As we saw, Malchen Rothschild and Daniel Rosenblatt’s daughters all were killed in the Holocaust. Their son Julius had died as a young man, leaving behind a young widow Julie Rosenblatt and their infant son Fredi. Julie and Fredi escaped to Uruguay, and thanks to Fredi’s son Julio, I’ve been able to learn and share much of their story.

Malchen and Daniel’s other two sons Felix and Siegmund escaped to Argentina, not Uruguay,1 and thanks to the magic of the internet, I am now in touch with Felix’s granddaughter in Argentina, Carmen. I found a photograph of the gravestone of Felix’s son Ludwig Rosenblatt (see below) on JewishGen and posted it on Tracing the Tribe, asking for a translation of the Hebrew inscription. A woman in the TTT group tagged Carmen when she saw my post, and Carmen, Ludwig Rosenblatt’s daughter, responded. Although Carmen doesn’t speak English and I don’t speak Spanish, we’ve managed to communicate, thanks to Google Translate and DeepL.

Carmen shared with me a lecture2 she delivered in 2018 to the Latin American Rabbinical Seminary about the community where her family has lived since 1936 when they immigrated from Germany to Argentina. It is in Spanish, and I’ve used DeepL to translate it and now will paraphrase and take excerpts from the translation to share the story of Carmen’s family and their community. Carmen also filled in other details through email.

As Carmen explained in her lecture, the German philanthropist Baron Maurice de Hirsch formed the Jewish Colonization Association (“JCA”) in the late 19th century to acquire land and create settlements in Argentina for Jews escaping persecution in Russia and Eastern Europe. When Hitler came to power in the 1930s, it became apparent that there was a need for more land and more places for German Jews to escape, so the JCA acquired additional land to create a new settlement called Colonia Avigdor, which is over 300 miles from Buenos Aires.

Thanks to the efforts of the JCA, Jewish families like Carmen’s were able to escape Nazi Germany. I asked Carmen what convinced her grandparents to leave Germany. She wrote that one night her grandfather’s car was confiscated by the Nazis in Zimmersrode, and when it was returned to him the next day, an official in the town told him: “Felix, this is getting very ugly for you Jews, take your family and leave Germany.” Felix replied, “How??? I have to sell my house, my things.” The official replied, “Leave everything, don’t sell anything… nobody is going to pay a Jew.” Felix contacted the JCA and asked for help to leave Germany and move to Argentina.

Carmen’s grandparents Felix and Minna (Goldwein) Rosenblatt and their sons were one of the ten families that first settled in Colonia Avigdor. They arrived in Buenos Aires, Argentina, with their sons Ludwig, then 17, and Siegfried, 20, and their daughter-in-law, Siegfried’s wife Jenny Feilmann, on January 25, 1936. As Carmen explained to me and in her lecture, because the JCA required a family to have five adults to qualify for the settlement program, Siegfried, although only twenty years old, had married Jenny at such a young age in order for the family to qualify.

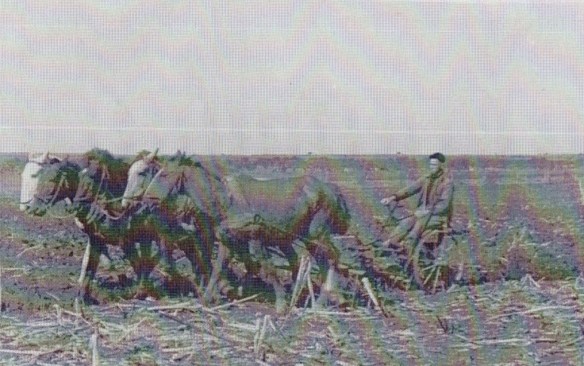

After a few days in Buenos Aires, Felix, Minna, and their family traveled by train from Buenos Aires to Bovril, the closest train station to Avigdor. From there they traveled the last fifteen miles of the over 300 mile journey “by horse-drawn carts through trees and bushes in the woods along winding paths” to get to their new home. Carmen wrote that they were “full of hope that they would adapt to such a hard life and happy to set foot on land that promised above all FREEDOM and work to build a good future.”

Carmen’s description of their early lives cannot be paraphrased adequately; here is how DeepL translated her words:

Each of the settlers was allocated 75 hectares of land and a poorly constructed house made of mud-covered bricks with a dirt floor, two rooms, one kitchen, one veranda, and a bathroom at the back, about 10-15 meters away from the house. In each house, they found a bag of hard “cookies” (country bread), several days old… as well as some work tools, a few cows, some horses, some chickens… The next day, they got to work, first clearing the yards of wild trees, then the fields so they could plant them, building fences to divide them. It was very hard work, but as I said, they were happy because they had hope for progress. The women devoted themselves more to the tasks in the yard, tending to the chickens and other poultry, milking the cows for the milk they consumed, in addition to their household chores. They had to knead the bread in wood-fired ovens, whose mouths opened into the kitchen…

They say that at first, these women did these tasks crying practically all day (and at night too) because of the precarious conditions around them… there was no electricity, the lamps were kerosene… there were no refrigerators, no appliances whatsoever. And it should be emphasized that they came from an advanced civilization in Germany… Some, those who came from small towns, adapted more easily, but those who came from cities such as Berlin, Munich, Frankfurt, etc., of which there were many… found it extremely difficult, or simply could not get used to it…

The community grew as more and more refugees came from Germany; eventually there were about 120 families. The settlers engaged in many forms of agricultural work: dairy, livestock, farming, gardening, and beekeeping. They established a cooperative to market their products. A school was established by the JCA, and there was a post office, a synagogue, a kosher butcher, and a Hebrew teacher. There was even a small hospital to provide health care to the settlers and a social center for dances, theaters, and orchestral performances. Land was also set aside for a cemetery.

