My great-great-uncle Jacob Katzenstein was, like his sister Brendena, a man who faced a great deal of tragedy but managed to survive and, in his case, start all over with a new family. In 1889, he lost first born child, Milton, at age two and a half, and then both his wife, Ella Bohm, and his other young son Edwin in the devastating Johnstown flood. I’ve written about Jacob and these events in prior posts.

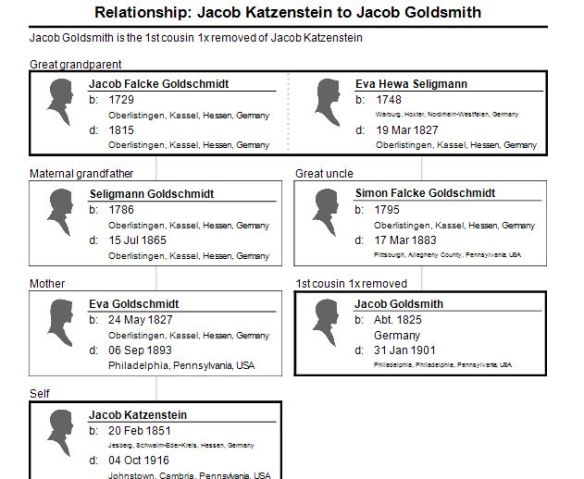

In one of those posts, I also described my search for more information about Ella Bohm and my hypothesis that she was the daughter of Marcus Bohm and Eva Goldsmith; I assumed Eva was her mother as Ella is listed on the 1880 census as the niece of Jacob Goldsmith, Eva’s brother. Eva Goldsmith was also my distant cousin—her mother was Fradchen Schoenthal, my great-grandfather Isidore’s sister; her father was Simon Goldschmidt, my great-grandmother Eva Goldschmidt’s uncle. And if I am right that Ella Bohm was Eva Goldsmith’s daughter, then Ella married her cousin when she married Jacob Katzenstein, as he was Eva Goldschmidt’s son.

But I had no definitive proof that Eva Goldsmith was Ella’s mother. I also had not been able to find out when Jacob Katzenstein married Ella or why their first-born son Milton died. On my cousin Roger’s old genealogy website, he had included a quote about Jacob from a book called The Horse Died at Windber: A History of Johnstown’s Jews of Pennsylvania by Leonard Winograd (Wyndham Hall Press, 1988). I decided to track down this book to see if it revealed any more information about Jacob Katzenstein and Ella Bohm and their lives.

I was able to borrow a copy of the book through the Interlibrary Loan system from my former employer, Western New England University, and have now read the book. Unfortunately it did not answer my two principal questions. I still don’t know for sure who was Ella Bohm’s mother, and I still don’t know what caused the death of little Milton. I did, however, learn more about Ella’s father Marcus Bohm, about Jacob Katzenstein and his second wife Bertha and their children, and about the Johnstown Jewish community at that time and its history.

According to Winograd, in the second half of the 19th century when many Jewish immigrants started arriving from Europe, many made a living as peddlers, as I’ve written about previously. Pittsburgh was a popular hub where these peddlers would obtain their wares and then travel by foot or horse and wagon or train to the various small towns in western Pennsylvania. Winograd states that by 1882 there were 250 to 300 peddlers operating this way out of Pittsburgh. (Winograd, p. 12)

Eventually these peddlers would find a particular town to settle in and would set up store as a merchant in the town. But Pittsburgh remained the center for Jewish life. These merchants and peddlers would attend synagogue there, participate in Jewish communal life there, and be buried there. Often they would move on from one town to another or return to Pittsburgh itself. (Winograd, p. 12-13)

Johnstown was a bit too far to be part of this greater Pittsburgh community (65 miles away), and although peddlers and merchants did come through there and even settle temporarily there, it was a more isolated location than the towns that became satellites of Pittsburgh. Thus, its social, economic, and religious life was independent of the Pittsburgh influence.

