As of 1933 when Hitler came to power in Germany, five of Sara Rothschild and Moses Adler’s surviving children were still living in Germany: Caroline (Grete), Malchen, Emmi, David Theodore, and Betty. Their oldest three children—Louis, Sigmund, and Julius—had long ago emigrated to the United States. Fortunately, all five of those still in Germany were able to leave in time.

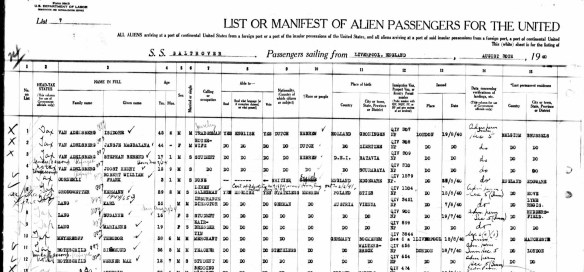

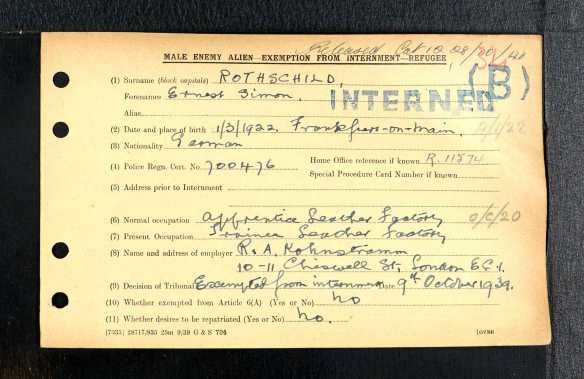

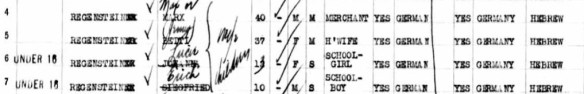

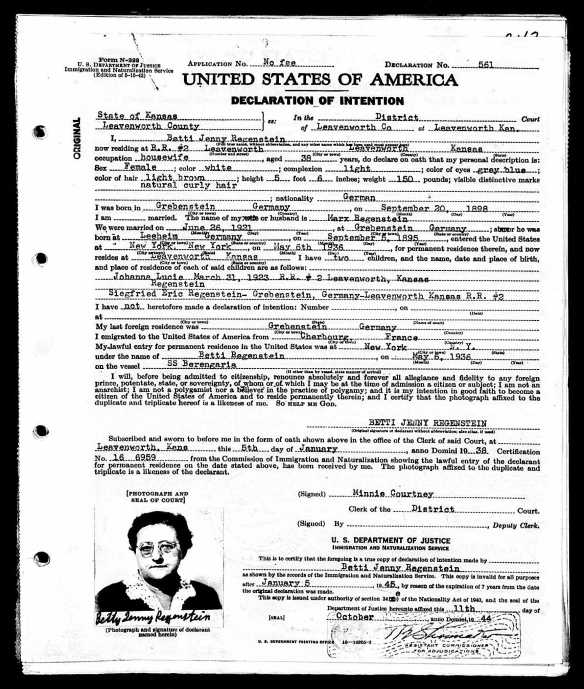

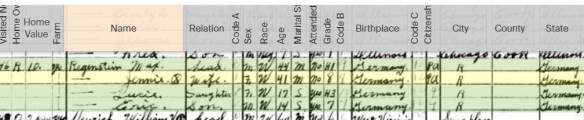

Interestingly, Betti, the youngest of those still in Germany, was the first to leave. She, her husband Marx Regenstein, and their two children Lucie and Erich sailed from Cherbourg, France, on April 29, 1936, and arrived in New York on May 6, 1936. Notice that all the first names were changed on the manifest. Marx became Max, Betti became Jenny, and Lucie was no longer Johanna, Erich no longer Siegfried. Max listed his occupation as a merchant on the ship manifest. They listed their destination as Leavenworth, Kansas, identifying Betti/Jenny’s brother Louis Adler as the person they were going to.

Regenstein family passenger manifest, The National Archives in Washington, DC; Washington, DC, USA; Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957; Microfilm Serial or NAID: T715; RG Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004; RG: 85, Ship or Roll Number: Berengaria, Ancestry.com. New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957

I found it heartwarming to learn that Louis, who had left his family behind in 1900 when he was fifteen, was still in touch with his siblings back home. Just as he had taken in his brother Julius after Julius lost his first wife, Louis once again seemed to take on the role of assisting a sibling. In January 1938, when Betty declared her intention to become a US citizen, she and her family were still living in Leavenworth, Kansas.

