Did you know that during the Holocaust some German Jews were deported not to the camps in the east, but to France? It was a revelation to me.

I left off my last post with a series of questions regarding the fate of my cousin Johanna Schoenthal and her husband Heinrich Stern, both of whom had been living in a hospice in southern France at the end of World War II. Why did they end up in France, and how long had they been there? How had they survived after the Nazis took over France in the spring of 1940? Who was Henry Kahnweiler, the friend in Paris they named on their 1947 ship manifest when they left France for the US? Had they had children?

Although I don’t have answers to all those questions, thanks to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and the people and sources on JewishGen, I have been able to piece together part of the story of Johanna and Heinrich’s ordeal during World War II.

From the Mannheim Jewish Community database on JewishGen, I learned that Johanna and Heinrich Stern had resided in a town called Karlsruhe before the war. Karlsruhe is about forty miles from Mannheim. It is rather distant from Köln, where Johanna was born—almost 200 miles—and from Giessen, where Heinrich was born. But perhaps more importantly, it is less than twenty miles from the French border. I don’t know how the Sterns ended up living there or when they had moved there.

But I do know when they left. Thanks to Peter Lande at the USHMM, I have learned about a whole new chapter in the history of the Holocaust. Peter sent me the documents below regarding Johanna and Heinrich Stern:

(Translation of first card: Stern, Heinrich, born 3rd August 1876 in Giessen, religion: Jewish, nationality: German – Senior councillor of the Jews in Baden, district South-Baden (source: Nathan Rosenberger, Freiburg: List of survivors of 7.500 deported from the state of Baden), without date, page 3 – ref.-nr. F-18-555 – residence: Karlsruhe, Kleinprechtstr. 41, deported from Karlsruhe at the 22 October 1940 to Gurs in Southern France, current address: Hospice de Romain Drome.

Second card: transport-list from the Gestapo, district Fürstenberg-Baden. ref-nr. VCC 155/XIII. The third card is the same as the first, except it is for Johanna Stern, born 15th of July, 1880 in Köln. )

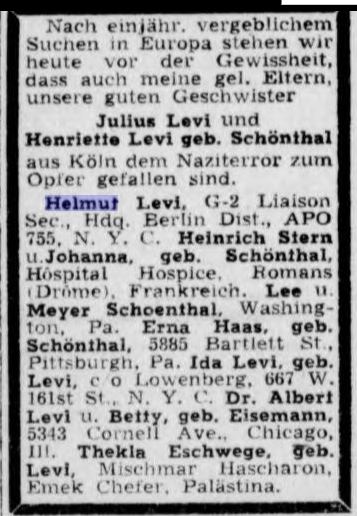

These cards were definitely about my cousin Johanna Schoenthal Stern and her husband Heinrich Stern. The birth dates and places are consistent with the passenger ship manifest and the JewishGen sources I had found, and the place of last residence in Germany and the residence in France are also consistent with those sources and the notice posted by the family in Aufbau in 1946. These cards told me what had happened to Johanna and Heinrich. They had been deported by the Gestapo from Karlsruhe on October 22, 1940, to a place called Gurs in southern France.

With these clues, I was able to find out more about the fate of the Sterns, not specifically but generally. In October, 1940, the Nazi officials in charge of the Alsace and Lorraine regions of France as well as the Baden district of Germany decided to deport the Jews from Baden, having already deported those who had been living in Alsace and Lorraine. This decision, known as the Wagner-Burckel Aktion for the two Nazi officials who planned and implemented it, led to the sudden deportation of approximately 7,500 Jews from the Baden region, including my cousins, the Sterns, who were living in Karlsruhe. It would be the only deportation of German Jews to the west rather than the east of Germany during the Holocaust.

![Railroad tracks to Gurs By Jean Michel Etchecolonea (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/800px-gurs_voie-ferree.jpg?w=584&h=438)

Railroad tracks to Gurs

By Jean Michel Etchecolonea (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Manfred Wildmann, a victim of this deportation, provided this chilling account of the deportation itself on his website Our Lives in Europe:

On October 21, 1940, late in the afternoon, my grandfather, as head of the Jewish community, was told to inform all the Jews of Philippsburg that the next day Jews were not allowed to leave their homes. The next morning the police (it may have been the Gestapo) came to every Jewish house, to inform us that we had one hour to pack after which we would be taken away to an unknown destination.

