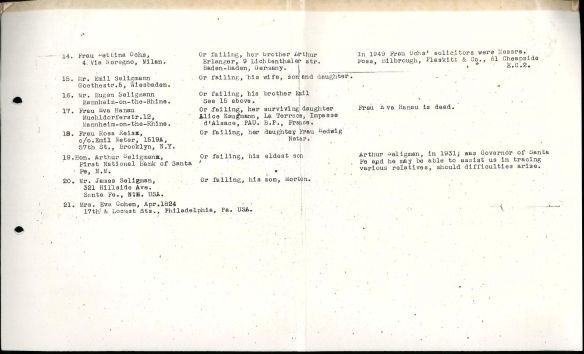

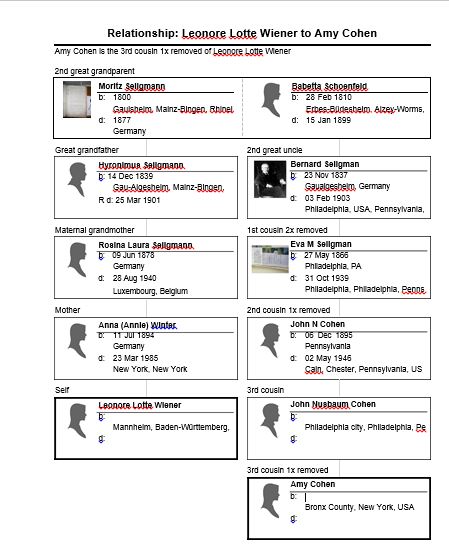

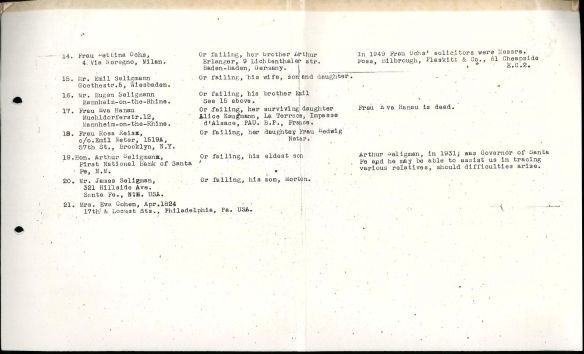

In my last post, I wrote about the list of English James Seligmann’s heirs that my cousin Wolfgang found in his family’s papers. There were 21 principals named as heirs on that document, and I had discussed all the easily identified ones and some of those that were more difficult to figure out. I had discussed Numbers 1, 2, 6-13, 15, 16, 19-21. That left Numbers 3-5, 14, 17, and 18. Here again is the list of heirs:

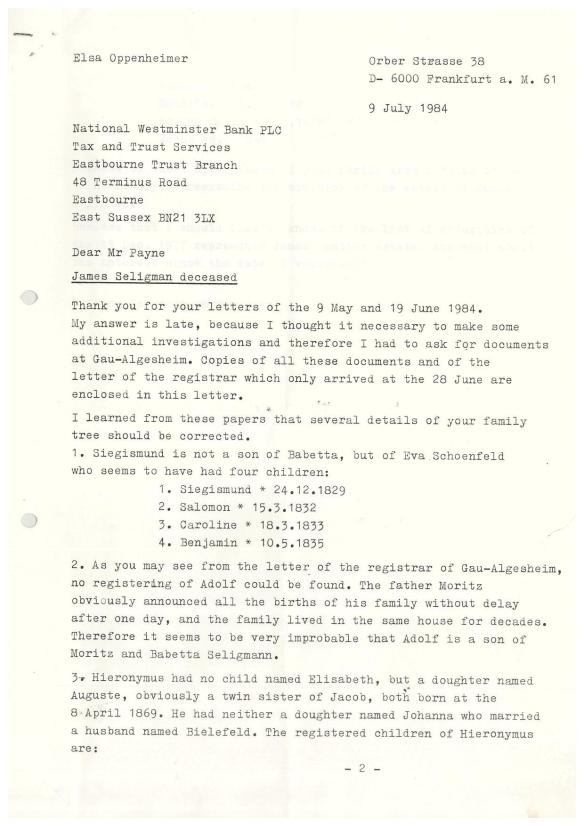

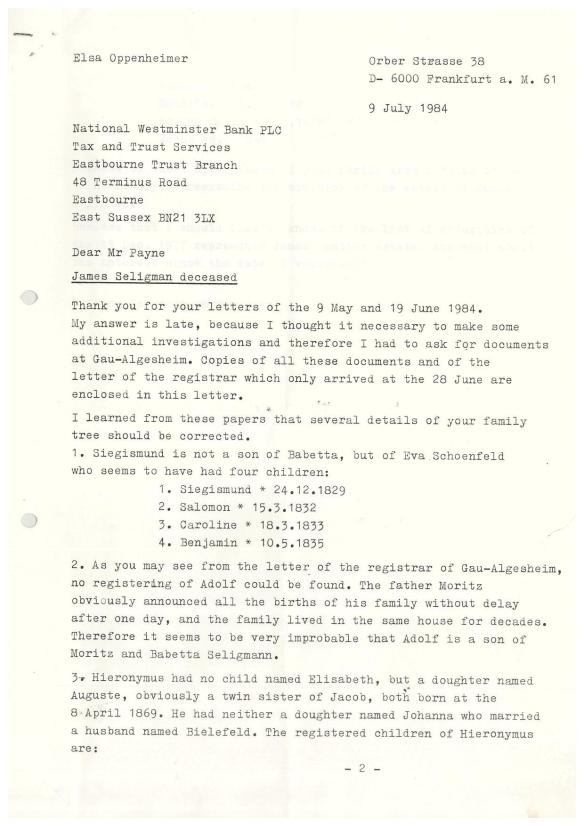

So let’s start with Number 3, Johanna Bielefeld, the one whom Elsa Oppenheimer had claimed was not a daughter of Hieronymus Seligmann in her July, 1984 letter.

Perhaps Elsa was wrong; after all, she was wrong about Adolph Seligman not being the child of Moritz and Babetta, as discussed last time. Or maybe Johanna was the daughter of Benjamin Seligmann. I am not sure yet, but I do know that she was born in Gau-Algesheim. Wolfgang found this registration card for her, dated January 12, 1939, issued by the police in Mainz. It gives her birth name as Seligmann, her birth date as March 15, 1881, and her birthplace as Gau-Algesheim. I have written to my contact in Gau-Algesheim, asking him to see if he can find a birth record for Johanna so I can determine who her parents were. Notice also the large J on her card, indicating that she was Jewish.

Here is the companion card for her husband Alfred Bielefeld:

The list of heirs provided the names of Johanna and Alfred’s children, Hans and Lili (or Lily). It indicated that Johanna had died as had Hans, he in 1948. Then it provided a married name for Lili, Mrs. Fred Hecht, and an address on West 97th Street in New York City. Searching for Hans Bielefeld brought me to someone with that name on the 1940 census, living in Cleveland, Ohio. He was working as an insurance agent, was 37 years old, and had been residing in Mainz, Germany, in 1935.

Year: 1940; Census Place: Cleveland, Cuyahoga, Ohio; Roll: T627_3221; Page: 5A; Enumeration District: 92-451

