Many of you enjoyed the memoirs and other writings of my cousin Lotte Furst, which are posted here, here, here, and here. You will recall that Lotte and her family lived in Mannheim, Germany, and were living a comfortable life in a good home; Lotte’s father was a doctor, and her mother was the granddaughter of Hieronymous Seligmann, younger brother of my great-great-grandfather Bernard Seligman. When the Nazis came to power, Lotte’s life changed forever. After suffering through years of anti-Semitism and deprivation of their rights, her family finally decided to leave Germany and came to the United States. Lotte’s writings described in vivid terms her perspective on all of this as she experienced it as a young girl and then as a young woman.

I recently learned that Lotte’s older sister Doris also wrote a memoir. Doris was four years older than Lotte, and thus I was curious as to how her perspective was like or different from that of her younger sister. When Hitler came to power in 1933, Doris was seventeen and thus would have had a more adult-like view of things. Doris died in 2007, and her daughter Ruth was kind enough to share her mother’s memoirs with me. Much of it is quite personal, so I am going to focus on those sections that provide insights into the larger questions: what was life like before Hitler came to power, how did it change when he did, and what led to the decision to leave Germany? [All material quoted from Doris Gruenewald’s writings is protected by copyright and may not be used without the permission of her children.]

Doris was born in October 1916 in Mannheim; Germany was in the midst of World War I, and her father, Joseph Wiener, was drafted into the German army as a medical officer soon after she was born. Her mother, Annie Winter Wiener, went with Doris to live with her parents, Samuel and Laura (Seligmann) Winter in Neunkirchen, where Samuel owned a women’s clothing business. Annie’s brother Ernst had recently been killed while serving in the German army after volunteering against his parents’ wishes. Doris wrote:

He had been the apple of their eyes and his death dealt a terrible blow to both. My grandmother wore only black from then on, and my grandfather’s health began to deteriorate. They also lost their sizable fortune, having bought war bonds as their patriotic duty, which at the end of the war were not worth anything anymore. My grandfather’s business was dissolved and then reestablished on a much smaller scale.

Ernst Winter

Courtesy of Lotte Furst

Doris compared her grandparents’ home in Neunkirchen with her own home in Mannheim:

The house in Neunkirchen had a large garden in back of it, most of which was rented out. The smallest part, directly behind the house, was used for growing some vegetables and flowers. I remember loving to play in the garden and watching earthworms after a rain as well as other living creatures. In Mannheim there was little opportunity for this kind of nature watching as we lived in a built-up urban area with little greenery, other than a well laid out park some distance from our apartment.

Neunkirchen

For several years while the French occupied parts of Germany after World War I, several family members housed French soldiers, and the neighborhood school Doris would have attended was also being used by the French military. Thus, she had to go to a school somewhat further from her home for those years. Like her sister Lotte, Doris pursued a highly academic path in school and was one of only six girls out of thirty students in her Gymnasium classes and then the only girl in her class when she reached the final years of her pre-university level education.

This excerpt provides a sense of the family’s lifestyle:

My parents employed a cook and a housemaid, and when my sister and I were still young, a “Kinderfraulein” who used to be an untrained young woman with an interest in children. In other words, not quite a “governess.” My father had help in his office and for some time also employed a driver after he developed a painful condition in his left arm, due to having to reach outside the car for shifting gears. ….

We had a Bechstein Grand piano in our living room. This instrument had been given to my mother as a young girl. She had really wanted to study music on a professional basis. But her parents felt that “proper” young ladies did not take up that kind of profession and did not allow her to pursue her wish. Instead, they bought her the Bechstein and let her have piano lessons.

I began taking piano lessons at age seven, with a teacher considered among the best in Mannheim. My mother, although an accomplished pianist, no longer played much. But occasionally, she and my father, who had learned to play the violin in his youth, would play duets together. That always was a special treat.

I was particularly interested in what Doris wrote about the role of Judaism in the family’s life.

I grew up through the years with some awareness that we were Jewish, without knowing what significance that had then and later. Neither my parents nor my grandparents when I knew them observed any religious tenets. However, I was told that in past years my grandfather had been the head of the Jewish Congregation in Neunkirchen. My grandmother, who was president of the local Red Cross chapter for some time, used to fast on Yom Kippur. She reluctantly told me, when I kept asking her, that she had promised her dying mother to keep that tradition. As for me, I was kept home on the Jewish High Holy Days. My family did not attend any services. ….

