My last post told the tragic story of Emil-Jacob Seligmann, Jr., the great-grandson of my three-times great-grandfather Moritz Seligmann. This post will tell the story of his sister, Christine, known by the family as Christel. Emil, Jr. and Christel were the children of Emil Seligmann, Sr., who was Jewish, and Anna Maria Angelika Illian, who was Catholic, and they were raised as Catholics. But, as we saw in the prior post, Nazis treated those who had two Jewish grandparents as Mischlings in the First Degree. Although they were not thus identified as wholly Jewish, they were nevertheless not Aryan either and, as we saw with Emil, often persecuted. Emil was sent to Buchenwald in August 1944 and died there six months later on February 14, 1945, from poor health and a heart attack.

Christel was not sent to a concentration camp, but she faced persecution as well. In going through various papers that were found in Christel’s apartment after she died in 1982, my cousin Wolfgang located documents that revealed that Christel had applied for reparations from the German government for the harm and losses she suffered during the Nazi era. Those documents (which he has shared with me) reveal what Christel experienced and endured at the hands of the Nazis. The documents are all in German, but with a lot of help from Wolfgang and my elementary understanding of German, I have been able to piece together Christel’s story. You can see the documents I received here: Christine Seligmann dox

The first document was written by Christel on January 3, 1947, outlining her life in Wiesbaden before and during the Nazi era and World War II. She wrote that she was born on July 30, 1903 in Erbach, Germany. Her parents were quite wealthy, so Christel did not need to work. But in 1933 she became a certified baby nurse and began working for mostly Jewish families in that capacity. She was out of work due to poor health (rheumatism) from 1938 to 1942, but in 1942 returned to work for various families.

After losing both of her parents in 1942, Christel stopped working as a baby nurse and instead made a living by renting rooms in her family home. But in August 1944, her situation became much worse. Her brother Emil was arrested and sent to Buchenwald, where he died six months later.

Wolfgang found among Christel’s papers two cards that she received from her brother Emil while he was at Buchenwald. Wolfgang translated and summarized these cards for me.

The first card is dated September 10, 1944. At the top of the page are pre-printed instructions regarding written communications to and from prisoners. Prisoners were allowed to send and receive just two letters a month. The letters had to be written clearly. The rules also state that prisoners were allowed to receive food.

In the body of his message, Emil informed Christel that he was living at Buchenwald and that he was doing well, but he made several requests that he considered urgent. He asked her to send him money (30 Reichsmarken) and a long list of food items: marmalade, canned blackberries and raspberries, sugar, salt, cigarettes, and some cutlery. He also asked for something to treat fleas. He thanked her several times.

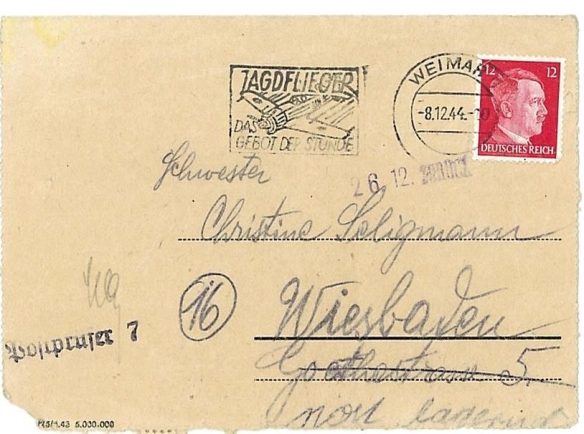

His second letter sounded more desperate. It was written in December, 1944, and it is obvious that the conditions and weather had become worse since his first card two months earlier. We can’t tell whether the siblings had exchanged other letters between September and December, but from the content of Emil’s December letter, we know that Christel had at least sent him one package. He wrote that he was happy to have received the package from her because he had been very worried and was glad to know that she was alive. He asked her to write him a letter—so perhaps she had not written to him, just sent the package.

He said that everything in that package was perfect, but that he now needed more money (50 Reichsmarken) and some winter clothing—gloves, earflaps (like ear muffs, I assume), and a winter jacket. He also asked for towels, handkerchiefs, a pen, a spoon, salt, cigarettes, glasses, and marmalade. Emil acknowledged that Christel might be too busy with work to get the items to him quickly and said she should ask the other women in her house for help. He closed by wishing her a good Christmas and sending her kisses.

We don’t know whether Emil heard from Christel again or whether she heard from him. He died less than two months after Christmas on February 14, 1945.

Meanwhile, Christel was having her own problems with the Nazis. On the same day that Emil was arrested in August, 1944, the Gestapo raided their family’s apartment and forced her to move out on one day’s notice at great cost and with no help. They told her that if her furniture was not removed by the next morning, she would find it on the street. She was able to salvage some, but not all, of her belongings.

From October 1944 until December 1944, she was able to work as a nanny for a Christian woman, but then the Gestapo forced her to take a job in a cardboard factory. She found this work very difficult, and the long walk back and forth every day made matters even worse. Her feet became frostbitten and she developed bladder problems, but despite consulting three different doctors, she was unable to get any of them to give her a medical note to excuse her from work.

Once the war ended and the US army occupied Wiesbaden, Christel’s home was returned to her, but then was soon taken back by the US army to use as living quarters for American soldiers. Christel had just one room to live in. Nine months later her home was returned to her.

Christel filed a claim for reparations from the German government in November, 1953, for the loss of income and value she suffered by being forced from her home by the Gestapo, for the loss of her profession, for the damage to her health, and for the insults and humiliation she endured. She also claimed that a possible marriage was thwarted by the laws imposed by the Nazis. Wolfgang located in Christel’s papers a five-page petition filed by her attorney, Georg Marx, detailing her claims. Unfortunately, the copy I received is a bit too blurry (making it even more difficult to translate the German), but Wolfgang told me that it reiterates much of what Christel herself wrote in 1947 but with more details about her medical ailments.

According to Wolfgang, Christel did receive some money for reparations, but not very much. She continued to live in her apartment in Wiesbaden for the rest of her life. When she died in 1982, Wolfgang and his father and uncle cleaned out the apartment. Christel was a bit of a hoarder, and there were many, many papers that were simply thrown away, papers that today might tell more of her story and that of her family.

Fortunately, however, Wolfgang’s uncle Herbert saved the “magic suitcase” that was in Christel’s apartment and that has become so critical to the family research that Wolfgang and his mother have done and have shared with me.

The small compensation Christine Seligman received for the hardships and harassments in the Nazi era indicates to me the extent of the incredible and horrible experiences of all the other individuals who were treated much worse than Christel.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, her situation doesn’t compare to that of others. But it was still very difficult for her.

LikeLike

Reading her story, I was thinking about the fact she lost her brother as well and that alone must have taken quite a tremendous toll on her. Once again having these documents are truly a blessing in so many ways.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, these documents preserve her story, which otherwise would have been lost to history forever. Thanks, Sharon.

LikeLike

Hoping the “magic suitcase” contained all of the important papers and those which were thrown away were of little value. It was sad to read the list of things Emil had to do without. It’s good to know Christel was able to keep the family apartment but she still must have had a hard time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The suitcase certainly contains many important family history documents, and I am grateful for that. We will never know what else there was. The fact that Christel was a hoarder is probably one sign of how she continued to suffer for the rest of her life. When you’ve lost so much, it makes sense that you would hold on to everything you do have.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Could it be that the Doctor who refused to provide an absence note was a Nazi? Since Christal suffered from rheumatism in the past the symptoms must have been clear when she sought medical help and a doctor’s note to be excused from work. The Nazis were out to eradicate the Jewish people and anyone who carried a part of Jewish heritage. This part of the story brings it to mind for me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t know if the doctors were Nazis or just afraid of being punished if they dared to protect someone with Jewish family. Thanks, Emily.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I lnow that is a question no one today can answer. Your reply is a better one than mine. You ate correct. Fear could have been at the root of why the doctor would not help.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And that’s what worries me about today’s world. Too many people are either afraid to speak up against injustice or are just indifferent.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Christel’s story is so sad, and I too can see why she would become a hoarder later in life. It’s also an important story, because I think there is a public perception that if people weren’t actually taken to concentration camps, then they were “ok”, when obviously that is far from true.

Thank you Amy, (and Wolfgang) for telling her story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are so, so right, Su. Sometimes people only (ONLY??) consider the six million who were killed, not all those who survived, but suffered terribly and bore those scars for the rest of their lives.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It doesn’t help that popular culture tends to only tell the sensational stories (and often so so badly) — both in “the news” and in film/novels, etc. With contemporary events, once the news machine has packed up and decided to move on to the next “story”, the world is able to forget the on-going, day to day suffering.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes. For example, people here have moved on from the two mass shootings just a couple of weeks ago.

LikeLiked by 1 person

😦 … and here, those who survived the mosque shootings in March are struggling to get any help (and access to some of the huge amount of money that was donated), partly because the news caravan has moved on.

LikeLiked by 1 person

At least your government did something to limit access to guns afterward.

LikeLiked by 1 person

They have tried. Turns out we have a gun lobby here too ☹️

LikeLiked by 1 person

GRRRR…

LikeLiked by 1 person

My feeling too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just wanna tell you, that the book by Thomas Harding is very interesting. I’m on page 101 and hope to have read it by the end of the week.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am so glad that you are finding the book worthwhile. I felt like I learned a lot about modern German history from reading it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Everyone learns from it.

I now know a bit about our history (began some 4 years ago with it) and the various single steps it took to terrorize this country at last.

Every now and then I read about the crimes against humanity back then, it makes you feel terrible, to say at least.

What I learn from it: No one can predict that mankind learns friom these desasters. Some scenes nowadays look familiar to us.

As for me it seems we all have to go through these desasters again and again before, maybe, all that comes to a rest.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, we seem not to learn from history. But maybe if enough people have learned from history and are brave enough to speak out, we can prevent such horrors from happening again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was reminded of my parents and mother-in-law who were not necessarily hoarders but they had trouble throwing anything out – good for a genealogist but not so good for the children who have to clean out the house. I always thought it was due to the depression and that they never wanted to be caught “without”. My mother must have had 20 bottles of salad dressing, all stored on a shelf in the laundry room she couldn’t even reach.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That does sound like Depression mentality. In Christine’s case I do wonder if it was the fear of having thing and people taken from her again.

LikeLike

I read this the other day on my iPad and couldn’t comment. I meant to come back and comment and now here I am on my iPad again. So I am going to let Siri help me. I wish more stories like Christine’s were available in the form of memoir available to older children. We have quite a few good memoirs of survivors who were in hiding like Joanna Reiss and Those like Anne Frank who did not survive. But we don’t have too many stories for kids of people who had to live in the cracks between acceptance and certain death. Not sure I am making any sound. Maybe that’s another book you can write. It wouldn’t be a memoir but it could be a hybrid fiction nonfiction.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Siri changed sense to sound. She is not my friend.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I never use Siri to dictate. Just to ask questions that she never can answer. Google is much better.

LikeLike

It’s true—most Holocaust stories involve the camps. But there were many, many people who suffered in other ways and whose stories are not told. I never knew how children of mixed marriages were treated until I found them in my family tree.

Why can’t you comment on your iPad?

LikeLike

Another sad story, and one that highlights the loss the survivors felt and how nothing could ever really adequately compensate for the kinds of treatment and atrocities and loss of all kinds that was endured by the Jewish people – not to mention the other groups of people targeted by the Nazis. Truly terrible.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, Christel never recovered. Her hoarding was clearly a sign of her fear of further losses.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Escaping from Germany, Part IV: Helene and Martha Loewenthal, An Unfinished Research Project | Brotmanblog: A Family Journey

Pingback: Friday’s Family History Finds | Empty Branches on the Family Tree