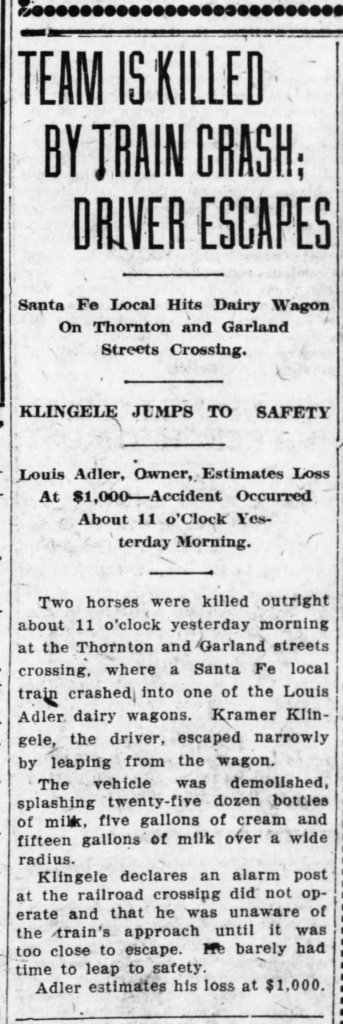

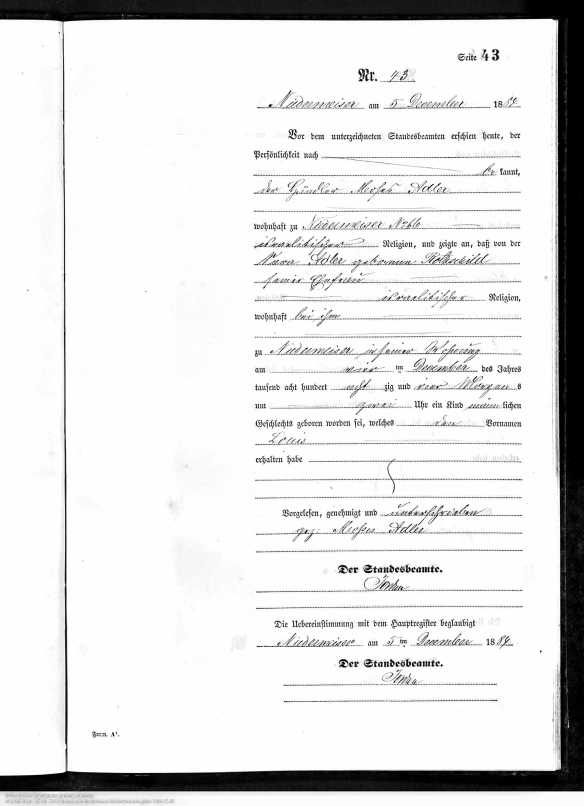

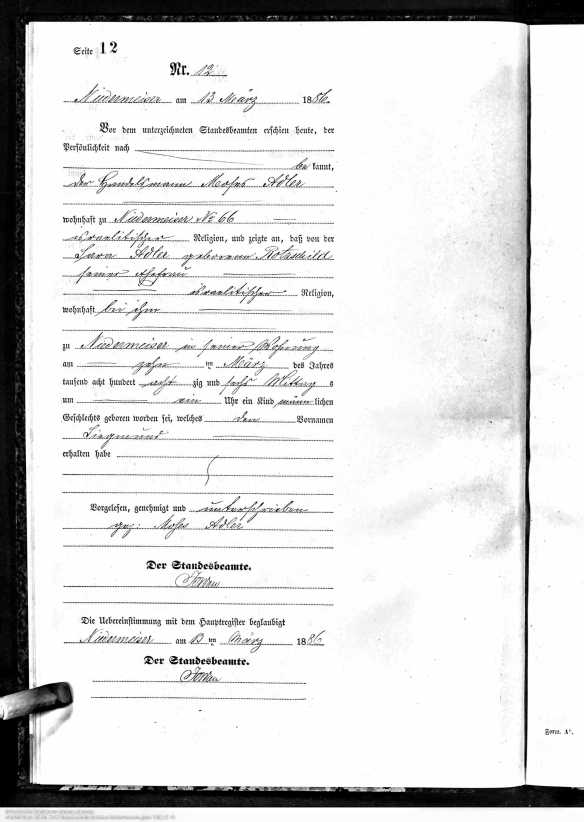

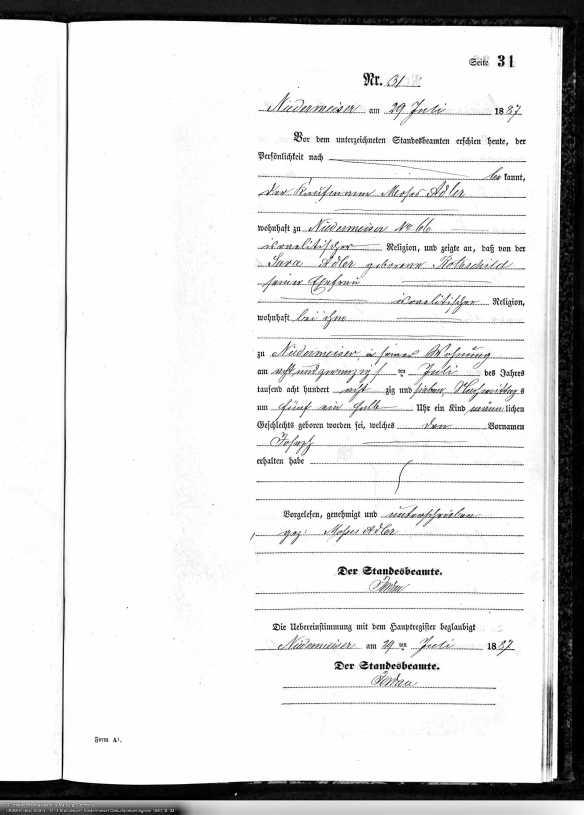

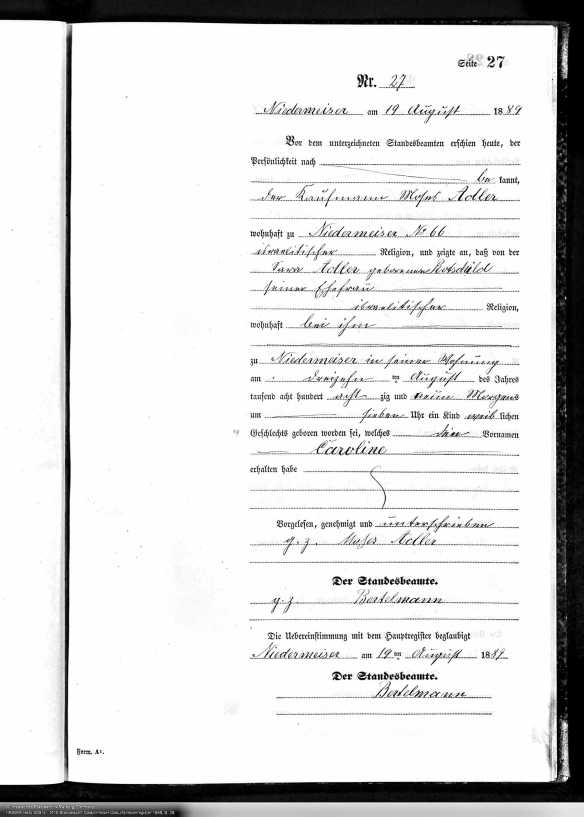

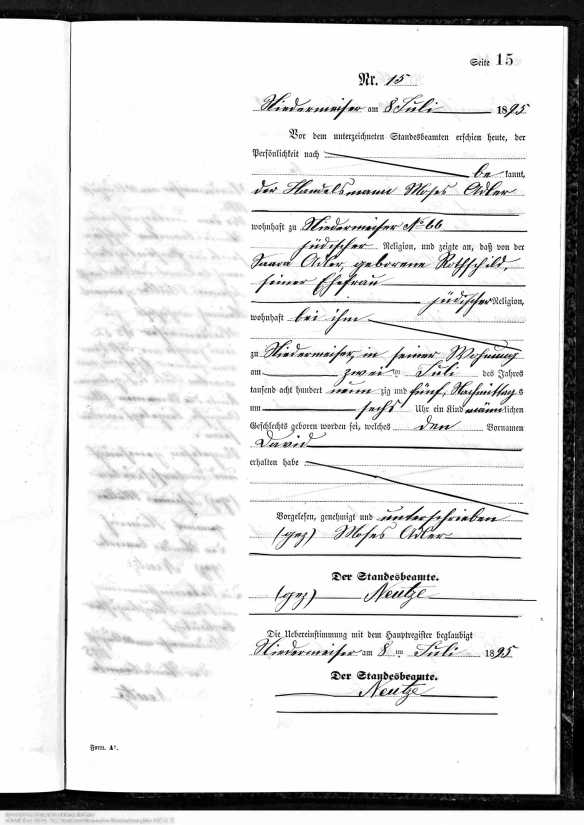

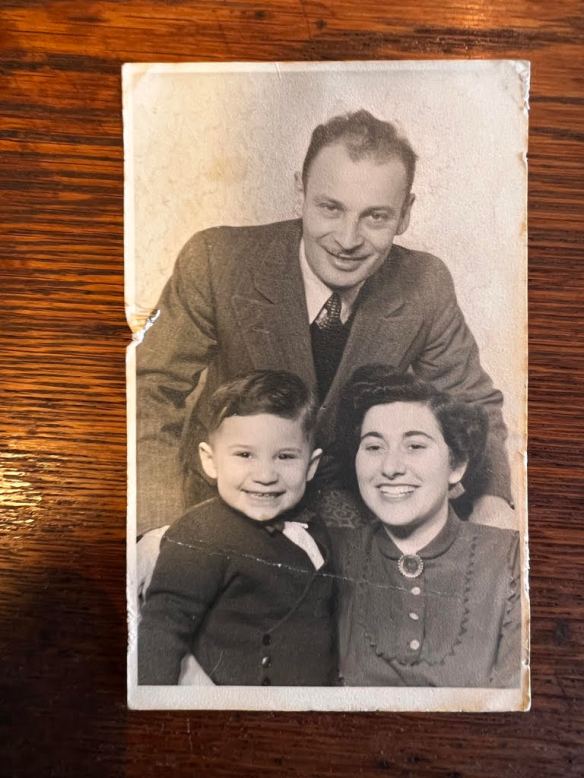

Compared to the rather tumultuous life of his older brother Louis, the life of Sara Rothschild and Moses Adler’s second child Sigmund seems relatively uneventful, but not without its own drama. And it started even earlier in Sigmund’s life. He was sent off at the age of twelve to live with an uncle in the United States; he arrived even earlier than his older brother Louis. As with Louis, who also immigrated as a teenager, I am very curious as to what would lead a parent to allow a child to leave home and cross the ocean at such a young age. But I don’t have an answer.

Sigmund was born on March 10, 1886, and immigrated to the US in 1898, according to numerous census records including the 1900 census taken just two years later. On that census Sigmund was living in Lexington, Kentucky with his uncle Louis Adler, his father’s brother (not Sigmund’s own same-named brother), a shoe merchant. Sigmund was in school and had been listed as an honor student the year before at the Dudley Public School in Lexington.1

Sigmund Adler 1900 US census, Year: 1900; Census Place: Lexington Ward 4, Fayette, Kentucky; Roll: 519; Page: 10; Enumeration District: 0022, Ancestry.com. 1900 United States Federal Census