At eight years of age I happened to be visiting my grandparents at the time of Passover. They had been invited by friends to a large Seder. Unfortunately, nobody thought of explaining to me what that was all about. My grandparents may have assumed that I knew, but I did not. I understood nothing of what was being read in Hebrew or spoken in German. I was utterly bored! Furthermore, when the ceremony asked for tasting the so-called bitter herbs, I bit off a piece of the horseradish on my plate and soon experienced the consequences of that act!

Unfortunately, I think far too many children, here in the US and elsewhere in the world, have that experience at seders.

The family was, however, required to provide some religious instruction because of the school system’s requirements:

There having been no separation of Church and State, religious instruction was part of the official curriculum. The students were separated one period per week according to their denominations. Most were Protestants, some were Catholics, and a few were Jewish. Since the number of Jewish children was so small, and in the case of my first-grade placement non-existent, my parents were required for that year to hire a private instructor in order to comply with the legal requirement. Thus, there suddenly appeared a not very clean looking young man with a greasy book, from which he proceeded to read and attempt to teach me-at six years of age-the Hebrew text. My recollection is that he came to our house only a very few times. I do not know how the religious instruction requirement was fulfilled after that disaster.

When, at fourth grade level, I changed schools, religion was taught by a little old man, a retired rabbi, who was very nice and even made some of what he taught rather interesting. But I developed no feeling for or interest in it at all, as it was totally divorced from the rest of my life.

Then, as Lotte also described, their father decided to withdraw from the Jewish community:

When I was fourteen, my father had some kind of a dispute with the Jewish Community, which was the official agency for collecting taxes. These taxes were legally mandated as a percentage of one’s general income tax obligation. I nearer knew exactly what the problem was, except that it had something to do with the amount owed, to which my father was apparently objecting. The Rabbi came to our house to straighten the matter out. Apparently he was not successful as subsequent events proved. (This rabbi became my brother-in-law at a much later time. He knew that I was far removed from religious observance, but he was always very tolerant and friendly to me.)

Whatever the problem had been, my father decided to leave the Jewish Congregation. Since I was already fourteen years old, I was required to state my personal intention. As I had no ties to the Jewish community, that was no problem for me. From then on I was without any religious affiliation, called “konfessionslos.” In practical terms it meant that I no longer had to attend religious instruction at school. I used the weekly free hour to visit the Art Gallery opposite the school building and saw a lot of very interesting, good art works.

Dr. Joseph Wiener Courtesy of Lotte Furst

Of course, the family’s withdrawal from the Jewish community and lack of religious involvement did not make any difference in the eyes of the Nazis once they came to power. Doris wrote:

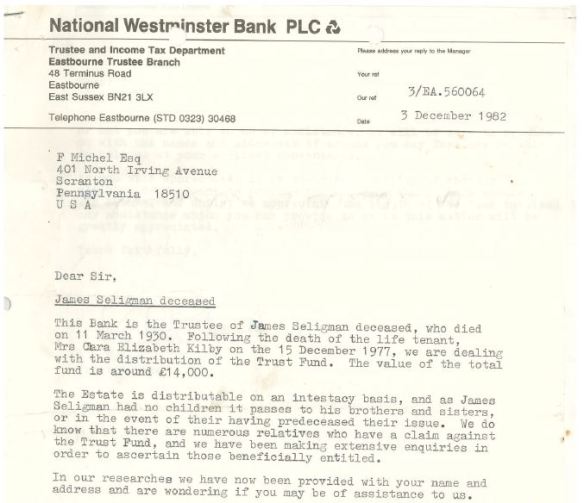

Between 1932 and 1935 I had a valid German passport, used during those years primarily for trips to the Saar to visit my grandparents and take the then permitted two hundred German marks to be deposited outside Germany. In those years the Saar was still under the administration of a French post-World-War I governing authority. My grandmother took care of such transactions. By the time I needed a new passport, the Nazis had decided that a big “J” had to be stamped on any so-called non-Aryan, meaning Jewish, person’s passport. Word had gotten around that one of the clerks in the passport office in Mannheim would issue a “clean” document without the dreaded J, for suitable consideration. I went to that office, saw the clerk in question, and for the small sum of five marks was issued a regular passport without the J. I still have this passport as a memento.