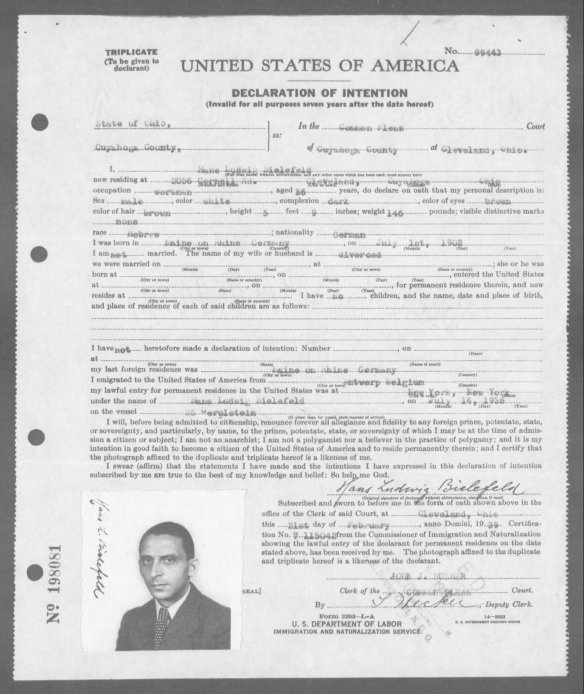

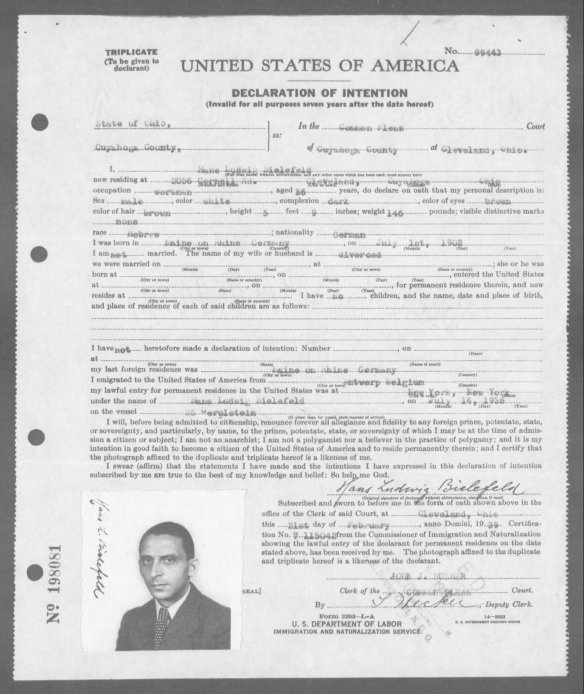

Further searching found an index listing in the Ohio Deaths database on Ancestry for Hans Bielefeld, indicating he had died on September 13, 1948, the same year of death given on the list of heirs document. On Fold3.com, I then found naturalization papers for Hans Ludwig Bielefeld, indicating that he was divorced, that he was born on July 1, 1902 in Maine (sic), Germany, and that he had arrived in the US on the SS Gerolstein on July 14, 1938.

Publication Number: M1995

Publication Title: Naturalization Petition and Record Books for the US District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, Eastern Division, Cleveland, 1907-1946

Content Source: NARA

National Archives Catalog ID: 1127790

National Archives Catalog Title: Naturalization Petitions, compiled 1867 – 1967

Record Group: 21

Partner: NARA

State: Ohio

Court: Northern District, Eastern Division

Catalog Keywords: Petitions Naturalization Immigration Citizenship

Fold3 Publication Year: 2008

That led me to a passenger manifest for the SS Gerolstein, where I found Hans listed as a divorced merchant from Mainz. It seemed like this could be the son of Johanna Seligmann Bielefeld, but I couldn’t be sure.

So I searched for his sister Lili. I first searched for her as Lili Hecht, but had no luck, so I searched for Lili Bielefeld and found her first on an English ship manifest dated September 18, 1940, from Liverpool bound for Montreal, Quebec. Lili was listed as 36, having last resided in London, but born in Germany. Her occupation was given as a domestic. The age, birthplace and name seemed correct, so I considered it likely that this was the right person.

![Ancestry.com. UK, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012.](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/lili-bielefeld-ship-manifest.jpg?w=584&h=38)

Ancestry.com. UK, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012.

