I am now reading another memoir, Streets: A Memoir of the Lower East Side. The author, Bella Spewack, had quite an interesting life. She moved with her mother, Fanny Cohen, from Transylvania to NYC in 1902 when she was just three years old. Fanny Cohen was just a teenager herself and had been abandoned by Bella’s father shortly after Bella was born. They arrived in NYC with no resources, no money, no relatives to help them, and yet somehow Bella grew up to be a successful journalist first and then a very successful Broadway playwright along with her husband, Sam Spewack. They are perhaps best known for the Tony award-winning play, Kiss Me Kate.

Bella wrote Streets in the 1920s while living in Berlin with her husband as foreign correspondents, but like A World Apart, it was not published until relatively recently (1995). I chose to read this book to get an idea of what life was like for our family when they were living on the Lower East Side in the 1890s and early 20th century.

Whereas A World Apart failed to convey what life was like for poor Jews living in Galicia, Spewack does not shy away from depicting the hardships endured by Jewish immigrants living on the Lower East Side in the first two decades of the 20th century. In the first chapter, Spewack describes how her mother scratched together a living in the early years after they first arrived in New York. Like many young immigrant women, Fanny started by looking for employment as a house servant right after she arrived in the US. Fanny and Bella lived behind a restaurant those first days and shared a bed with two strangers. When after some time, Fanny finally secured a position as a servant, she found the man of the house at her bedside in the middle of the night. Fanny left and returned to the restaurant and started looking again. Her second position was in Canarsie (Brooklyn), where she lasted somewhat longer until Fanny intervened to protect a girl living in that home from sexual assault.

