I am continuing to read Joseph Margoshes’ A World Apart in order to learn about life in Galicia in the late 19th century. Last night I learned something about arranged marriages in Galicia. When Margoshes was only fourteen years old, his mother began to look for a prospective bride for her son. Since Margoshes’ father had died, Margoshes was a candidate for an early marriage in order to relieve his mother of the burden of supporting him and caring for him. Margoshes also said that early marriage was a way “to avoid moral lassitude, or strange and sinful thoughts, God forbid.” (p. 58)

Margoshes then described how shadken, or matchmakers, would come to his school to observe and evaluate the young boys in his class as potential grooms. Margoshes was considered a very attractive candidate: he was tall, good-looking, well-educated and from a well-regarded family. His mother was presented with many different potential matches. Margoshes reported that parents never spoke to their children about these potential matches; it was all out of their hands and determined by the parents. His mother rejected a number of potential brides because they were “unrefined upstarts of a very low social status…[who] would bring shame to his father’s grave…” (p. 60)

Eventually his mother agreed to an appropriate match, the daughter of a very successful man, Mordecai Stiglitz, who lived in Zgursk, a village near Radomisha, a town not too far from Tarnow where Margoshes and mother and brother were then living. As described by Margoshes, Stiglitz had a big estate that he had acquired through successful leasing arrangements with the descendant of a Polish count who had owned several thousand acres in the area. Stiglitz’s estate was itself thousands of acres, and he had many head of cattle, 40 horses, 40 oxen, 70-80 milk cows, and about 30 peasants who lived and worked on the estate. They grew grain and grass on the estate and needed workers to tend to the livestock and to cut and care for the grain and grass, which they baled and sold in the market.

The Stiglitz family met Margoshes’ mother’s standards, and Margoshes was subjected to an evaluation of his knowledge of Gemara, Talmud and Jewish law in general. He passed the test and was approved as a groom for Stiglitz’s daughter (whose name is never mentioned by Margoshes in his telling of this story). Margoshes was only sixteen years old at that point.

After a lavish wedding with three feasts, including one for the poor Jews and beggars who lived in the area, Margoshes moved to Zgursk to live with his new bride on her father’s estate. As Margoshes wrote, “Initially I did not really know my bride; we had only seen each other and talked very little during the engagement ceremony, and then not even exchanged a letter. However, as soon as we got to know each other better after the wedding, we became as intimiate and loving as if we had known one another for many years. This heart felt love has continued to this day, thank God, for over fifty years and will remain until the end of our lives.” (p. 65) Two teenagers whose marriage was arranged by their parents and who did not know each other at all somehow managed to fall in love and create a long and happy life together.

I have heard and read about arranged marriages before, not only in Jewish families, but in many other cultures as well. We recently watched an excellent movie, “Fill the Void,” about contemporary Israel and arranged marriages among the Hasidim today. I know that often these marriages did not end up so happily, but it does seem that more often they worked—that two people who did not know each other somehow fell in love or at least developed a strong enough bond to create a lasting relationship. It is so foreign to my own experience—I cannot imagine letting my parents select a life partner for me or marrying someone I’d only met once. Yet I also cannot pass judgment on the practice since it does seem that often parents do know what is best for their children.

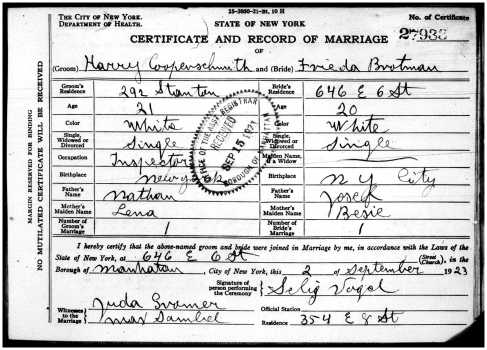

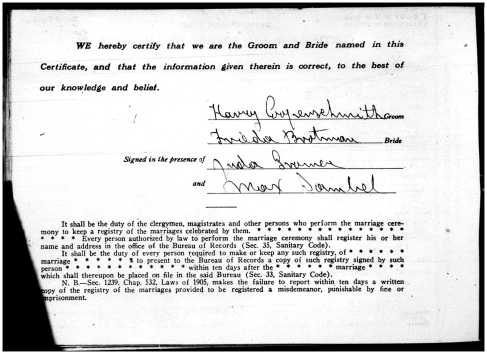

I have to assume that Joseph’s marriage to Bessie was itself an arranged marriage. Joseph was a widow (or so we assume; perhaps his first wife had left him) with at least two young sons, Abraham, who would have been about nine, and Max, who would have been about three. Bessie was his cousin and at least ten years younger than Abraham and about 24 when she married him. Based on the customs of the day and the circumstances, most likely a matchmaker put together these two cousins so that Bessie would have a husband and so Joseph would have a wife and a mother for his children. Did they grow to love each other? Or was it purely a convenient arrangement? The inscription on Joseph’s footstone certainly suggests that he was a good husband and father, so I’d like to think that, like Margoshes and his bride, Joseph and Bessie developed a loving marriage. But then I am a hopeless romantic!

Related articles

- Arranged Marriage (beingbrownskinned.wordpress.com)

- Love or arranged marriage? (rosalieboucher.wordpress.com)