This will be my last post before we leave on our trip. I wanted to leave on a high note with a new discovery—a Brotman line I’d not discovered until the last week or so. Perhaps this is a good omen for what I might find when in Poland. I might post a bit while away—depends on internet access, time, and energy. But I will report on the trip either as it unfolds or after I return, so stay tuned.

*********

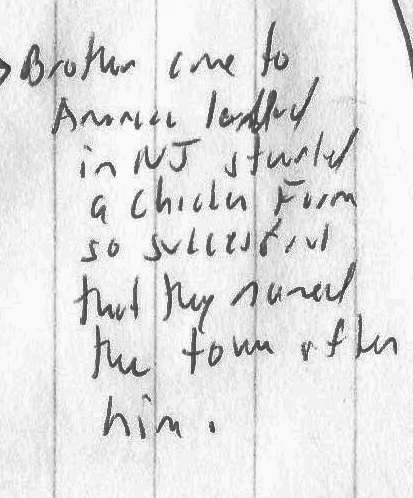

In my last post I reported on the conflicting results of my search through the records of the families of Moses and Abraham Brotman of Brotmanville, New Jersey. I was looking for any shred of evidence that might reveal where they, and thus perhaps my great-grandparents, had lived in Europe. What I found was that some records said Moses was born in Austria, some said Russia. Same for Abraham. And not one record named a town or city. Thus, I had not gotten any closer to any answers.

But while reviewing the documents I had and checking and double-checking my tree, I did find something somewhat anomalous. In doing my initial research of Moses’ family, I had not been able to find them on the 1920 census, as I mentioned in my last post. In trying to find the family, I had searched for each of the children separately, and I had found a Joseph Brotman living in Davenport, Iowa, according to the 1915 Iowa state census. I admit that I had not looked very carefully (BIG mistake) and had jumped to the conclusion that Moses’ son Joseph had been shipped out to Iowa to live with another family since I couldn’t find Moses or Ida or any of the siblings listed on that census. (This is one reason I keep my tree private on Ancestry—I’d hate to mislead someone else while I am doing preliminary research.)

But in now reviewing my original preliminary research, this just struck me as strange. So I went back to look more carefully. First, I pulled up the census record for Joseph. Instead of being a list or register as with other census reports, Iowa had separate cards for each resident. Here is the one for Joseph Brotman:

![Joseph Brotman 1915 Iowa census Ancestry.com. Iowa, State Census Collection, 1836-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007. Original data: Microfilm of Iowa State Censuses, 1856, 1885, 1895, 1905, 1915, 1925 as well various special censuses from 1836-1897 obtained from the State Historical Society of Iowa via Heritage Quest](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/joseph-brotman-ben-1915-iowa-census.jpg?w=584&h=400)

Joseph Brotman 1915 Iowa census

Ancestry.com. Iowa, State Census Collection, 1836-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007.

Original data: Microfilm of Iowa State Censuses, 1856, 1885, 1895, 1905, 1915, 1925 as well various special censuses from 1836-1897 obtained from the State Historical Society of Iowa via Heritage Quest

But this time I took the next step—were there other Brotmans in Davenport on that census? First I saw a Lillian Brotman. I thought, “Hmmm, maybe two siblings were sent to Iowa?” Remember—Moses had a daughter named Lillian, as did Abraham. So I looked at Lillian’s entry in the 1915 census.

![Lillian Brotman 1915 Iowa census Ancestry.com. Iowa, State Census Collection, 1836-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007. Original data: Microfilm of Iowa State Censuses, 1856, 1885, 1895, 1905, 1915, 1925 as well various special censuses from 1836-1897 obtained from the State Historical Society of Iowa via Heritage Quest.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/lillian-brotman-ben-1915-iowa-census.jpg?w=584&h=396)

Lillian Brotman 1915 Iowa census

Ancestry.com. Iowa, State Census Collection, 1836-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007.

Original data: Microfilm of Iowa State Censuses, 1856, 1885, 1895, 1905, 1915, 1925 as well various special censuses from 1836-1897 obtained from the State Historical Society of Iowa via Heritage Quest.

