Once again proving how valuable immigrants have been to this country, Clara Rothschild Katz’s two sons, Otto and Helmut (Harold or Hal) both did outstanding service for their new country against their old country during World War II. These memories of their service during the war were collected by Otto’s daughter and Hal’s niece, Judy Katz, and she generously shared them with me. All of the details below came from Judy’s interviews with her father Otto in 2001 and 2016 and with her uncle Hal in 2019 or from my Zoom calls with Hal and his family this year.

Otto did basic training in Vancouver, Washington, and went overseas in January 1944. He was in training in England until June 1944. Otto told Judy in his 2016 interview that he was first stationed in Bournemouth, England, and then was sent to Plymouth, where they took landing craft to Normandy, landing there two or three days after D-Day (or June 8-9, 1944). Otto described walking through the water to get to the beach, holding onto a rope that extended from the landing craft to the beach and holding his weapon overhead. One soldier in the group took his pants off; the rest got their wool pants wet and were extremely uncomfortable until their pants dried. Then they walked fifteen miles from the beach where they were loaded onto trucks and taken into France towards the front with Germany where they dug foxholes to sleep in. During that summer the Allied troops made substantial progress in moving the German army east out of France and into Germany.

In his 2019 interview with Judy, Hal reported that his brother Otto was in the Quartermaster Corps in the Third Army in France and Germany, commanded by General George Patton. Otto was in a unit stationed near General Patton’s headquarters as the troops battled into France and thus was near the center of the army’s advance through France into Germany. According to several sources, the quartermaster corps was generally in charge of procuring and delivering supplies for the combat units, including food, clothing, fuel, ammunition, and general supplies. They also planned for transportation and handle other logistical matters. And they could often be in danger during combat, serving alongside their fellow soldiers in providing those goods and services to them.

Otto reported that he saw little fire as they moved through France. By the fall of 1944, they were stationed for several months about fifty miles from Metz, France, and by early January, 1945, his division had advanced into Metz, which is about fifty miles from the German border.

They were in Metz until the spring, and Otto reported that the captain of their unit was Jewish and allowed the Jewish soldiers to stay for Passover in Metz. By that time (March 28, 1945) the rest of the unit had begun moving into Germany. They were all reunited in early April in Eisenach, Germany, which was close to the Nazi camp in Buchenwald.1 Otto told Judy in 2001 that the Jewish captain of their unit sent the known antisemites in the unit to Buchenwald, now liberated, to see the results of Nazi persecution, and the soldiers who visited came back very upset by what they had seen. Unfortunately, that did not erase their underlying antisemitism, according to Otto.

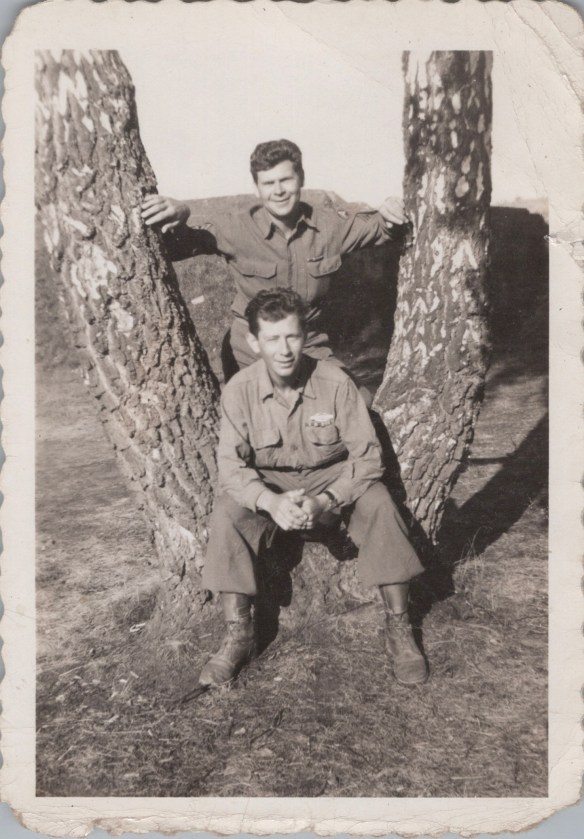

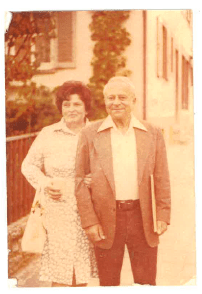

Otto’s unit stayed in Eisenach for two weeks. When the war ended on May 8, 1945, he was then stationed near Nuremberg. He was camped in Furth, near Zirndorf, where he and Hal were reunited for a brief visit. This photograph was taken during that visit in July, 1945.

