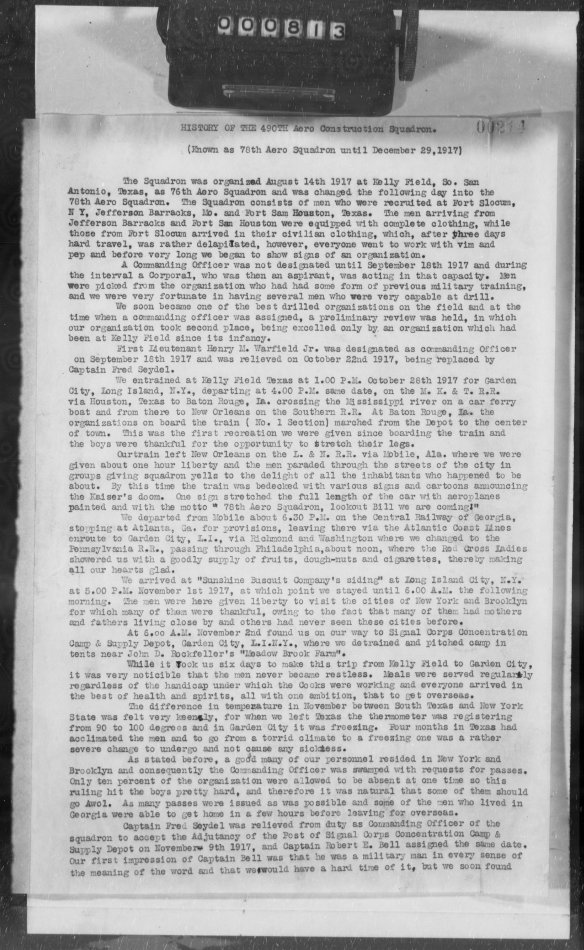

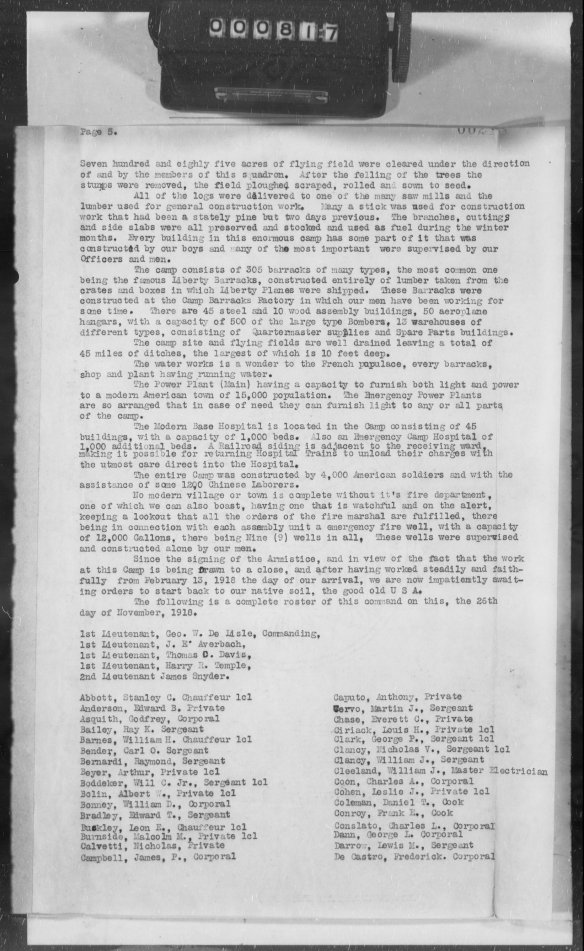

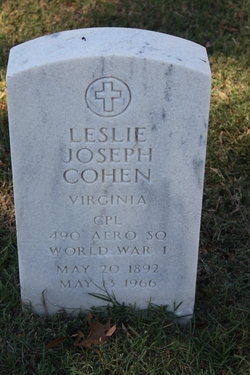

Leslie served in the military from 1917 to 1919, according to one record.[2] He served in Aero Squadron 490, as seen on his headstone below. I was able to track down a detailed five page document from Gorrell’s History of the American Expeditionary Forces Air Service, 1917-1919, describing the service of Leslie’s squadron during World War I by using the Fold3.com website.

I cannot capture all the details of his squadron’s service, but in brief, the squadron trained in San Antonio, Texas; they then traveled by train and boat from there to Long Island City in New York to await their orders to ship overseas. They received those orders and shipped out of New York to England on November 22, 1917.