By 1910, Sigmund had left his uncle’s home and Lexington, Kentucky, behind and was living in Madison, Wisconsin. He was living as a lodger with an unrelated family and listed no occupation. I was puzzled as to what had brought him to Wisconsin so looked for him in the newspapers.com database to see if there were any articles that shed light on that question.2

I found several articles that provided the answer. Sigmund had left Kentucky to attend Beloit College in Beloit, Wisconsin, and then the University of Wisconsin, which is in Madison, Wisconsin. After graduating he was hired by the YMCA in Kenosha, Wisconsin, to be the Assistant Secretary and Boys’ Secretary; as described in the paper, he would be in charge of clerical matters, but primarily responsible for programming for boys at the Y.3 The article below (click and zoom in to read) discusses Sigmund’s involvement in and commitment to programming for boys at the Y during his time at the university.

A later article further detailed Sigmund’s expected responsibilities. “There will be meetings for boys at which interesting topics will be discussed and an effort will be made to have the boys take up natural history with long walks into the country to follow up on this work. Secretary Adler is full of enthusiasm and full of plans for the boys and it is pretty certain that the directors will give him free rein to carry out these plans.”4

In February 1912, Sigmund spoke at a local church; his talk was titled, “The Foreigners within our Gates.” The newspaper commented that “Mr. Adler came to this country as an emmigrant [sic] when he was fifteen years of age [actually twelve]. He worked hard and earned enough money to pay his way through the University of Wisconsin and now holds a responsible position.”5

Six months later Sigmund announced that he would be leaving the Kenosha YMCA for a similar position in Richmond, Virginia. The local paper bemoaned his impending departure, commenting on all the good work he had done:6

[H]is work for boys in this city has attracted attention among association men all over the country. No more popular leader of boys ever came to Kenosha. His work has made the YMCA the social headquarters for the boys of the city and he has brought a big interest in this work to the boys.

The article then listed numerous projects that Sigmund had successfully initiated and led. It also pointed out that Sigmund would have preferred staying in Kenosha, but because of plans for building a new building, “there is grave doubt as to whether or not this work can be continued during the coming year….”7 There was even a farewell dinner for Sigmund attended by a hundred boys.8

Sigmund was still affiliated with the Richmond YMCA in March 1913 when he came to Ishpeming, Michigan, to speak at a boys’ conference there.9 But not long afterward he must have taken a job at the Y in Ishpeming because when he married Ethel Farrill of Kenosha on August 14, 1913, the newspaper story about their wedding noted that Sigmund was now “in charge of YMCA work” in Ishpeming, Michigan.10

Ethel Farrill was the daughter of Reverend Edgar Thomas Farrill and Mary Alice Fenner of Milwaukee, Wisconsin; she was born in Hopkinton, New Hampshire, on April 28, 1885.11 Ethel was a graduate of Smith College and had been teaching in the schools in Kenosha, Wisconsin.12

Sigmund and Ethel had a baby boy named Edgar Farrill Adler on August 27, 1914, in Ishpeming, Michigan, but sadly the baby died a month later on September 28, 1914, from congenital heart disease. Although the name on the death record is Randall Adler and at first I thought Sigmund and Ethel lost two babies born on August 27, 1914, I could find no birth record for Randall and no death record for Edgar. A newspaper article mentioned only one baby. So either Sigmund and Ethel changed the baby’s name (unlikely) or the person filling out the death certificate misheard the baby’s name. 13

Edgar Farrill Adler birth record, Michigan Department of Health and Human Services; Lansing, MI, USA; Michigan Birth Records, 1867-1920, Reference Number: 1-316, Michigan, U.S., Birth Records, 1867-1914

Death record for son of Sigmund Adler and Ethel Farrill, Michigan Department of Community Health, Division for Vital Records and Health Statistics; Lansing, Michigan; Death Records

199: Lenawee-Missaukee, 1914, Ancestry.com. Michigan, U.S., Death Records, 1867-1952

Sigmund and Ethel later adopted a baby boy and named him Edgar Thomas Adler. He was born in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, on April 3, 1917.14

Sigmund registered for the World War I draft on September 12, 1918, in Ishpeming, Michigan. He listed his occupation as “social welfare” for the Cleveland-Cliffs Mining Company.

