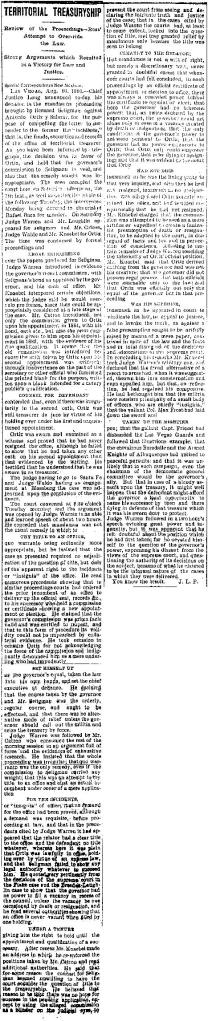

Did my cousin Morton Tinslar Seligman leak classified information to a reporter during World War II?

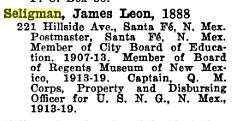

In my last post, I summarized the background to the story of Chicago Tribune reporter Stanley Johnston and his article about the Battle of Midway that revealed that the US Navy had had advance knowledge of the names and locations of various Japanese ships, helping the US Navy to secure victory in that battle. One of the key issues in that story was the question of how Johnston had obtained that information and whether he had obtained it from my cousin, Morton T. Seligman, from a secret dispatch from Admiral Nimitz. Michael Sweeney and Patrick Washburn’s excellent monograph on this topic, “ ‘Aint Justice Wonderful’ The Chicago Tribune’s Battle of Midway Story and the Government’s Attempt at an Espionage Indictment in 1942,” Journalism & Communication Monographs (2014), provides a thorough and carefully researched analysis of this matter.

As I wrote last time, the first government document mentioned in the Sweeney and Washburn article that names my cousin Morton T. Seligman as a possible source of Johnston’s access to classified information was a July 14, 1942 memorandum to the Attorney General and the Secretary of the Navy by William D. Mitchell, the chief prosecutor for the government’s case against the Tribune and its employees. Mitchell’s memorandum claimed that two unnamed officers had seen Commander Morton Seligman writing down a list of the Japanese ships located in the area near Midway. The Mitchell memorandum then noted that Seligman had stated that he did not remember making such a list, but that he might have done so. Sweeney and Washburn, p. 48.

In their research of this matter, Professors Sweeney and Washburn found that Seligman was also mentioned in files from the Tribune’s own internal investigation, files Sweeney and Washburn obtained from the Tribune and its attorneys, Kirkland and Ellis. According to Sweeney and Washburn, “only one officer is repeatedly mentioned in its internal investigation documents as being linked to Johnston—Commander Morton Seligman….Aboard the Barnett, the two of them had bunks that opened onto a common room and the Barnett’s mess set up coffee urns there that made it a popular place for men to gather.” Ibid. at 53.

According to Sweeney and Washburn, “[e]xtensive notes in the legal archive [of the Tribune] make it clear that Seligman shared sensitive information with Johnston aboard the Barnett, but memory problems cause by battle injuries on the Lexington may have prevented him from remembering the details. The memoranda underscore Johnston’s desire to avoid harming the career of any naval officer and they make it clear that he specifically tried to cover for Seligman.” Ibid., at pp. 53-54.

The Tribune/Kirkland Ellis files contained information indicating that Seligman had called the Tribune at least three times between July 17 and August 11, including twice in the days shortly after his meeting with Mitchell. The memoranda describing these phone calls, cited as “Dear Howard, Memorandum” and “Maloney-Seligman Phone Conversation” in the Kirkland and Ellis files, are probably the most damning evidence against Seligman in the Sweeney and Washburn article, albeit quite circumstantial and not originating with Seligman.

