This is probably the most moving discovery yet for me personally. I am so excited that I don’t know where to start. This story involves the Brotman family and the Ressler family AND the Rosenzweig family and the Goldschlager family. It’s the final piece of the puzzle about how my grandparents met. It came as a posthumous gift from my much beloved Aunt Elaine, who truly was not only our family matriarch, but also our family historian. Aunt Elaine, you always wanted to tell me these stories, and I was too young and dumb to care. I know you would be so happy that I am finally interested and recording them for all time.

Fortunately, someone was interested in her stories back then. It seems that not only did my brother listen to my aunt, so did my cousin Jody’s husband Joel, my aunt’s son-in-law. He interviewed her about the family and took careful notes. Jody and Joel just found his notes while going through some boxes in their house, and Jody emailed them to me. There is so much information in there that it will take me a while to digest it all and write it up for the blog. Joel’s notes cover stories and anecdotes about the family and reveal some new things as well as things we now know but that I did not know a year ago. But here’s the story that made me say out loud, “Oh, my God!” And then to stop and sit in amazement.

You may recall that a while back I wrote a post about how various members of my family met their spouses, including my grandmother and grandfather. I wrote: “My grandfather Isadore supposedly saw my grandmother sitting in the window of her sister Tillie’s grocery store in Brooklyn and was taken by her beauty.” That was the family story passed down the generations.

When I wrote about this story recently, what I couldn’t figure out was what my grandfather was doing in Brooklyn. He had always lived in East Harlem since arriving in New York and did not live or work in Brooklyn in 1915. So what would have brought him to Brooklyn from East Harlem when he first saw my grandmother?

The answer is revealed in the notes Jody and Joel just sent me. The story begins with my aunt telling Joel that my grandmother Gussie Brotman used to go to her sister Tillie’s grocery store after school.![]() In case you cannot read that, it says, “After school on Friday Gussie would go to Tillie’s house in Brooklyn at her grocery store.”

In case you cannot read that, it says, “After school on Friday Gussie would go to Tillie’s house in Brooklyn at her grocery store.”

In 1915 Tillie and Aaron were living at 1997 Pacific Street in Brooklyn. As Joel’s notes continue:

“Isidore Goldschlager visiting a cousin who lived down the street from the grocery store. As he got off the trolley he saw Gussie on milk box and said to his cousin there is a very beautiful girl. Isadore said he wants to meet her.” (emphasis added)

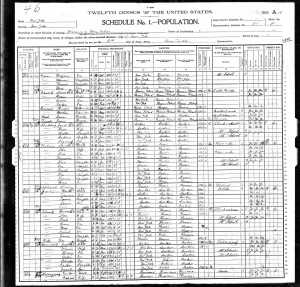

In 1915, the Rosenzweigs were living at 1914 Pacific Street, right down the block from 1997 Pacific Street where Tillie and Aaron Ressler lived. When I wrote that post back on February 5, I did not yet know about Gustave Rosenzweig and his family. I had no idea that my grandfather had cousins living in Brooklyn on the same street where my grandmother was living.

So the cousin that my grandfather was visiting was one of the sons of Gustave Rosenzweig. In 1915, Abraham was 26, Jacob was 21, and Joseph was 17. Abraham and Jacob were in the Navy, and Joseph was working as a driver’s helper. My grandfather was 27 in 1915, so my guess is that he was hanging out with Abraham, who was closest to him in age.

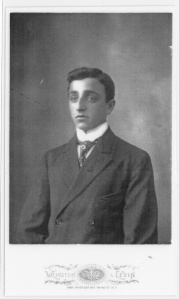

I have wondered whether my grandfather ever saw these cousins once they all got to NYC, whether he knew them well. Well, obviously he did. If he had not been close to them, he would never have come to Brooklyn. He would never have seen that beautiful red haired woman sitting on the milk box. And this would never have happened:

And if that hadn’t happened, then my Aunt Elaine and my Uncle Maurice and my mother would never have been born, and then all my first cousins and my siblings and I would never have been born.

And if that hadn’t happened, then my Aunt Elaine and my Uncle Maurice and my mother would never have been born, and then all my first cousins and my siblings and I would never have been born.

That little stroll down Pacific Street brought the Rosenzweig/Goldschlager family together with the Brotman family and thus created my family. How could this not be my favorite story ever?

This is another one of those moments when all the time spent studying census reports pays off. If I had not found the 1915 census reports for the Resslers and the Rosenzweigs, I would never have known they lived down the street from each other. If I hadn’t looked at all those other documents, I would never have learned about my grandfather’s cousins and his uncle Gustave. If I hadn’t started this blog, Jody and Joel might never have found these notes in their boxes of papers and provided the last piece of the puzzle. If Joel hadn’t listened to his mother-in-law, we wouldn’t have her memories and stories to tie it all together. It should remind us all to ask questions and take notes and listen to our parents, our aunts and uncles, and our grandparents so that we can learn everything we can while we can.

Thank you, Jody and Joel. Thank you, Aunt Elaine. Thank you, Uncle Gustave, for moving to Brooklyn. Thank you, Aunt Tillie, for taking my grandmother to Brooklyn. And thank you, Abraham Rosenzweig, for taking my grandfather for that walk down Pacific Street so that he could meet and marry my grandmother.