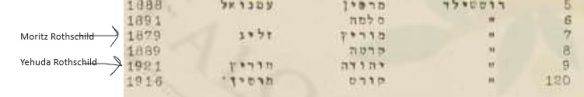

Levi Rothschild’s fourth child, Hirsch (also known as Harry) and his three children Gertrude, Edith, and Edmund all managed to leave Germany in time to survive the Holocaust. His wife and their mother Mathilde Rosenbaum, however, did not.

Gertrude, Hirsch’s oldest child, was the first member of the family to come to the US although her husband preceded her. She had married Gustav Rosbasch sometime before 1933, the year their first child was born. Gustav was born in Kremenchug, Russia (maybe now Ukraine?) on August 12, 1901. Gustav, a surgeon, came to the US on October 10, 1934, listing his last residence as Delmenhorst, Germany, a town in the Saxony state of Germany. He reported his wife Gertrude as the person he had left behind in Delmenhorst, and his uncle Phillip Rosbasch of Rochester, New York, as the person he was going to in the US. 1

Gertrude arrived almost a year later with their two-year-old daughter. They arrived on September 8, 1935, listing their prior residence as Delmenhorst and listing “G. Rosbasch” in Rochester as the person they were going to; “H. Rothschild,” Gertrud’s father, was listed as the person they had left behind in Delmenhorst.2 Gustav and Gertrude had a second child in Rochester a few years after Gertrude’s arrival.

The next member of the family to escape to the US was Edith, Gertrude’s younger sister. She arrived in New York on May 28, 1937, listing her destination as Rochester, New York, where her sister Gertrude was living, and listing her father, “Dr. Rothschild” as the person she’d left behind in Delmenhorst, her prior residence.3

Edith and Gertrud’s brother Edmund arrived a year after Edith on June 24, 1938, in New York with his destination being New York City where his uncle Karl Rosenbaum, his mother’s brother, was living. Edmund identified his occupation as a physician, like his father and his brother-in-law Gustav, and listed his father “Dr. Harry Rothschild” of Delmenhorst as the person he left behind, but Edmund gave his last residence as Basel, Switzerland, not Delmenhorst.4

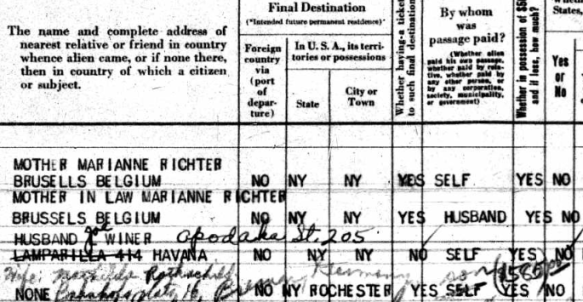

Thus, the three children of Hirsch and Mathilde Rothschild had all arrived before Kristallnacht in November 1938. Their father Hirsch did not arrive for over another year. His ship sailed from Havana, Cuba, and arrived in Miami on December 17, 1939, three months after World War II had begun. Hirsch listed his occupation as a physician and the person he was going to as his son “Edw. Rothschild” in Rochester, New York. He also listed his last residence as Delmenhorst.

Hirsch Rothschild passenger manifest, The National Archives At Washington, D.c.; Washington, D.c.; Series Title: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving At Miami, Florida; NAI Number: 2788508; Record Group Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787 – 2004; Record Group Number: 85, Roll Number: 086, Ancestry.com. Florida, U.S., Arriving and Departing Passenger and Crew Lists, 1898-1963

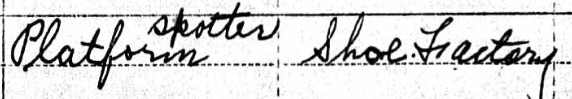

There is a notation on Hirsch’s line on the passenger manifest that reads, “Admitted on appeal 1-3-40.” Also for the section listing the person left behind in the prior country, where the word None had been typed, someone added in handwriting, “Wife Mathilde Rothschild” living in Bremen, Germany. Another handwritten change indicates that his son had paid his passage; “self” was crossed out.

Were these additions of Mathilde’s name and the fact that his son was paying his way what helped Hirsch win his appeal? Why wouldn’t he have listed Mathilde before? Why was she living in Bremen, not Delmenhorst? When did Hirsch actually leave for Germany? How long had he been in Cuba before sailing from Havana to Miami in December 1939?

These are questions for which I currently do not have answers, just some speculation. Was Mathilde ill and hospitalized in Bremen? Is that why she hadn’t come with Hirsch to the US?

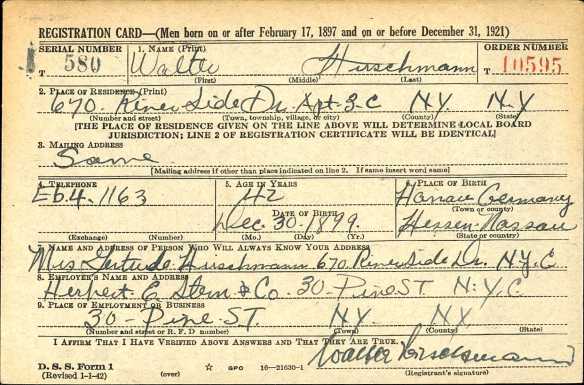

I don’t know, but we do know that by early 1940, Hirsch and his three children and his son-in-law and granddaughter were all safely in the US. Gustav and Gertrude and their two children were living in Rochester, New York, where Gustav was a doctor.5 Edith was also in Rochester, working as a housekeeper for another family.6 Edmund was working as a doctor at the Monroe County (New York) Infirmary and Home for the Aged in Brighton, New York, only four miles from Rochester.7 I could not locate Hirsch/Harry on the 1940 US census, but on April 25, 1942, when he registered for the World War II draft, he was at that time living in Rochester with Gertrude and Gustav and unemployed.

Harry Hirsch Rothschild, World War II draft registraiton, The National Archives At St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; World War Ii Draft Cards (Fourth Registration) For the State of New York; Record Group Title: Records of the Selective Service System; Record Group Number: 147; Box or Roll Number: 522, Name Range: Rosser, Roscoe – Rought, Walter, Ancestry.com. U.S., World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942

But not long after that Hirsch/Harry must have moved to New Rochelle, New York, 350 miles from his children in Rochester, where he found work as the house physician for the Jewish Home for the Aged in New Rochelle. Harry died on April 18, 1945, in New Rochelle; he was 64. Heartbreakingly, his obituary revealed that as of that date with Germany’s surrender just a few weeks away, Harry and his children did not yet know what had happened to Mathilde, their wife and mother. The obituary states that Harry’s wife Mathilde “remained in Germany when Dr. Rothschild left the country. Relatives here have been trying through the Red Cross to learn her fate.”

Yad Vashem, however, reveals what had happened to Mathilde. On November 18, 1941, she had been deported to the Minsk ghetto in Belarus where she was murdered on July 28, 1942. She was 57 years old. It must have been devastating for the family to learn this.8

But Mathilde and Harry were survived by all three of their children and by their grandchildren. Their daughter Gertrude and her husband Gustav remained in Rochester, New York, for the rest of their lives, where Gustav continued to practice medicine. He died on January 7, 1992, at the age of 90.9 Gertrude outlived him by five and a half years; she died on July 4, 1997; she was 86 years old.10 They were survived by their children and grandchildren.

Gertrud’s sister Edith married Abram Solomon (Jalomek) in 1943.11 As far as I can tell, they did not have children as none are listed in either of their obituaries. Edith died July 28, 2003, in Rochester, at the age of 92;12 her husband Abram died many years before on June 9, 1971, in Rochester.13

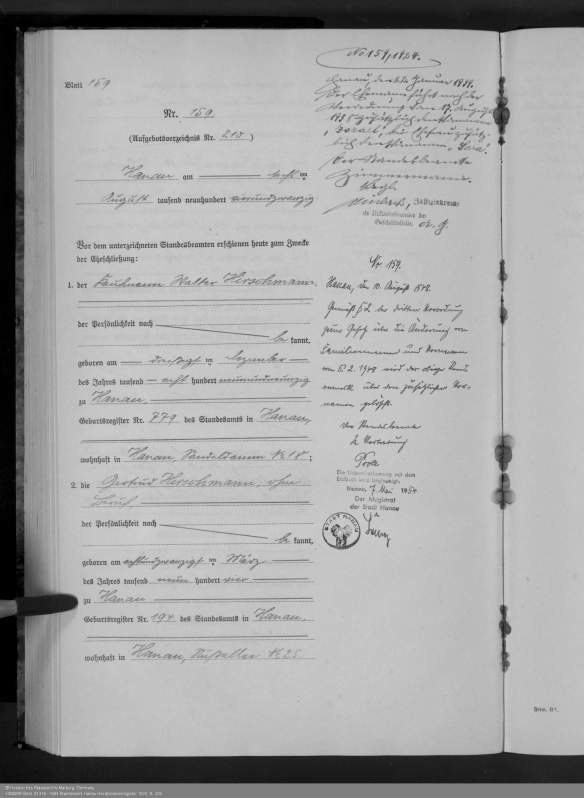

Edmund Rothschild, the youngest child of Hirsch and Mathilde, had registered for the draft on October 16, 1940.

Edmund Rothschild, World War II draft registration, National Archives at St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; Wwii Draft Registration Cards For New York State, 10/16/1940 – 03/31/1947; Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147, Name Range: Roth, Cletus-Rotonde, Nicholas

Ancestry.com. U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947

He married Helene Lois Brown on August 17, 1941, in Buffalo, New York. She was the daughter of David Brown and Lucile Manheim.14 Edmund and Helene would have two children. Edmund served in the US Army during World War II from August 27, 1943, until March 11, 1946.15 Edmund and his family then settled in Springville, New York, where he continued to practice medicine.16

Later Edmund and Helene retired to Fort Myers, Florida, where Helene died at age 71 on April 24, 1993.17 Edmund died in Cleveland, Ohio, almost exactly a year later on April 21, 1994; he was 81.18 According to his obituary in the Springville Journal, Edmund “was an old-fashioned family physician [who] cared not only for his patients but also for their families and their community. His home was always equipped to see patients after hours and house calls were made often.” The obituary also noted that he was a gifted artist. Edmund and Helene are survived by their children and grandchildren.19

The story of the family of Hirsch Rothschild and his family reminds me of how much the US gained when Germany’s persecution of the Jews forced so many to come here. Hirsch, his son Edmund, and his son-in-law Gustav were all doctors educated and trained in Europe. They came to this country as refugees, and Americans benefited from those skills and that education and dedication. But Mathilde Rosenbaum Rothschild’s death at the hands of the Nazis must remind us that the gifts we Americans may have received from those refugees were not given by them without enduring terrible heartbreak and loss on their part.