Sigmund Adler World War I draft registration, Registration State: Michigan; Registration County: Marquette County, Draft Card: A, Ancestry.com. U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918

By 1920, however, Sigmund and his family had relocated again, this time to Hartford, Connecticut, where Sigmund was once again working for the YMCA.15 He finally became a naturalized citizen of the United States on October 25, 1921.16 And appropriately enough his job with the Hartford Y was the secretary of Americanization. Sigmund gave many speeches on the subject and also supervised a program where local volunteers would go into the factories to teach employees about the process of “Americanization.”17

Sigmund returned to working with young people by 1925 when he was a teacher and a guidance counselor in the public high school in Hartford.18 On the 1930 US census, he listed his occupation as a public school teacher; he and Ethel and Edgar were living in Rocky Hill, Connecticut.19 They were still living in Rocky Hill in 1940, and Sigmund continued to teach at a public school.20

Their son Edgar, now 23, was working as a laborer in 1940.21 His World War II draft registration filed later that year revealed that Edgar was working for the Royal Typewriter Company in Hartford and was living at home in Rocky Hill. He enlisted on February 12, 1941, and was discharged with the rank of captain in the US Army on December 26, 1945.22 He served with the Fifth Army in Italy during World War II, earning a Bronze Star and the European African Middle Eastern Service Medal.23

Edgar Adler World War II draft registration, National Archives at St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; Wwii Draft Registration Cards For Connecticut, 10/16/1940-03/31/1947; Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147; Box: 2, Ancestry.com. U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947

Edgar married Edith Constance Gilbert on July 3, 1943, in Augusta, Georgia.23 She was born in September 6, 1923, in Rocky Hill, Connecticut, to Harry Gilbert and Gertrude Codaire.24 They would have two children born in the 1940s. Edgar at some point earned a degree from Wesleyan University in Connecticut.

Sadly, Ethel Farrill Adler died on June 12,1944, in Rocky Hill, before she would know her grandchildren. She was 59 years old.25

Sigmund remarried the following year on February 12, 1945, in Bangor, Maine. His second wife was Alice Jennison,26 born on December 15, 1894, in Bangor, to William Jennison and Florence Whitney.27 She had been previously married and was employed as a secretary to an attorney in Bangor.28

In 1950 Sigmund and Alice were living in Rocky Hill, Connecticut, and neither listed an occupation on the census record. Sigmund was now 64 years old and had retired.29 His son Edgar was also living in Rocky Hill in 1950 with his wife Edith and their children; Edgar was working as the manager of a concrete plant.30

Sigmund Adler died on March 10, 1968, in Rocky Hill, Connecticut. His obituary identified him as “the first guidance counselor of the state,” having served as a guidance counselor at Hartford High School for 27 years, retiring in 1948. He was also active in several civic organizations and in 1962 had been named Man of the Year by B’nai Brith, which surprised me because nothing in Sigmund’s life in the US indicated any connection to Judaism. In fact, his memorial service was at the Rocky Hill Congregational Church.31 Sigmund’s second wife Alice survived him by 26 years. She died at the age of 99 on May 10, 1994, in Rocky Hill.32

Sigmund’s son Edgar died on March 22, 2005, in Hyannis, Massachusetts, not far from where I now live. He was 87 years old. According to his obituary, “[h]e was employed as a boat captain in the charter fishing industry for 25 years prior to retiring in 1979.”33 His wife Edith died twelve years later on January 15, 2017. She was 93 and had been a registered nurse.34 Edgar and Edith were survived by their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