An hour later, the police came to pick us up to march us to the central square, where a canvas covered truck was waiting for all the 21 Jews of Philippsburg, aged 10 to 80. The truck took us to Bruchsal, 20 km away which was an assembly point for Jews from the area. Late that afternoon, we were all marched to the railroad station. When the train finally came, a passenger train with third class coaches, we were relieved that it was heading south and not north towards Poland. While we didn’t know any details of what was happening in Poland, we knew that whatever it was, it wasn’t good. All night long, the train headed south, stopping often to pick up more Jews along the way. Early in the morning, we crossed the Rhine. Now we knew that we were in France.

Once in France, the deportees were sent to a French detention camp in Gurs in the Basque region of southern France, near the border with Spain. Originally built in 1939 by the French to house refugees from the Spanish Civil War, the camp had also been used by the French to detain German Jews as “enemy aliens” in 1940. After Germany invaded France and the Vichy government was established, the camp came under Vichy control. When the Jews from Baden arrived on nine trains in October 1940, the Vichy government decided to send them to the camp at Gurs.

According to the USHMM website, “Conditions in the Gurs camp were very primitive. It was overcrowded and there was a constant shortage of water, food, and clothing. During 1940-1941, 800 detainees died of contagious diseases, including typhoid fever and dysentery.”

Gurs Detention Camp

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/32/Logor_Gurs.jpg

Manfred Wildmann provided a more detailed and vivid description:

No vegetation grew in the entire Camp, and the constant rain transformed the ground into a sea of mud into which one could sink knee deep and lose one’s shoes.

The barracks of Gurs were of a special construction, with the lower parts of the walls slanting outwards. They were constructed of rough wooden planks, covered with tar paper, with a wooden floor and a few small windows covered with plasticized chicken wire. About eighty people were assigned to each. The only furniture in the barracks was each person’s rolled up straw bag or mattress, suitcases and one cast iron stove in the center to provide a little heat. Everybody lived sitting either on these straw bags or suitcases. This is also how we ate, out of empty tin cans or any other suitable container we could find.

Another family memoir about life at Gurs can be found at The Grey Folder Project website by Toby Sonneman.

In January, 1941, the New York Times reported on conditions at Gurs, noting that there were fifty doctors providing medical treatment to over 7000 people interned in the camp, trying to “reduce an already high and still mounting mortality rate resulting from lack of food and medicine and unhygienic conditions, the physical resistance of most of the refugees already having been worn down through long suffering.” The Times article stated that there were over 500 children in the camp and about 1200 people over seventy. People were suffering from malnutrition, bleeding gums, heart problems, dysentery, typhoid, and lice. There was severe overcrowding and poor heating and ventilation. Fifteen to twenty-five people were dying every day. “Misery and Death in French Camps, ” New York Times, January 26. 1941, p. 24.

What happened to those who survived? According to the USHMM, “1,710 were eventually released, 755 escaped, 1,940 were able to emigrate, and 2,820 men were conscripted into French labor battalions.” The exact number of those who died of the 7,500 Jews who were deported from Baden is not known, but overall over 1000 people died at Gurs over the course of the war. Many of those Baden deportees were transferred to other camps and some eventually to Auschwitz. The USHMM website states, “Between August 6, 1942 and March 3, 1943, Vichy officials turned over 3,907 Jewish prisoners from Gurs to the Germans; the Germans sent the majority of them to the Drancy transit camp outside Paris in northern France. From Drancy, they were deported in six convoys to the extermination camps in occupied Poland, primarily Auschwitz.”

![Cemetery for those who died at Gurs By Jean Michel Etchecolonea (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/1024px-gurs_tombes-3.jpg?w=584&h=438)

Cemetery for those who died at Gurs

By Jean Michel Etchecolonea (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

I don’t know how long Johanna and Heinrich were at Gurs or under what circumstances they were able to leave. Perhaps they were among the 755 who escaped or the 1,710 who were released. Maybe they were transferred to another camp. The records that the USHMM had for them end with the cards posted above.