- Gustav Rosbasch, World War II draft registration, National Archives at St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; Wwii Draft Registration Cards For New York State, 10/16/1940 – 03/31/1947; Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147, Ancestry.com. U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947; Gustav Rosbasch, passenger manifest, The National Archives in Washington, DC; Washington, DC, USA; Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957; Microfilm Serial or NAID: T715; RG Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004; RG: 85, Ship or Roll Number: Scythia, Ancestry.com. New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957 ↩

- Gertrude Rosbasch, passenger manifest, The National Archives in Washington, DC; Washington, DC, USA; Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957; Microfilm Serial or NAID: T715; RG Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004; RG: 85, Ancestry.com. New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957 ↩

- Edith Rothschild, passenger manifest, The National Archives in Washington, DC; Washington, DC, USA; Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957; Microfilm Serial or NAID: T715; RG Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004; RG: 85, Ship or Roll Number: New York, Ancestry.com. New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957 ↩

- Edmund Rothschild, passenger manifest, The National Archives in Washington, DC; Washington, DC, USA; Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957; Microfilm Serial or NAID: T715; RG Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004; RG: 85, Ship or Roll Number: New York, Ancestry.com. New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957 ↩

- Gustav Rosbasch and family, 1940 US census, Year: 1940; Census Place: Rochester, Monroe, New York; Roll: m-t0627-02848; Page: 4B; Enumeration District: 65-232, Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census ↩

- Edith Rothschild, 1940 US census, Year: 1940; Census Place: Rochester, Monroe, New York; Roll: m-t0627-02842; Page: 6B; Enumeration District: 65-22, Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census ↩

- Edmund Rothschild, 1940 US census, Year: 1940; Census Place: Brighton, Monroe, New York; Roll: m-t0627-02678; Page: 14A; Enumeration District: 28-9, Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census ↩

- Yad Vashem entry found at https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/names/11619667 ↩

- Gustav Rosbasch, Social Security Administration; Washington D.C., USA; Social Security Death Index, Master File, Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014 ↩

-

Gertrude Rosbasch, [Gertrude Rothschild], Gender Female, Birth Date 3 Sep 1910, Birth Place Gudensberg, Death Date 4 Jul 1997, Claim Date 17 May 1973

Father Harry Rothschild, Mother Mathilde Rosenbaum, Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007 ↩ - “Marriage Licenses,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, October 26, 1943, p. 12 ↩

- Edith Miriam Solomon, [Edith Miriam Rothschild], Gender Female, Race White, Birth Date 4 Jul 1911, Birth Place Gudensberg, Federal Republic of Germany, Death Date 28 Jul 2003, Claim Date 19 Jan 1976, Father Harry Rothschild, Mother Mathilde Rosenbaum, Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007. ↩

-

Abram Solomon, Social Security Number 128-09-6834, Birth Date 18 Nov 1899,

Issue year Before 1951, Issue State New York, Last Residence 14617, Rochester, Monroe, New York, USA, Death Date Jun 1971, Social Security Administration; Washington D.C., USA; Social Security Death Index, Master File, Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014 ↩ -

“Dr. Edward [sic] Rothschild to be Married Soon,” Bradford Evening Star and The Bradford Daily Record, Bradford, Pennsylvania · Friday, August 01, 1941, p. 5; Helene Brown Rothschild, Gender Female, Birth Date 30 Jul 1921, Birth Place Minneapolis, Minnesota, Death Date 24 Apr 1993, Father David Brown, Mother Lucile S Manheim,

SSN 057382510, Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007. ↩ - Edmund S Rothschild, Birth Date 30 Jul 1912, Death Date 21 Apr 1994, Cause of Death Natural, SSN 114342498, Enlistment Branch ARMY, Enlistment Date 27 Aug 1943, Discharge Date 11 Mar 1946, Page number 1, Ancestry.com. U.S., Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010. ↩

- “Founder of Medical Group Dies,” Springville Journal, Springville, New York · Thursday, May 05, 1994, p. 6. ↩

- “Helene L. Brown Rothschild,” News-Press, Fort Myers, Florida · Tuesday, April 27, 1993, p. 19; Helene Brown Rothschild, Gender Female, Birth Date 30 Jul 1921, Birth Place Minneapolis, Minnesota, Death Date 24 Apr 1993, Father David Brown, Mother Lucile S Manheim, SSN 057382510, Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007. ↩

- See Notes 15 and 16, supra. ↩

- See Note 16, supra. ↩