When the Nazis assumed power in 1933, we as a family re-joined the Jewish Congregation as a matter of honor. Not that it would have made any difference had we not done so as the Nazis classified people not necessarily by religion but by their so-called racial identity.

An example of German Jewish passport. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

As Doris approached the end of her time in the local schools in the 1930s, she was both the only girl and the only Jew in her class. She wrote that things did not change dramatically at school despite the political changes around them, but she did describe one troubling incident:

I entered the classroom in the morning, as usual. Upon approaching my desk, I saw that someone had pasted a viciously antisemitic sticker from the “Sturmer,” a rabidly anti-Jewish paper, on my desk. By that time, one of my classmates had begun wearing the SS uniform. I more or less assumed that he was the culprit, which in the end turned out not to have been the case. However, at that moment I decided not to confront him or anyone else. I sat down at another desk and waited for the right time to act. This came with the second period when the “Klassenlehrer”-the equivalent of our Home Room teacher-was due for his hour. … I waited for this teacher outside the classroom and told him my reason for doing so, adding that I knew there was nothing I could do about official policy and insults, but that I was not willing to put up with personal attacks.

This teacher, who, incidentally, had been an officer in World War I and had lost an arm, rose to the occasion. He and I entered the classroom together, and he immediately asked who had done this deed. Somewhat to my surprise, and perhaps his too, not one of the students admitted having put the sticker on my desk. There was nothing further he could have done: I do not remember whether he spoke to the class, but his earlier behavior had given ample proof of his opinion. … The incident occurred about one week before the final exam, the Abitur. It cast a pall over that important event.

Embed from Getty Images

Imagine being the only girl and the only Jew in the class and standing up for herself that way. What courage it must have taken to do this. What if her teacher had not been sympathetic? Despite this stressful incident, Doris successfully passed the Abitur. Although Doris was entitled to enroll in the university based on her father’s military service during World War I, Jews were prohibited from enrolling in either law school or medical school. Instead, Doris decided to audit a few courses while awaiting a visa to leave Germany. She wrote:

I had known for some time that I had to get out of Germany as there was no future there for me, and I was willing to take whichever came first [she had applied for both a US visa and a certificate to immigrate to Palestine]. However, I admit that I was relieved when the American visa materialized first.

The American Consulate closest to Mannheim was located in Stuttgart. In due course I was summoned for an interview with the American consular officials. I was in a somewhat unusual position in that my father had learned of a legal means of transferring money abroad, which was then discounted at the rate of fifty percent. The permissible amount was sufficient to enable me to show the U.S. Consulate that I had the requisite five thousand dollars for obtaining an immigration visa to the U.S. In this way I did not have to await my application number to come up in regular order, which would have taken a great deal more tame. I got my visa rather quickly. By that time I had also received a so-called Affidavit of Support from one of my grandmother’s cousins, whose father had emigrated in the nineteenth century and had settled in Cleveland, Ohio. This cousin was in very good financial circumstances and readily responded to our request for an affidavit. …

I was very interested in determining who this cousin might have been. If she was Laura Seligmann Winter’s cousin, she might have also been a cousin of mine, depending on whether she was a paternal cousin or not. The only clues I had from Doris’ memoir were her married name (Irma Rosenfeld), her residence in Cleveland, her children: a son who was in his 20s in 1937, a daughter who was married, and another daughter who was a student at Vassar.

I found one Irma Rosenfeld living in Cleveland at that time who had two daughters and a son and was married to a man named Mortimer Centennial Rosenfeld (I assume the middle name was inspired by the fact that Mortimer was born in 1876, the centennial of the Declaration of Independence). I sent Lotte the photo from that Irma’s passport application, but Lotte was unable to confirm from the photograph that it was the right Irma Rosenfeld.

![Irma Rosenfeld and daughter passport photo 1924 Ancestry.com. U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2007. Original data: Selected Passports. National Archives, Washington, D.C.](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/irma-rosenfeld-and-daughter-helen.jpg?w=313&h=213)

Irma Rosenfeld and daughter passport photo 1924

Ancestry.com. U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2007.

