As reported previously, in 1841 Hart Cohen and his wife Rachel were living with four of their children, Elizabeth, Moses, Jacob and John, on New Goulston Street in the Whitechapel section of London, presumably part of the Chut community and living fairly comfortably with the two older sons working as china dealers. There was also at least one other son, an older son Lewis, and possibly another younger son, Jonas, although I am now thinking that John was in fact Jonas, but more on that later. By 1860, only Moses (and John if there was in fact a son named John) was living in England; all the rest were in Philadelphia. I will try to trace in chronological order the major events and moves made by these family members.

In order to get a complete picture of the family and their lives in England, I will need to get copies of the vital records, including their birth certificates and marriage certificates. I am now trying to learn how to do that. I have received some extremely helpful tips and information from another of my favorite genealogy bloggers, Alex Cleverley of the blog Root to Tip. Alex is a very experienced English genealogist, and with the help she has given me, I will now order the records I need. Unfortunately it appears that there is no fast and easy access to these documents so for now I will have to rely on the 1851 census, a few other secondary sources, and later census reports and infer a number of facts from those documents. As I receive other documentation, I will report what I find.

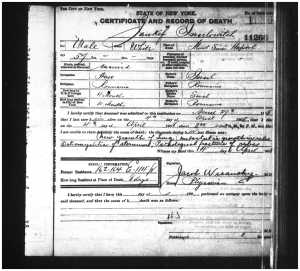

I will start with Hart and Rachel’s son Jacob because he is my direct ancestor, my great-great grandfather, and thus the one I have the greatest interest in tracking. According to the 1841 census, Jacob was 15 that year, giving him a birth year of 1826.

This appears, however, to be inaccurate based on later census reports from the United States and from a passenger manifest, all of which indicate a birth year of 1824 or 1825. That would have made Jacob 16 or 17 in 1841.

This also seems more consistent with the fact that Jacob may have married his wife Rachel Jacobs (possibly a relative of his mother, whose birth name was also Jacobs) on October 24, 1844. Without an actual marriage certificate I cannot be completely sure, but I found a marriage record on SynagogueScribes for Jacob Cohen, son of Naphtali Hirts HaCohen, to Sarah Jacobs, at the Great Synagogue of London on that date. The Hebrew name is not identical to what I had earlier found for Hart, Jacob’s father, but it is very close. I know that Sarah’s maiden name was Jacobs based on the death certificates of two of their children, Isaac and Frances. Thus, I feel fairly confident that this is in fact their marriage record as transcribed by SynagogueScribes.

| COHEN | |

| Forenames | Jacob |

|---|---|

| Hebrew Name | Jacob |

| Event | Marriage |

|---|---|

| Date | 1844 [29 Oct] |

| Occupation | |

| Address |

| Father | |

|---|---|

| Father’s Hebrew Name | Naphtali Hirts HaCohen |

| Mother’s Family Name | |

| Mother’s Forename | |

| Mother’s Hebrew Name |

| Spouse | JACOBS Sarah |

|---|

Frances, or Fanny, was Jacob and Sarah’s first child, born around 1847, as inferred from later US census reports. Within a year of Fanny’s birth, Jacob and Sarah left London and moved to Philadelphia. On July 7, 1848, Jacob, Sarah and Fanny, an infant, arrived in New York aboard the ship New York Packing. Jacob’s age was given as 24, consistent with a birth year of 1824, and Sarah was 20, giving her a birth year of 1828. Jacob’s occupation was given as “General dealer,” as were many other men on the manifest.

Jacob was the first of Hart and Rachel’s children to leave London and move to the US. His siblings and eventually his father began arriving several years later. I found this interesting, given that Jacob was not the oldest son, but the fourth child and third son. Why did he go first? What drew him away from his family and to America with his young wife and baby? I also found it revealing about my direct line that both Hart and Jacob were the sons who left their families behind and moved to a foreign country. As far as I can tell, Hart arrived alone and without his family when he immigrated to England, just as his son Jacob did fifty years later when he left England and moved to the US. I can’t say I inherited this willingness to take risks and move far from home, having never lived more than four hours from where I was born, but I like the idea that my ancestors were such risk-takers and so independent.

