When I started this blog back in October, 2013, I never anticipated that it would help family members find me. But that has proven to be an incredible unexpected benefit of publishing this blog. This is one of those stories.

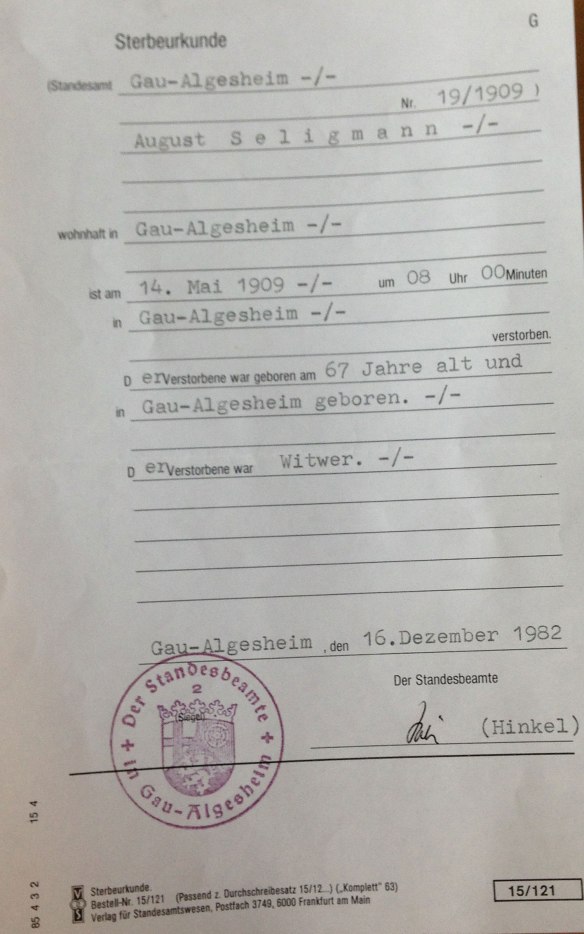

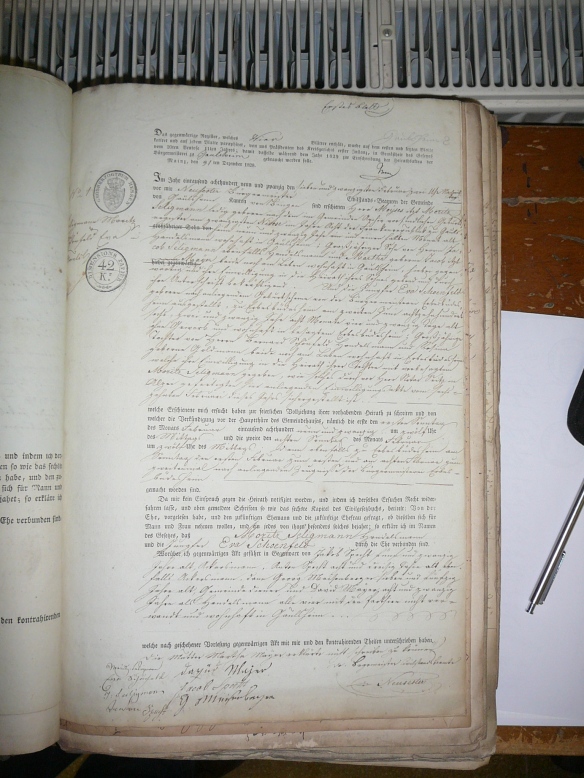

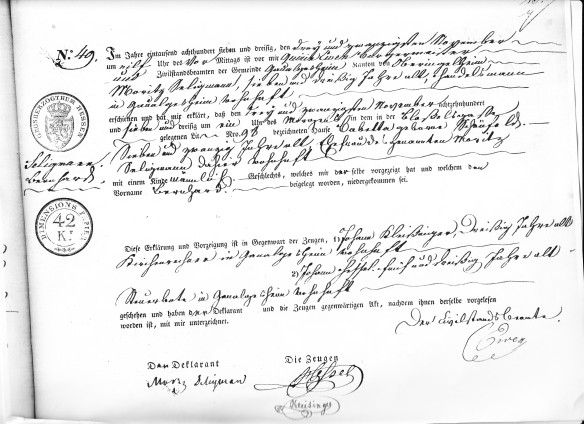

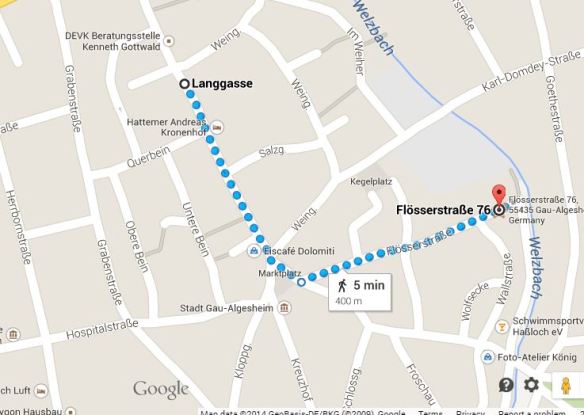

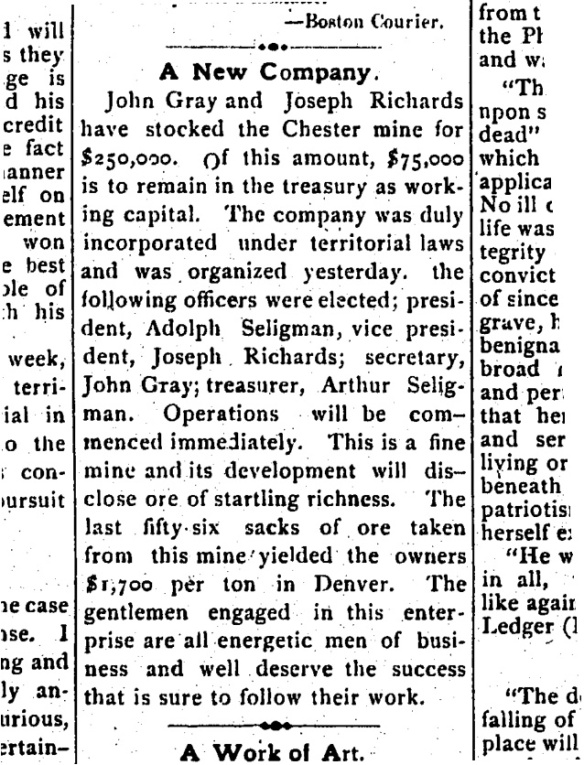

Several weeks ago, I received a comment on the blog from a man named Wolfgang Seligmann, saying he was the son of Walter Seligmann, that he lived near Gau-Algesheim, and that he had found my blog while doing some research on his family. He asked me to email him, which I did immediately, and we have since exchanged many emails and learned that we are third cousins, once removed: his great-great-grandparents were Moritz Seligmann and Babetta Schoenfeld, my great-great-great-grandparents. His great-grandfather August was the brother of Sigmund, Adolph and Bernard Seligman, the three who had settled in Santa Fe in the mid-19th century. Wolfgang sent me a copy of August’s death certificate.

(Translations in this post courtesy of Wolfgang Seligmann except where noted: Registry-Office Gau-Algesheim: August Seligmann, living in Gau-Algesheim died the 14th of May 1909 at 8 a.m. in Gau-Algesheim. He was 67 years old and born in Gau-Algesheim. He was a widower.)

