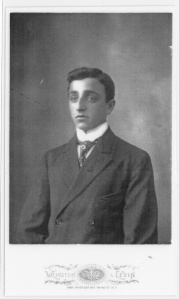

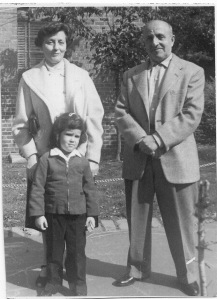

Isadore Goldschlager

“Grandpa walked out of Romania to escape from the Romanian army.” That was the one story I knew about my grandfather’s life before he came to the US as a teenager. I knew a few other snippets about him in general—that he loved music and animals, that he knew multiple languages, that he was a union activist and very left-wing in his political views, that he was a milkman, and that he was a terrible tease and had a great sense of humor. But the story about him walking out of Romania was the one that always intrigued me the most. I would ask my mother questions: Did he go alone? Where did he walk to? How did he get to the United States? But she knew nothing more than that barebones story—that as a teenager, he decided to run away from the army and walked across the country to escape.

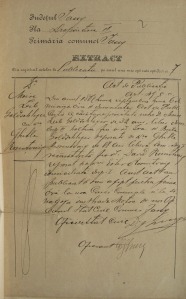

When I first started researching my grandfather’s family, I wanted to know more about this story. Was it just a myth, or was there any factual basis to it? I did some initial research and learned that there was in fact an entire movement of Jews who left Romania by foot beginning in the early 1900s, around the same time my grandfather left (1904). These walkers were known as the Fusgeyers or “foot-goers.” Unfortunately, I could not find many sources of information about this movement. I found only two books devoted in depth to the topic. One is a novel called The Wayfarers by Stuart F. Tower; although written as a novel, it was inspired by the author’s actual search to learn about the Fusgeyers. It tells the story of an American man whose grandfather left Romania by foot. The grandson, now an adult, takes his own teenage son and his elderly father to Romania to learn more about his grandfather’s escape from Romania. The author describes long conversations that the lead character had with a rabbi living in Romania who was familiar with the Fusgeyer movement. Although this book gave me a taste of what the movement was like, I wanted to read something more fact-based and scholarly to understand and know more about the Fusgeyers.[1]

I found that in the second book about the Fusgeyers: Finding Home: In the Footsteps of the Jewish Fusgeyers by Jill Culiner. This book, a work of non-fiction, is fascinating and heart-breaking. After reading Jacob Finkelstein’s “Memoir of a Fusgeyer from Romania to America,” an unpublished Yiddish manuscript written around 1942 and held by the New York-based YIVO Institute, Culiner, not herself a descendant of Romanian Jewss, decided to retrace the routes taken by the Fusgeyers as they walked out of Romania. She actually walked these routes, visiting all the towns and cities along the way, asking current residents what they remembered of the Fusgeyers and of the Jewish communities that existed in those towns before the Holocaust. What she learned about the past and present in Romania is what makes the book both fascinating and heart-breaking, and in a subsequent post, I will write more about that. But first, I want to set the scene by describing what I learned from this book and elsewhere about why the Jews left Romania in the early 1900s.

As reported by Culiner and others[2], Jews had likely been living in the two principalities that became Romania, Walachia and Moldavia, since Roman times. The Jewish population increased significantly in the second half of the 14th century when many Jews from Hungary and Poland immigrated there after being expelled from their home countries. (Wikipedia). Ironically, Romania eventually became one of the most anti-Semitic of the European countries. In 1640, the Church Codes of Walachia and Moldavia declared Jews heretics and banned all relationships between Christians and Jews. (Culiner, p. 15). During the 17th and 18th century, there were repeated “blood libel” accusations against Jews—being accused of killing Christian children for their blood— followed by violence and persecution. (Culiner, p. 15; Wikipedia).

The widespread anti-Semitism really came to a head in the mid-nineteenth century during the movement for Romanian independence and the unification of Walachia and Moldavia into the independent nation of Romania. As the report on Romanian anti-Semitism on file with Yad Vashem reports, after the Crimean War and the defeat of Russia, which had previously controlled Walachia and Moldavia, the European powers (primarily France and Britain) put a great deal of pressure on the leaders of the independence movement in the region to grant Jews full legal status in the new country. Although the leaders had originally argued for such rights during the uprisings against Russia, the external pressure created a great deal of resentment, and in the end the European powers backed off from insisting on full legal rights for the Jewish residents of the newly-united nation of Romania. (Yad Vashem report).

