The other day I wrote about the steps I took to narrow down the thirteen possible Abraham Rosenzweigs in the 1915 NYS census to the one who I am reasonably certain was the Abraham who was the son of Gustave and Gussie Rosenzweig and thus my grandfather’s first cousin. Over the last two days I have been engaged in the same process to determine which of the many Joseph Rosenzweigs I found in the US and NYS census reports was the younger brother of Abraham and also Gustave’s son. I am once again reasonably certain that I have found the right Joseph, but I want to record the process I used to get there, both for my own record-keeping and to invite others to question my reasoning and my conclusions.

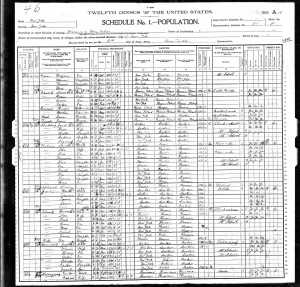

In many ways the search for the right Joseph was easier than the search for Abraham. For one thing, there were far fewer Joseph Rosenzweigs than there were Abraham Rosenzweigs. For another, Joseph was born in 1898 and thus was almost ten years younger than Abraham. That meant that I had five census reports in which Joseph was living with his parents and siblings: 1900, when he was two years old, 1905 (seven years old), 1910 (twelve years old), 1915 (seventeen years old) and 1920 (22 years old). I also found what is definitely Joseph’s draft registration and World War I service record; I know these are for the same Joseph because his address on these two forms, 1882 Bergen Street in Brooklyn, is the same address where the family was living in 1920 according to the 1920 US census.

From these documents I learned a fair amount about Joseph’s early adult life. In 1915 he was employed as a driver’s helper, according to the 1915 census.

Rosenzweigs 1915

In 1917 when he registered for the draft he was working for the BRT, or the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company, which eventually merged into the BMT or Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit Company. It is difficult to decipher the handwriting, but it looks like he was a guard for the BRT, perhaps the same as being a driver’s helper as he had reported in 1915.

Joseph Rosenzweig draft registration World War I

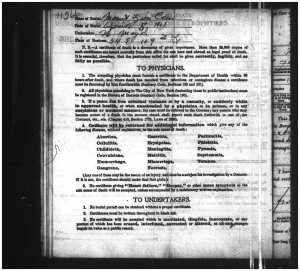

His draft registration also indicated that Joseph was the sole supporter of his mother at this time. By this time Gustave and Gussie had separated or divorced, and on the 1915 census two years before Gussie had been living not only with Joseph, but also with Abraham and Jacob, both already in the US Navy, and Lizzie and Rachel, both still in school and young teenagers. Apparently by 1917, only Joseph was providing support for his mother and presumably his two younger sisters. According to the 1918 abstract of Joseph’s military service during World War I, he served as a Seaman, Second Class, in the US Navy at the Brooklyn Navy Yard from February 8, 1918 until November 11, 1918, Armistice Day, the end of World War I.

Joseph Rosenzweig military service

After the war, according to the 1920 US census, Joseph was still living with his mother and Jacob (Jack), Lizzie and Rachel (Ray) at 1882 Bergen Street and working as an operator in a millinery shop; in other words he was a hat maker. It is this occupation that became critical to my analysis as I moved past the 1920 census to the 1925 NYS census and the 1930 and 1940 US census reports.

There are only two Joseph Rosenzweigs listed on the 1925 NYS census born in New York around 1898. One was living with his parents, whose names were Aaron and Rose, so clearly not our Joseph. The other Joseph was married to a woman named Sadie and had a four year old daughter named Irene. They were living at 308 East 98th Street in Brooklyn, and most importantly, Joseph’s occupation is listed as a hatter. His wife Sadie had been in the United States for 12 years and was born in Russia. Although I have yet to find a marriage record for Joseph and Sadie, it appeared that they must have gotten married in 1920 since they already had a four year old child by 1925. I will continue to search for their marriage certificate as it will provide more definite evidence that the Joseph who married Sadie was the son of Gustave and Gussie Rosenzweig.