Winograd reported that Johnstown had a population growth spurt between 1850 and 1860, jumping from 1,260 to 4,185. In 1856, there were nine churches in Johnstown, but no synagogue (although there was apparently an attempt to start one in 1854). The Jewish families in the town had services in their homes; there was not a large enough population to support the establishment of a synagogue at that time. (Winograd, p. 26) In 1864, the Jewish merchants in town formed a merchants’ association regulating store hours. Most of these merchants came from the Hesse region of Germany, as did Jacob Katzenstein. (Winograd, p. 48)

Two of those early merchants in the 1860s were Sol and Emanuel Leopold. (Winograd, p.56) It was their sister Minnie Leopold and her husband Solomon Reineman with whom Marcus Bohm was living in 1910; Solomon Reineman came to Johnstown in 1875. (Winograd, pp. 77-78) Sol and Emanuel Leopold’s other sister Eliza Leopold Miller was Bertha Miller’s mother—that is, Jacob Katzenstein’s mother-in-law when he married Bertha Miller. As Winograd points out in Appendix C to his book (pp. 281-283), many of the Jewish merchants in town were related either directly or through marriage.

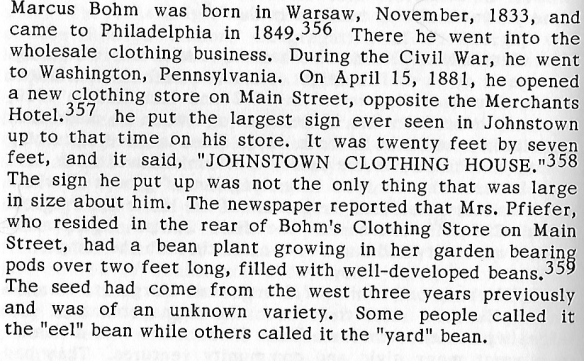

According to Winograd, both Marcus Bohm and Jacob Katzenstein came to Johnstown in the 1880s. Here’s what he wrote about Marcus Bohm:

(Winograd, p. 78)

Winograd wrote that Jacob Katzenstein first came to Johnstown in 1882 as a clerk for another merchant. He married Ella Bohm on March 26, 1883, (Johnstown Daily Tribune, May 16, 1883, p. 4, col. 7). Winograd even mentioned their wedding. In discussing what he described as “the first public Jewish wedding” in Johnstown, which took place in 1886, Winograd says, “There had been an earlier Jewish wedding, that of Jacob Katzenstein to Ella Bohm on March 26, 1883, a private ceremony conducted by J.S. Strayer, Esquire.” (Winograd, pp. 93-94) The implication appears to be that Jacob and Ella might have been the first Jewish couple married in Johnstown. Based on the date, I was able to locate a marriage notice from the May 16, 1883, edition of the Johnstown Daily Tribune (p. 4, col. 7).

According to Winograd, Jacob and Ella lived in rooms over the store of another Johnstown merchant, Sol Hess. Sol Hess was the brother-in-law of Emanuel Leopold, who had married Sol’s sister Hannah. In March 1884, Marcus Bohm moved in with Jacob and Ella and soon thereafter, Marcus lost his own store when an Eastern dealer executed a judgment of $2,625 dollars against him. (Winograd, pp.78-79)