Otto worked from March 1945 until August 1945 as a sewing machine operator, making snow suits and repairing army clothing. He was then transferred to Reims in France, and then Marseilles, where he waited to be sent to fight in the Pacific Theater. Fortunately, the war ended before he could be sent to the Pacific, and he was transferred to a suburb outside of Antwerp, where from August 1945 until November 1945, he was an inspector in a dry cleaning plant and was able to see Ruth and Jonas Tiefenbrunner. He returned home sometime after that and was discharged from the army on January 19, 1946.

Here is a map showing Otto’s path from Normandy to Metz to Eisenach to Zirndorf to Reims to Marseilles and finally to Antwerp.

Meanwhile, Hal also was stationed overseas during the war. He provided Judy with many details about his training and his service during her interview with him in 2019. He was drafted in September 1943 and reported for duty in New York, bringing nothing with him except some underwear and toilet articles. He told Judy that he “wasn’t smart enough to be nervous.” He was not yet nineteen years old at the time.

He was taken by train to Fort Dix in New Jersey and then to Camp Landing in Jacksonville, Florida, for basic training where he learned how to march in formation and how to handle an M1 rifle. He claimed he was terrible at shooting because he couldn’t see the target (Hal wore and wears glasses). He became a low speed radio operator and rifleman. While in Florida he applied for and became a US citizen.

Here is Hal with his rifle:

From Florida he was sent to Newport News, Virginia, and after one night there he boarded a Liberty ship with five hundred other GIs. The ship was not built for passengers, and the bunks were stacked four to five high in the cargo hold. They sailed to Naples, Italy—a trip that took 28 days. They were sent to a “Repo Depot,” a replacement depot where the newly arrived soldiers were used to replace those who had been wounded, killed, or captured. He spent two to three weeks there, waiting for assignments and marking time. They lived in tents and slept on cots, ten people to a tent.

Hal became a radio operator in the 88th Division, 351st Regiment, Second Battalion, Company B, in the Fifth Army in Italy. By that time Italy had surrendered to the Allies and had joined them in the war against Germany. The Allies were at the time of Hal’s service trying to drive the Germans out of Italy. His division was assigned to areas in Italy between Naples and Rome, and it was mostly quiet for the sixteen months he was there. In the spring of 1945, his regiment would move forward a couple of miles a day, occasionally having contact with the Germany army, and “sometimes people were shot.”

It was during this time that Hal did something extraordinary for which he received a Bronze Medal, an experience he did not even discuss in his interview with Judy and was reluctant to discuss with me. I will transcribe the citation given when he received medal.

Headquarters 88th Infantry Division

United States Army

APO 88

SUBJECT: Award of Bronze Medal

To: Private First Class Harold Katz, 42043105, Company F, 351st Infantry Regiment

CITATION

Harold Katz, 42043105, Private First Class, Company F, 351st Infantry Regiment. For heroic achievement in action on April 19, 1945 in the vicinity of San Giacomo di Martignone Italy. When his platoon was fired on from a house three hundred yard to its front, Private KATZ volunteered to go forward dodging from cover to cover until he was within seventy-five yard of the house and within easy calling distance. Then stepping boldly out into the open Private KATZ shouted to the enemy in perfect German that their force was completely surrounded and further resistance would be suicide. His answer was a blast of machine pistol fire from an upper window. Private KATZ was entirely alone and the nearest friendly troops were three hundred yards from the house, he kept his nerve and negotiated the surrender of forty-six Germans through sheer bluff, telling them that if anything happened to him the house and all its occupants would be completely destroyed. This plucky action of Private KATZ removed a serious obstacle to the advance of his battalion and permitted the advance to continue with almost no delay. This action is typical of Private KATZ’s courageous conduct in battle, and he reflects the fine traditions of the Armed Forces. Entered military service from New York, New York.

