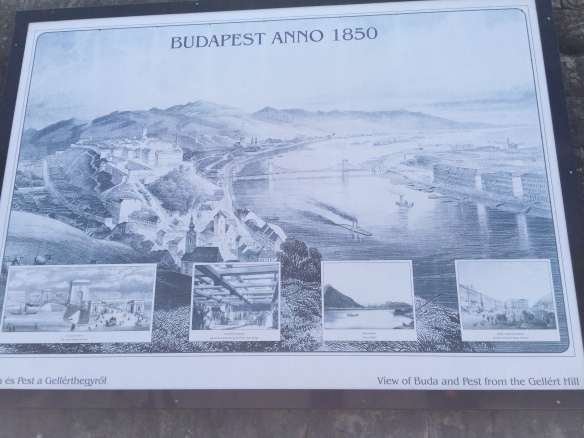

To be honest, Vienna was not originally on our itinerary. We wanted to go to Prague and Budapest and, of course, Poland, and we felt that given the number of days we could travel that that was already an ambitious itinerary. But we could not find non-stop flights even out of NYC to any of those places, and we hate layovers, so we decided to fly in and out of Vienna. It may not make sense to those of you who are regular jetsetters, but getting me on a plane is a big enough accomplishment; making me change planes might send me…flying?

Anyway, we were going to fly in and out of Vienna so we added a day to our trip. It seemed crazy not to spend at least 24 hours in one of the world’s great cities, even though we knew that 24 hours would not be enough to scratch the surface of what there is to see there. It would take some intense prioritizing and great organization to pack even a few top sights into our day.

We actually ended up with a day and a half, as our train from Budapest to Vienna arrived around 2:15 pm, and we were able to check into our hotel (Radisson Blu) quickly and be on our way. The hotel was extremely well-situated for us to see many of the important sites just a short walking distance away. It’s not the Boscolo, but it is a very clean, contemporary, and small boutique hotel.

Just two blocks down the street was the Hofburg Palace where the Habsurgs lived in Vienna. An outdoor music festival was going on that day, and there were crowds gathered to listen to the music—young choral groups performing primarily American music. A bit incongruous—standing in front of an Austrian royal palace, listening to a group singing, “When the Saints Go Marching In.” Our global world at work.

We wandered through the streets, passing many chic stores on Kohlmarket, and reached Graben, where there is a huge square lined with cafes and more fancy shops. We stopped to see St. Stephen’s Cathedral and the all glass Haus Haus across the street. Unlike the Hilton in Buda, this modern structure somehow blended in with the older buildings surrounding it.

We just had to stop and have some Viennese pastry, right? It’s mandatory, I think. If one must drink beer in Prague, one must eat pastry in Vienna. It was very much worth the unnecessary calories. Vienna’s streets were packed with tourists, and there was lots of good people-watching to do from the café.

But we had miles to go in order to see at least some of the city, so off we marched towards the Opera House. Like the Opera House in Budapest, it was a stately and beautiful building. We opted not to do the tour inside this time, preferring to use our time to visit one of the art museums.

It was already late in the afternoon, and we realized that we only had an hour until closing time, so we opted for the smaller Leopold Museum rather than the tremendous Kunsthistorische museum. We were very glad that we did. The museum focuses on the works of Gustav Klimt and Oskar Kokoschka as well as that of some of their less well-known contemporaries, and it does a masterful job of teaching about their art, their lives, and the politics and psychology that lie behind their art. The room dedicated to the influence of Sigmund Freud was particularly well-done; a plaque with a quote from Freud hung near each painting, leaving it to the viewer to see the connection between the words and the art.

We stayed until the museum closed and then wandered back to our hotel, not even realizing how close it was. (We had basically walked a full circle from one side of the center of the city to the other and back without realizing it and were essentially behind the Hofburg Palace when we exited the museum quarter.) We were amazed by how much we had seen in the few short hours since we’d arrived in Vienna.

The next day was jam-packed on my itinerary, but I quickly realized that there was no way we would get to the Schonbrunn Palace, even though I had pre-purchased tickets to go there. It’s about 20 minutes outside of the city center, and since we were seeing the Hofburg Palace that morning, we decided that if you’ve seen one palace, you’ve seen them all. (Where is Spiro Agnew when you need him?) Eliminating the Schonbrunn from the agenda loosened up our day considerably.

The Hofburg Palace was worth seeing; it tells the story of Emperor Franz Joseph and his wife Empress Elizabeth, commonly known as Sisi. In particular, it tells the story of Sisi, who grew up as a young and independent child and married the emperor somewhat reluctantly, knowing that she would lose her freedom by doing so. Eventually she became very unhappy living such a restricted life, and after one of her children died, she became severely depressed. Although she contemplated suicide, in the end she was assassinated in Geneva by an Italian anarchist. Her life story is well-told in the first several rooms in the palace. After that, you then can see many of the lavish rooms where the emperor and empress lived and entertained in the palace.

After the palace tour, we went to see the performance of the Lipizzaner stallions at the Spanish Riding School. This was another event that, like the baths in Budapest, several people said we could not miss. We had standing room tickets, and the place was packed. Within five minutes of the show starting, I almost left. The first “act” involved some newer horses, and it was clear that at least one of them was not at all happy performing. I couldn’t watch as the horse bucked and resisted his trainer’s attempts to control him. We did stay for the next hour, and although the rest of the show involved more experienced horses, I just couldn’t shake the idea that these animals were being forced to do something they were not intended to do. The horses are gorgeous, and if you love horses, you will either love this event or you will hate it. I still am not sure how I feel about it. (We were not allowed to take photos, so I’ve inserted one from the internet.)

After lunch, I went to see the jewels at the Imperial Treasury while Harvey went to finalize our boarding passes for our flight the next morning. The jewels were amazing. I will let the pictures reveal what I saw.

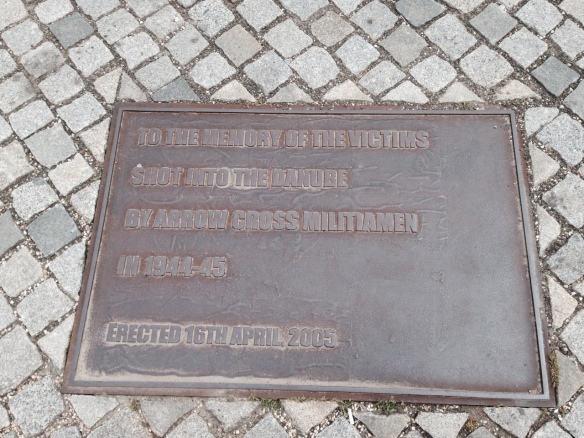

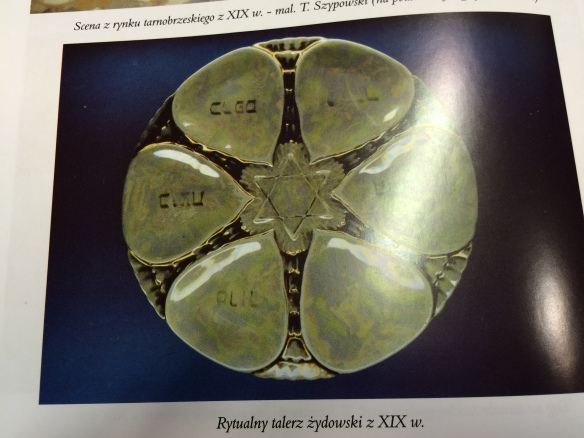

The last thing we wanted to do before leaving Vienna was see some evidence of the Jewish world that once existed there. Vienna had a large and thriving Jewish population before the Holocaust, including many famous artists, writers, musicians, and, of course, Freud. Yet unlike Prague or Krakow or Budapest, there is almost nothing left in what was once the oldest Jewish section of the city to let you know that there once was a vibrant Jewish community there. In that place, called Judenplatz, there are two reminders of the Jewish community: a museum which contains the remains of a medieval synagogue and a Holocaust memorial sculpture. The museum’s exhibit is fascinating. You can actually walk through the remains and see where the bima was, where the ark was, where the men sat to pray.

