While you all may have thought that for the last several months I was obsessed with Nusbaums and Dreyfusses (and I guess I was), there were several other things happening in my genealogy life (not to mention my actual life) that I haven’t had a chance to blog about yet. One of the biggest things was the discovery of documents and information about another line of my family, the Schoenfelds, and another ancestral town, Erbes-Budesheim.

Who are the Schoenfelds? Moritz Seligmann, my 3-x great-grandfather from Gau Algesheim, married two Schoenfeld sisters (not at the same time, of course). First, he married Eva Schoenfeld and had four children with her, and then he married her younger sister, Babetta, my 3-x great-grandmother, the mother of Bernard Seligman, my great-great-grandfather. Moritz and Babetta had seven children together in addition to the four born to Eva.

Because the birth names of women often disappear, it is all too easy to overlook the family names and lines that end when a woman changes her name to that of her husband. Although I was always aware of the family names of Goldschlager, Brotman, Cohen, Nusbaum, and Seligman (as well as those from my paternal grandmother’s side, not yet covered on the blog), I had no awareness of a family connection to the names Rosenzweig, Dreyfuss, Jacobs, and Schoenfeld. Discovering the Schoenfeld name, like discovering those others, was an exciting revelation and addition to my extended family tree.

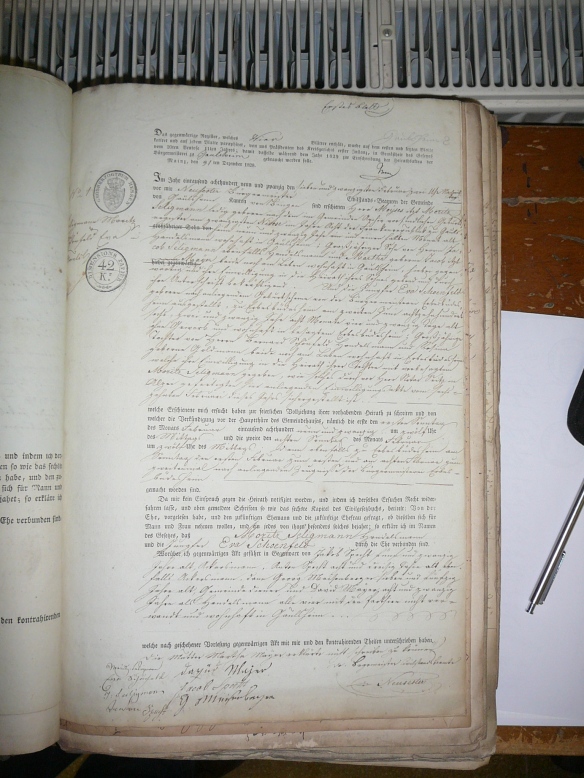

So how did this happen? As I wrote back on December 1, Ludwig Hellriegel’s book about the Jews of Gau Algesheim revealed that Moritz Seligmann was born in Gaulsheim and had moved to Gau Algesheim as an adult. That discovery had led me to the Arbeitskreis Jüdisches Bingen and a woman named Beate Goetz. Beate sent me the marriage record for Moritz Seligmann and Eva Schoenfeld, which revealed that Eva was the daughter of Bernhard Schoenfeld and Rosina Goldmann from Erbes-Budesheim. (Now I also know another maternal name—Goldmann.)

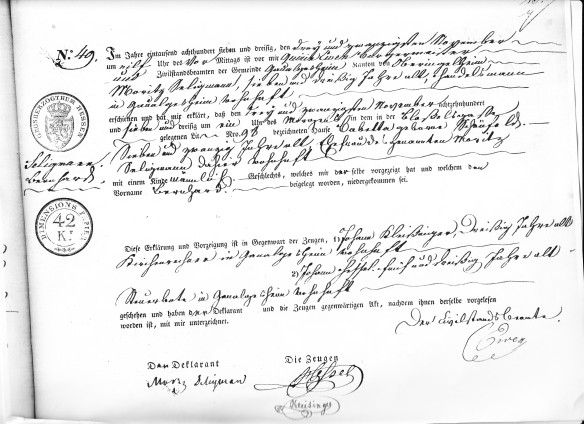

From there I contacted the registry in Erbes-Budesheim to ask about records for my Schoenfeld ancestors, and within a short period of time, I received several emails from a man named Gerd Braun with an incredible treasure trove of information and records about my Schoenfeld ancestors.

But first, a little about Erbes-Budesheim. Erbes-Budseheim is a municipality in the Alzey-Worms district of the Rhineland-Palatine state in Germany. It is located about 25 miles south of Gaulsheim where Moritz Seligmann was born and grew up and about 27 miles south of Gau Algesheim where Moritz and his family eventually settled. The closest major city is Frankfort, about 46 miles away.

The town has an ancient history, dating back to the Stone Age, according to Wikipedia. Like many regions in Germany, it was subject to various wars and conquerors throughout much of its history. During the Napoleonic era in the late 18th, early 19th century, Erbes-Budesheim and the entire Alzey region were annexed as part of France; after 1815 it was under the control of the Grand Duchy of Hesse.

Although originally a Catholic community, after the Reformation Erbes-Budesheim became a predominantly Protestant community. Some sources say that there was a small Jewish community in Erbes-Budesheim as early as the 16th century, but as of 1701, there were only 15 Jews (two families) living in the town. A third family lived there in 1733, but even as late as 1824 and throughout the entire 19th century, the population did not exceed 23 people. The Jews in Erbes-Budesheim for much of that history joined with Jews from neighboring communities for prayer, education, and burial.

By 1849, however, one Jewish resident named Strauss had dedicated the first floor of his home for prayer services, and it was furnished with the essential elements for a synagogue: Torah scrolls, an ark, a yad, and a shofar, for example. Perhaps this is where my 4-x great-grandfather Bernhard Schoenfeld went to daven [pray] when he and his family lived in Erbes-Budesheim.

Strauss home where the Erbes-Budesheim Synagogue was located

http://www.alemannia-judaica.de/erbes_buedesheim_synagoge.htm

There is also a Jewish cemetery in Erbes-Budesheim.

Erbes-Budesheim cemetery http://www.alemannia-judaica.de/images/Images%2059/ErbesBuedesheim%20Friedhof%20102.jpg

On this video you can some headstones with the name Schoenfeld from the Erbes-Budesheim cemetery.

By 1939, there were only eight Jews left in the town, and it would appear from the allemannia-judaica website that none of these survived the Holocaust.

Thus, Erbes-Budesheim was never a place where a substantial Jewish community existed, and it makes me wonder what would have brought my ancestors there. Why would anyone want to be one of a handful of Jews in a community? In my next post, I will consider that question and share the documents I received from Erbes-Budesheim.