I decided to go through the cards in the census by flipping backwards from Joseph’s card and then found several other Brotmans at the same address: Albert (2), Eva (37), and May (10). May also had been born in New Jersey, Albert in Iowa, and Eva in Russia. Who were these people? Were they related to MY Brotmans in some way? I assumed Eva was the mother of these four children, but who was the father? And where was he?

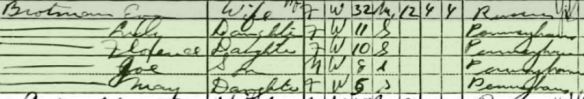

So I searched for the family by using Eva’s names and the names of the children, and I found them on the 1910 census living in Philadelphia. The husband’s name was Bennie, wife Eva (32), and four children: Lily (11), Florence (10), Joe (8), and May (6). These ages lined up with the ages of the children on the Iowa census five years later, but the census record said these children were born in Pennsylvania, not New Jersey. The father, Bennie, was 33, born in Austria with parents born in Russia, and had immigrated in 1894, according to the census. He was a cutter in a clothing business. He and his wife had been married for 12 years or since 1898.

Bennie Brotman 1910 census

Source Citation

Year: 1910; Census Place: Philadelphia Ward 1, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Roll: T624_1386; Page: 11B; Enumeration District: 0019; FHL microfilm: 1375399

What had happened to their daughter Florence? And where had they been in 1900? Were they related to my Brotmans? I first searched for their missing daughter, and I found an entry in the Iowa, Select Deaths and Burials 1850-1990 database:

| Name: | Flora Brotman |

|---|---|

| Gender: | Female |

| Marital Status: | Single |

| Age: | 13 |

| Birth Date: | 1900 |

| Birth Place: | Philadelphia |

| Death Date: | 23 Aug 1913 |

| Death Place: | Davenport, Iowa |

| Burial Date: | 24 Aug 1913 |

| Father: | Ben Brotman |

| Mother: | Eva Siegel |

| FHL Film Number: | 1480948 |

| Reference ID: | p186 r59 |

This document provided me with Eva’s birth name and Flora’s birthplace. I thought that the family must have been living in Philadelphia in 1900 if that is where Flora was born, but I could not find them on the 1900 census living in Philadelphia. I searched again for Flora, and this time found a birth record—not in Philadelphia or even in Pennsylvania, as the death record and 1910 census had reported. Rather, she was born in, of all places, Pittsgrove, Salem County, New Jersey, on July 19, 1900, to Benj. Brotman (born in Austria) and Eva Sigel (born in Russia). Once I saw Pittsgrove, my heart beat a little faster. This more and more seemed like a member of the Brotmanville Brotman family—someone I had not ever located or researched before. Who was he? How was he related, if at all, to Moses and Abraham?

| Name: | Flora Brotman |

|---|---|

| Gender: | Female |

| Birth Date: | 19 Jul 1900 |

| Birth Place: | PIT, Salem County, New Jersey |

| Father’s name: | Benj Brotman |

| Father’s Age: | 24 |

| Father’s Birth Place: | Aug. |

| Mother’s name: | Eve Sigel |

| Mother’s Age: | 22 |

| Mother’s Birth Place: | Russia |

| FHL Film Number: | 494247 |

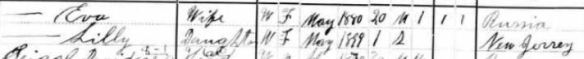

I searched for them on the 1900 census again, but this time in Pittsgrove, New Jersey. It took some doing, but finally found Benjamin listed as Bengeman Brotman, listed at the very bottom of the same page as Moses Brotman, just a few households away. The census reported that he was 24, a cutter, and married for one year. It stated that he and his parents were born in Austria, that he had immigrated in 1888, and that he was a naturalized citizen. At the top of the next page were the listings for his wife Eva and daughter Lilly, just a year old. The other children had not yet been born.