Original data: Selected Passports. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

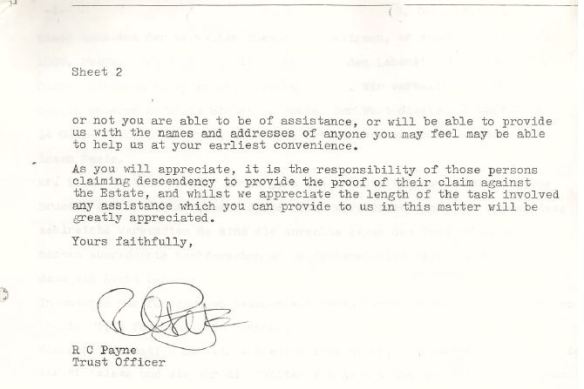

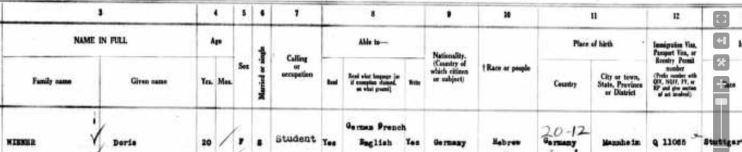

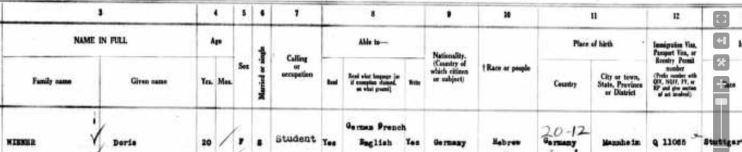

After reading Doris’ memoir, I went back to all the documents I had for her and examined more closely the passenger manifest for her trip to the US in 1937. I had not seen the second page of it my first time through, but this time I noticed that it not only named Irma Rosenfeld; it had her street address in Cleveland. It only took a glance at the 1940 US census for me to confirm that I had in fact found the correct Irma.

Doris Wiener 1937 ship manifest part one

![p2 Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897.](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/doris-wiener-ship-manifest-p-2.jpg?w=709&h=267)

p2

Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897.

A little more research revealed that Irma’s birth name had been Irma Levi, daughter of Isaac Levi and Fanny Loeb. Since Doris and Lotte’s great-grandfather (and my three-times great-uncle) Hieronymous Seligmann had married a woman named Anna Levi, I believe that that is the connection between Doris and Irma. Anna Levi was a contemporary of Isaac Levi; perhaps they were siblings, and thus Irma Rosenfeld would have been a first cousin, twice removed, of Doris and Lotte, their grandmother Laura’s first cousin. Obviously, the family had stayed in touch with these American cousins, and even though Irma was American-born and had never met Doris before, she reached out to help her escape the Nazi regime.

Continuing now with Doris and her emigration from Germany:

Necessary preliminaries having been taken care of and good-byes having been said, it was time to arrange for the journey to America. We bought a ticket for me on the SS Washington, a twenty-thousand ton ocean-going passenger boat, and also obtained railroad tickets for me and my mother who wanted to accompany me to Cherbourg, the place of embarkation. …

In Cherbourg I said good-bye to my mother, for whom the separation was very hard, more so than for me. For one thing, I was looking toward something new. But perhaps more importantly, I had unwittingly insulated myself to some degree from the impact of events. This condition lasted for a long time and to some extent gave me some emotional protection….

In contrast to so many, I confess that I had an easy time. Not only was the way for coming to America smoothed. My parents also were well able to pay for my ticket and whatever other expenses arose in connection with my leaving. I was twenty years old at that time. …

Doris Wiener and her mother Courtesy of Lotte Furst

Doris explained why her parents and sister did not come with her:

The question has often been asked why my parents and sister did not come at the same time. Like a great many people, my father kept believing that the Hitler episode was just that, and he refused for a long time to see the situation realistically. Not so my mother. She was instrumental in organizing their own as well as her parents’ emigration to Luxembourg, and later their own to America.

Doris wrote that she arrived in New York in 1937 with $400. Her parents had arranged for friends to meet her at the boat, and Doris stayed with them for a week before moving to her own apartment on the top floor of a building at 96th Street and Central Park West. Doris also described a visit to Cleveland to see her grandmother’s cousin, Irma Rosenfeld, the woman who had provided the affidavit in support of Doris’ visa, as discussed above. “The slightly more than four weeks I spent with the Rosenfelds were very pleasant, with visits to their country club and other social activities.” But Doris preferred to remain in New York City.

After returning to New York, Doris soon found employment in a dentist’s office and also soon met her future husband, Ernst Gruenewald. They were married in May 1938. Her mother Annie came to New York for the wedding, not only to witness the wedding but also “to gain insight into the international situation uninfluenced by German propaganda.”

