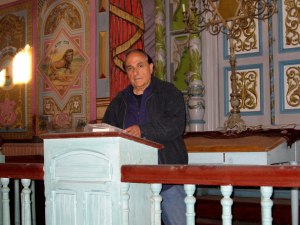

Arthur Lewis Wilde Cohen, Sr.

When I first started researching my Cohen relatives about a year and a half ago, I was very fortunate to find one branch on that tree already recorded on ancestry.com by one of the direct descendants of Reuben Cohen, my great-granduncle. The tree was created by the grandchild of Reuben and Sallie’s son Arthur Lewis Wilde Cohen. I contacted the tree’s owner, and we exchanged a series of emails that established our family connection and that provided me with some wonderful background on Arthur Lewis Wilde’s children and grandchildren as well as some photographs. This newly found third cousin of mine, Jim, was very helpful when it came to his father’s generation, but said he knew very little about the lives of his grandfather Arthur Lewis Wilde Cohen, Sr.,or his great-grandfather Reuben.

I filed away all the information and the photos my new cousin Jim shared with me, and then began to focus on my Brotman relatives, putting the Cohen research to the side for many months. When I returned to the Cohens this spring, I dug up the information I’d gotten from Jim. In researching more deeply into the life of Arthur Lewis Wilde Cohen and his family, I experienced what all family researchers experience—that although family stories can almost always be very helpful in providing clues and richness to family history, you have to take into account that details often get blurry as stories are passed down from one generation to the next and that some facts are lost along the way. It took me some doing to untangle the family stories and find the facts, but with more research and more email conversations with Jim, I think I can now piece together the life of Arthur Lewis Wilde Cohen and his family.

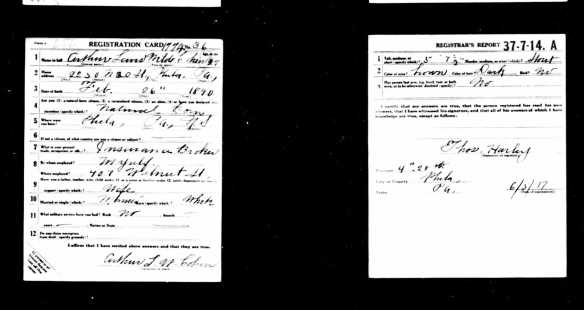

Number eleven out of seventeen, Arthur Lewis Wilde was born on February 26, 1890. In 1910, he was a clerk in a “brokerage.” At first I thought this referred to the pawnbroker business, but since his two brothers Reuben, Jr. and Lewis II, were listed as clerks in a loan office, not a brokerage, I was not sure. Apparently he was an insurance broker, as I found out from his draft registrations.

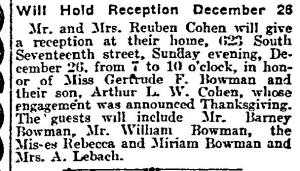

In December 1915, when he was 25, Arthur became engaged to Gertrude Fanny Bowman of Richmond, Virginia, and they were married on March 27, 1916, in Richmond.

(“Will Hold Reception December 26,” Date: Sunday, December 19, 1915 Paper: Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA) Volume: 173 Issue: 172 Section: News Page: 5)

According to his 1917 World War I draft registration, Arthur was self-employed as an insurance broker, and he and his wife Gertrude were living in Philadelphia at 2250 North 20th Street.

Arthur enlisted in the Navy in April, 1918, and was honorably discharged in December, 1920. By 1920, however, Gertrude was back in Richmond, living with her sister and identifying as single and working as a stenographer.

I cannot find Arthur on the 1920 census as he was serving in the military and perhaps overseas, but presumably the marriage with Gertrude was over. Gertrude apparently never remarried and died in 1963 in Richmond.

Emilie WIley Cohen

By 1930 Arthur had married a woman named Emilie Wiley, who had also been previously married. Emilie had married Frank G. Brown in 1905 and had had two daughters with him, Dorothy, born in 1906, and Jean or Jenette, born in 1908. Emilie also was divorced or separated by 1920, and sometime after the 1920 census she married Arthur LW Cohen. They had two children, Arthur, Jr., and Emilie, who were 8 and almost 5, respectively, at the time of the 1930 census.

Living with Arthur and Emilie in 1930 in Philadelphia, in addition to their two own children Arthur, Jr. and Emilie, were Emilie’s mother, aged 81, Emilie’s daughter Jean Harral, and Jean’s son Richard Harral, Jr. Emilie’s older daughter, Dorothy (or Dot, according to my cousin) had married Leroy Lewis in 1928 in Norristown, Pennsylvania, and was living out that way in 1930. She and Leroy had one daughter, and Dot lived in Norristown until her death in 1992.

Jean had also married sometime before 1927 when Richard Harral, Jr. was born. Although she still listed her status as married in 1930, she was apparently no longer living with Richard Harral, Sr., who eventually remarried and lived in Upper Darby, Pennsylvania for the rest of his life with his second wife and their two children.