Ben Brotman’s family 1900 census

Year: 1900; Census Place: Pittsgrove, Salem, New Jersey; Roll: 993; Page: 18B; Enumeration District: 0179; FHL microfilm: 1240993

From this census, I knew that Benjamin Brotman had lived in Pittsgrove right near Moses Brotman, had married Eva Siegel and had had at least two children in Pittsgrove before moving to Philadelphia, where they were living in 1910. By 1913, the family was living in Davenport, Iowa, where their daughter Flora died. But where was Benjamin in 1915 when the Iowa census was taken? And was he related to Moses Brotman?

Looking one more time, I found him listed in the 1914 Davenport, Iowa, directory as a peddler, living with his wife Eva at the same address where she and the children were listed in the 1915 Iowa census. I also found him in the 1915 directory at that address, but with no occupation listed, and in the 1918 directory at a new address, 1323 Ripley, the same address given for his son Joseph, listed as a chauffeur, and his daughter Lillian, listed as a bookkeeper. A very similar series of entries appears in the 1919 directory. In both Benjamin still had no occupation listed. If he was living in Davenport in 1914, 1915, 1918 and 1919, why wasn’t he in the Iowa census?

One more search of the I0wa 1915 census produced this result:

![Benjamin Brotman 1915 Iowa census Ancestry.com. Iowa, State Census Collection, 1836-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007. Original data: Microfilm of Iowa State Censuses, 1856, 1885, 1895, 1905, 1915, 1925 as well various special censuses from 1836-1897 obtained from the State Historical Society of Iowa via Heritage Quest.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/ben-brotman-moses-1915-iowa-census-e1431702730184.jpg?w=584&h=360)

Benjamin Brotman 1915 Iowa census

Ancestry.com. Iowa, State Census Collection, 1836-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007.

Original data: Microfilm of Iowa State Censuses, 1856, 1885, 1895, 1905, 1915, 1925 as well various special censuses from 1836-1897 obtained from the State Historical Society of Iowa via Heritage Quest.

But what happened to Ben after 1915? Did he recover? Is that why he appears in the 1918 and 1919 directories? On the 1920 census Ben is listed with Eva and three of their surviving children, Lillian, Joseph, and Albert, and a new son Merle, only four years old. It would seem that Ben had not only recovered, but had returned home and fathered another child.

Benjamin Brotman 1920 census

Year: 1920; Census Place: Rock Island Precinct 4, Rock Island, Illinois; Roll: T625_402; Page: 16A; Enumeration District: 128; Image: 1078

The family was living in Rock Island, Illinois, right across the Mississippi River from Davenport, Iowa. Ben was not employed, but Lillian was a bookkeeper and Joseph a salesman at a general store. Their daughter May was listed on the 1920 census as an inmate at the Institution for Feeble-Minded Children in Glenwood, Iowa, over 300 miles away from Rock Island. She was still there ten years later according to the 1930 census.

English: Downtown Davenport, Iowa looking across the Mississippi River from Rock Island, Illinois (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

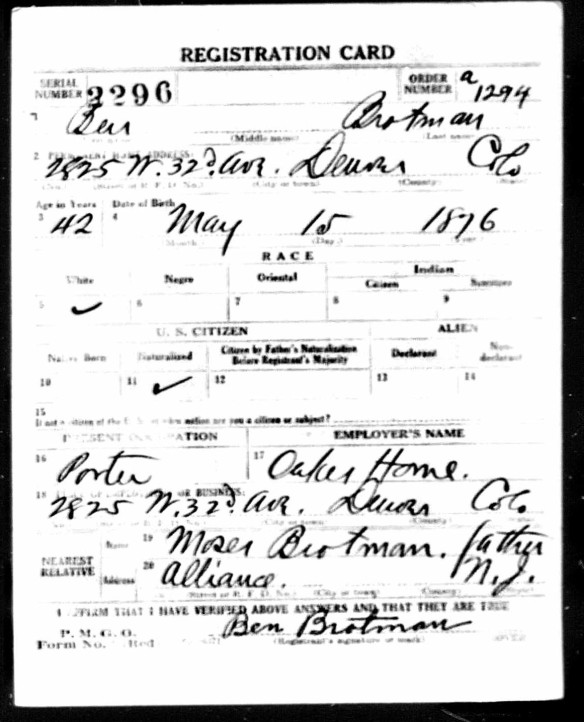

As I followed the family forward into the 1920s, Benjamin seemed to have died or disappeared. In the 1921 Rock Island directory, Eva Brotman is listed as a widow. And in the Illinois, County Marriages 1810-1934 database on FamilySearch, I found a marriage listing for Eva Brotman and Abe Abramovitz on July 26, 1923, in Rock Island. In 1930, Eva was living with her second husband Abe and her two youngest sons, Albert (listed incorrectly as Abe) and Merle (listed incorrectly as Muriel), who were then 18 and 15, respectively. They were all still living together ten years later, according to the 1940 census.