The Yad Vashem report continues: “A real explosion of openly expressed antisemitism occurred as the prospect of achieving national independence became more certain. During discussions of the new Constitution of 1866, Romanian leaders began to portray Jews as a principal obstacle to Romanian independence, prosperity, and culture.” As finally drafted, Article 7 of the new Constitution for Romania provided that “[t]he status of Romanian citizen is acquired, maintained, and forfeited in accordance with rules established through civil legislation. Only foreign individuals who are of the Christian rite may acquire Romanian citizenship.” Culiner described this development, saying that “anti-Semitism had now become part of the national identity.” (Culiner, p. 15)

Despite protests and outcry from western European countries, the new country persisted in its anti-Semitic views and practices. Between 1866 and 1900, a number of laws were enacted restricting the business and other activities of Jewish residents in Romania. Jews could not become officers in the military, customs officials, journalists, craftsmen or clerks. Jews could not vote or obtain licenses to sell alcohol. Jews could not own or cultivate land. Jews could not own or manage pharmacies. They could not work in psychiatric institutions or receive care as free patients in hospitals. Jews could not sell tobacco or soda water or certain baked goods. Fewer than ten percent of Jewish children were allowed to attend public schools, and Jews were prohibited from opening their own schools. Jews were not allowed to work as peddlers, which was sometimes interpreted to include owning shops. Jewish homes were randomly destroyed as “unsanitary.” (Culiner, pp. 16-17)

Culiner wrote: “Eventually, 20,000 Jews found themselves on the streets of Romania and dying of starvation. There were many suicides in Iasi, Bacu, and Roman….In 1899 and 1900, harvests were poor and a severe depression gripped the country. Anti-Semitic decrees were applied with new severity and anti-Jewish speeches were delivered in parliament. Riots took place in several towns, and…a pogrom broke out in Iasi.” (Culiner, pp. 17, 19) (See also Wikipedia and the Yad Vashem report on Anti-Semitism in Romania.)

That pogrom in Iasi was described in the American Jewish Yearbook of 1900: “For several hours there was fighting, merciless blows, pillaging and devastation, all under the paternal eyes of the police authorities and the army, which interfered only to hinder the Jews from defending themselves.”[3]

In 1900, my grandfather was twelve years old. He lived in Iasi. He experienced this horrible violence and hatred. By that time his uncle Gustave and his aunt Zusi had already left for America. Is it any surprise that this young teenager would have wanted to escape from his homeland and seek refuge someplace else?

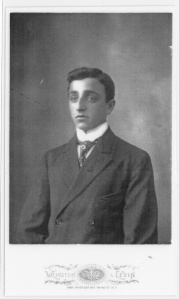

Isadore age 27

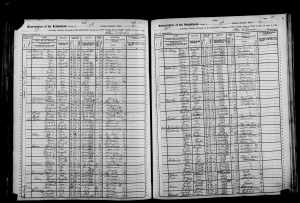

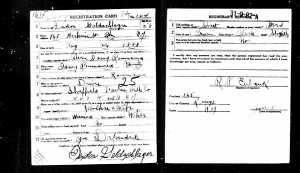

As I will report in a later post, he and thousands of other Jews did leave, many on foot, walking out of Romania to find a better life. My grandfather followed his uncle and his aunt, who had left in the late 1880s, but he left alone, without his parents or siblings. His first cousin Srul Srulovici, who became Isador Adler, had left two years before him in 1902, also alone and without his parents and siblings. My grandfather left in 1904, and by 1910 the rest of his family—his siblings, mother and father and the rest of his Srulovici cousins—had also arrived. I don’t know the details of how any of them got out or whether they were also Fusgeyers, but they all followed their two oldest sons and brothers, both to be called Isadore in the United States.

So my grandfather left Romania on foot, but not only to escape the Romanian army. He escaped a life of poverty, of hatred, of discrimination. He was only sixteen, but he was brave enough, smart enough, and strong enough to get out of a place that held no future for him. He led his family to freedom. Whatever life brought them in America, and it wasn’t easy, it was better than what they had left behind.

[1] Apparently the novel is being turned into a documentary about the Fusgeyer movement. See https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1552736981/the-wayfarers-the-story-of-the-fusgeyers

[2] Wikipedia has a long and detailed article on the history of the Jews in Romania at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Jews_in_Romania. I also consulted other sources, such as a report on Romanian anti-Semitism filed on the Yad Vashem website at http://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/about/events/pdf/report/english/1.1_roots_of_romanian_antisemitism.pdf

[3][3] “Romania since the Berlin Treaty,” The American Jewish Yearbook (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1900), p. 83, as quoted in Culiner, p, 19.