J.C. FRY, Colonel, Infantry, Commanding

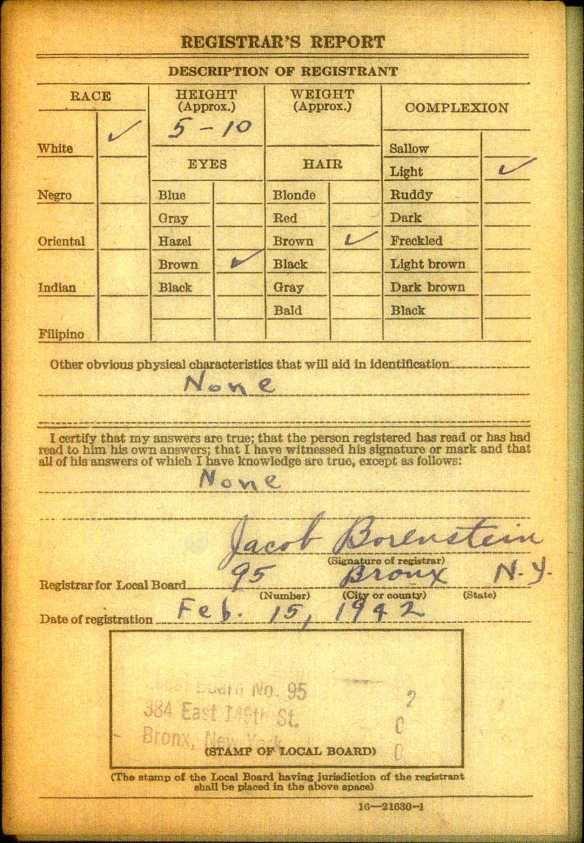

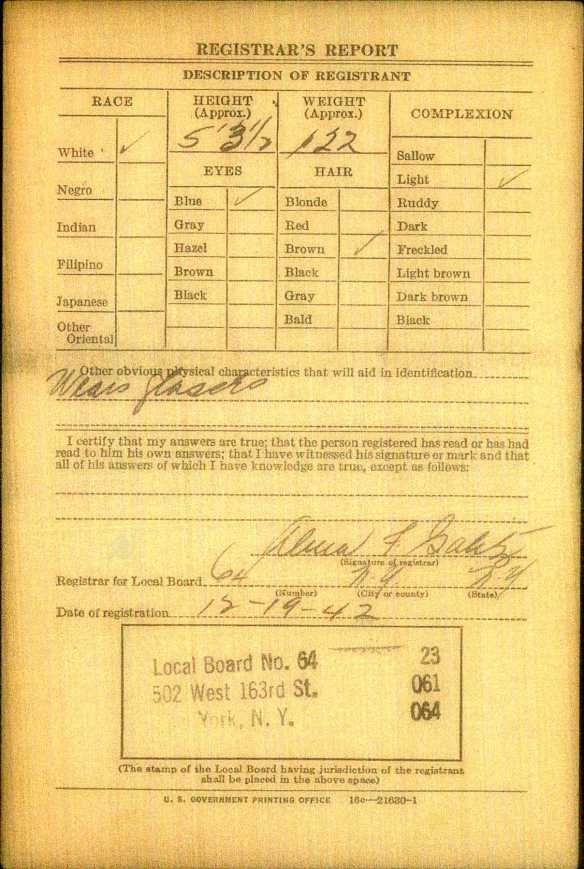

Imagine the scene. A house of Germans shooting at a company of American soldiers. Of the three hundred American GIs there, Hal Katz, all of 5’3 1/2” according to his draft registration, is the one to run up close to the house and yell, in German, that they were surrounded and had to surrender. And the Germans believed him and surrendered to him. I find it hard to imagine how he had the guts to do this.

Hal came home from Europe six months later in early September 1945 and was assigned to Fort Dix and then to Fort Wadsworth on Staten Island. He was able to sleep at home and report to duty at Fort Wadsworth during the day. He was finally discharged from the army on October 31, 1945. He had just turned 21.

As you can probably infer from these summaries of their interviews with Judy, both Otto and Hal spoke very modestly about their service during the war. Both of them played down the dangers they faced and the violence they must have seen. When I asked Hal on Zoom about his medal, he dismissed his heroic act as being just a stupid act by a very young man.

My cousins Otto Katz and Harold “Hal” Katz are two of the many men of the Greatest Generation who helped us defeat the Nazis: two young Jewish men, immigrants from Germany, who fought against Hitler and defended their new homeland here in the United States. We should all be eternally grateful to them.

- Eisenach was heavily bombed by the Allies during World War II and was taken over by the Americans in April 1945 near the end of the war. It then was taken over by the Soviets and became part of East Germany. See website at https://www.germansights.com/eisenach/#:~:text=Eisenach%20was%20bombed%20heavily%20at,miles%20away%20from%20the%20town). ↩