Betti Jenny Regenstein Declaration of Intention, National Archives at Chicago; Chicago, Illinois; ARC Title: Petitions For Naturalization, 1906-1991; NAI Number: M1285; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685-2009; Record Group Number: Rg 21, Petitions, V· 1243-1245, No· 309401-309950, 1944, Ancestry.com. Illinois, U.S., Federal Naturalization Records, 1856-1991

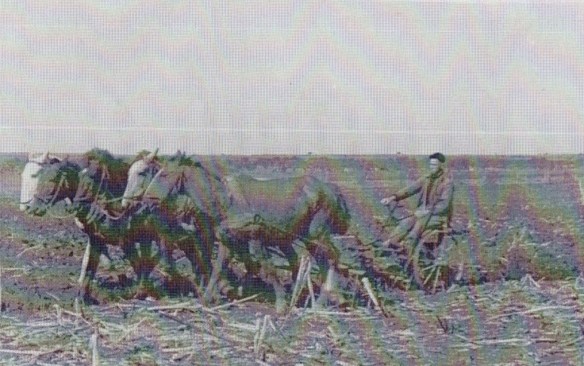

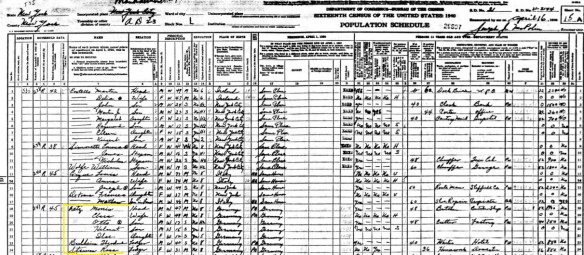

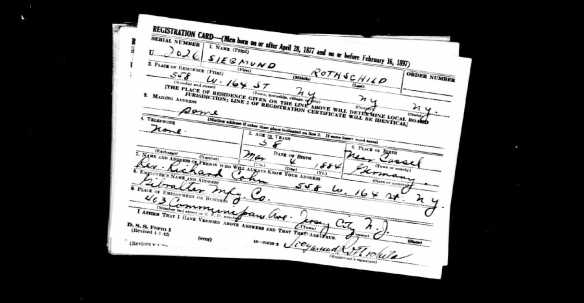

But two years later in 1940, Betti (now listed as Jennie), Marx (now Max), and their children Lucie and Eric were living in Covert, Michigan, where Max was working as a farmer. I don’t know what drew them to that location. In 1935 they’d been living in Chicago, according to the census report. At first I thought it was Betti/Jenny’s brother Sigmund who had drawn them to Michigan since at one point he had been living in Ishpeming, Michigan, but that is very distant from Covert, and besides, by 1940 Sigmund was living in Connecticut.

Regenstein family, 1940 US census, Year: 1940; Census Place: Covert, Van Buren, Michigan; Roll: m-t0627-01822; Page: 3A; Enumeration District: 80-13, Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census

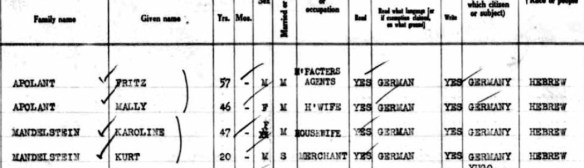

The next Adler siblings to leave Germany were Caroline Grete and Malchen. They sailed together from Cherbourg on April 14, 1937, with Malchen (Mally)’s husband Fritz Apolant and Caroline (Karoline) Grete’s son Kurt. Caroline’s husband Albert Mandelstein had died on October 20, 1934, in Grebenstein; he was 79.1 Fritz listed his occupation as a manufacturer’s agent, and Kurt Mandelstein, who was twenty, listed his as a merchant. Like Betti before them, they all listed Leavenworth, Kansas, as their destination, and Louis Adler as the person to whom they were going.

Mandelstein and Apolant passenger manifest, The National Archives in Washington, DC; Washington, DC, USA; Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957; Microfilm Serial or NAID: T715; RG Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004; RG: 85, Ship or Roll Number: Queen Mary, Ancestry.com. New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957

I have to confess that until I saw this ship manifest, I’d had no idea that Sara Rothschild and Moses Adler had a daughter named Caroline Grete. Somehow in my initial search for their children, Caroline had eluded me. It was only when I saw her listed on that ship manifest that I realized I’d missed a child and went back and found her records.

I don’t know whether or not Caroline or Malchen ever actually went to or lived in Leavenworth, Kansas. When Caroline filed her declaration of intention on October 20, 1937, just six months after arriving in New York on April 19, 1937, she and her son Kurt were living in Chicago, Illinois.

Similarly, when Malchen’s husband Fritz Apolant filed his declaration of intention on October 14, 1937, they were living in Chicago.

Fritz David Apolant declaration of intention, National Archives at Chicago; Chicago, Illinois; ARC Title: Petitions For Naturalization, 1906-1991; NAI Number: M1285; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685-2009; Record Group Number: Rg 21

Petitions, V· 1079-1081, No· 268890-269400, 1942, Ancestry.com. Illinois, U.S., Federal Naturalization Records, 1856-1991

I don’t know what drew them to Chicago, but I did notice that one of the witnesses on Malchen’s naturalization papers was a man named Benjamin “Nandelstein.” Perhaps that was really Mandelstein, as the signature appears to be, and this was a relative of her sister Caroline’s deceased husband Albert Mandelstein.

Affidavit of Witnesses for Malchen Apolant naturalization, National Archives at Chicago; Chicago, Illinois; ARC Title: Petitions For Naturalization, 1906-1991; NAI Number: M1285; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685-2009; Record Group Number: Rg 21, Petitions, V· 1192-1195, No· 297765-298328, 1943, Ancestry.com. Illinois, U.S., Federal Naturalization Records, 1856-1991

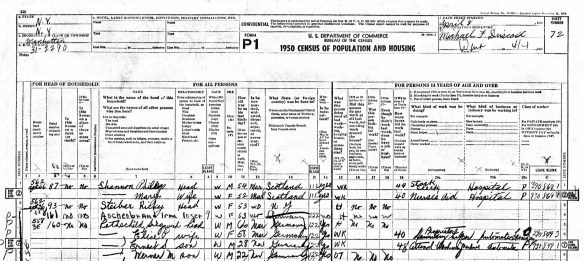

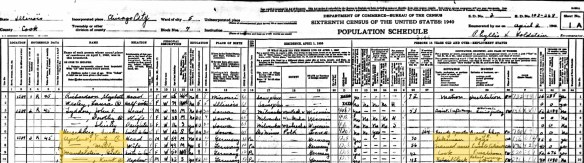

In any event, in 1940, Fritz, Malchen (Mally), Caroline (Grete now), and Kurt were all living together in Chicago, and all four were working. Fritz was an egg salesman, Mally a nurse for a private patient, Grete a cook in a private home, and Kurt a clerk in a retail grocery store.

Apolant and Mandelstein on 1940 US census, Year: 1940; Census Place: Chicago, Cook, Illinois; Roll: m-t0627-00929; Page: 1A; Enumeration District: 103-268, Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census

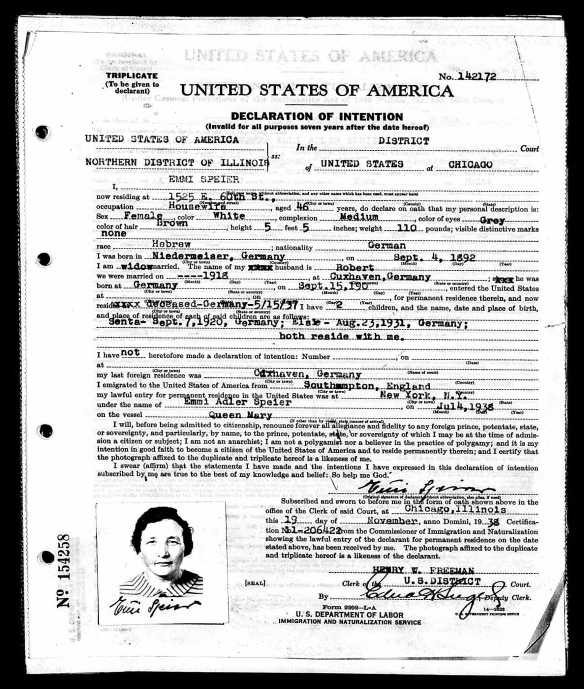

The next sibling to arrive in the US was Emmi Adler Speier. Like her older sister Caroline Grete, Emmi was a widow when she immigrated to the US. Her husband Robert Speier had died on May 15, 1937, in Guxhagen, Germany; he was only 47 when he died.2 Emmi and her two children, Ilse/Elsie and Senta, and her sister-in-law Lea Speier all sailed from Easthampton, England, on June 29, 1938. They arrived in New York on July 4, 1938, an auspicious date to arrive in the US. Like her other sisters, Emmi listed her brother Louis as the person she was going to and Leavenworth, Kansas, as her destination. She listed her brother T. [Theodore] Adler as the person she left behind.

Speier family passenger manifest, The National Archives in Washington, DC; Washington, DC, USA; Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957; Microfilm Serial or NAID: T715; RG Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004; RG: 85, Ship or Roll Number: Queen Mary, Ancestry.com. New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957

But Emmi and her children also did not end up in Leavenworth for long, if at all. By November 19, 1938, she also was living in Chicago, as were her two daughters.

