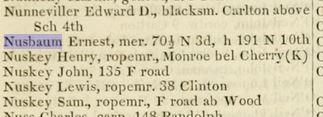

In the early 1870s Moses and Caroline (Dreyfuss) Wiler were living at 905 Franklin Avenue, just a few houses down from Caroline’s sister, Mathilde (Dreyfuss Nusbaum) Pollock and just three blocks away from their third sister, Jeanette (Dreyfuss) Nusbaum and her husband John, my three-times great-grandparents. Ernst Nusbaum and his wife Clarissa were living down the block from his brother John. The area is known as the Poplar neighborhood in North Philadelphia. Plotting all their addresses on the map made me smile. They must have all been so close, not only geographically but emotionally, to live so close to their siblings. Imagine all the first cousins (some double first cousins) growing up within a short walk of each other.

But as I wrote in my last post, things were not quite so idyllic in the 1870s. The Panic of 1873 and the depression that followed had an impact on the family. Like Mathilde and Moses Pollock, Caroline and Moses Wiler also must have felt some of that impact. In 1873 Moses Wiler was listed in the directory without an occupation. His partnership with his brother-in-law Moses Pollock had ended. In 1875 he was still listed without an occupation, and they had moved from Franklin Avenue to 920 North 7th Street, still within two blocks of Caroline’s sisters.

Caroline and Moses Wiler’s son Simon also seems to have been affected by the Long Depression. He had been part of the Simon and Pollock cloak and dry goods partnership of the late 1860s and early 1870s with his father and uncle. After that business ended, Simon had a separate listing in the 1875 directory as a salesman, living at 701 North 6th Street, again in the same neighborhood as his extended family, just a few blocks south. Simon was 32 and not married and presumably was doing well enough to afford his own place. By 1877, however, he had moved back home with his parents at 920 North 7th Street.

In 1879, Moses Wiler was in the dry goods business, and his son Simon was a salesman, both living at 902 North 7th Street, as they were in 1880. According to the 1880 census, Simon was a paper salesman, and Moses, who was 63, was a retired merchant. Perhaps Moses had retired as early as 1873 when his listing no longer included an occupation. Maybe he had done well enough to cope with the economic depression that occurred in 1873.

House on Poplar Street, perhaps like those lived in by the extended Nusbaum-Dreyfuss family in the 1870s https://ssl.cdn-redfin.com/photo/93/bigphoto/440/6336440_0.jpg

By 1880, the three daughters of Caroline and Moses Wiler were no longer living with their parents. Eliza Wiler had married Leman Simon in 1863, and in 1870 they had two children living with them, Joseph, who was five, and Flora, who was three. Sadly, in 1869, they had had a baby who was still born. In 1870 they were living at 718 Coates Street, an address that appears not to exist anymore but was located where Fairmount Avenue is now located between the Delaware River and Old York Avenue. Leman was in business with his brother Samuel, as he was in 1871. That business must have then ended. According to the 1872 directory, Leman was then in the cloak business with his father Sampson Simon, who was living at the same address on Coates Street. In 1874, Leman and Eliza had another child, Nellie, born on November 18 of that year.

By 1876, Leman was listed as a salesman, living at 920 North 7th Street with his in-laws, Moses and Caroline Wiler. Like Simon Wiler, Leman must have been feeling the effects of that Long Depression to have moved in with his in-laws after having his own home. The next time Leman showed up in my search, he and Eliza were living in Pittsburgh, and Leman was working in the liquor business, like his cousin Albert Nusbaum. Although I cannot find Leman on an 1877, 1878, or 1879 directory in any city, Leman and Eliza had another child, Leon, who was born in Pittsburgh on June 13, 1878, so the family must have relocated to Pittsburgh from Philadelphia by then.

Leman and Eliza also had a daughter Minnie, who was apparently born in 1877. I say “apparently” because I cannot find a birth record for her, and there are only two census reports that include her, the 1880 and 1900 census reports. The first says she was 2, meaning she was born either in 1877 or 1878; the latter says she was born in December, 1877. But if she was born in December, 1877, then Eliza could not have given birth to Leon in June, 1878, just six months later. I do have an official record for Leon’s birthdate with Eliza Wiler and Leman Simon named as his parents, so either Minnie was born sometime before September, 1877 or she is not Eliza’s child.

There are no other records I can find to determine Minnie’s precise birthdate; her death certificate also only specified her age, not an exact date of birth, and it also is consistent with a birth year of either 1877 or 1878. Minnie died on August 5, 1904, at age 26 (more on that in a later post), meaning she was born on or before August 5, 1878, but not any earlier than August 6, 1877. Somehow it seems quite unlikely that Caroline gave birth in August 1877, got almost immediately pregnant, and then had another child ten months after Minnie, but….stranger things have happened. Or perhaps Minnie was adopted. Since I cannot find a birth record for a Minnie Simon in Pennsylvania for either 1877 or 1878, that certainly is a possibility.

In any event, in 1880, Eliza (Wiler) and Leman Simon were living far from their families in Pittsburgh with their five children, Joseph, Flora, Nellie, Minnie, and Leon. Leman was in the liquor sales business, and perhaps life was a little easier out in the western part of Pennsylvania than it was in Philadelphia.

Pittsburgh in 1872 http://www.mapsofpa.com/pittsburgh.htm

Eliza’s younger sister Fanny Wiler married Max Michaelis on July 12, 1874, in Philadelphia. I am still working on Fanny’s story, and there are a lot of holes so that will wait for a later post.

The youngest child of Caroline (Dreyfuss) and Moses Wiler was Clara Wiler, born in 1850. In 1871, she married Daniel Meyers, a German born clothing merchant operating in the 1870s under the firm name D. Meyers and Company. He and Clara were living at 718 Fairmount Street, and their family grew quickly in the 1870s. First, their daughter Bertha was born on December 4, 1972. Less than two years later, their son Leon was born on June 12, 1874, followed the next year by Samuel on December 15, 1875. A fourth child, Harry, was born January 15, 1878, and Isadore on September 25, 1879. Five children in seven years. Wow.

And they were not yet done. But that would bring us into the 1880s, and I am not there yet. But Daniel’s firm must have been weathering the storm of the 1870s depression better than most, including many in the extended family. In 1880, he was supporting five children plus his wife Clara and himself in their house on Fairmount Street.

Thus, the Wiler family like the Pollock family had its ups and downs during the 1870s. There were marriages and babies, but also some economic struggles for at least some of the members of the family. Adult children had to move back home, and some had to leave town to find new opportunities for making a living.

![Ancestry.com. U.S. IRS Tax Assessment Lists, 1862-1918 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2008.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/john-nusbaum-1862-tax.jpg?w=584&h=471)

![Lottie Nusbaum death certificate Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/lottie-nusbaum-death-cert.jpg?w=584&h=552)

![Nusbaum Brothers and Company 1867 Philadelphia Directory Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1821-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/nusbaum-bros-1867.jpg?w=501&h=77)