Rosenzweigs 1920 census

Joseph and Sadie 1925

Although I would like additional evidence to link this Joseph to Gustave, I am reasonably certain that it must be the right person. The age and birthplace are correct, the occupation is the same as the occupation held by Joseph when he was still living at home with his mother, and there was only one other Joseph Rosenzweig listed in this age range in the 1925 NYS census.

Thus, I moved on to the 1930 census to see if any other Joseph Rosenzweigs were included there who could match the right criteria. On the 1930 census I found two Joseph Rosenzweigs. The first Joseph was born in 1898, but he was living with a brother named David, and Gustave and Gussie did not have a son named David who survived until 1930. The second Joseph was the Joseph who married Sadie. The census reported that he was born in 1897 and had been married to Sadie for ten years, making 1920 again the likely year of their marriage. Sadie’s sister Tilda Kablanski was living with them, and they now had two daughters, Irene (nine years old) and Mildred (four years old). They were still living on East 98th Street in Brooklyn, and Joseph was still employed as a hat maker. There was also a John Rosenzweig who had Romanian parents, which looked promising, and he was living on Albany Avenue in Brooklyn, married to Ethel Bloom. He was working as a postal clerk. Although he was born in 1890 and thus older than Gustave’s son and had the wrong name, I held him aside as a possibility.

The only information in the 1930 census for the Joseph that married Sadie that conflicts with what I know about Joseph, Gustave’s son, is that it reports that his parents were born in Russia, not Romania. I would be more troubled by this if I had not already seen so many errors on census reports: my grandmother’s name listed as Maurica when it was Gussie, my great-grandmother’s name given as Pauline when it was Bessie or Pessel, ages that are inaccurate, relationships described incorrectly, and so on. I had to remind myself not to use this inconsistency to dismiss Joseph and Sadie; genealogists often are reminded that census takers took information often from neighbors or children or anyone who was around when the occupant was not home. So given that there were only two Joseph Rosenzweigs of the right age born in NYC listed on the 1930 census, I decided that it was still more likely that the Joseph who married Sadie was Gustave’s son than the John who was almost ten years older and working as a postal clerk or the Joseph who was living with a brother named David.

Joseph and Sadie 1930 census

So I moved ahead to the 1940 census to see if I could find anything that would help to nail down the identity of the correct Joseph. There were four Josephs (plus the John who married Ethel; since his name was listed as John again, I decided that this was not a census taker’s mistake and eliminated him from my pile.) Once again, there was Joseph who married Sadie, living with their two daughters Irene and Mildred on Rockaway Parkway in Brooklyn. Joseph’s birth year was given as 1899 this time, and his occupation was still in hat-making. There was a second Joseph married to a Sadye, living in Manhattan, but he was older (born in 1894). There was a third Joseph married to a Jenny, also living in Manhattan, who was a salesman of knit goods, but he was also older, born in 1893. And finally there was a Joseph born in 1897, married to Sarah and living in the Bronx. He was a clerk in a rubber factory. Of the four Josephs, it still seemed to me that the one who was most likely Gustave’s son was the Joseph who married Sadie: he lived in Brooklyn, where our Joseph grew up; he was a hatter, which our Joseph had been in 1920; and he was the correct age, unlike two of the other three.

Joseph and Sadie 1940

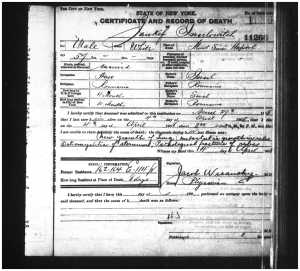

Obviously I cannot be 100% sure unless and until I can find a marriage certificate for Joseph and Sadie which reveals his parents’ names or unless and until I can find a descendant of Joseph and Sadie who may know whether their great-grandfather was named Gustave and whether their great-grandmother was named Gussie. I have sent messages to a few of those descendants, and I am hoping that one of them will be able to help. In the meantime I will continue to search for more evidence linking Joseph to my great-great uncle Gustave Rosenzweig, in particular the marriage certificate or the death certificate for the Joseph who married Sadie.