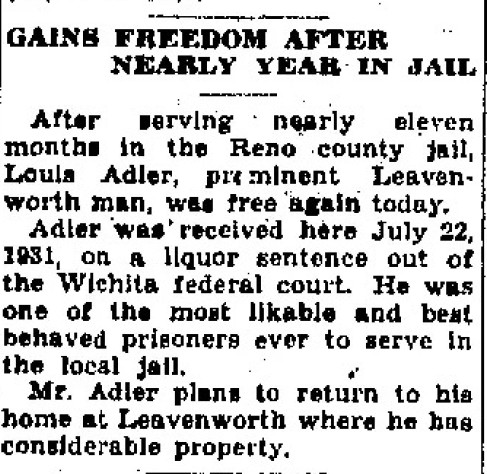

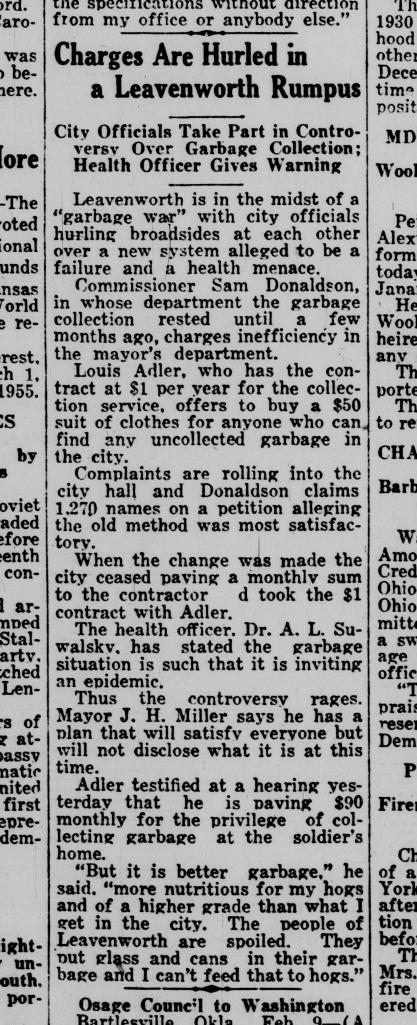

Sigmund Adler’s story stands in stark contrast to that of his older brother Louis, despite the fact that both came as boys to America without their parents. Louis had a life filled with conflict, but like Sigmund, had a long marriage. Sigmund, on the other hand, lived a life that was based on education and service, and although he moved around a lot early on, he lived most of adult life in Rocky Hill, Connecticut, teaching and helping young people find a successful path in life.

As with Louis, I will always wonder why Sara Rothschild and Moses Adler sent Sigmund off to the United States when he was so young. Perhaps in this case they saw his intelligence and his potential and believed his opportunity for success would be greater in the United States than it would have been in a small town in Germany. He certainly found that success.

And now we turn to the third son of Sara and Moses, who also came to the United States when he was quite young. Let’s see what paths his life took. Would they be more like that of his brother Louis or that of his brother Sigmund?

- “Honors for February,” Lexington (KY) Herald-Leader, February 22, 1899, p. 2. ↩

- Sigmund Adler, 1910 US census, Year: 1910; Census Place: Madison Ward 5, Dane, Wisconsin; Roll: T624_1708; Page: 3a; Enumeration District: 0061; FHL microfilm: 1375721, Ancestry.com. 1910 United States Federal Census ↩

- “To Boost Boy’s Work,” Kenosha (WI) News, February 16, 1911, p. 2. ↩

- “Will Keep Boys Busy,” Kenosha (WI) News, February 21, 1911, p. 1. ↩

- “Speaks at Church,” The Journal Times (Racine, WI), February 26, 1912, p. 7. ↩

- “Going to Richmond,” Kenosha (WI) News, August 27, 1912, p. 4. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Kenosha (WI) News, September 4, 1912, p. 5. ↩