Eva Siegel Brotman Abromovitz and sons 1930 census

Year: 1930; Census Place: Rock Island, Rock Island, Illinois; Roll: 553; Page: 5B; Enumeration District: 0084; Image: 716.0; FHL microfilm: 2340288

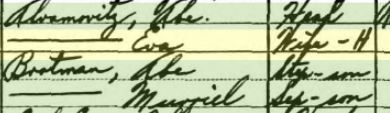

It seemed I had reached the end of the line for Benjamin Brotman, but I had no death record, and I still had no idea whether he was related to me or to the Brotmanville Brotmans. I kept searching for a death record, and instead I found this:

Ben Brotman World War I draft registration

Registration State: Colorado; Registration County: Denver; Roll: 1544482; Draft Board: 1

A World War I registration for a Ben Brotman born in 1876, no birthplace listed, living in Denver, Colorado. I might not have given it much thought but for the name given as his nearest relative: Moses Brotman of Alliance, New Jersey, his father. Moses Brotman of Alliance is the Brotmanville Moses Brotman (Alliance was the name of the community where the Brotmans settled, part of Pittsgrove, now called Brotmanville.). This Ben Brotman was his son. The age fit exactly—the Ben Brotman living in Pittsgrove in 1900 was 24, thus born in 1876, just like the Ben Brotman living in Colorado in 1918, son of Moses. I had no child listed for Moses named Benjamin, and if this was in fact his son, he was born before Moses married Chaya/Ida/Clara Rice. That is, this could be Abraham’s full brother from Moses’ first wife, whose name I did not know.

But could I be sure that this was the Ben Brotman who had lived in Pittsgrove, then Philadelphia, then Davenport, Iowa? And if so, what was he doing in Colorado in 1918 when this draft registration was filed? After all, Ben Brotman, Eva’s husband, had been listed in the 1918 and 1919 Davenport directories.

The draft registration listed the Colorado Ben Brotman as a porter at Oakes Home in Denver. I googled that name and found that Oakes Home in Denver was an institution for patients suffering from tuberculosis. Was Ben really an employee there or was he a patient? There is no indication on his draft registration that he was in poor health and not able to serve in the military. Had he gone there as a patient and recovered sufficiently to be employed but not yet enough to return to Iowa?

As you might imagine, I was now more than a bit confused. If this was the same Ben, had he then returned to Iowa at some point in 1918, been there in 1919 and 1920, and then died by 1921, as Eva’s listing in the 1921 Rock Island directory suggested? I needed to find his death certificate, and I had no luck searching online in Iowa, Illinois, or Colorado. As I’ve done before, I turned to the genealogy village for assistance.

I went to the Tracing the Tribe group on Facebook and found a number of people who volunteered to help me. One person found an entry on Ancestry from the JewishGen Online World Burial Registry for a Bera Brotman who died on January 4, 1922, who was born about 1877, and who was buried at the Golden Hills Cemetery in Lakewood, Colorado. It seemed like a long shot. Was Bera even a man? The birth year was close enough, but if Eva was a widow in 1921, the death date was too late. There was a phone number for a contact person at the cemetery listed on the entry, so I called him.

