As I wrote yesterday, I was excited in reading the case file of Jankel Srulovici to see that the principal witness who came forward to vouch for him at the hearing to determine his admission into the US was a brother-in-law named Gustave Rosenzweig. Gustave is the fourth child of my great-grandparents David Rosenzweig and Esther Gelberman whom I have been able to locate. He was my great-grandmother Ghitla’s older brother and also Tillie and Zusi’s brother. I had already noted his name on Bertha Strolowitz’s marriage certificate in 1915, but now I have some verification that he was in fact a member of the same family. Not simply because he testified for Jankel and helped post the bond for his admission, but because he described Jankel and Tillie in his testimony as his brother-in-law and sister.

I have now done research to learn more about this man, my great-great uncle, who had $6000 in assets in 1908 and a painting supply business in Brooklyn and who had already impressed me with his character for helping out his family. From various records, I have learned that Gustave was born in Romania in September, 1861. He married his first wife, Gussie, in 1882, according to the 1900 census.

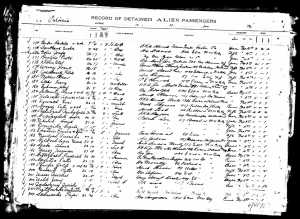

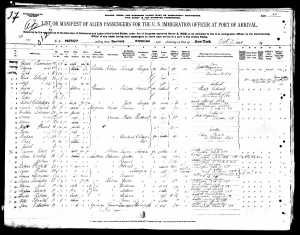

It is not at all clear exactly when Gustave and Gussie arrived in NYC, and I have not yet found a ship manifest for either of them. On his naturalization papers in January of 1892, Gustave wrote that he had arrived on April 12, 1887.

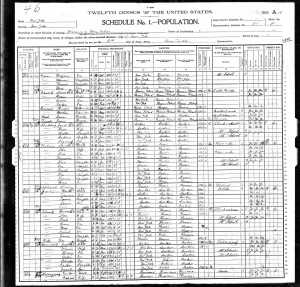

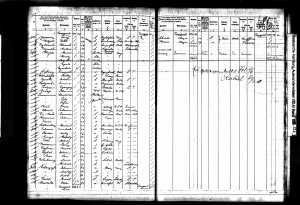

Some of the census reports indicate that Gussie and Gustave emigrated in 1881, others say 1888. According to the 1900 census, their first child Lilly was born in Romania in 1884, and if Lilly was born in Romania, the later date seems to be more accurate. On the other hand, the 1905 and 1910 census reports say that Lilly was born in the United States, and, according to the 1905 census, that Gussie and Gustave had been in the US for 22 years, i.e., since 1883. At any rate, Gustave and Gussie were certainly in the United States by 1888, and thus he was the earliest of the Rosenzweig children to come to America, at least a few years before Zusi, 13 years before his nephew Isidor Strolowitz, 15 years before my grandfather Isadore Goldschlager, and almost 20 years before Tillie, over 20 years before Ghitla.

The earliest record I have of Gustave in NYC is an 1892 New York City directory listing him as a painter, living on Eldridge Street in the Lower East Side. His naturalization papers also indicated that he was a painter, as was Jankel Srulovici and his two sons Isidor and David. It makes me wonder whether Jankel and Gustave had been in business together as painters back in Iasi. Jankel would have been about ten years older, so perhaps he trained Gustave and brought him into his business. Gustave might have felt some sense of gratitude to him as well as brotherly love for his sister Tillie, motivating him even more so to help bring Jankel into the country.

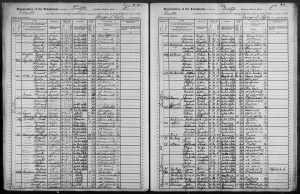

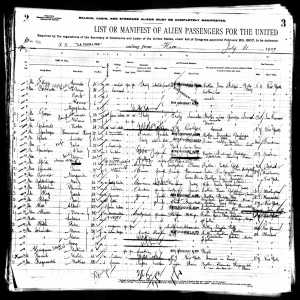

Gussie and Gustave moved several times after 1892—uptown on East 74th Street in 1894, downtown to E. 6th Street in 1900, and to Brooklyn by 1905, where they first lived in Fulton Street and then on Franklin Avenue, where they were living in 1908 at the time of Jankel’s hearing. Throughout this period of time, Gustav was a painter, eventually owning his own paint supply business, and he and Gussie were having many children: after Lilly came Sarah (1888), Abraham (1890), Rebecca (1894), Jacob (1895), Harry (1897), Joseph (1898), Lizzie (1900) and Rachel (1903). Apparently there were five others who died, as the 1900 census reports that Gussie had had thirteen children, eight of whom were then living.

