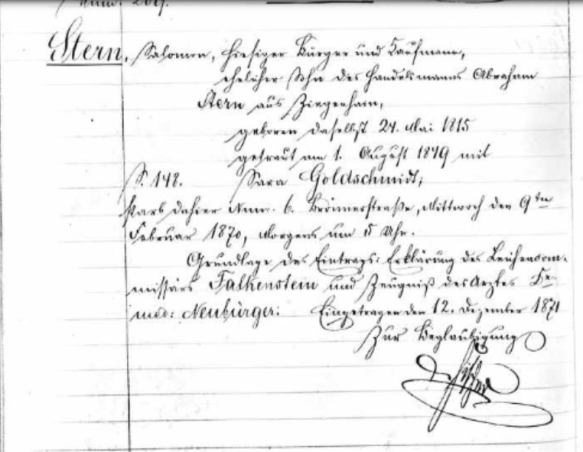

In this post, I will focus on the two daughters of Sarah Goldschmidt and Salomon Stern, Lina and Keile, and their lives and the lives of Keile’s family between 1910 and 1930 in Germany.

Lina Stern Brinkmann

We saw last time that Lina lost her husband Levi Brinkmann on September 14, 1907, when she was fifty-five years old. Lina and Levi had not had children, and the only other record I have for Lina is her death record. She died on January 31, 1935, in Frankfurt, Germany. She was 84 years old. Lina experienced the first few years of Nazi reign in Germany. I wonder if in some way it hastened her death.

Lina Stern Brinkmann death record, Personenstandsregister Sterberegister; Bestand: 903; Signatur: 11044, Ancestry.com. Hesse, Germany, Deaths, 1851-1958

Keile Stern Loewenthal

We also saw last time that Lina’s sister Keile had lost her husband Abraham Loewenthal in the first decade of the 20th century. He was survived by Keile and their five children: Selma, Julius, Helen, Siegfried, and Martha.

Selma Loewenthal was married to Nathan Schwabacher and had three children: Alice, Julius, and Gerhard.

UPDATE: Thanks to the generosity of her great-granddaughter Carrie, I am able to share these photographs of Selma, Nathan, and their children and grandchildren.

Selma Loewenthal Courtesy of her family

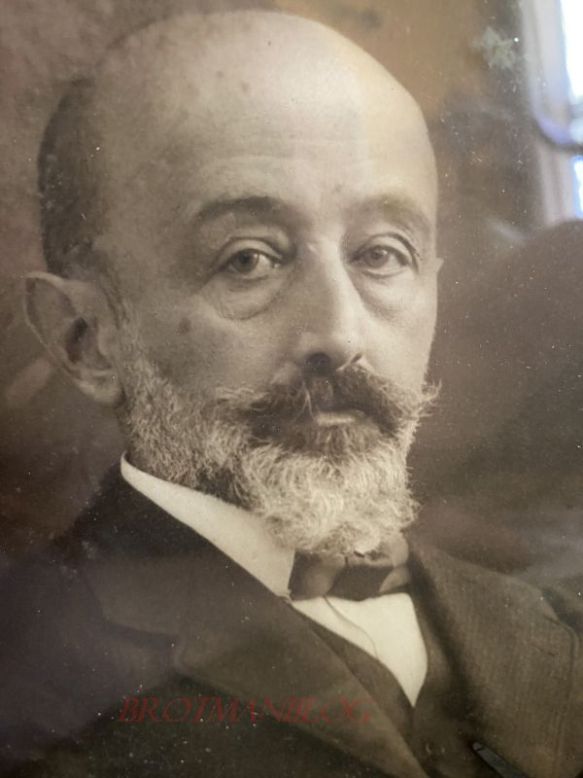

Nathan Schwabacher

Alice Schwabacher

Gerhard Schwabacher Courtesy of the family

Julius Schwabacher

Wolfgang Weinstein and dog

Eva Lore Schwabacher Courtesy of the family

Selma Loewenthal Schwabacher Courtesy of the family

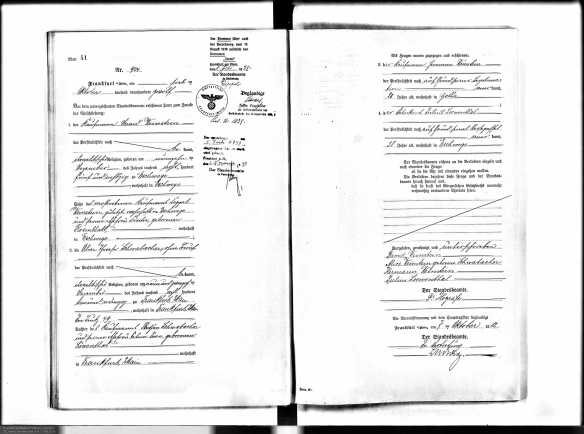

Alice Schwabacher married David Weinstein on October 7, 1912, in Frankfurt. David was the son of Cappel Weinstein and Cecelia Weinstein and was born in Eschwege on December 19, 1885.