- “Delegates Leave Friday to Attend Boys’ Meet,” The Calumet (MI) News, March 26, 1913, p. 5. ↩

- “Miss Farrill Weds,” Kenosha (WI) News, August 15, 1913, p. 5. See also Sigmund Adler, Marriage Date 14 Aug 1913, Marriage County Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA, Spouse, Ethel A Farrill, Wisconsin Historical Society; Madison, WI, USA; Wisconsin Marriage Records 1907-1939, Ancestry.com. Wisconsin, U.S., Marriage Records, 1820-2004 ↩

-

Ethel Alice, Gender, Female, Race White Birth Date 28 Apr 1885 Birth Place

Hopkinton, New Hampshire, USA, Father Edgar T Farrell. Mother M Farrell, Birth Certificates, 1631-1919; Archive: New Hampshire Department of State; Location: Concord, New Hampshire; Credit: The Original Document May Be Seen At the New Hampshire Department of State; Ancestry.com. New Hampshire, U.S., Birth Records, 1631-1920 ↩ - See Note 10, supra. ↩

- See images above. Kenosha (WI) News, September 30, 1914, p. 5 (news report of the death of Edgar Farrill Adler). ↩

- See Edgar Adler on the 1920 US census, where he is described as their adopted son. Year: 1920; Census Place: Hartford Ward 10, Hartford, Connecticut; Roll: T625_184; Page: 1B; Enumeration District: 124, Ancestry.com. 1920 United States Federal Census. Edgar Thomas Adler [Edgar T Adler], Gender Male, Race White, Birth Date 3 Apr 1917, Birth Place Fondulac, Wisconsin, Death Date 22 Mar 2005, Father Sigmund Adler, Mother Ethel Farrill, SSN 049015785, Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007 ↩

- Sigmund Adler and family, 1920 US census, Year: 1920; Census Place: Hartford Ward 10, Hartford, Connecticut; Roll: T625_184; Page: 1B; Enumeration District: 124, Ancestry.com. 1920 United States Federal Census ↩

- Sigmund Adler, Naturalization Age 35, Record Type Naturalization, Birth Date 10 Mar 1886, Birth Place Germany, Naturalization Date 25 Oct 1921, The National Archives in Washington, DC; Washington, DC; Indexes to Naturalization Petitons For United States District Courts, Connecticut, 1851-1992 (M2081); Microfilm Serial: M2081; Microfilm Roll: 1, Ancestry.com. U.S., Naturalization Record Indexes, 1791-1992 (Indexed in World Archives Project) ↩

- “YMCA Planning to Educate Aliens in City Factories,” Hartford (CT) Courant, September 11, 1919, p. 16. ↩

- “Older Girls Hold Annual Conference,” Hartford (CT) Courant, April 18, 1925, p. 9. ↩

- Sigmund Adler, 1930 US census, Year: 1930; Census Place: Rocky Hill, Hartford, Connecticut; Page: 18A; Enumeration District: 0207; FHL microfilm: 2340003, Ancestry.com. 1930 United States Federal Census ↩

-

Sigmund Adler, 1940 US census, Year: 1940; Census Place: Rocky Hill, Hartford, Connecticut; Roll: m-t0627-00506; Page: 12A; Enumeration District: 2-199,

Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census ↩ - See Note 20, supra. ↩

- Edgar T. Adler, National Archives at College Park; College Park, Maryland, USA; Electronic Army Serial Number Merged File, 1938-1946; NAID: 1263923; Record Group Title: Records of the National Archives and Records Administration, 1789-ca. 2007; Record Group: 64; Box Number: 03303; Reel: 52, Ancestry.com. U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946 ↩