As for Henry Kahnweiler, the man the Sterns named as their contact person in France on the passenger manifest when they left for the US in 1947, he was the very well-known German-born art dealer, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, described by one source “a banker, writer, publisher, and art dealer who became the pioneering champion of Cubism.” As described by Johanna’s sister, Erna Schoenthal Haas, in the Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle on June 14, 1989, Kahnweiler was a friend of her brother-in-law, Heinrich Stern, from the days they had both been working at a bank in Germany. Kahnweiler’s parents had wanted him to be a banker, but instead he’d moved to Paris in 1907, where he soon established himself as a successful art collector and dealer. He became one of the principal dealers in Cubist art and a major dealer in the works of Picasso.

Here is a portrait of Kahnweiler done by the artist Juan Gris:

Deutsch: Juan Gris: Porträt Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, 32,5 x 26 cm, Bleistift auf Papier, Museée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

During World War I, France appropriated and sold Kahnweiler’s collection because he was a German national and thus a national of an enemy state. After spending the war in exile in Switzerland during which time he wrote several important works on Cubism and art history, Kahnweiler returned to Paris in 1920 and started over. Here is he depicted in 1923 at his gallery in Paris: standing, Daniel Henry Kahnweiler (r), Juan Gris (c) ; 1st row, Louise Leiris (c).

But then in the spring of 1940 when the Nazis invaded France, Kahnweiler, like thousands of other Jews living in France, went into hiding in the south of France. This post describes in detail his ordeal and perhaps reflects the experience of many others including that of Johanna (Schoenthal) and Heinrich Stern. I don’t know how the Sterns stayed in touch with Kahnweiler during the war, but they obviously knew his Paris address in 1947 when they departed for the US.

I imagine that the Schoenthals in the US—especially Lee, Meyer, and Erna—must have been greatly worried about their sister Johanna and her husband during the war, but by June 14, 1946, they knew that Johanna and Heinrich were alive and where they were living, as is apparent from the notice from the Aufbau regarding the deaths of Henriette and Julius Levi. That notice indicates that Johanna and Heinrich were then living in a hospital or hospice in a town called Romans in the department of Drome in southeastern France. I have written to the town of Romans in France to see if they have any information, but so far have not gotten any response.

It was almost exactly a year later that Johanna and Heinrich arrived in the US and settled in Pittsburgh. I can only imagine the joy that the four surviving siblings experienced when they were finally all reunited. A joy, however, that must have been bittersweet, tempered by the knowledge that their sister Henriette and her husband had not survived and that their sister Johanna and her husband must have suffered greatly in order to survive.

In my next post, I will write about the post-war lives of these four siblings, their spouses, and the two grandsons of Jakob and Charlotte Schoenthal, Werner Haas and Helmut Levi/Henry Lyons.

Reblogged this on Janet’s thread and commented:

Surviving the Holocaust.

LikeLike

I’m so glad they were reunited in the US. Interesting detail in this post. I’m fascinated by Kahnweiler, an interesting fellow.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I’d never heard of him before. It’s amazing to me the breadth of topics I learn about while simply learning about my family history!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s hard to tell how large those “buildings” were, but 80 people? Amy, once again, a great post of your family experiences. It gave me chills.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Karen. It is horrifying to learn these things, but important to remember what happened.

LikeLike

Wow, Amy. Your blog is becoming an encyclopedia of “modern” Jewish history! What a stroke of luck in a very unlucky situation. They were truly the exception.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Luanne. As you might imagine, learning that I had so many relatively close cousins—my grandmother’s first cousins and my grandfather’s second cousins—who were directly affected by the Holocaust has been very disturbing.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Final Chapter for Jakob Schoenthal and His Descendants « Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Incredible the amount of information you’ve learned. I have ancestors from Baden so we might just connect the dots after all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, if you know what towns—let me know!

LikeLike

Pingback: Another Delightful Conversation: My Cousin Maxine | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: My Grandmother’s Cologne Cousins: More New Records | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Cologne: Its Jewish History and My Family Ties to the City | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey