Some families seem to suffer more misfortune than others. This is one of those families. It is the story of the family of Mathilde Dreyfuss, sister of my three-times great-grandmother Jeanette, and her family. Her first husband was John Nusbaum’s brother Maxwell Nusbaum, making this particular line related to me both on my Dreyfuss side and my Nusbaum side. That is, Mathilde and Maxwell’s children are my double first cousins, four times removed.

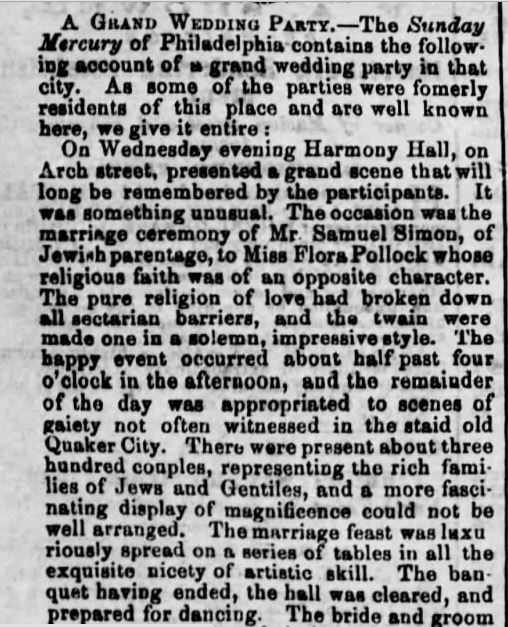

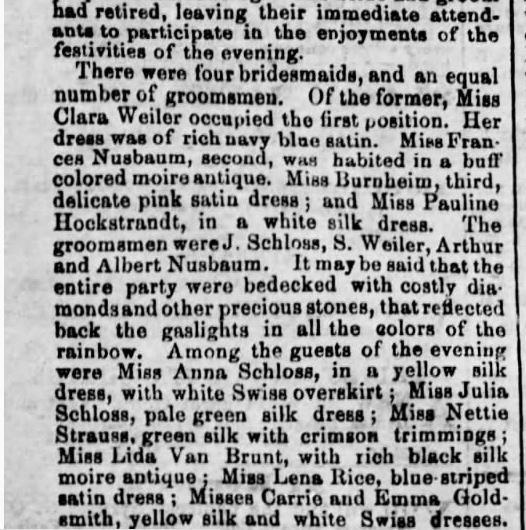

As I have written, Maxwell Nusbaum and Mathilde Dreyfuss had two children, a daughter Flora born in 1848 and a son Albert born in 1851. Less than seven months after Albert’s birth, Maxwell died in the 1851 Great Fire in San Francisco. By 1856 Mathilde had married Moses Pollock, with whom she had three more children, Emanuel, Miriam, and Rosia. The family lived in Harrisburg for many years, but by 1866 had relocated to Philadelphia.

In the 1870s, the Pollocks were living in Philadelphia where Moses was a dry goods merchant. Their youngest child Rosia died in 1871 when she was just five months old.

Pennsylvania, Philadelphia City Death Certificates, 1803-1915,” index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/JK3P-DBS : accessed 22 January 2015), Rosie Pollock, 26 Feb 1871; citing 1075, Philadelphia City Archives and Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; FHL microfilm 2,020,735.

Mathilde’s daughter Flora had married Samuel Simon, one of the three brothers to marry into the Nusbaum/Dreyfuss clan, and they had two children in the 1870s, Meyer (mostly likely named for his grandfather Maxwell) and Minnie. By 1880, Flora and Samuel had moved to Elkton, Maryland, where Samuel was running a hotel. Meanwhile, Moses and Mathilde (Dreyfuss Nusbaum) Pollock were still in Philadelphia, and the other surviving children—Albert Nusbaum and Emanuel and Miriam Pollock—were still living at home with them, according to the 1880 census. Moses was in the cloak business, Albert was in the liquor trade, and Emanuel was in the dry goods business. Moses’ line of trade seemed to change to trimmings or finishings during the 1880s and 1890s with various directories listing his businesses as plaiting, laces, embroidery, school bags, and accordion pleating.

Mathilde’s family was struck by tragedy again on September 1, 1885, when Miriam Pollock, just 26 years old, died from consumption or tuberculosis. Mathilde had lost her first husband to a fire, her daughter Rosia at five months, and then her daughter Miriam at 26. Sometimes life is just not fair.

“Pennsylvania, Philadelphia City Death Certificates, 1803-1915,” index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/JFSV-LHQ : accessed 22 January 2015), Miriam Pollock, 01 Sep 1885; citing , Philadelphia City Archives and Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; FHL microfilm 2,070,682.