| Name: | Bera Brotman |

|---|---|

| Birth Date: | abt 1877 |

| Death Date: | 4 Jan 1922 |

| Age at Death: | 45 |

| Burial Plot: | 10-097 |

| Burial Place: | Lakewood, Colorado, United States |

| Comments: | No gravestone |

| Cemetery: | Golden Hill Cemetery |

| Cemetery Address: | 12000 W. Colfax |

| Cemetery Burials: | 3839 |

| Cemetery Comments: | Contact: Neal Price (303) 836-2312 |

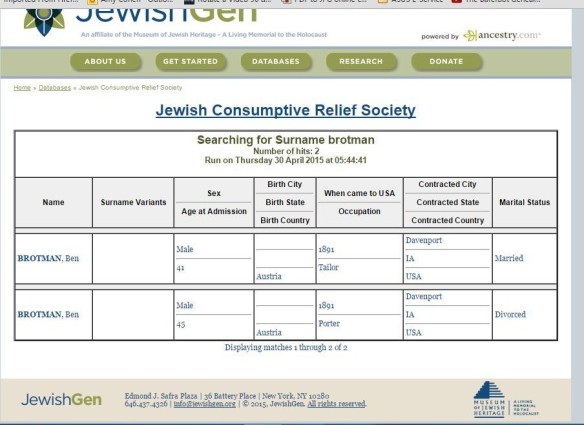

The contact person checked the cemetery records and confirmed the information listed on JOWBR, but gave me one more bit of critical information: Bera’s last residence was the Jewish Consumptive Relief Society in Denver. By googling the JCRS, I found that JewishGen had a database of records from there, and when I searched for Ben Brotman on the JCRS database, I found this record:

This Ben Brotman had to be the one who had been at one time living in Pittsgrove, New Jersey, and then had moved to Davenport, Iowa. This was the Ben who had married Eva and had six children. He had twice been a patient at the JCRS. First, he’d been admitted when he was 41 or in 1917, when he listed his status as married, and then he’d been admitted again when he was 45 or in 1921, when he listed his status as divorced. The pieces were starting to come together. Perhaps Ben had in fact been in Denver in 1917, recovered enough to register for the draft there in 1918, then returned to his family in Davenport sometime in 1918 through 1920. He then had to return to the JCRS in Denver in 1921, where he died in January, 1922. By 1921 he and Eva had divorced, and Eva had listed herself as a widow in the directory, as many divorced women did in those days when divorce was stigmatizing.

I emailed the cemetery contact person and explained that I thought Bera was really Ben, and he agreed to change the records. But I still had some nagging doubts. Was the Ben Brotman who had died in Colorado in January, 1922, and who had lived in Davenport also the one who was the son of Moses Brotman, as indicated on the draft registration? I needed the death certificate to be sure, and perhaps it would also tell me where Ben was born, helping to answer the question that had started me down this path in the first place.

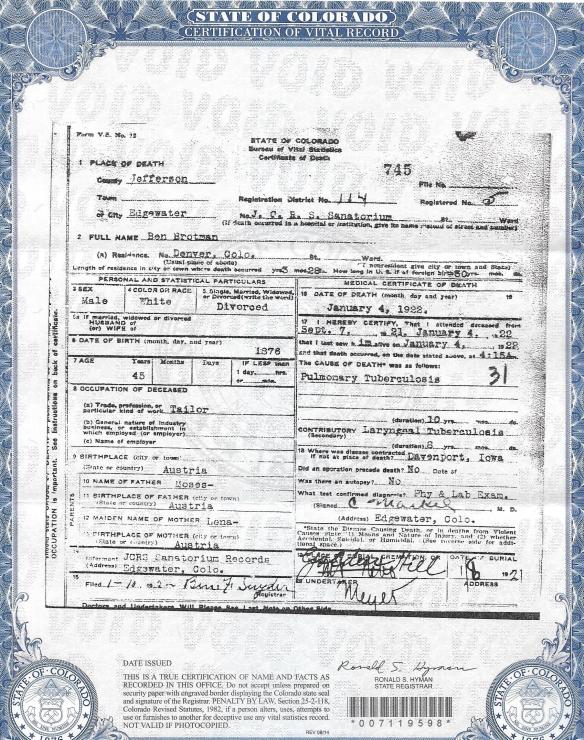

I ordered the death certificate, and it finally arrived just the other day.