Then I found her listed with the same information on a US manifest for passengers entering the United States from Canada. But since Lili did not arrive until September, 1940, she is not listed on the 1940 census, making it extremely difficult to find her in the online databases on Ancestry. There were a number of Fred Hechts, but how would I know if any of them were married to Lili?

So I turned to Google and entered “Lili Bielenfeld Fred Hecht,” and once again I hit the jackpot. Like Fred and Ilse Michel, Fred Hecht and Lili Bielenfeld have papers in the collection at the Leo Baeck Institute entitled “Hecht and Gottschalk Family Collection; AR 5605.” In the biographical note included with this collection, I learned that Fred Hecht came from a German Jewish family with a long history. I will quote here only the sections relevant to Fred, Lili and Hans:

Jakob and Therese Hecht had a son, Siegfried Max Hecht (alternatively Fritz, later Fred, 1892-1970). Siegfried Hecht became a merchant and served in the German military during World War I. Siegfried and his wife Emma née Cahn divorced in 1939, and he immigrated to the United States in 1940, where he took on the name Fred. He settled in New York City and became a jewelry salesman. In December of 1944, he and Lili née Bielefeld (1904-1977) were married.

The Bielefeld family can be traced back to the late 18th century. The family lived in Karlsruhe, Mainz, and Mannheim until the 1930s, when some members immigrated to the United States. Lili Hecht née Bielefeld was the daughter of Alfred Bielefeld, a wine merchant, and Johanna Bielefeld née Seligmann. Despite efforts to procure passage to the U.S., both Alfred and Johanna perished in the Holocaust. Alfred died in Theresienstadt, and Johanna was deported from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz, where she perished.

Lili Hecht née Bielefeld’s brother Hans Ludwig Bielefeld (1902-1948) was a merchant. He married Lilli née Kiritz in 1933, and the couple divorced in 1936. Hans Ludwig immigrated to the United States under the sponsorship of his cousin, Irma Rosenfeld, and settled in Cleveland, Ohio, where he worked in insurance. After his death, his sister Lili Hecht née Bielefeld was the sole heir to the Bielefeld family property, which she claimed in the 1960s alongside restitution for her parents’ deaths.

Thus, from these papers and this biographical note, I was able to find out a great deal about what had happened to Johanna Seligmann Bielefeld, her husband, and her two children, Hans and Lili. I will write more about them in a separate post once I have a chance to examine the LBI collection more carefully and obtain translations where necessary.

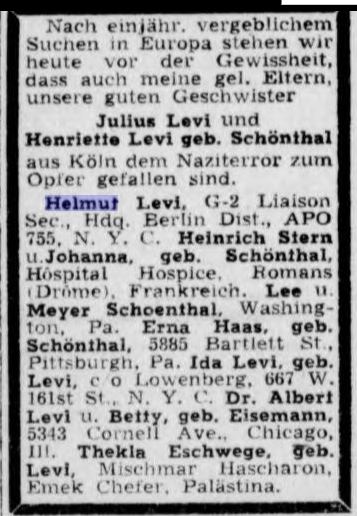

Number 4 on the list, Bettina Arnfeld, was more difficult to locate, but I found a Bettina Elizabeth Arnfeld listed on FindAGrave with the notation, “Body Lost or Destroyed.” Her birthdate was given as March 17, 1875. This may have been the “Elizabeth” whom Elsa claimed was not a child of Hieronymus Seligmann. I then looked for and found Bettina Elizabeth Arnfeld in the Yad Vashem Database. The entries there confirmed that her birth name was Seligmann, that she was born on March 17, 1875, and that she had resided in Muelheim Ruhr in Germany at the time she was deported. She was exterminated at Thieresenstadt on January 23, 1943.

The list of heirs indicated that Bettina had a son, Heinz Arnfeld, living on 22 Gloucester Square in London, and he was not difficult to locate. I found several entries for Heinz and Liselotte Arnfeld at that address in London, England, Electoral Registers on Ancestry. I also found Heinz and Liselotte listed in the England & Wales Marriage Index on Ancestry. They were married in Doncaster, Yorkshire West Riding in 1945. Heinz is also listed as a survivor of the Holocaust in the Shārit ha-plātah database on JewishGen.

