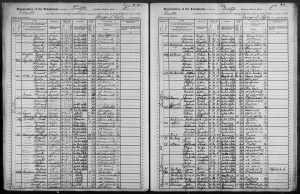

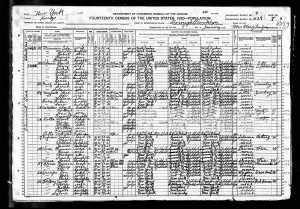

In my last two posts, I wrote about the vast emigration of Jews from Romania between the late nineteenth century and World War I in the face of widespread anti-Semitism and poverty. According to one source, almost thirty percent of Romanian Jews migrated to the United States or Canada between 1871 and 1914; many others migrated to what was then Palestine.[1] Wikipedia estimates that about 70,000 Jews emigrated from Romania, almost a quarter of the total Romanian Jewish population in that period.

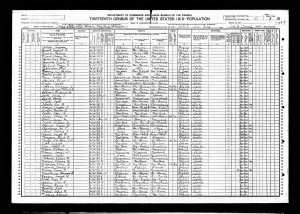

Many of those who left were part of the Fusgeyer movement, groups who walked from their home towns across Romania to escape, often depending on donations raised by entertaining the crowds in towns throughout their route to freedom. My grandfather was one of these walkers, and so perhaps were his siblings, cousins and other family members, though I’ve not heard any other descendant report that their grandparent walked across Romania. According to Culiner, there are no statistics on how many people were a part of this movement or how long it lasted. Groups ranged in size from forty people to 300 people, and in 1903 about 200 to 300 Jews were leaving Romania each week, many on foot. (Culiner, p. 20).

Although Jacob Finkelstein’s report of the experiences of his 1900 Fusgeyer group painted a generally rosy picture of their trek, being welcomed and well-fed in most places they visited, other groups faced greater struggles. One observer reported that he saw groups where people were famished, in some cases starving, and living in horrible conditions. He wrote:

One has to imagine 300 people, men, women and children wandering through the cemetery [where they were then living] like famished wolves, burnt by the sun during the day, tormented by mosquitoes in the night, all three hundred of them with bare feet, sick, some moaning, others crying: fever-racked women who are incapable of feeding their young, the children pale and suffering.[2]

Is it any wonder that my grandfather never talked about his life in Romania, other than to mention the music and beautiful horses he remembered? I’ve asked many of my newly-found Rosenzweig and Goldschlager cousins if they knew anything about their ancestors’ lives in the “old country,” and the response I’ve heard over and over is that their grandparent never wanted to talk about those days, but wanted to focus on the present and the future. Given the conditions they endured both living in Romania and leaving it, why would they want to remember any of it?

Despite this large-scale emigration of Jews before World War I, there were close to 800,000 Jews remaining in Romania at the end of that war. (This large increase resulted from the addition of Bukovina, Transylvania, and Bessarabia to the territory controlled by Romania in accordance with the terms of the 1919 Paris Peace Conference after World War I.)

By the end of World War II, that community had been further decimated. Approximately 300,000 Jews were murdered in the Holocaust between 1941 and 1944 by the Romanian government, the largest number of people killed by any Nazi ally other than Germany itself. Nevertheless, unlike in many other countries in Europe, the majority of the Jews in Romania survived the war. Estimates vary, but approximately 300,000 Romanian Jews survived. Most, however, did not return to or remain very long in Romania. The Communist era resulted in further reduction of the Jewish population with many who had returned emigrating to Israel or the United States or elsewhere. Wikipedia includes this chart of the declining population of Jews in Romania:

| Historical population | ||

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1866 | 134,168 | — |

| 1887 | 300,000 | +123.6% |

| 1899 | 256,588 | −14.5% |

| 1930 | 728,115 | +183.8% |

| 1956 | 146,264 | −79.9% |

| 1966 | 42,888 | −70.7% |

| 1977 | 24,667 | −42.5% |

| 1992 | 8,955 | −63.7% |

| 2002 | 5,785 | −35.4% |

| 2011 | 3,271 | −43.5% |

| Censuses in 1948, 1956, 1966, 1977, 1992, 2002 and 2011 covered Romania’s present-day territory Source: Demographic history of Romania |

||

These facts are important in order to put into context my next post: what Romania is like today, as seen through Jill Culiner’s eyes in her book Finding Home and through Stuart Tower’s eyes as depicted in his photographs of Romania.

[1] Joseph Kissman, “The Immigration of Romanian Jews Up to 1914,” YIVO Annual of Jewish Social Science (New York 1947-1948), p. 165, as cited in Jill Culiner, Finding Home: In the Footsteps of the Jewish Fusgeyers (Sumach Press 2004), p. 19.

[2] Isaac Astruc, “Israelites de Roumanie,” p. 43, as translated by and quoted by Culiner, p. 23.