Then Moses Pollock died on December 5, 1894 of encephalomalacia, defined in Wikipedia as “localized softening of the brain substance, due to hemorrhage or inflammation.” Like so many other family members, he was buried at Mt. Sinai cemetery in Philadelphia. He was 69 years old.

“Pennsylvania, Philadelphia City Death Certificates, 1803-1915,” index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/JKS4-32N : accessed 22 January 2015), Moses Pollock, 05 Dec 1894; citing cn 11116, Philadelphia City Archives and Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; FHL microfilm 1,872,200.

Both Albert Nusbaum and Emanuel Pollock had continued to live with their parents throughout the 1880s and 1890s, and in 1900, they and their mother were still living together at the same address, 934 North Eighth Street. Mathilde, now widowed twice in addition to losing two children, was working outside the house as a manufacturer of bags—presumably, the school bags listed as one of the items Moses was selling on the last directory entry before his death. Albert was still a liquor salesman, and Emanuel was selling bicycles. In addition, Meyer Simon, Flora’s son and Mathilde’s grandson, now 30 years old, was also living with them and was working with his grandmother in the bag manufacturing business as a manager.

Mathilde’s daughter Flora Nusbaum and her husband Samuel Simon, meanwhile, had left Elkton, Maryland, and moved to Baltimore by 1885. Samuel was in the liquor business, as was his brother Moses, who was married to Paulina Dinkelspiel, Flora’s first cousin.[2] My hunch is that they were business together.

In 1900, Samuel was still in the liquor business in Baltimore, but his brother Moses had died the year before. Samuel and Flora still had their daughter Minnie living at home with them, but their son Meyer, as noted above, was living in Philadelphia with his grandmother and uncles Albert and Emanuel and managing the bag manufacturing business.

Although Meyer Simon was listed as single on the 1900 census, the 1910 census reported him as married for 12 years. I figured that this must have been a mistake, especially since he was still living at his grandmother’s address even in the 1901 directory. It seemed he could not have been married for 12 years in 1910.

But then I found something strange. After some further research and review, I found in the Pennsylvania, Marriages 1709-1940 data base on familysearch.org a marriage between Meyer Simon and Tillie Perry on September 18, 1897, in Allegheny, Pennsylvania. Meyer’s wife’s name on the 1910 census was Matilda, so I knew this was the correct marriage. Matilda or Tillie Perry was the daughter of William and Matilda Perry; she was born in Philadelphia in 1876 and baptized in the Episcopal church in 1878. But if Meyer and Matilda were married in 1897, why was Meyer listed as single on the 1900 census, and where was Matilda?[3]

I found Matilda Perry on the 1900 census living with her parents in Philadelphia, and that census report stated that she was married and had been married for three years, which is consistent with the marriage record I found on familysearch. Had Meyer and Matilda married and then lived separately for at least three years? It seems strange, but perhaps they could not yet afford a place of their own. Or perhaps they were temporarily separated. Or perhaps the religious differences had made it difficult for those families to support the marriage. After all, Meyer listed his marital status as single. I suppose it is also possible that he had kept the marriage a secret from his family. After all, they were married in Allegheny, not in Philadelphia or in Baltimore where their families lived. Allegheny was a city across the river from Pittsburgh that merged with Pittsburgh in 1907. It would have been therefore over 300 miles from Philadelphia and about 250 miles from Baltimore.

Thus, as of 1900, Mathilde Dreyfuss Nusbaum Pollock was a widow, living in Philadelphia with her two sons, Albert and Emanuel. Her daughter Flora was living with her husband Samuel Simon in Baltimore with their daughter Minnie, and their son Meyer was married, but not yet living with his wife Matilda.

The decade that followed must have been a very painful one. First, on March 21, 1904, Mathilde Pollock died. She was 79 years old. The death certificate says she died of old age, which shows you how perspectives on aging and longevity have changed. It also says that she died from “senile pneumonia,” a term for which I could find no easily understood definition for my non-medical brain to grasp, but which I gather is a form of pneumonia that affects the elderly. (Feel free to provide a more scientifically accurate definition.) The death certificate also says that Mathilde had ascites, another term not easily defined but which Wikipedia defines as “gastroenterological term for an accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity.” Don’t even get me started on trying to understand where the peritoneal cavity is, but from what I read, ascites seems to have something to do with liver disease, often cirrhosis.

Mathilde’s death was followed three years later by the death of her son Emanuel Pollock on February 16, 1907. He was only fifty years old and died of tuberculosis. Three years after that his half-brother Albert Nusbaum died on August 28, 1910 from apoplexy brought on by arteriosclerosis. He was 59 years old. Mathilde and both of her sons were buried at Mt. Sinai cemetery.