The report details the rather uncomfortable conditions the men encountered while traveling from New York to Halifax to Liverpool, England over a sixteen day period, although they did not face any danger from enemy forces while traveling. They arrived in Liverpool on December 8, 1917, and then left for France on December 13, 1917, where they were first stationed at Saint Maixent and then at Romorantin. In both locations, the squadron was engaged in building barracks and other buildings for the soldiers. They also built over sixteen miles of railroad. The report described in detail the facilities at their second location and the work that was done. It ends after the Armistice was signed, saying that the squadron was awaiting their orders to return to the United States. Leslie J. Cohen is listed three times in the course of the report on the roster of men who served with the 490 Squadron, including on the final page shown below.

(M990;Publication Title: Gorrell’s History of the American Expeditionary Forces Air Service, 1917-1919

Publisher: NARA

National Archives Catalog ID: 631392

National Archives Catalog Title: Gorrell’s History of the American Expeditionary Forces Air Service, compiled 07/05/1917 – 08/31/1919, documenting the period 05/26/1917 – 03/31/1919

Record Group: 120

Short Description: NARA M990. Historical narratives, reports, photographs, and other records that document administrative, technical, and tactical activities of the Air Service in the American Expeditionary Forces during World War I.

Roll: 0021

Series: E

Series Description: Squadron Histories)

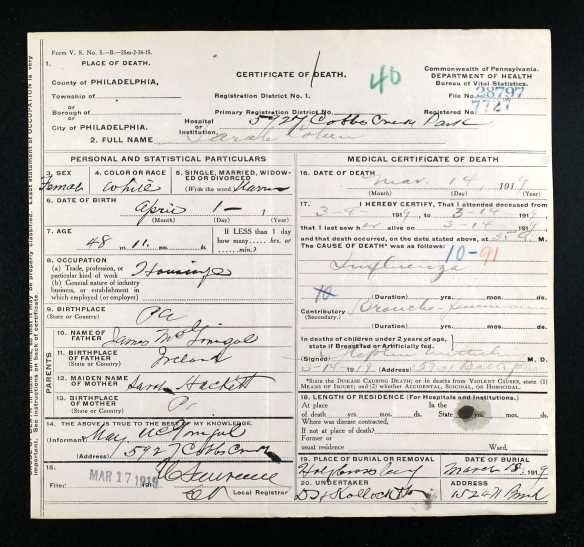

Back home in Philadelphia, Abraham’s wife Sallie died on March 14, 1919, and surprisingly was buried not with her children at Old Cathedral Catholic Cemetery, but at Holy Cross Cemetery in Yeadon, Pennsylvania. The family was residing at 5926 Cobbs Creek Parkway when she died, which was only a mile from Holy Cross Cemetery; nevertheless, Cathedral Cemetery, where so many of her children were buried, was only three miles away. I wonder why she was not buried with her children. Sallie died from influenza, pneumonia and bronchitis. This was the time of the deady Spanish flu epidemic that killed millions of people worldwide. Sally was about fifty years old when she died, and her son Arthur was only eleven years old.

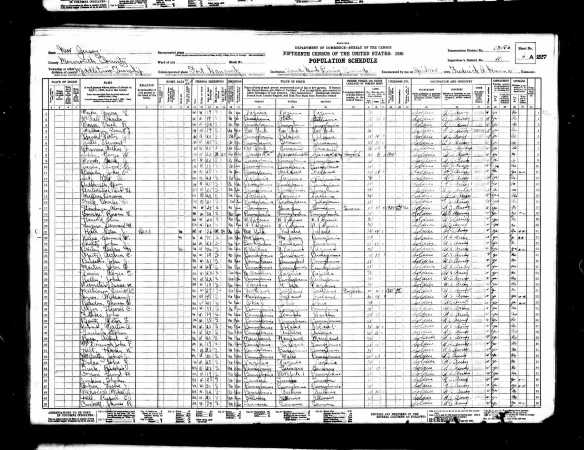

As of January 10, 1920, when the next census was taken, Abraham, now a widower, was still living at 5926 Cobbs Creek Parkway with his sons Leslie and Arthur, his sister-in-law Mary McGonigal, and a servant. Abraham was still a pawnbroker; Leslie was a machinist in the shipyard, having returned from military service. Arthur was in school.

