I’ve now completed my research of the American Seligmans, or at least those I know to be related to me. I have added a page with a family tree and descendant chart to the blog that you can find by clicking on the label in the menu box at the top of the page.

For a number of reasons, this has been the easiest branch of the family tree to research. First, I was fortunate to find my cousin Arthur “Pete” Scott, who is the great-grandson of Bernard Seligman and the grandson of Arthur Seligman. He had already done a lot of work on the family history in New Mexico and was very generous in sharing his research and photographs with me. He also had published a great deal of it on the web at vocesdesantafe.com.

Secondly, Bernard and Arthur Seligman were public figures—men who were often written about during their lives in newspapers and after their lives by historians. Their fame made it much easier for me to find sources and information to learn about their lives and the lives of their families. (Although it was easier to find information, it also was a lot more work to read it, digest it, and analyze it all.)

Also, there were not a lot of descendants to trace. Sigmund Seligman never married, James Seligman in England had no children, and Bernard only had three children who lived to adulthood—my great-grandmother Eva and her two brothers James and Arthur.[1] Eva’s family I had already researched in doing the Cohen branch, James had only one child who lived to adulthood, and Arthur had one biological child and a stepdaughter. So compared to the thirteen children of Jacob Cohen, some of whom had over ten children themselves, this was a much smaller family to research.

I still do have work to do, tracing the German Seligmanns and seeing if I can learn what happened to them. That is a task I will continue to work on, but it will be slowed by the inaccessibility of German records and my inability to read German. I am ordering copies of the records I posted about here, but I hope to be able to learn more. Once I know more, I will write about it on the blog.

But for now I will move on from the Seligmans in my writing and begin the next branch of my father’s father’s family, the Nusbaums. As far as I know, there are no famous people on this branch, but time will tell. I am hoping that my cousin Pete will be able to help me here as well since he also is a descendant of Frances Nusbaum Seligman. I have already learned some interesting things about the Nusbaums and am eager to learn more.

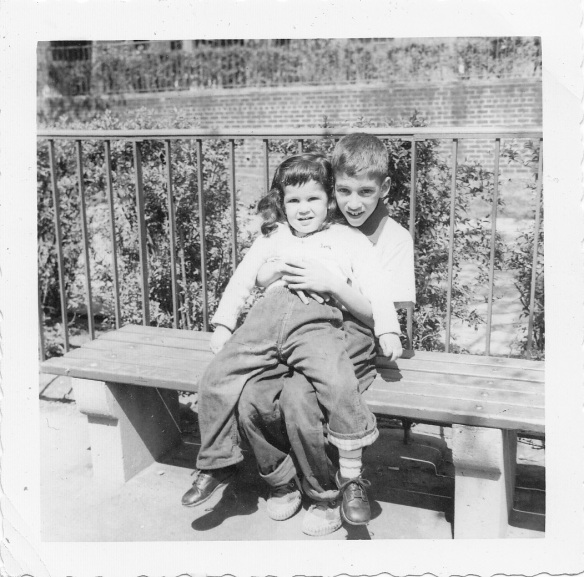

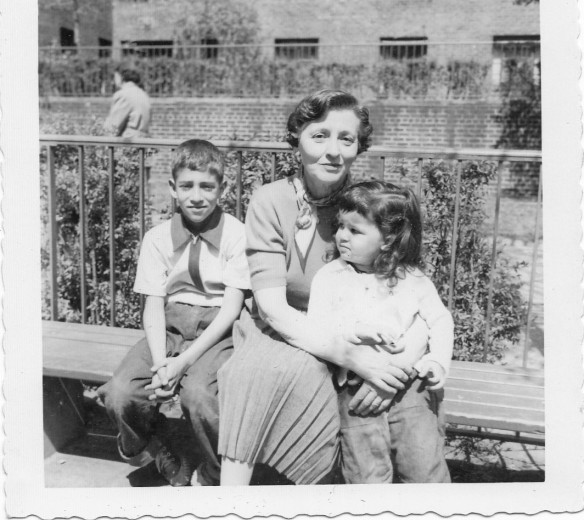

Governor Arthur Seligman, Marjorie, and his sister, my great-grandmother Eva May Seligman Cohen, 1932 Atlantic City

Before I move on from the Seligmans, however, I have a few concluding thoughts about this branch of my family tree. Unlike my Cohen, Goldschlager, Rosenzweig, and Brotman branches, the Seligmans were in the public eye and not able to lead the private lives that my other relatives lived and that most of us live. They were subject to much scrutiny—Bernard was a wealthy merchant and public servant, Arthur a mayor and governor, and Morton a Navy hero. Their actions and character were criticized at times, but each in his own way managed to rise above that criticism. They were loyal, decent and honest men who served their communities with honor.

What the Seligmans share with the rest of my ancestors is the story of Jewish immigrants in general—whether they came in 1850 or 1890 or 1910, whether they came from Germany or England or Romania or Galicia. All came here for a better life, all were brave enough to leave their homes and their families, all took a risk that living in America would be better for them, their families, and their descendants. Some may have come with more than others, some succeeded more than others, but all were undoubtedly better off here than they would have been had they stayed in Europe. With hindsight we know what would have been their fate if they had still been in Europe in the 1930s and 1940s, as was the fate of some of my German Seligmann relatives who did not leave Europe in time.

Once again, I feel grateful for the risks that my ancestors all took and for their courage and hard work, which made it possible for me to be here today, remembering them all.

My great-great-grandfather Bernard Seligman, born in Gau-Algesheim, a pioneering leader in Santa Fe, and father of a US governor

[1] Adolph did have children, and I’ve traced all of his descendants, but out of privacy concerns have not written about them since many of his grandchildren are still living, and I have not been in touch with them.

![Cover of "Mrs. Doubtfire [Blu-ray]" Cover of "Mrs. Doubtfire [Blu-ray]"](https://i0.wp.com/ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51SgKMWH4QL._SL350_.jpg)