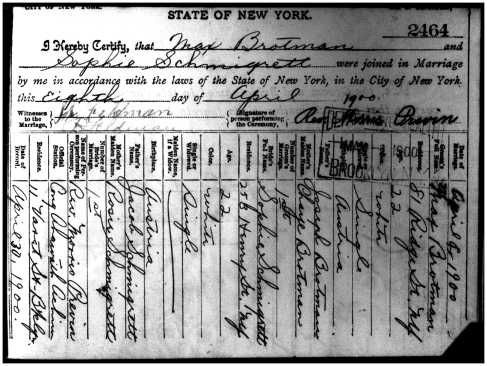

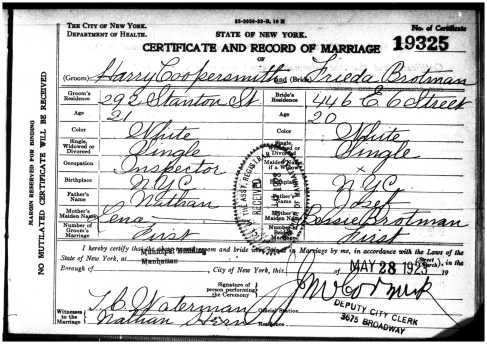

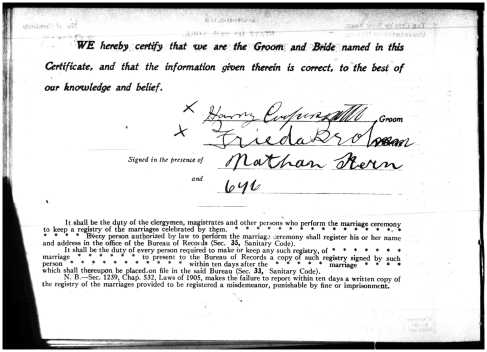

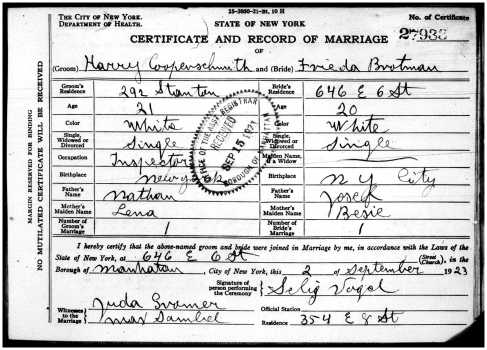

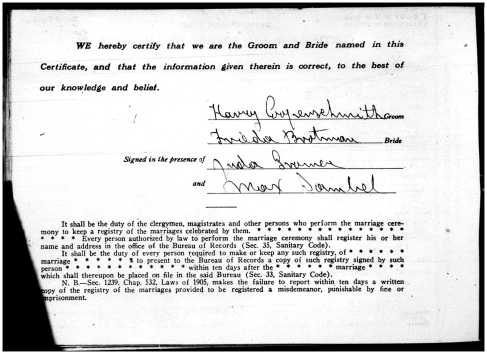

My eyes opened wide when I read that they then returned to the Lower East Side and stayed with a woman they called the Peckacha who lived on Ridge Street. (The woman had a pock-marked face, and I assume that’s what the nickname meant.) This would have been in 1902, the year after Joseph died, when Bessie and the children were living on Ridge Street. Since Frieda was then five and Gussie was seven, it is entirely possible that little Bella knew our family. Of course, since there were probably thousands of people living on Ridge Street, it’s also possible and probably likely that they never met, but it made reading this section more meaningful for me as it helped me imagine what life was like for those other two little girls, my grandmother and her little sister. Unfortunately, Bella’s experience with the Peckacha and her children was not a pleasant one. The children would pick on her, both verbally and physically, while Fanny was out working.

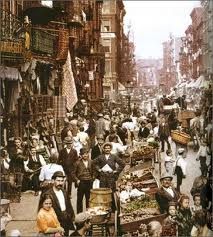

Bella described Attorney Street, the street one block west of Ridge as like Orchard Street, “a market where fruit and vegetable dealers sell to the street and store vendors. Cases, bulging with oranges or apples and watermelon, line the streets, while men with live, dirty hands darted among them with eyes that took in everything. People live on these streets as well, rotting in their cases with the overripe fruits.” (p. 8)

Fanny soon decided that she would prefer working in a factory to being a house servant. Her next job was working as an operator in a ladies’ shirtwaist factory for $7.50 a week. Bella and Fanny moved to Cannon Street where they lived with a widow named Pincus. Bella went to a day nursery while her mother was at work. The nursery was located in the basement of a building on Cannon Street, which Bella described as “gloomy but much warmer than the rooms all of us had just left.” Overall, Bella’s experience at the day nursery sounded positive, with pleasant caretakers, but the days were very long, stretching past seven at night, and the space was overcrowded with too many babies and young children.

Unfortunately, once again Bella experienced some abuse. Fanny trusted Mrs. Pincus, her landlady, to get Fanny up and to the nursery, and Mrs. Pincus ended up hitting and pinching Bella, once leaving her with such a huge bruise that Bella had to admit to her mother that Mrs. Pincus was abusing her. These experiences finally led Fanny to decide that she needed to find a place of her own where she would take in boarders to help pay the rent and provide her with some income. She found a place in a new building on Cannon Street near Rivington Street, a three room apartment (bedroom, kitchen and dining room) with its own bathroom, and took in several boarders.

In the foreword to the book, Ruth Limmer provided a description of early tenement houses: “horrific five- and six- story dwellings that…lacked toilets, running water, fire escapes, and landlord-supplied hear and cooking stoves.” (p. xix) By 1903, however, newer buildings had been built that were somewhat of an improvement. “Now each apartment had, in addition to its windowed “front room”…another room that opened onto an air shaft, and interior windows were cut into the walls in order to permit a flow of air. Little by little, the apartments were fitted with piping for illuminating gas. And instead of backyard privies, families got to share indoor toilets, two per four-apartment floor. The law also required that fire escapes be affixed to all buildings.” (p. xix) The tenements were built on lots originally intended for single family dwellings ( 25 feet by 100 feet), but they housed over twenty families plus boarders in each building.

I imagine that this is like the apartment that Fanny and Bella were renting in 1903 and likely also what the Brotmans were living in on Ridge Street. The census from 1900 did not list boarders as living in the Brotman household; perhaps Joseph’s income as a coal carrier/dealer was sufficient to support the family, though I doubt their standard of living would be acceptable to any of us today.

Bella described the many boarders, both men and women, who shared their small space, men sleeping in the kitchen, women in the living room and bedroom with Bella and Fanny. You can imagine the goose bumps I got when I read that two of the young girls living with them at the beginning were named Frieda and Gussie. Obviously, those girls were not our Frieda and Gussie, and those were common names for Jewish girls at that time, but nevertheless, once again the book made me realize that I was reading not about some foreign land or a work of fiction, but a work that reflects what life must have been like for the Brotman family living on Ridge Street in 1900.

More to come….

Related articles

- The Lower East Side Looks Like the Early 1900s Right Now (animalnewyork.com)