Ben Brotman died on January 4, 1922, of pulmonary tuberculosis at the J.C.R.S Sanitorium. He was 45 years old and born in 1876, and he had been a tailor. He had contracted TB in Davenport, Iowa, and had had it for ten years, or since 1912, which would mean around the time the family had moved to Iowa. (That makes me wonder even more whether his daughter Flora had also died of TB, since she died in 1913.) The doctor at JCRS who signed the death certificate said that he had attended Ben since September 7, 1921, which must have been when he was admitted the second time. The certificate stated that Ben had been a Denver resident for three months and 28 days, indicating that he had been elsewhere before returning in September. It also reported his marital status as divorced. Finally, his place of birth was given as Austria, and his parents were also reported to have been born in Austria.

And then the answer I’d been seeking: his father’s name was Moses. This was then most definitely the same Benjamin Brotman I had traced from Pittsgrove to Philadelphia to Davenport to Denver to Rock Island and back to Denver. This was the son of Moses Brotman, my great-grandfather’s brother.

And then the (hopefully accurate) big revelation: his mother’s name was Lena. For the first time I had a record of the name of Moses’ wife prior to Ida/Chaya/Clara Rice. Lena. She very well might have been the mother of Abraham Brotman. I don’t know. There is a big gap between Abraham’s presumed birth year of 1863 and Benjamin’s birth year of 1876. There must have been other children in between, I’d think. Or perhaps Lena was Benjamin’s mother, and Abraham’s mother was an even earlier wife of Moses. But since both Abraham and Benjamin named their first daughters Lillian and at around the same time, I think that both of these girls were named for their grandmother Lena, who must have died before 1884 when Moses married his second wife Chaya.

I made one more look back at the records I had for Moses and for Abraham and realized that I had not re-checked the 1895 New Jersey census. Since it only listed names, not ages or birthplaces, I had not thought it important in my search for where they’d lived in Europe. Moses and his family are listed on the page before Abraham and his family on that census. Abraham is listed with Minnie and their first three children, Joseph, Samuel, and Kittella (presumably Gilbert).

![Abraham Brotman 1895 NJ census Ancestry.com. New Jersey, State Census, 1895 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007. Original data: New Jersey Department of State. 1895 State Census of New Jersey. Trenton, NJ, USA: New Jersey State Archives. 54 reels.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/abraham-brotman-1895-nj-census.jpg?w=584&h=122)

Abraham Brotman 1895 NJ census

Ancestry.com. New Jersey, State Census, 1895 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007.

Original data: New Jersey Department of State. 1895 State Census of New Jersey. Trenton, NJ, USA: New Jersey State Archives. 54 reels.

![Moses Brotman 1895 NJ census Ancestry.com. New Jersey, State Census, 1895 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007. Original data: New Jersey Department of State. 1895 State Census of New Jersey. Trenton, NJ, USA: New Jersey State Archives. 54 reels.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/moses-brotman-1895-nj-census.jpg?w=584&h=202)

Moses Brotman 1895 NJ census

Ancestry.com. New Jersey, State Census, 1895 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007.

Original data: New Jersey Department of State. 1895 State Census of New Jersey. Trenton, NJ, USA: New Jersey State Archives. 54 reels.

Although I was very excited to find this lost Brotman, unfortunately I still don’t have any record identifying a specific town or city where the Brotmanville Brotmans lived in Europe. But soon I will head off to Tarnobrzeg, Poland, the town I still think is the most likely ancestral home of my great-grandparents Joseph and Bessie Brotman.

[1] I found this very strange—did Moses really have another son named Abraham? The Abraham listed on the 1895 New Jersey census was five years old or younger, meaning he was born in 1890 or later. Samuel was born in 1889, but must not yet have turned five; Lily was born in 1892. The only other child born between 1890 and 1894 was Isaac (who became Irving), not Abraham, so I assume this entry on the 1895 census was a mistake and that “Abraham” was really Isaac.

[2] In doing this research I kept tripping over another Brotman family—a family living in Rock Island that owned the theaters in town. However, they do not appear to be related. The patriarch of that family, Jacob Brotman, was born in 1848 in Minsk, Russia, and had lived in London before emigrating to the US sometime after 1901. Since Joseph and Moses were born around the same time but somewhere in Galicia, it seems unlikely that Jacob was a close relative. But anything is possible.