Heinz died in 1961 and left his estate to Liselotte; she died in 1988. I do not know whether they had any children. Since they were married in 1945 when Liselotte was 37, it does not seem likely.

That brings me to Numbers 17 and 18 on the list, putting Numbers 5 and 14 aside for now. Who were Eva Hansu and Rosa Reisz? If these were nieces of English James Seligmann, then they had married and changed their surnames, so how could I find them? Since they were listed right after Emil and Eugen, sons of Carolina Seligmann and Siegfried Seligmann, I went back to the list of Carolina’s children and realized that she had daughters named Eva and Rosa. Thus, I assumed that Eva became Eva Hansu and Rosa became Rosa Reisz.

I had good luck searching for Rosa Seligmann Reisz. I knew her daughter’s name was Hedwig Neter from the list of heirs, and that seemed unusual enough that I decided to search for it first. Sure enough the name came up on a passenger’s manifest dated August 31, 1940, for the ship Cameronia departing from Glasgow, Scotland, for New York. Sailing with Hedwig was her husband Emil Neter and her mother Rosa Reis. Emil was a 61 year old manufacturer, Hedwig a 48 year old housewife, and Rosa was 73 without occupation. They all had last been residing in London and said the US was their intended permanent residence.

![Ancestry.com. UK, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012.](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/neter-reis-ship-manifest.jpg?w=584&h=58)

Ancestry.com. UK, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012.

According to FindAGrave, Rosa Seligmann Reis died on January 29, 1958, and is buried at Hauptfriedhof in Mannheim, Germany. Her son-in-law Emil Neter died on July 8, 1971, in Washington, DC, and is also buried at Hauptfriedhof in Mannheim, as is her daughter Hedwig Reis Neter, who died on May 28, 1979, in Washington. I found it very interesting that after living in the United States all those years, Rosa, Emil, and Hedwig chose as their burial place the country they had escaped so many years before. A little more searching turned up Hedwig’s birth certificate and a family record from 1891, both of which revealed that Rosa’s husband’s name was Ludwig Reis, son of Callman Reis, a merchant.

![Ancestry.com. Mannheim, Germany, Births, 1870-1900 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Personenstandsregister: Geburtsregister Standesamt Mannheim und Vororte 1876-1900, Stadtarchiv Mannheim, Mannheim. Deutschland.](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/hedwig-reis-birth-cert.jpg?w=584&h=796)

Hedwig Reis Birth Certificiate Ancestry.com. Mannheim, Germany, Births, 1870-1900 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

Original data: Personenstandsregister: Geburtsregister Standesamt Mannheim und Vororte 1876-1900, Stadtarchiv Mannheim, Mannheim. Deutschland.

![Ancestry.com. Mannheim, Germany, Family Registers, 1760-1900 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Polizeipräsidium Mannheim Familienbögen, 1800-1900. Digital images. Stadtarchiv Mannheim — Institut für Stadtgeschichte, Mannheim, Germany](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/reis-family-register.jpg?w=584&h=912)

Ancestry.com. Mannheim, Germany, Family Registers, 1760-1900 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

Original data: Polizeipräsidium Mannheim Familienbögen, 1800-1900. Digital images. Stadtarchiv Mannheim — Institut für Stadtgeschichte, Mannheim, Germany

Searching at Hauptfriedhof on FindAGrave, I found that Ludwig had died in 1928 and had been buried at Hauptfriedhof. It seems that Rosa and her daughter Hedwig wanted to be buried where Ludwig had been buried years before. With the help of Matthias Steinke in the German Genealogy group on Facebook, I was able to locate the headstone for all four of them at the

Stadtarchiv Mannheim website.