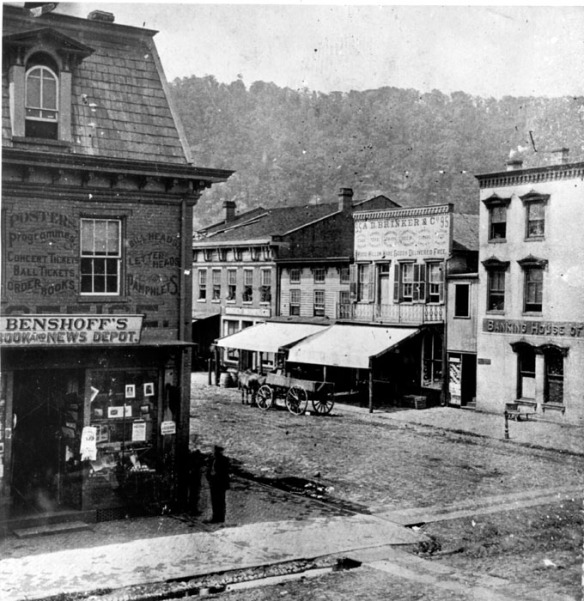

According to Winograd, Jacob moved back to Philadelphia for a few years. This must have been when Jacob and Ella’s first son Milton was born in 1886, but by June 1887 when Edwin was born, they must have returned to Johnstown. Here is a photograph of Johnstown in 1880s, showing what it must have looked like when Jacob Katzenstein first settled there:

Johnstown in the 1880s

located at http://www.jaha.org/edu/flood/why/img/before_gallery/pages/Benshoffcorner.html

As noted, 1889 was a tragic year for Jacob. First, there was the tragedy of Milton’s death on April 18, 1889 (Johnstown Daily Tribune (April 18, 1889, p. 4, col. 2), and then the deaths of Ella and Edwin on May 31, 1889, during the flood. According to Winograd, Ella and little Edwin were in their house on Clinton Street when the flood waters rushed into the city, causing the house to collapse. After the flood, Jacob lived in one of the temporary structures erected in Johnstown’s Central Park. (Winograd, p. 79)

The Johnstown Flood https://www.nps.gov/Nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/5johnstown/5johnstown.htm

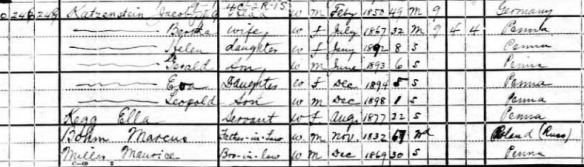

In March 1891, almost two years after losing his two sons and his first wife, Jacob married Bertha Miller, the daughter of Eliza Leopold and Samuel Miller of Pottstown, Pennsylvania. Jacob and Bertha had six children: Helen (1892), Gerald (1893, presumably named for Jacob’s father Gerson Katzenstein), Eva (1894, presumably named for Jacob’s mother Eva Goldschmidt), Leopold (1898), Maurice (1900), and Perry (1904)(named for Jacob’s brother Perry). Jacob was still a clothing merchant.

Jacob Katzenstein and family 1900 census

Year: 1900; Census Place: Johnstown Ward 1, Cambria, Pennsylvania; Roll: 1388; Page: 12A; Enumeration District: 0124; FHL microfilm: 1241388

It was during the 1880 and 1890s that formal, organized Jewish life really developed in Johnstown. Before that time, the primarily German Jewish residents of the town, who came from a Reform background and, as Winograd observed, identified more as German than Jewish in many ways, had services in their private homes and holiday celebrations with their families, but there were no official synagogues or rabbis in the town. (Winograd, pp. 77, 87-88, 103-107)

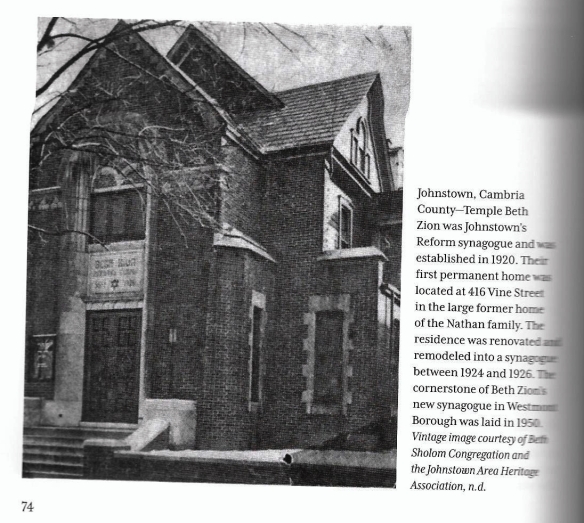

Then, with an influx of Russian Jewish immigrants in the 1880s who came from a more traditional, Orthodox background, there was a demand for more of the organized elements of Jewish communal life, including a synagogue, Hebrew school, and kosher butcher. (Winograd, pp. 76-77) In the 1890s, two synagogues were organized: Rodeph Shalom for the more Orthodox Jews in town and Beth Zion for the Reform Jews.