In the memoranda describing these phone calls, Seligman is depicted as anxious about the investigation, having been questioned by the Navy and then by the FBI several times in June while he was in the hospital recuperating from his injuries. He called the Tribune to speak with Johnston, and according to these memoranda, was assured by both a Tribune editor and by Johnston that his name had not been revealed to any of the authorities and that they would protect him. According to the memoranda, Seligman told the Tribune that he had told the FBI that he could not remember the Nimitz dispatch or any of the other details they were investigating as a result of his injuries and their effect on his memory. Ibid. at 55. The impression left is that Seligman had revealed something to Johnston or that he feared he had, but could not remember the details.

A final memorandum from the Kirkland and Ellis files dated August 11 that has no named author or recipient and that does not even name Seligman specifically but refers to “S,” a person who appears to be Seligman, also refers to Seligman’s memory problems and his statement that he neither remembered seeing the Nimitz dispatch nor discussing the planned Japanese attack on Midway. Sweeney and Washburn at pp.55-56.

When the case went to the grand jury in August, 1942, Seligman was one of eight naval officers who testified, but I cannot find anything that describes his testimony or whether he was questioned about the Nimitz dispatch or about providing Johnston with any other information. On August 19, 1942, the grand jury concluded that there was not enough evidence to indict the Tribune or its employees, and the case was closed. Ibid., pp. 64-69.

Over 30 years later, a naval officer named Robert E. Dixon, who had been a lieutenant commander aboard the Lexington during the Battle of the Coral Sea and then had been aboard the Barnett after the battle, apparently confided to a newspaper editor named Robert Mason that Seligman had arranged to have decoded copies of Japanese radio transmissions delivered and that Seligman had regularly shown these messages to Johnston. Dixon also told Mason that he had seen Johnston taking extensive notes on these decoded messages. Dixon claimed he did not then immediately report this because Seligman was his superior officer. He claimed, however, that he did disclose all of this to the FBI once Johnston’s Midway story appeared in print. Ibid., pp. 71-72.

This conversation, revealed by Mason in a letter to the editor in 1982 to a naval publication called Proceedings, is not corroborated by any other document in the FBI files or elsewhere uncovered by Sweeney and Washburn and thus remains a hearsay statement by Mason in 1982 about what he claims he was told by Dixon in 1975 about what Dixon claims he saw Johnston and Seligman doing aboard the Barnett in 1942. It may in fact be true, but it is hardly very persuasive evidence at this point. Sweeney and Washburn themselves pose the question in their conclusion: “Did the FBI and Navy believe Dixon or did they believe Seligman? Did they know what Seligman had done or merely suspect it?” Ibid., p. 73. We will probably never know the answer to either question.

There thus remain even now numerous questions about how Johnston got the information and whether Seligman revealed it to him deliberately. Since Seligman clearly was suffering from memory impairment in June and July of 1942, one has to assume that he was also suffering from some impairment in May while aboard the Barnett. If he did reveal the information, it might have been due to carelessness resulting from his medical condition. Even if he revealed it deliberately, it might have been due to some confusion caused by the shock and the injuries he had just suffered. Johnston, who was apparently known even by the Tribune to have been investigated by several governments in Europe for some questionable behavior as a journalist there before he came to the US, might have taken advantage of Seligman’s trust and his impairments to get this information from him. Ibid., at pp.18-21.

Another possibility is that Seligman revealed the information to Johnston off the record, assured that Johnston would not reveal it. One of the quotes from a conversation that Seligman had with Maxwell, a Tribune editor, is consistent with this theory. According to one of the memoranda from the Kirkland and Ellis files, Maxwell stated that Seligman had said to him, “I told [Stanley Johnston] he’d get me in trouble if he used anything we talked about.” Sweeney and Washburn, p. 55. Thus, perhaps Seligman had confided in Johnston, but with the express agreement that it was all off the record and not to be disclosed publicly. Johnston’s disclosure might have been in bad faith or he might have assumed that the Navy censors would block any classified information; it’s not clear whether Johnston knew that the article was not going to be submitted to the Navy for clearance before publication.