It’s mind-boggling on many levels. First, how did the support and feed all those children and where did they fit them? And secondly, how did they endure the deaths of five children? I’ve seen this many times. In fact, on the 1900 census for Bessie Brotman, my great-grandmother, it reports that she had had nine children, only four of whom where then living. I cannot imagine how these mothers coped with losing these babies. Did it make them less able to bond with each newborn, fearing they would not survive, or did it make them cherish each new child even more, knowing how fragile life was and how difficult it was for a child to survive?

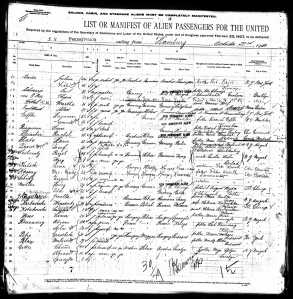

In addition, it appears that one of the children who survived infancy, Harry, died as a teenager in 1913. Perhaps all this did take its toll on the family. By 1915 it appears that Gustave and Gussie had separated or divorced. Gussie is living alone with the children in 1915; I cannot find Gustav at all on the 1915 census. The census reports for 1920 also had me somewhat confused. I found Gustave on two reports, one in Brooklyn on Bergen Street, living with the four youngest children, and another in Manhattan on East 110th Street, living as a boarder with another family. In the Brooklyn census report, Gustave is listed as having no profession; on the Manhattan one it says he was a painter. And I could not find Gussie anywhere, though the Brooklyn census said that Gustave was divorced. What I finally concluded was that the Gustave in Brooklyn was really Gussie, despite the fact that it said Gustave and listed him as male. My guess is that, as was often the case, the census taker was given or heard confusing information and misinterpreted it. It makes more sense, given the times, that the children would be with their mother and that a woman would not be employed outside the home. The Manhattan Gustave, the painter, is obviously the actual Gustave Rosenzweig.

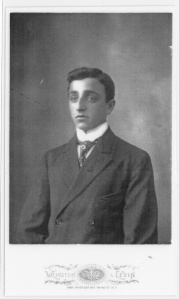

By 1925 Gustave was remarried to a woman named Selma Nadler. I was able to find a family tree containing Gustave and Selma which included this photograph, apparently of Selma and Gustave. Selma had also been previously married and had ten children of her own.

Between them, Selma and Gustave had nineteen living children in 1925. Imagine what that family reunion would look like. The last record I have for Gustave is the 1930 census. I have not found him yet on the 1940 census. I have found two death records for men named Gustave Rosenzweig, one in 1942, the other in 1944. I have ordered them both to determine whether either one is our Gustave.

Meanwhile, Gussie continued to live with one or more of her children in 1925, 1930 and 1940. I do not yet have a death record for her either. I have been able to trace the nine children with varying degrees of success. Lilly appears to have had a child out of wedlock in 1902 named William who was living with Gustave and Gussie for some time in 1905, but who was placed in an orphanage (father listed as Frank with no surname and deceased) for a short time in 1906.  Then Lilly reappears on the 1910 census living with her parents and without William. I’ve not yet learned what happened to either Lilly or William.

Then Lilly reappears on the 1910 census living with her parents and without William. I’ve not yet learned what happened to either Lilly or William.

Similarly, the other four daughters Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Lizzie, all became untraceable after they left home since I have no idea what their married names were. As for the sons, Abraham married and had two daughters, who for similar reasons I cannot find after 1940. Jacob/Jack also had two daughters, and Joseph I’ve not yet found past 1920. So at the moment I have not located any current descendants, but I will continue to look to see if I can somehow find out the married names of some of Gustave’s granddaughters. The NYC marriage index only contains records up to 1937, and these grandchildren would not yet have been married by then; thus, I have no readily available public source to find their married names. It may take a trip to NYC to see if those records are available in person. Or perhaps I can find a wedding announcement.

UPDATE: Much of the information in the preceding paragraph has been updated here, here, here, here, here, here, and other posts on the blog on Joseph, Jack, Rebecca and Sarah.

So that is the story of Gustave Rosenzweig as I know it to date: a Romanian born painter who married twice, had nine children, real estate and a painting business, and who came to the rescue of his sister and her family. It would be wonderful to know what happened once they all settled in America. Gustave obviously stayed in touch with Tillie and her children, as he was present at Bertha’s wedding. Did he help out Zusi, his little sister, when her husband died? I had hoped to find her living with him on one of those census reports, but did not. Did he help out my grandfather when he arrived as a 16 year old boy in NYC in 1904? Did he help out my great-grandmother when she arrived in 1910, a widow without any means of support aside from her children? I certainly wish there was some way of knowing the answers to these questions. From his conduct at the hearing for Jankel in 1908, I’d like to think that Gustave was there for them all, but we will never know.