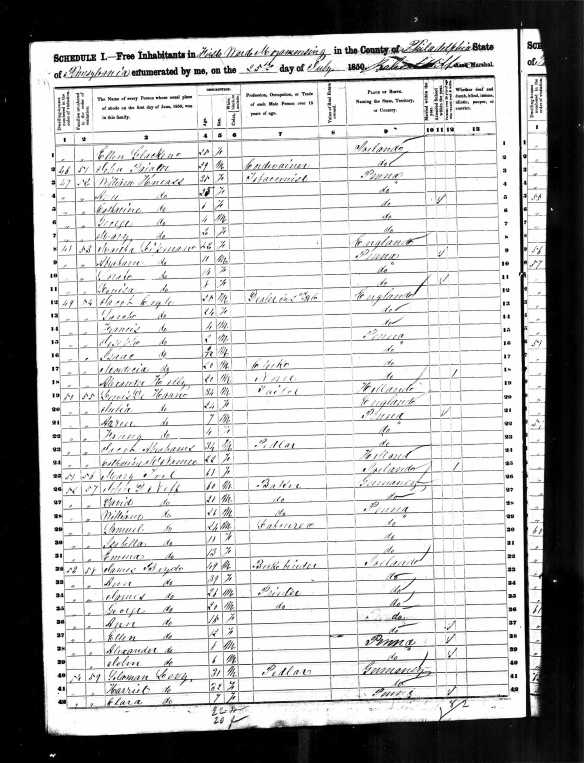

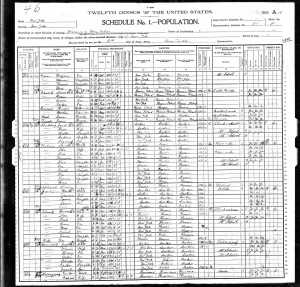

I don’t know whether Jacob and his family stayed very long in New York after arrival, but by 1850, Jacob and Sarah were living in Philadelphia. It was not easy finding Jacob and Sarah on the 1850 US census. I tried searching for all Jacob Cohens, Sarah Cohens, Fanny Cohens, and variations on each name and wild card searches on each name, but came up empty for a family that fit my relatives. Then I decided to search just by first names for a Jacob with a wife named Sarah and a daughter Fanny and found them listed as “Coyle,” not “Cohen,” another instance of a mistaken name on a census report. I am quite certain that these are my relatives despite the Irish surname because all the other facts fit closely enough—names, ages, places of birth for Jacob, Sarah and Francis. Jacob’s occupation is described as “Dealer in 2d HG,” which I interpret to mean a dealer in second hand goods. The only inconsistency is that Francis is listed as male, not female, but later census reports correct that mistake and list her as female.

By 1850, Jacob and Sarah had two additional children born in Pennsylvania. Joseph was two years old, so presumably born shortly after Jacob and Sarah had arrived in the US in 1848, meaning Sarah was pregnant when they left England. Isaac was six months old, so presumably born in January, 1850, since the 1850 census was dated July 25, 1850.

There were also two other men living in the household, both twenty years old: Mordecia (Mordecai?) Coyle (Cohen?) and Alexander Kelly. Unfortunately, the1850 census did not identify the relationship of each individual to the head of household as later census reports did, so I do not know who these two men were. Mordecai might very well have been a relative since he shared the same surname with the family. But how might he have been related? None of Jacob’s siblings were old enough to have had a twenty year old son, and Jacob did not have a younger brother named Mordecai. Also, the census indicates that Mordecai was born in Pennsylvania, meaning that his parents would have been in the US in 1830. Perhaps Hart had a brother who had emigrated from Holland or Amsterdam or England that early? Or was Mordecai not even related to Jacob? I have done some preliminary searching for other records for Mordecai, but so far have not had any success.

Thus, by 1850 my great-great grandfather was settled in Philadelphia, a young man with a young wife and three little children, working as a dealer in second hand goods. His parents and his siblings were all still back in London, but between 1850 and 1860, that would change, and Jacob’s family both in his household and in Philadelphia would expandd many times over.

My next post will describe what the rest of Hart’s family was doing between 1841 and 1860, by which time most of the Cohens had arrived in Philadelphia.

Related articles