That left only Flora Nusbaum Simon as the surviving child of Mathilde Dreyfuss Nusbaum Pollock. She had lost both of her parents and all four of her siblings. She was also the only child who had children of her own as none of her siblings ever married or had children. Flora and Samuel appear to have relocated from Baltimore to Philadelphia by 1905, the year after her mother died, as Samuel appears in the Philadelphia directory living at 2225 North 13th Street, the same address where the family is listed in the 1910 and 1920 census reports.

Flora’s brother Albert had been living with them at that address in April when the 1910 census was taken, just four months before he died. Neither Samuel nor Albert nor anyone else in the household was employed at that time, yet they still had a servant living in the home. Minnie, Flora and Samuel’s daughter, was 27 and single, living with her parents and uncle. It feels like it must have been a very sad time for the family.

Flora and Samuel’s son Meyer and his wife Matilda were living about two miles away at 2200 Susquehanna Avenue in 1910. Meyer was a clothing salesman. There were two boarders living with them, but no children. When Meyer registered for the World War I draft in 1917, he and Matilda were living at 3904 North Marshall Street, two and a half miles north of his parents and his sister. Meyer was employed as a clothing salesman for Harry C. Kahn and Son, according to his draft registration.

On February 18, 1919, Flora Nusbaum Simon suffered yet another loss when her husband Samuel Simon died from a cerebral hemorrhage at age 79. She and her daughter Minnie were living together in 1920 at their home at 2225 North 13th Street. Flora herself died almost four years to the day after her husband Samuel on February 20, 1923. She was 74 years old and died from chronic interstitial nephritis. She had outlived all of her siblings by over 13 years. She, like all the rest of them, was buried at Mt. Sinai cemetery with her husband Samuel.

![Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/flora-nusbaum-simon-death-cert.jpg?w=584&h=540)

Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

After her mother Flora died, Minnie Simon lived with her brother Meyer and his wife Matilda in the house on North 13th Street where Flora had died, number 2336, across the street from where they had lived for many years at 2225. Meyer was employed as a clothing salesman, and his niece Matilda (a fifth Matilda in his life) was also living with them. Meyer lost his sister Minnie six years later when she died from liver cancer on December 14, 1936; she was 63 years old.

Meyer was the only member of his family left. He had no siblings, no nieces or nephews on his side. It must have been just too much for him when his wife Matilda then died on April 27, 1940, at age 63 from cerebral thrombosis and chronic nephritis. Two years later on June 2, 1942, Meyer took his own life. He was found on the second floor of his home at 2336 North 13th Street with a gunshot wound to his head. He had no survivors. Although Meyer was buried with his family at Mt. Sinai, he was not buried with his wife Matilda. She was buried at a non-denominational cemetery instead (Northwood); because she was not Jewish, she could not be buried at Mt. Sinai. How sad.

Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

This story fills me with such sadness. How lonely Meyer must have been. He’d lost his grandparents, his parents, his aunts and uncles, his sister, and his wife. And there were no children or nieces or nephews left to comfort him. Certainly there were other Nusbaum cousins nearby in Philadelphia, but it must not have been enough.

From the start of the story of the life of Meyer’s grandmother Mathilde Dreyfuss, this family suffered such tragedy: Maxwell’s death in the Great Fire of San Francisco and two daughters who died young. Of Mathilde’s four children who grew to adulthood, only Flora married and had children, and there were no grandchildren to carry on the family line after Flora and Samuel Simon and their two children Meyer and Minnie died. There are no living descendants of Mathilde Dreyfuss or Maxwell Nusbaum. No one likely remembers their names. Except now they have been found and can be remembered for the tough lives they lived and for the courage and hope they must have had when they arrived in Pennsylvania in the middle of the 1800s.

[1] Isaac died without any children in 1870, so unfortunately that was the end of that sibling’s line.

[2] Flora’s father Maxwell Nusbaum was the brother of Paulina Dinkelspiel’s mother, Mathilde Nusbaum Dinkelspiel.

[3] Poor Meyer had at least four Mathilde/Matildas in his life: his mother, his wife, his mother-in-law, and one of his aunts. And today I don’t know one woman named Mathilde or Matilda or Tillie.

![Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/alfred-levy-death-cert.jpg?w=584&h=450)

![Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/miriam-levy-death-certificate.jpg?w=584&h=437)

![Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/flora-nusbaum-simon-death-cert.jpg?w=584&h=540)

![Ancestry.com. U.S. IRS Tax Assessment Lists, 1862-1918 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2008.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/john-nusbaum-1862-tax.jpg?w=584&h=471)

![Lottie Nusbaum death certificate Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/lottie-nusbaum-death-cert.jpg?w=584&h=552)

![Nusbaum Brothers and Company 1867 Philadelphia Directory Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1821-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/nusbaum-bros-1867.jpg?w=501&h=77)