Emmi Adler Speier declaration of intention, National Archives at Chicago; Chicago, Illinois; ARC Title: Petitions For Naturalization, 1906-1991; NAI Number: M1285; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685-2009; Record Group Number: Rg 21

Petitions, V· 1180-1183, No· 295150-295735, 1943, Ancestry.com. Illinois, U.S., Federal Naturalization Records, 1856-1991

In 1940, Emmi was living in Chicago with Ilse and Senta, along with three lodgers. Ilse was working as a dressmaker.3

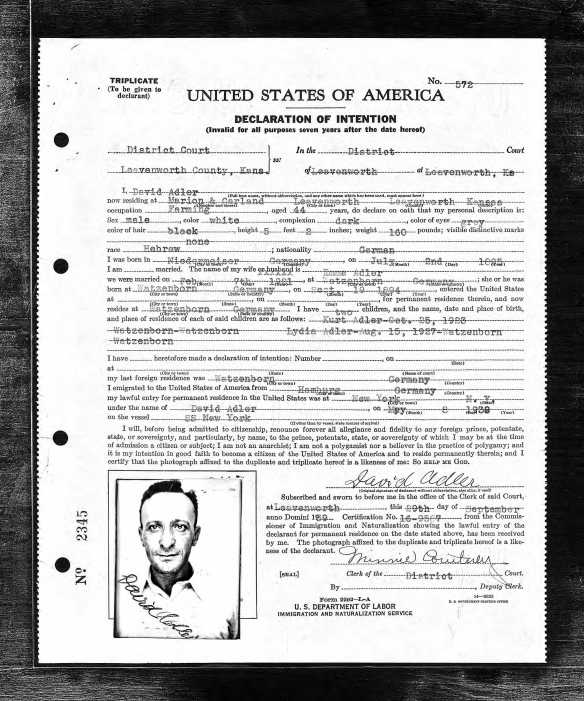

Finally, the last sibling to arrive was the remaining son of Sara Rothschild and Moses Adler, their son David Theodore Adler. He sailed without his wife Emma on April 30, 1939, arriving in New York on May 8, 1939. He listed his wife Emma as the person he had left behind and his brother Louis Adler in Leavenworth, Texas, as the person he was heading to; his occupation was a dealer.4 David did in fact go to Leavenworth, where on September 29, 1939, he filed his declaration of intention. He listed his occupation as a farmer.

David Theodore Adler declaration of intention, National Archives at Chicago; Chicago, Illinois; ARC Title: Petitions For Naturalization, 1906-1991; NAI Number: M1285; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685-2009; Record Group Number: Rg 21

Petitions For Naturalization, V· 1224, No· 305251-305500, Ca· 1943-1944, Ancestry.com. Illinois, U.S., Federal Naturalization Records, 1856-1991

But in 1940, like his other siblings Grete (Caroline), Malchen, Emmi, and Betty, David Theodore (now just using Theodore) was living in Chicago, working as a laborer doing odd jobs.5

All five of the younger children of Sara Rothschild and Moses Adler were reunited in one city. What would their lives in America bring for them and their children?

To be continued.

-

Albert Mandelstein, Gender männlich (Male), Death Age 79, Birth Date abt 1855

Death Date 20 Okt 1934 (20 Oct 1934), Death Place Grebenstein, Hessen (Hesse), Deutschland (Germany), Civil Registration Office Grebenstein, Spouse Grete

Certificate Number 27, Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv; Wiesbaden, Deutschland; Personenstandsregister Sterberegister; Signatur: 3080; Laufende Nummer: 909, Ancestry.com. Hesse, Germany, Deaths, 1851-1958 ↩ - Robert Speier, Death Age 48[sic], Birth Date 15 Sept 1889, Death Date 15 Mai 1937 (15 May 1937), Death Place Guxhagen, Hessen (Hesse), Deutschland (Germany, Civil Registration Office Guxhagen, Certificate Number 12, Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv; Wiesbaden, Deutschland; Personenstandsregister Sterberegister; Bestand: 2869; Laufende Nummer: 920, Ancestry.com. Hesse, Germany, Deaths, 1851-1958 ↩

- Emmi Speier, 1940 US census, Year: 1940; Census Place: Chicago, Cook, Illinois; Roll: m-t0627-00929; Page: 4A; Enumeration District: 103-267, Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census ↩

- David Adler, passenger manifest, The National Archives in Washington, DC; Washington, DC, USA; Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957; Microfilm Serial or NAID: T715; RG Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004; RG: 85, Ship or Roll Number: New York, Ancestry.com. New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957 ↩

- Theodore Adler, 1940 US census, Year: 1940; Census Place: Chicago, Cook, Illinois; Roll: m-t0627-00930; Page: 7A; Enumeration District: 103-303, Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census ↩