At first I couldn’t find anything about Eva Hansu, Number 17. I couldn’t find her husband’s first name, and although the heirs’ list gives her daughter’s married name as Alice Kauffman of France, I had not been able to find her either. Then after Matthias introduced me to the Stadtarchiv Mannheim website where he had found the headstones for Rosa and her family, I decided to search for all people with the birth name Seligmann and found Eva as Eva Seligmann Hanau, not Eva Hansu as I had mistakenly read it on the list of heirs. It provided the same birth date I’d already found for Eva, March 18, 1861, and it reported her date of death as March 18, 1939. Her husband was Lion Hanau, born May 24, 1854, in Altforweiler, Germany, and he died February 7, 1921. The archive also included photographs of their headstone.

As for their daughter, now that I had the correct spelling of her birth name Hanau, I was able to find her marriage certificate for her marriage to Ernst Kaufmann on August 10, 1911.

Ancestry.com. Mannheim, Germany, Marriages, 1870-1920 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Personenstandsregister: Heiratsregister Standesamt Mannheim und Vororte, Stadtarchiv Mannheim, Mannheim. Deutschland.

I do not know what happened to either Alice or Ernst during or after the war.

So that leaves me with only two names on the list of heirs for whom I as yet have no answers: Anna Wolf, Number 5, and Bettina Ochs, Number 14. Anna Wolf is listed as a fraulein, so that is her birth name, not a married name. It says that Johanna Bielfeld was her aunt, so presumably Anna’s mother was a sister of Johanna. If, in fact, Johanna was a child of Hieronymus Seligmann, she had two sisters, Mathilde and Auguste and perhaps Bettina. I don’t have any information about them aside from what was listed in Elsa’s letter, posted above. More work to be done.

And Number 14, Bettina Ochs, is even more of a puzzle. I’d have assumed that Ochs was her married name, Seligmann her birth name. But the note on the document mentions a brother as her next of kin, and his name was Arthur Erlanger. That would suggest that Bettina Ochs was born Bettina Erlanger, not Seligmann. So how is she related? Who was her husband? Which one is the blood relative of English James Seligmann? I found one listing on JewishGen.org for Bettina Ochs-Erlanger with a secondary name as Bettina Oberdorfer. She was born May 7, 1870, and her nationality was Italian, consistent with the Milan address provided on the heirs list. She was listed in the Switzerland, Jewish Arrivals, 1938-1945 database; I can’t see the original document, but the index indicates that she arrived in Switzerland on August 5, 1944.

It’s amazing how much information I could mine from this one little document. Unfortunately, although I should have gotten great satisfaction from finding so many people and so much information, I ended up feeling very sad and very drained as I added all these names of my cousins to the list of those killed in the Holocaust. It is beginning to overwhelm me. So much loss, so much evil. Incomprehensible.

![Railroad tracks to Gurs By Jean Michel Etchecolonea (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/800px-gurs_voie-ferree.jpg?w=584&h=438)

![Cemetery for those who died at Gurs By Jean Michel Etchecolonea (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/1024px-gurs_tombes-3.jpg?w=584&h=438)

![Gilabrand at en.wikipedia [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/08/kkl_tin.jpg?w=584)

![Ancestry.com. UK, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012.](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/lili-bielefeld-ship-manifest.jpg?w=584&h=38)

![Ancestry.com. UK, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012.](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/neter-reis-ship-manifest.jpg?w=584&h=58)

![Ancestry.com. Mannheim, Germany, Births, 1870-1900 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Personenstandsregister: Geburtsregister Standesamt Mannheim und Vororte 1876-1900, Stadtarchiv Mannheim, Mannheim. Deutschland.](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/hedwig-reis-birth-cert.jpg?w=584&h=796)

![Ancestry.com. Mannheim, Germany, Family Registers, 1760-1900 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Polizeipräsidium Mannheim Familienbögen, 1800-1900. Digital images. Stadtarchiv Mannheim — Institut für Stadtgeschichte, Mannheim, Germany](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/reis-family-register.jpg?w=584&h=912)