Beth Zion grew out of a Jewish social club, the Progress Club, of which Jacob Katzenstein was an organizer and founding member in 1885. (Winograd, pp. 80, 148). The group used their building (known as the Cohen building) for services, but it was not until 1894 that they had their first Reform High Holiday Service; there was still no full time rabbi, and lay people often led services. (Winograd, pp. 148-151)

Beth Zion synagogue in Johnstown

Courtesy of Julian H. Preisler. The Synagogues of Central and Western Pennsylvania: A Visual Journey (Fonthill Media 2014), p. 74

Courtesy of Beth Shalom Synagogue and the Johnstown Area Heritage Association

Jacob was an officer in Beth Zion Temple. (Winograd, pp. 79-80) In 1905 he donated five dollars to a fund to provide assistance to Jews in Russia who were being persecuted. (Winograd, pp. 114-116) In 1907, his son Gerald celebrated becoming a bar mitzvah the evening before Rosh Hashana; in 1912 when Gerald’s brother Leo became a bar mitzvah, it also was celebrated during the high holidays. Winograd described the Beth Zion congregation at that time as small, but tightly knit. (Winograd, pp. 150-151) Obviously, Jacob Katzenstein and his family were active members in this community.

By 1910, Jacob and Bertha’s children ranged in age from five to eighteen and were all still living at home. Jacob listed his occupation as a retail merchant, the owner of a clothing store:

Jacob Katzenstein and family 1910 US census

Year: 1910; Census Place: Johnstown Ward 1, Cambria, Pennsylvania; Roll: T624_1323; Page: 11A; Enumeration District: 0118; FHL microfilm: 1375336

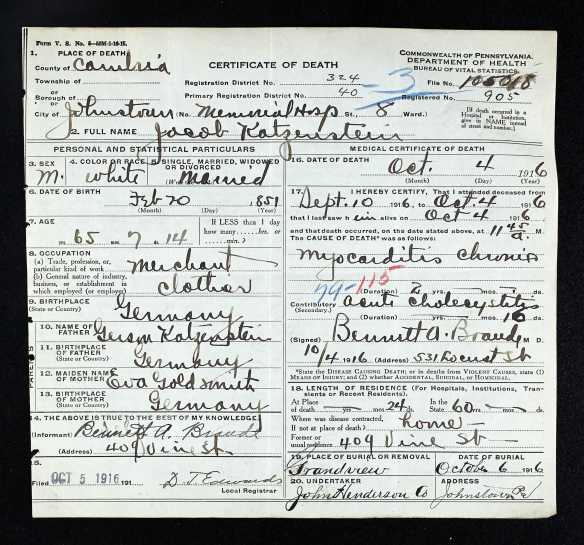

Six years later on October 4, 1916, Jacob Schlesinger died at age 65 from chronic myocarditis and acute cholecystitis, an inflammation of the gall bladder. Rabbi Max Moll, a rabbi from Rochester, New York who was in Johnstown for the high holidays, presided at Jacob’s funeral. (Winograd, p. 80) Jacob left behind his wife Bertha and his six children ranging in age from 12 (Perry) up to Helen, who was 24. In his will, executed on September 6, 1916, a month before he died, he appointed his wife Bertha to be his executrix and left his entire estate to her. Jacob was buried at the Grandview Cemetery in Johnstown.

Jacob Katzenstein death certificate

Pennsylvania Historic and Museum Commission; Pennsylvania, USA; Certificate Number Range: 102541-105790

My next post will address what happened to his six children.