Since all the principal actors in the story are no longer alive, all we can do is speculate about the actual events. I certainly do not know what happened, and I admit to some bias in favor of my long-lost cousin. But everything else in his record reflects integrity and honor. He was a man who had already served in the Navy for over twenty years. He had risked his own life a number of times in the course of that service. Why would he ever have done anything deliberately that could be seen as a betrayal of the Navy, an institution to which he had devoted his life, and of the United States during wartime? It makes no sense to me.

From Pinfeather, US Navy Cruise Book (1943) for US Naval Air Station Bunker Indiana, p. 3 , at http://www.fold3.com/image/303178517/

After his hospital stay, Morton Seligman continued his naval service. He was assigned to the Naval Air Station in Peru, Indiana, where he was welcomed as a war hero. Nothing in the press coverage suggests that there was any public knowledge of the accusations made against him. (“Captain Seligman Will Command U.S. Navy Base,” The Kokomo Tribune (September 19, 1942), p. 1; “Lexington Officer to Command Air Post,” Washington Evening Star (September 26, 1942), p.13.)

His service there was marked by further heroic efforts. In May, 1943, there had been a major flood in Kokomo, Indiana, and Commander Seligman was commended for his help in rescuing citizens from th flood waters. The Kokomo mayor praised his leadership, saying, “The commander and his boys, without sleep or rest, braved the dark and cold throughout many long hours until the job was done.” (“Flood Rescue Brings Praise for Coronadan,” San Diego Union (June 24, 1943), p. 1, Section B)

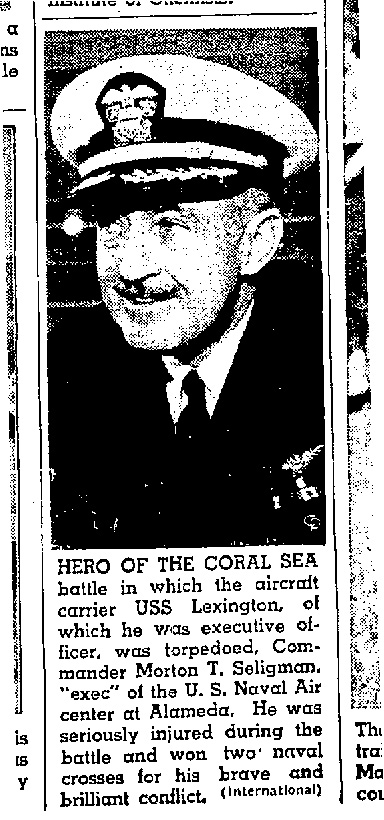

Not long after the flood, Seligman must have returned to San Diego where he was assigned to the post of executive officer of the Alameda Naval Air Station in Long Beach, California. (“Flood Rescue Brings Praise for Coronadan,” San Diego Union (June 24, 1943), p. 1, Section B; photograph, Long Beach Independent, August 31, 1943)

As of November 1, 1944, he was retired from the Navy and was granted a retirement promotion to Captain. Morton lived the rest of his life in the San Diego area with his wife Adela. Morton Tinslar Seligman died from a stroke on July 9, 1967; he was 72 years old. He was survived by his wife and his mother; he had no children.

When I look back at Morton’s life, I feel a deep sense of sadness. He was a man who dedicated his life to service and faced incredible dangers; he lost his sister at a young age, he lived far from his family from the time he was 18 years old, and his first marriage ended in divorce. The Navy must have been the most important part of his life as an adult. Some might say he got away with leaking classified information; I would say he got away with nothing. He suffered both physically and professionally after the Battle of the Coral Sea. The premature end to his military career at age 49 must have been very painful for him. Since there is no evidence of any malicious intent on his part, I believe that he paid a big price for acts that were perhaps caused by injuries he suffered in the line of duty or by the betrayal or carelessness of a reporter he thought he could trust. Whatever the truth, he deserved better after his many years of faithful service.