Sometime later in 1920, Abraham married Elizabeth Beisswagner Grady, whose husband Robert Grady had died in 1918 and, interestingly, is also buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Yeadon, Pennsylvania. Had Abraham met her at the cemetery? At the church? Elizabeth had several children from her first marriage, though all would have been adults by 1920. Abraham was 54 when they married, Elizabeth was 46.

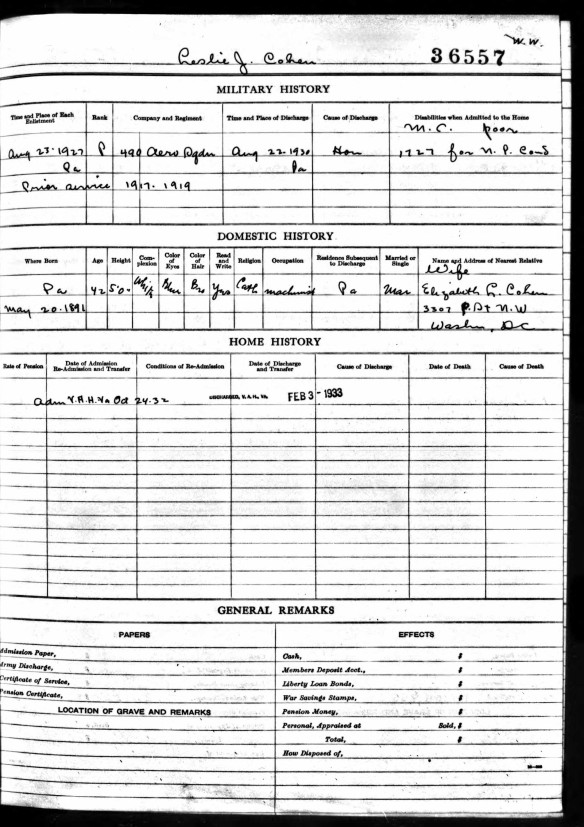

In 1927, Leslie reenlisted in the army, and on the 1930 census he is listed as a soldier in the US Army, stationed at Fort Hancock in Middletown Township, New Jersey. He served from August 23, 1927 until August 22, 1930, when he was honorably discharged.

In the 1931 directory for the city of Richmond, Virginia, Leslie is listed with his wife Emma L. and was employed as a machinist. Thus, sometime between the date of the 1930 census and the date of the Richmond directory, he had gotten married and moved to Richmond. He was later admitted to the Veterans Administration Hospital in Virginia on October 24, 1932, and released on February 3, 1933. I cannot tell from the record why he was admitted or why he stayed for over three months in the hospital. The hospital record also indicated that he was married to an Elizabeth L. Cohen (presumably a mistake; other records corroborate that her name was Emma), living in Washington, DC.

Meanwhile, back in Philadelphia, Abraham, Elizabeth, and Arthur were living at 5530 Walnut Street according to the 1930 census. Abraham was still working as a pawnbroker, and Arthur was working as a porter at a gas station. Abraham, who was now 64 years old, had outlived all his siblings at this point as well as his first wife and several of his children. I find it interesting that neither of his two sons became pawnbrokers, given the Cohen family’s overall involvement in that industry.

Abraham’s second wife Elizabeth died on August 4, 1939, from heart disease. They had been living on Spruce Street, where Abraham is listed as living alone on the 1940 census. He was still working as a pawnbroker at age 74. Elizabeth was buried with her first husband Robert Grady at Holy Cross Cemetery in Yeadon.