As for the Holocaust sculpture, it stands in the center of the square, and it is a large cube placed in the center of a larger platform. On the sides of the cube are engraved the names of all the concentration and death camps. I think it is supposed to evoke the sense of being locked inside, given the locked door on the exterior. What was very disturbing about the memorial was the fact that there were many people sitting on the platform, idly eating ice cream and chatting, seemingly oblivious to the purpose of the sculpture.

The memorial to the 65,000 murdered Austrian Jews in the Holocaust at Judenplatz in Vienna. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

That perhaps is itself a metaphor for the Austrian attitude towards the Holocaust for many years after the war: denial. As we learned at the main building of Jewish museum, it was not until fifty years after the war that Austrian officials apologized for their country’s role in the Holocaust. They refused to acknowledge their complicity with the Nazis in the persecution and eventual murders of their Jewish citizens. What had been a large and wealthy and intellectual community had been almost entirely wiped out. Today there is some revival of Jewish life in Vienna, mostly made up of immigrants from the former Soviet Union.

We ended our trip going to the Musikverein, a great music hall in Vienna, where we heard Haydn, Poulenc, and Sibelius. The sounds were as clear as could be, and the music was just wonderful.

Although we saw so much of great beauty in Vienna—the buildings, the pastries, the jewels, the art, and the music, our visit to Judenplatz and to the Jewish museums put an overall damper on my feelings for Vienna. Perhaps I am not being fair; we were there for such a short time, and perhaps a longer visit would have provided me with more perspective. We had no guides in Vienna, just our handy Rick Steve’s guidebook and TripAdviser. I understand that there are a number of stolpersteins in the Second District where the Jewish community was located right before World War II. We did not get there nor did we see where the current synagogues are located or talk to anyone familiar with the city and its history as we had in the other cities. I am sure there is more than what we saw in such a short time—an important lesson to keep in mind in visiting any place. You can’t see it all in a short visit as a tourist.

****

Thus ends my travelogue of our trip to Central Europe. Some concluding thoughts:

- The best way to learn about the history, values, and people of another country is to go there and walk where they walk. If you do, be sure to find a way to talk to someone who lives in that place. Guidebooks are great, group tours may be fine—but nothing beats developing a personal relationship with someone who knows that city like you know your home town and your history. Talk to them about their families, their personal history, and you will learn so much more than you ever could from a book or recorded tour.

- Take notes, take pictures. Memories vanish very quickly. In writing this, I had to go back to my books, notes, photographs, and, yes, the internet, to be sure I had the right name for the right place and the right numbers and dates.

- Travel the way you want to travel. I know many people prefer to travel on organized tours or at least with a group of friends. Call us anti-social, but we have learned that traveling with others means compromising our own priorities. We don’t get to travel as often as we’d like, and when we do, we want to go where we want to go, eat when and where we want to eat, and see and hear what we want to see and hear. It’s really not that hard to research and plan your own trip. Just my opinion, of course. I fully understand that for other people, traveling with others is more comfortable and more fun. Like I said, travel the way you want to travel.

- There is both incredible beauty in the world and incredible evil. Human beings have created incredibly awe-inspiring buildings, music, and art. Each place we visited was a testament to man’s ability to create beauty. Sadly, each place was also a testament to man’s ability to do incredible evil. We tried always to let the beauty remind us that for the most part, human beings are good.

- If you know where your ancestors lived, go there, even if it’s a small town in the middle of nowhere where no traces are left of your ancestors or their community. I understand that some people have too many feelings of anger about the past to do this, but if you don’t feel that way and can go, go there. You will be forever changed.

Thank you to all who have followed me through this telling of our trip. I will now return to a focus on genealogy, but I felt a real need to write about this trip for so many reasons, not the least of which is to keep a record for me about what I saw and what I felt. It is not an experience I ever want to forget.