(Does anyone know why that World War I sign would be posted near Jacob’s headstone? He died before the US entered the war so was not a veteran.)

I love the way you weave the history of individual family members with the wider social context Amy. That makes your posts so enjoyable to someone (like me) for whom American history is a fairly blank canvas.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Su. It helps me imagine their lives when I think about the world around them. And believe me, NZ history is a completely blank canvas for me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know what you mean; life events make so much more sense when seen in the social context. I studied NZ history at school, but am learning so much more researching the Big T’s family. And of course, lots of Scottish history researching my own.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hate to admit that aside from Braveheart and Macbeth (neither of which is factual), I know nothing about Scottish history either. We Americans are so parochial…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hm; I’d probably trust Shakespeare over Mel Gibson, but neither all that much.

I do know that a lot of the US’s founding ideas came from the Scottish Enlightenment via a number of Scotsmen who emigrated. I’m not wildly patriotic by nature, but I’m quite proud of the way Scotland pulled itself out of medieval witch-burning into a society that valued education and rationality in a very short space of time. Compulsory education for children was introduced in Scotland long before England and even my very poor forebears seem to have sent their kids to school, and most appeared to have basic literacy.

Oops; sorry. Lecture over!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, I did not know any of that. You should be proud! I am going to have do some reading about Scotland. My parents traveled there years ago and thought it was beautiful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a shame you didn’t get all your answers from that book, but what you learned just might lead you to the answer, especially about Milton.

LikeLike

I am not sure how it can. There were no death certificates, and the one line newspaper announcement of his death gave no explanation. I think I’ve hit the end of the line. But reading the book was nevertheless really helpful and interesting on other aspects of Jacob’s life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I second what Su said. You do a great job including historically relevant details. I did not remember ever learning about the Johnstown flood, what a tragedy! I wish I had an answer about the WWI sign. I wonder if possibly someone next to him should have it posted by their headstone and it was moved accidentally?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think that’s what happened—that it was moved there by mistake. Neither Jacob nor any of his sons were injured or killed or even served overseas during WWI. Thank you!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was worth the effort to track down the book and weave the information into your story. I’m sure it helped you to imagine what life was like.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It really did, and it gave me some details I’d never have found elsewhere about Jacob and his family. But sadly it did not help me find out who Ella’s mother was…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love learning about what life was like for my ancestors. And even more rewarding when you can put a picture to it. My dad would have said “I want to VISUALIZE it”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is real truth to the expression that a picture is worth a thousand words.

LikeLike

What a great post, excited to read about their children! Loved the picture of the Johnstown and especially enjoyed seeing Beth Zion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much, Sharon! It was an interesting one to research and write.

LikeLike

I would have liked to meet Marcus Bohm. The 20 foot sign outside his store has piqued my interest in his marketing techniques! Not only did that sign stand out it got people talking. In this way they became an unpaid form of advertisement for his shop.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great point, EmilyAnn! Thanks so much for your thoughts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What happened was so sad. It’s good you go so far into the past to bring the data together before these connections become too distant. The younger generation might not make the connections you’re doing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It fascinates me, and I feel privileged to be able to honor these people.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re putting your time to excellent use and for a worthwhile purpose.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As are you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Jacob Katzenstein’s Second Family | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Reading about the flood in David McCullough’s book gave me nightmares.

LikeLike

I need to get that book.

LikeLike

It was so suspenseful even knowing all that was going to happen.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The Goldschmidts Come to America | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Found this while searching for items about Rabbi Max Moll, my 2x-great-grandfather. His daughter (my great-grandmother) lived in Titusville, PA. I’m not aware of any family in Johnstown, so why Max was there for the High Holidays is a small mystery. Anyway, I very much enjoyed your account.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Probably because they needed a rabbi and he needed work! Even today there are rabbis and cantors who travel on the holidays to lead services for congregations who need clergy. Small world! Maybe for Max it was a way to be closer to his daughter for the holidays?

LikeLike