My mother had intended to stay in America for about six weeks. But as she listened to the broadcasts available to us, she became increasingly agitated and decided to cut her visit short in order to initiate their emigration from Luxembourg to the United States. She had always been a very intelligent woman capable of making important decisions, many of which were advantageous. She returned to Luxembourg and was able to convince my father that this was the right thing to do. They arrived in the U.S. in April 1939, three weeks after the birth of our first child and about half a year before the outbreak of World War II.

Her grandparents, as we know from Lotte’s memoirs, did not fare as well:

During my childhood I had spent a good deal of time with them in Neunkirchen and was very fond of my grandmother. I knew her only from her mid-forties on, when in my eyes she was an old lady. She was a very reserved but warm person and managed their life very competently. My grandfather was a short, slim man who from the time I knew him as a person, was not well. … My grandparents had applied for a visa to the United States before the outbreak of World War II, but failed to be granted immigrant status. In retrospect, I am convinced that my grandfather’s condition was the reason, as they had enough money to qualify for a visa. My parents also could have vouched for them. My grandfather ended up in Theresienstadt, where he died of pneumonia, as we were told after the war. My grandmother had suffered a fatal heart attack while still living in Luxembourg.

Doris and her husband Ernst and their family ended up relocating from New York to Chicago for a business opportunity a few years after her parents and Lotte arrived . During the 1950s, Doris went back to school and obtained her bachelor’s degree while also raising her children; in 1961 she received a masters’ degree in psychology as well. She then went on to get a Ph.D. in psychology, specializing in neuropsychology, which was itself still a relatively new field. After obtaining her degree, she worked at Michael Reese Hospital in the Adult Inpatient department where she eventually became the director. Sadly, after twenty years there, she found herself forced out on the basis of their mandatory retirement age. She had just turned seventy.

In 1987 Doris and Ernst moved to California, where the winters were milder and where her sister Lotte was living. Doris had obtained a California license before moving and was able to continue to practice as a psychologist when they moved, but did so only for a short period before retiring. Ernst died in 1989, and Doris died almost twenty years later in 2007.

It was fascinating to me to read Doris’ memoirs after reading Lotte’s; both sisters wrote so clearly and so powerfully about their lives. I can see that they had much in common: great intelligence, dedication to hard work and to family, astute powers of observation, and a love of language. Doris struck me as the more thick-skinned of the two sisters, often talking about her independence and emotional distance from others, even as a young child. Doris wrote about being somewhat of a loner and keeping her thoughts and feelings to herself. I would imagine that those qualities served her well as she endured her teen years in Hitler’s Germany and a voyage alone to America in 1937 as well as her adjustment to life in America.

Overall, I am struck by how strong these two women were, both as children in Germany, as new immigrants to the US, and as women experiencing all the changes that came in the years after World War II. I’d like to think some of that is the Seligmann DNA that we share, but I doubt that I would have been as resilient and brave as they had to be, if I had had to endure the challenges and hardships they did.

![Iserlohn By No machine-readable author provided. Asio otus assumed (based on copyright claims). [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC BY-SA 2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/iserlohn-muehlentor1-asio.jpg?w=584)

![Buchenwald Watch Tower undesarchiv, Bild 183-1983-0825-303 / CC-BY-SA 3.0 [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/buchenwald.jpg?w=584)

![Crematoria at Majdanek death camp near Lublin, Poland Deutsche Fotothek [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/majdanek-crematoria.jpg?w=584&h=368)

![By Snapshots Of The Past (Parade Place and Kaufhaus Karlsruhe Baden Germany) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/08/parade_place_and_kaufhaus_mannheim_baden_germany.jpg?w=584)

![By Annaivanova (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/1024px-bechstein_576_grand_piano_franz_liszt_-_klavier.jpg?w=584&h=330)

![Irma Rosenfeld and daughter passport photo 1924 Ancestry.com. U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2007. Original data: Selected Passports. National Archives, Washington, D.C.](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/irma-rosenfeld-and-daughter-helen.jpg?w=313&h=213)

![p2 Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897.](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/doris-wiener-ship-manifest-p-2.jpg?w=709&h=267)

![By Zol87 from Chicago, Illinois, USA (Michael Reese Hospital) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/1024px-michael_reese_hospital_02.jpg?w=584&h=438)