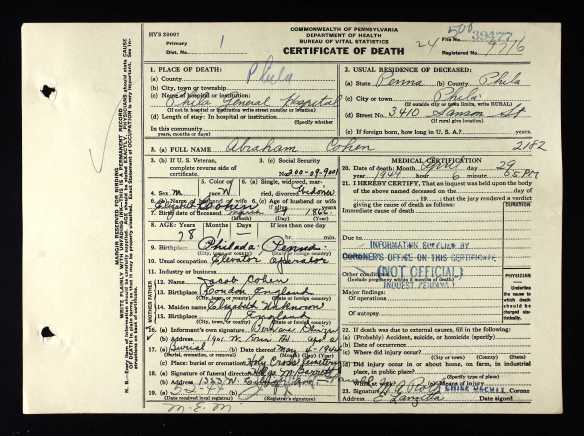

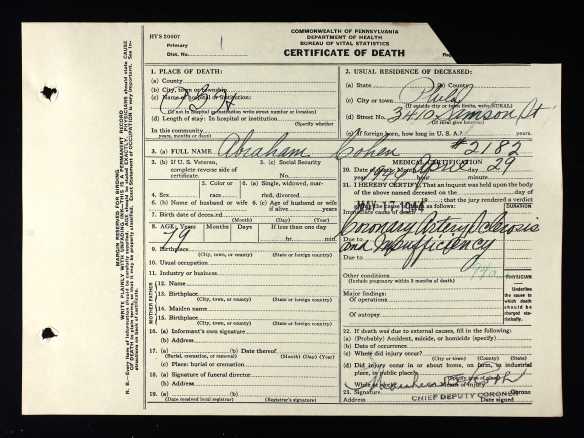

Abraham died on April 29, 1944, when he was 78 years old. He also was buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Yeadon with his first wife Sallie. His death certificate was subject to a coroner’s inquest for some reason, but the inquest found that he died from arteriosclerosis.

The only strange thing about his death certificate is the description of his occupation: elevator operator. After a lifelong career as a pawnbroker, why would Abraham have become an elevator operator? The informant on his death certificate was Bernard Sluizer, Abraham’s brother-in-law, the widower of Abraham’s sister Elizabeth. Bernard would die just four months later. Why would Bernard have been the informant? Well, all of Abraham’s siblings had died many years earlier, as had all their spouses except for Bernard and Jonas’ wife Sarah. Leslie was living in Richmond, Virginia. I don’t know where Arthur was at that time.

Leslie and his wife Emma continued to live in Richmond, Virginia during the 1930s and 1940s. According to the 1940 census, Emma was almost twenty years older than Leslie. She is reported to have been 67 in 1940 while he was 48. Leslie also appears never to have returned to his skilled position as a machinist. On various Richmond directories throughout this period, his occupation is described as a helper, one time specifying at a Blue Plate Foods. It is obviously hard to make too many inferences, but given his hospitalization and his low skilled employment afterward, it would seem that Leslie might have been disabled in some way after his second service in the army. Leslie died on May 13, 1966, and is buried at Fort Harrison National Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia.

As for Arthur, I just am not sure. There were two Arthur Cohens living in the Philadelphia area who were born in Pennsylvania in or about 1907, according to the 1940 census. Both were married. One was working as a manager in a bottling company, the other as a mechanic in a garage. Since Arthur was working in a gas station in 1930, I am inclined to think that it is more likely that he was the second Arthur, who was married to a woman named Claire. They were living in Upper Darby, a Philadelphia suburb in 1940, but had been living in Philadelphia in 1935, according to the 1940 census. If this is the right Arthur Cohen, it seems that he and Claire moved out to California at some point, living in Burbank in the 1970s and 1980s, and then to Las Vegas thereafter where Claire died on June 11, 1998. I am still not positive I have the correct Arthur, so will continue to look for more records or documents to corroborate my hunch.

Thus, there are some loose ends here. I don’t know the full story of Leslie and his wife Emma, but if the ages on the 1940 census are correct, it seems very unlikely that there were any children. Arthur’s story is even more unfinished. Without a marriage record or a death certificate, it’s impossible to be sure that I have found the right person. I also do not have any idea whether Arthur had children.

Looking back over Abraham’s life is painful. He lost so much—his mother when he was just 13, his father nine years later, and all his siblings between 1911 and 1927. Three of his children died when they were very young, and he outlived two wives. One son had moved away to Richmond, Virginia, possibly disabled in some way. The other one seems to have disappeared or moved out west at some point. I have this sad image of Abraham as a man in his seventies, living alone, working as an elevator operator, and having only his brother-in-law Bernard Sluizer around as his family (and perhaps many nieces and nephews as well).

I hope I am wrong.

************

That brings to an end, for now, the long story of the thirteen children of Jacob and Sarah Cohen, my great-great-grandparents. I will reflect on what I’ve learned about them and try and synthesize it all in my next post.

[1] Leslie’s birth year changed from record to record. Sometimes it was 1891, sometimes 1892, sometimes 1893. The record closest to his birth year was the 1900 census, which indicated that he was then 11 years old, giving him a birth year of 1889. However, on the 1910 census, his age was 19, meaning he was born in 1891. His two draft registrations also vary. His headstone says 1892. They all say his birthday was May 20, regardless of the year.

[2] Ancestry.com. U.S. National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, 1866-1938 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007.

Original data: Historical Register of National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, 1866-1938; (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1749, 282 rolls); Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15; National Archives, Washington, D.C.