Marriage record of Alice Schwabacher and David Weinstein , Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv; Wiesbaden, Deutschland; Bestand: 903, Ancestry.com. Hesse, Germany, Marriages, 1849-1930

Alice and David had one son, Wolfgang Carl Weinstein, born in Eschwege on November 9, 1913. He was Keile’s first great-grandchild.1

Julius Schwabacher married Margarete Wurtemberg on September 20, 1920, in Erfurt Germany. Margarete was born in that city in 1894; I could not find the names of her parents.2 Margarete gave birth to Eva Lore Schwabacher on June 11, 1921, in Frankfurt.3 But the marriage between Julius and Margarete did not last, and they were divorced in 1928.4

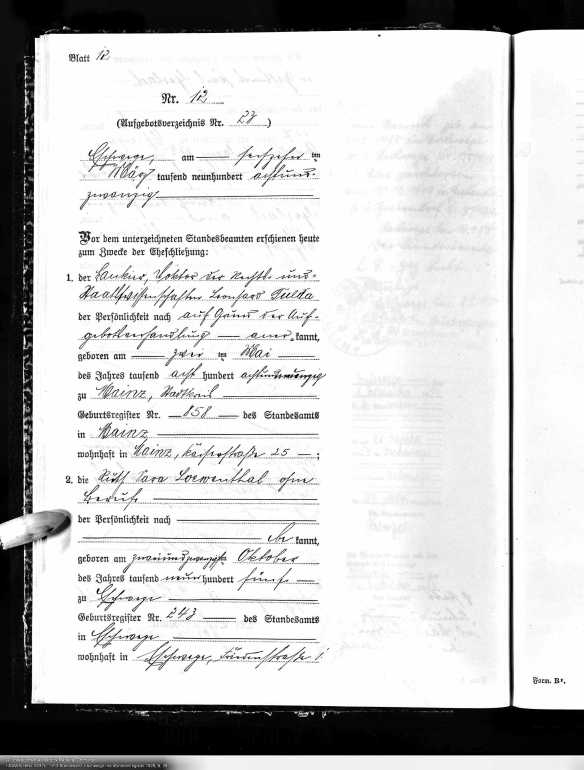

Julius Loewenthal and his wife Elsa Werner, had two children before 1910, Ruth and Herbert, and two more before 1920. Hilda Henriette Loewenthal was born on October 22, 1911,5 and Karl-Werner Loewenthal, who was born on February 14, 1918, in Eschwege.6 Only Ruth married before 1930. She married Leonhard Fulda on March 16, 1928, in Eschwege. Leonhard was the son of Isaac Fulda and Johanna Rosenblatt, and he was born May 2, 1898, in Mainz, Germany.

Marriage Record of Ruth Loewenthal and Leonhard Fulda, Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv; Wiesbaden, Deutschland; Bestand: 923; Laufende Nummer: 1913

Ancestry.com. Hesse, Germany, Marriages, 1849-1930

Marriage Record of Ruth Loewenthal and Leonhard Fulda, Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv; Wiesbaden, Deutschland; Bestand: 923; Laufende Nummer: 1913 Ancestry.com. Hesse, Germany, Marriages, 1849-1930

Helene Loewenthal had married Eduard Feuchtwanger in 1897, but it appears that that marriage did not last. On October 9, 1913, Helene married Oskar Friedrich August Heinrich Maximilian Schultze. As you can see from the marriage record, Oskar was not Jewish, but “evangilische,” Protestant.

Helene Loewenthal Feuchtwanger marriage to Oskar Friedrich August Heinrich Maximilian Schultze, Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv; Wiesbaden, Deutschland; Bestand: 925; Laufende Nummer: 2493, Ancestry.com. Hesse, Germany, Marriages, 1849-1930

Helene and Oskar had one child, Elisabeth Auguste Aloysia Schultze born on December 3, 1914, and baptized on May 12, 1915, in Koblenz, Germany.

Birth record of Elisabeth Schultze, Description: Taufen, Heiraten u Tote 1869-1920

Ancestry.com. Rhineland, Prussia, Lutheran Baptisms, Marriages, and Burials, 1533-1950

Siegfried Loewenthal’s family also continued to grow in the 1910s. He and his wife Henriette Feuchtwanger had two more children in that decade, following the births of the first three children, Rosel in 1908 and Albert in 1909, and Louise Sarah Loewenthal in 1910, all in Frankfurt. Grete was born on April 16, 1913, and lastly, Lotte Loewenthal was born on October 3, 1914.7

UPDATE: Aaron Knappstein located Grete’s birth record.

Martha Loewenthal, Keile’s fifth and youngest child, and her husband Jakob Wolff did not have any additional children after 1910. Their three children Anna, Hans Anton, and Hans Walter, were growing up in that decade.

