be

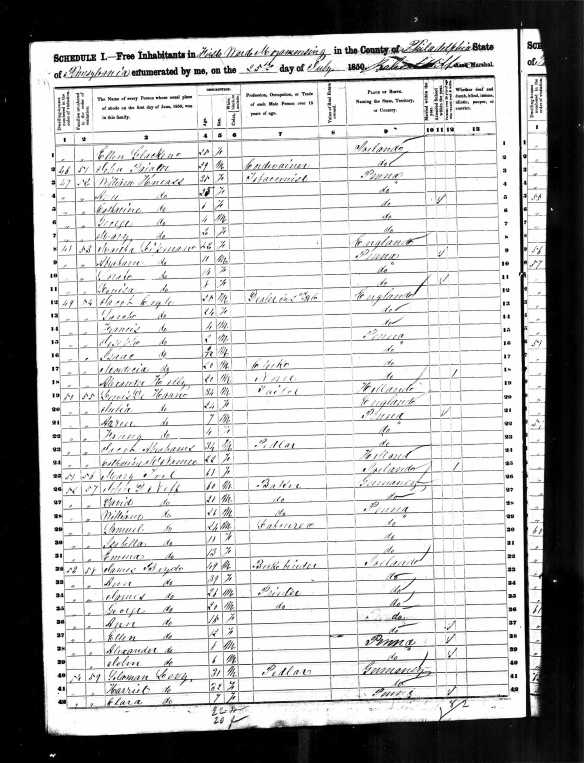

By 1851, the time of the second English census, my great-great grandfather Jacob Cohen had already moved with his family to Philadelphia. Much of the rest of his family of origin, however, was still in London. According to the 1851 census, Hart, my three-times great grandfather, was now a widower and 75 years old, living with two of his children, Elizabeth, now listed as 28 despite having been listed as 20 ten years earlier, and Jonas, who was 22. Jonas was not even listed as living with the family in 1841 when he would have been only 12 years old. All three were listed as general dealers and living at 55 Landers Buildings in Spitalfields parish in Tower Hamlets.

Although I thought this might indicate a move to a new neighborhood, my research revealed that Landers Buildings were on Middlesex Street, which was just one blog from New Goulston Street where the family had been living in 1841. The English genealogy site Genuki indicates that Spitalfields was a district within the parish of Whitechapel for at least some point in London’s history.

I do not know when Rachel, my three-times great grandmother died. My search of the BMDIndex, the English index of births, marriages and deaths that began to be registered in 1837, revealed quite a few Rachel Cohens who died between 1841 and 1851. I have ordered one certificate on a hunch that it might be the right one, but I need to do more investigating before I know for certain when she died.

Hart’s son, Moses, now 30 years old, had married Clara Michaels in the fall of 1843, according to the BMDIndex. I need to obtain a copy of the actual record to be sure, but on the 1851 census, Moses Cohen was married to a woman named Clara and had three daughters, Judith (6), Hannah (2), and Sophia (six months). He was employed as a general dealer and living at 35 Cobbs Yard in the parish of Christchurch in Tower Hamlets.

UPDATE: I now know that Moses in fact had left England with Jacob in 1848. This is not the correct Moses.

This neighborhood is about three miles west of where Moses had been living with his parents in 1841. Moses must have been fairly comfortable as they also had a servant living with them, although the Charles Booth Poverty Map depicted this area as poor in 1898.

The oldest son, Lewis, has been more difficult to track. He was not living with the family in 1841 nor was he living with his father and younger siblings in 1851. I would not even have known that he existed except for the fact that he appears on the 1860 US census reports living with his siblings Elizabeth and Jonas and his father Hart and on the 1880 census living with Elizabeth and Jonas. So where was he in 1841? 1851? According to those two US census reports, he was born in 1820, so would have been Hart and Rachel’s second child after Elizabeth. He might have been living independently in 1841, married, or perhaps just not home. The FamilySearch website indicates that the 1841 census had many holes; if someone was not staying at a home that night, they were not included in the census for that household. I found three Lewis Cohens on the 1841 Census, but none of them was a good fit. One was too old, one was living with different parents, and one was not born in England. But since the 1841 was the first true census taken in England, I assumed that perhaps Lewis was just not among those counted.

The 1851 English census did not provide any greater information on Lewis. There were several Lewis Cohens again, but only one who was a possible fit: he was born in Middlesex County in Spitalfields, Christchurch, around 1821 and was married to a woman named Sarah. They were living with Sarah’s mother, Ann Solomon.

I have found a marriage for this Lewis and Sarah in 1848 on the BMD Index and will write away for the record, but since Lewis was single in 1860 according to the US census, if this is the right Lewis, either Sarah had died or divorced him between 1851 and 1860. I searched for a death record for a Sarah Cohen who died between 1851 and 1860, and there were several on the BMD Index. I am not sure how to determine which ones might be relevant, but will order any that appear to be possibilities once I know that this was the correct Lewis.

UPDATE: I know now that Lewis had in fact emigrated from England to the US in 1846. This is not the correct Lewis.

The other possibility is that Lewis had immigrated to the US before the 1851 census or even the 1841 census. I cannot find him on either the 1840 or 1850 US census, but I did find some immigration records for a Lewis H. Cohen who was naturalized in Philadelphia in 1848.

Since Lewis is listed on the 1860 US census as Lewis H. Cohen, I am inclined to think that this is the right person. If so, then I also may have found a passenger ship manifest for Lewis, arriving in the US in 1846, which would have made him the first Cohen to immigrate to the US, not my great-great grandfather Jacob. I need to check further into this, but it seems quite possible that the reason Lewis is not on the 1851 census in England is that he was already in the US. But then why can’t I find him on the 1850 US census either?

The other mystery child of Hart and Rachel Cohen is the son identified on the 1841 census as John, the youngest child on that census whose age was given as 14, giving him a birth year of 1827. In my initial research on the family, I thought that John had become Alfred J. Cohen, who was also born in 1827. Alfred married Mary A. Cohen and remained in England where eventually they had seven children.

In reviewing my earlier work from last year, however, I am now doubtful that this was in fact the child of Hart and Rachel. Although I will order a marriage record for Alfred to be sure, I now think that the John in the 1841 census was actually Jonas, the youngest son of Hart and Rachel and the son who was living with Hart in 1851 in London and in 1860 in Philadelphia. My reasoning is that Jonas was not listed on the 1841 census when he would have been only twelve years old. Where else would he have been if not living with his parents? Also, since Jacob’s age was off by a few years on the 1841 census, it seems quite possible that there was an error in “John’s” age and also his name. Jonas is close enough to John, at least the first syllable, so a census taker might have just recorded it or heard it incorrectly. On the US census reports, Jonas’ age jumps around, making it difficult to pinpoint a correct year of birth. Although I am going to order whatever vital records I can for Alfred and for Jonas, right now my hunch is that Jonas and John were the same person, the youngest son of Hart and Rachel Cohen, born sometime between 1825 and 1830.

UPDATE: It seems quite clear to me now that “John” was Jonas.

So I have a lot of unanswered questions about my Cohen ancestors between 1841 and 1851. When did Rachel, my three-times great grandmother die? Where was Lewis in 1841? Did he marry in England? Did he in fact immigrate to the US in 1846? If so, why isn’t he on the 1850 US census? Are John and Jonas the same person, or were there in fact two sons younger than Jacob?

It will take some time to get the records that may help to answer these questions, so while I am waiting for those documents, I will move on to the next decade and the story of my Cohen ancestors in the United States.