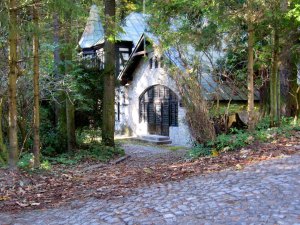

Sometime after 1930, Arthur and Emilie moved permanently to Cape May, New Jersey, where they lived in the house at 208 Ocean Street that had been in Arthur’s family for many years as the summer home of Reuben and Sallie and their children when Arthur was growing up. Although I cannot find Arthur on the 1940 census, according to his World War II draft registration, he was still living at 208 Ocean Street in 1942 and was self-employed, working at the Land Title Building in Philadelphia.

Arthur Sr’s grandson Jim believed that his grandfather had been a jeweler, but I cannot find any evidence of that in the records as it appears that at least up until 1942, Arthur Sr. was still working in the insurance business in Philadelphia. What Jim did share with me was that his grandfather was well-respected and loved by many people. He was a very humble and generous man who never wanted recognition for his generosity.

Arthur, Sr, was also someone who fought off death several times. According to Jim, “He was erroneously pronounced dead four separate times (shades of Simon), all as a result of heart attacks. According to stories told by my father and aunt, on one of the occasions he woke as an orderly was wheeling him to the morgue. When he did, the orderly fainted. The fifth and final pronouncement was also from heart attack he suffered in the family home on Ocean St. This time, it was permanent.”

He died in 1955 at age 65 and was buried at Presbyterian Cemetery in Cold Spring, New Jersey, less than four miles from the family home at 208 Ocean Street.

His widow Emilie applied for a military headstone for Arthur and requested a Christian, not a Hebrew, symbol to be placed on that headstone. Although his mother Sallie may not have been Jewish, as noted earlier, Arthur had been confirmed in Mickve Israel Synagogue in Philadelphia when he was fifteen years old. Then again, his father Reuben had made a donation to the Episcopal Church in Cape May. I asked Jim about the family’s religious affiliation, and he told me that he was not sure whether his grandmother Emilie was born Jewish, but that both of his grandparents practiced Christianity after they were married. Despite this, Jim said that his father, Arthur LW Cohen, Jr., was Jewish and Jim himself is Jewish. As Jim described his parents’ approach, I was amazed by how inclusive his parents were in their approach, letting each of their children find a path that worked for them, each parent maintaining their own chosen path but also sharing in and respecting the other’s chosen path. Apparently his grandparents had done the same.

Jim was able to tell me a great deal about Arthur and Emilie’s children, Arthur, Jr., and his sister Emilie. With his permission, I am quoting directly from his messages to me about his parents:

My father, Arthur, Jr. (“Bud”), was also a jeweler. After he came home from World War II, he opened a repair and retail jewelry store on the first floor of the family home at 208 Ocean St. in Cape May, NJ. It remained open for the next 48 years until his death in 1991.

Arthur Lewis Wilde Cohen, Jr.

He was very active in the Cape May community and loved the city dearly. He was president of the Mall Merchant’s Association for over 20 years, was instrumental in having the entire city declared a National Historic Landmark (it’s one of the few full towns registered as such) for its standing Victorian-era homes and history; and if there was any event – from silly pet parades to building dedications, Memorial Day ceremonies, Easter, Halloween, Christmas parades, and so on, you name it – he was always the Master of Ceremonies. He had a fatal heart attack in the early-morning hours of February 18, 1991.

My mother, Martha, was a music teacher and opera Soprano who attended the Juilliard School of Music. She retired from her opera career almost as soon as it started so that she could marry my father. She became a music teacher and sang at many events and functions. The Goodyear family always contacted her to sing at their family events – mainly weddings and funerals (which always amused me). She died in 2005 following a series of strokes.

He also told me this about his Aunt Emilie:

Aunt Emily Marion Cohen-Brown (who went by “Marion” or, as a nickname I’ve never understood, “Mitchell”), was a first-class florist and lived here in Cape May until her death from cancer in 2003. She had one son, Gary, who lived in Oregon and made unbelievable fudge. I know he had a wife and kids, but we’ve lost contact. He predeceased her, also from cancer. I never met her husband, Harry, who died before I was born. She made the absolute best Navy bean soup you could ever taste, and I wish I had the recipe.

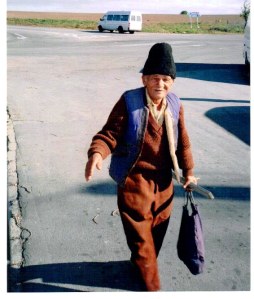

Although not a genetic relative of the Cohens, the story of Arthur Sr.’s stepdaughter Jean Harral and her son Richard is part of the family lore of Arthur Lewis Wilde Cohen and his descendants, so I will share it here. Richard was mentally disabled, and at some point he and his mother Jean moved to New York City together. Richard was working as a messenger for a company in New York, and his favorite pastime was sailing a model sailboat on the pond in Central Park. In November, 1975, he was stabbed to death, apparently by a friend. I could find no record of a trial or further development in the case aside from these few news articles from the New York Times.

In December, 1975, just a month after Richard’s murder, his mother Jean died; accordingly to family lore, she starved herself to death out of grief over the death of her son.

I am deeply indebted to my cousin Jim for sharing his family’s stories with me as well as the photographs posted here. There is nothing more meaningful for me in doing this project than hearing about my long-lost relatives from those who knew them best.