But conditions remained fairly primitive for a long time. It wasn’t until 1971 that there was electricity in the colony, and there were only dirt roads until 1987. Despite all these challenges, Felix and Minna and their children remained at Colonia Avigdor, working hard to achieve their dreams.

Their younger son Ludwig Rosenblatt married Ruth Plaut, another refugee from Germany, in 1944. They had two children, Carmen and her sister Alicia. Ludwig’s older brother Siegfried and his wife Jenny also had two daughters, Miriam and Lenore.

Felix Rosenblatt died on February 4, 1955, and is buried at the Centro Unión Israelita de Colonia Avigdor cemetery in Colonia Avigdor, Argentina, as is his wife Minna Goldwein Rosenblatt, who died on February 16, 1969. Here is a photograph of their gravestones.

Felix and Minna Rosenblatt headstones from JOWBR database, found at https://data.jewishgen.org/imagedata/jowbr/ARG-06046/WA0125.JPG

Their son and Carmen’s father Ludwig Rosenblatt died on October 10, 1977, and is buried at the same cemetery as his parents. He was only 57 when he died. As translated by the kind people at Tracing the Tribe, the Hebrew reads: “Here [lies] buried / Leib son of Uri / a reputable man / a faithful protector of / his family / an example for his descendants / [we] remember him with love / may his soul be bound in the bond of [eternal] life.” The footstone engraving in Spanish mentions his wife, children, and grandchildren; it was placed there on the occasion of what would have been his 70th birthday on November 15, 1989.

Ludwig Rosenblatt headstone at JOWBR database, found at https://data.jewishgen.org/imagedata/jowbr/ARG-06046/WA0143.JPG

As for Siegfried Rosenblatt, Felix’s other son, he died on October 23, 2004, and is buried at Cementerio Israelita De San Vicente Cordoba, in Cordoba, Argentina; he was predeceased by his wife Jenny Feilmann who died on May 23, 1978, and is buried in the same cemetery.3 Their daughter Lenore, who was born on November 2, 1940, died on April 27, 2001.4

Carmen still lives in Colonia Avigdor with her husband Abraham Isaac Kogan, whom she married almost 58 years ago. They had two sons, one of whom passed away; the other still lives in Argentina, but not in Colonia Avigdor. Today there are only about twelve Jewish families left in Colonia Avigdor because many people left long ago to live in the cities. Carmen wrote, “These days, basic services such as electricity, water, roads, television, communications, etc. are practically comparable to those in cities… the precariousness has been overcome… but let’s not forget that since the founding of Avigdor in 1936, 82 years have passed… and the vast majority have left…”

Carmen generously shared with me some photographs of her extended family. This photograph was taken at her wedding in 1967.

Photograph taken at Carmen Rosenblatt’s wedding to Abraham Kogan in 1967, courtesy of Carmen Rosenblatt. Standing from left to right: Ruth Plaut, Carmen’s mother; Ludwig Rosenblatt, Carmen’s father; Abraham Isaac Kogan; Carmen Alexander; Jenny Feilmann, wife of Siegfred Rosenblatt; Siegfried Rosenblatt, Carmen’s uncle Seated: Family friend,\; Minna Goldwein, Carmen’s grandmother; Else Schwab, wife of Sigmund Rosenblatt; Sigmund Rosenblatt, Carmen’s great-uncle.

This more recent photograph was taken in 1981 on the occasion of Carmen’s son’s bar mitzvah. I think it illustrates how Jewish traditions are similar all over the world. This photograph could have been taken at any bar mitzvah in the US in 1981, and it would have looked very much the same.

Carmen’s story has given me a new perspective on the lives of those who escaped from Nazi Germany. It’s hard to imagine how they adapted to such a hard life—a precarious one, to use Carmen’s word. They were coming from a place where their ancestors had lived for centuries to a primitive place, far from any city, where people spoke a language they didn’t know, and they had to live according to the rules and subject to the authority of the JCA—and yet they were filled with hope and grateful for the chance to survive and live freely.

All this reminds me to be grateful for what I have and to empathize with all those around the world who are forced to abandon their homes in search of a safer and better life.

- Although they came from different villages in Germany and ended up in different countries in South America, the Rosenblatts in Uruguay and the Rosenblatts in Argentina have stayed in touch and even visited each other over the years. Julie Rosenblatt was a first cousin to Felix and Siegmund as well as their sister-in-law. ↩

- Carmen Rosenblatt, unpublished lecture, “Immigracion de Judio Perseguidos en Alemania, Colonizados en Los Campos de Colonio Avigdor (Entre Rios),” (September 2018). ↩

- See burial records at the JOWBR database at JewishGen, found at https://www.jewishgen.org/databases/cemetery/jowbr.php?rec=J_ARGENTIN_0036804 and at https://www.jewishgen.org/databases/cemetery/jowbr.php?rec=J_ARGENTIN_0036805 ↩

- See burial records at the JOWBR database at JewishGen, found at https://www.jewishgen.org/databases/cemetery/jowbr.php?rec=J_ARGENTIN_0071081 ↩