Thus, by 1920, Keile had fifteen grandchildren and one great-grandchild. The 1910s had been good to her and her children. But 1920 brought the next loss to the family when Nathan Schwabacher, Selma’s husband and Keile’s son-in-law, died on March 6, 1920, at the age of sixty.8

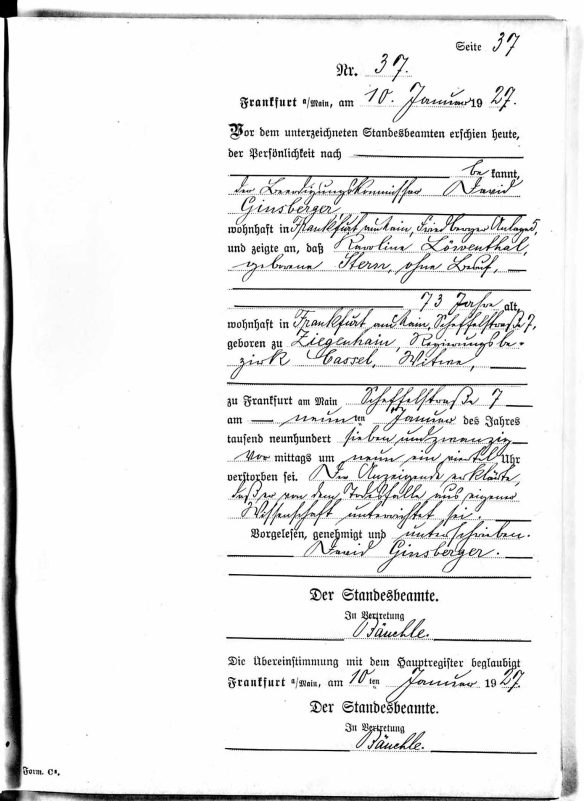

The decade ended with two big losses for the family. Keile Stern Loewenthal died on January 9, 1927, in Frankfurt; she was 73. She was survived by her five children, sixteen grandchildren, and one great-grandchild with more to come.

Keile Stern Loewenthal death record, Personenstandsregister Sterberegister; Bestand: 903; Signatur: 10926, Ancestry.com. Hesse, Germany, Deaths, 1851-1958

And her daughter Martha died three years later on May 19, 1930. She was only 47 years old and was survived by her husband Jakob Wolff and their three children.9

UPDATE: Aaron Knappstein also located Martha’s actual death record.

For Keile’s other children, Selma, Julius, Helene, and Siegfried, and for their children, the 15 years after Keile’s death in 1927 would bring many challenges and much heartache when life for Jews in Germany was forever altered by the rise of Hitler and Nazism.

Before we turn to that era, let’s catch up with Keile’s siblings, Sarah Goldschmidt’s sons, Abraham Stern and Mayer Stern, and their families.

- SSN: 041105870, Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007 ↩

- Julius Schwabacher naturalization papers, The National Archives at Philadelphia; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; NAI Title: Declarations of Intention for Citizenship, 1/19/1842 – 10/29/1959; NAI Number: 4713410; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685-2009; Record Group Number: 21, Ancestry.com. New York, State and Federal Naturalization Records, 1794-1943 ↩

-

SSN: 045121672.

Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007 ↩ - See footnote 2. ↩

- National Archives and Records Administration; Washington, DC; NAI Title: Index to Petitions for Naturalizations Filed in Federal, State, and Local Courts in New York City, 1792-1906; NAI Number: 5700802; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685-2009; Record Group Number: RG 21, Description: (Roll 1126) Petition No· 304900 – Petition No· 305314, Ancestry.com. New York, State and Federal Naturalization Records, 1794-1943 ↩

- Arolsen Archives, Digital Archive; Bad Arolsen, Germany; Lists of Persecutees 2.1.1.1; Series: 2.1.1.1, Reference Code: 02010101 oS, Ancestry.com. Europe, Registration of Foreigners and German Persecutees, 1939-1947 ↩

- Grete’s birthdate comes from her immigration file at the Israel Archives, found at https://www.archives.gov.il/en/archives/#/Archive/0b07170680034dc1/File/0b07170680a31bed. Lotte’s birth date appears in several documents including at Arolsen Archives, Digital Archive; Bad Arolsen, Germany; Lists of Persecutees 2.1.1.1; Series: 2.1.1.1, Reference Code: 02010101 oS, Ancestry.com. Europe, Registration of Foreigners and German Persecutees, 1939-1947. ↩

-

Death record of Nathan Schwabacher, Certificate Number: 426,

Personenstandsregister Sterberegister; Bestand: 903; Signatur: 10828,

Ancestry.com. Hesse, Germany, Deaths, 1851-1958 ↩ - Translated death record located in Jakob Wolff’s immigration file at the Israel Archives, found at https://www.archives.gov.il/en/archives/#/Archive/0b07170680034dc1/File/0b07170680e4ea29 ↩