- “Adler-Gilbert,” Hartford (CT) Courant, July 30, 1943, p. 11. ↩ ↩

-

Edith C Adler, Death Age 93, Birth Date 6 Sep 1923, Death Date 15 Jan 2017

Interment Place Bourne, Massachusetts, USA, Massachusetts National Cemetery

Section D, Row 2, Plot D30, National Cemetery Administration; U.S. Veterans’ Gravesites, National Cemetery Administration. U.S., Veterans’ Gravesites, ca. 1775-2019; Edith Adler, 1930 US Census, Year: 1930; Census Place: Rocky Hill, Hartford, Connecticut; Page: 22A; Enumeration District: 0207; FHL microfilm: 2340003, Ancestry.com. 1930 United States Federal Census ↩ - Ethel Adler, Death Date 12 Jun 1944, Death Place Rocky Hill, Connecticut, USA, Connecticut Department of Public Health; Hartford, Connecticut, USA, Ancestry.com. Connecticut, U.S., Death Index, 1917-2017 ↩

- Sigmund Adler, Gender Male, Residence Rocky Hill, CT, Spouse’s Name Alice Jennison, Spouse’s Gender Female, Spouse’s Residence Bangor, ME, Marriage Date 5 Oct 1945, Marriage Place Maine, USA, Ancestry.com. Maine, U.S., Marriage Index, 1892-1996, Original data: Maine State Archives. Maine Marriages 1892-1996 (except 1967 to 1976). ↩

- Alice Jennison, Gender Female Birth Date 15 Dec 1895 Birth Place Bangor, Penobscot, Maine, USA, Father William A Jennison. Mother Florence Whitney, Maine State Archives; Cultural Building, 84 State House Station, Augusta, ME 04333-0084; 1892-1907 Vital Records; Roll Number: 29, Ancestry.com. Maine, U.S., Birth Records, 1715-1922 ↩

-

Alice Jennison, Gender Female, Age 27, Birth Date abt 1894, Birth Place Bangor, Marriage Date 5 Nov 1921, Marriage Place Bangor, Kennebec, Maine, USA

Father William A Jennison, Mother Florence Whitney, Spouse Miles F Ham, Maine State Archives; Cultural Building, 84 State House Station, Augusta, ME 04333-0084; 1908-1922 Vital Records; Roll Number: 24, Ancestry.com. Maine, U.S., Marriage Records, 1713-1922 ↩ - Sigmund Adler, 1950 US census, National Archives at Washington, DC; Washington, D.C.; Seventeenth Census of the United States, 1950; Year: 1950; Census Place: Rocky Hill, Hartford, Connecticut; Roll: 3568; Page: 19; Enumeration District: 2-205, Ancestry.com. 1950 United States Federal Census ↩

- Edgar T. Adler, 1950 US census, National Archives at Washington, DC; Washington, D.C.; Seventeenth Census of the United States, 1950; Year: 1950; Census Place: Rocky Hill, Hartford, Connecticut; Roll: 3568; Page: 14; Enumeration District: 2-206, Ancestry.com. 1950 United States Federal Census ↩

-

Sigmund Adler, Gender Male, Birth Date 10 Mar 1886, Death Date 15 Mar 1968

Claim Date 20 Dec 1965, SSN 048362456, Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007; “Sigmund Adler Dies; Guidance Counselor,” Hartford (CT) Courant, March 11, 1968, p. 8. ↩ - Alice Adler death notice, Hartford (CT) Courant, May 12, 1994, p. 90. ↩

-

Edgar T. Adler, Social Security Number 049-01-5785, Birth Date 3 Apr 1917

Issue year Before 1951, Issue State Connecticut, Last Residence 02675, Yarmouth Port, Barnstable, Massachusetts, Death Date 22 Mar 2005, Social Security Administration; Washington D.C., USA; Social Security Death Index, Master File, Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014; Edgar T. Adler, The Barnstable (MA) Patriot, April 1, 2005, found at https://www.barnstablepatriot.com/story/news/2005/03/31/obituaries-4-1-05/33017465007/ ↩ - Edith Constance Adler obituary, found at https://www.dignitymemorial.com/obituaries/sandwich-ma/edith-adler-7253066 ↩