Our families had probably not been in touch since Bernard died in 1902 (or perhaps when Adolph died in 1920). And now through the miracle of the internet and Google, Wolfgang had found my blog with his family’s names in it and had contacted me. What would our mutual ancestors think of that? It even seems miraculous to me, and I live in the 21st century.

Fortunately, Wolfgang’s English is excellent (since my knowledge of German is…well, about five words), and so we have been able to exchange some information about our families, and I have learned some answers to questions I had about the Seligmanns who stayed in Germany. With Wolfgang’s permission, I would like to share some of those stories.

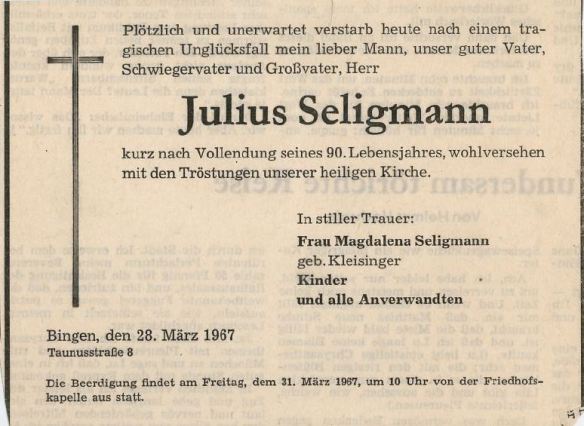

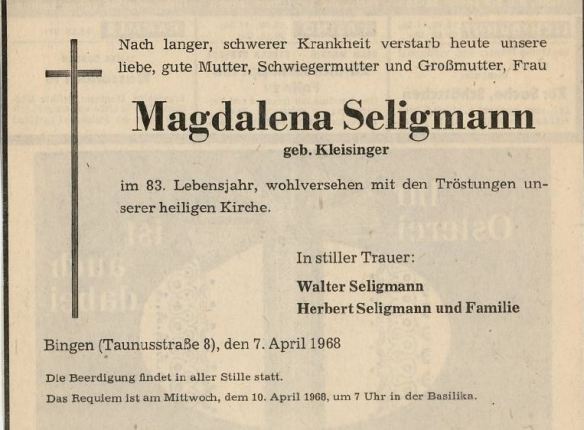

Wolfgang’s grandfather was Julius Seligmann, the second child and oldest son of August Seligmann and his wife Rosa Bergmann. Julius was born in 1877 in Gau-Algesheim. As I wrote about here, Julius was one of the Seligmanns written about in Ludwig Hellriegel’s book about the Jews of Gau-Algesheim. He had been a merchant in the town. On December 1, 1922, Julius had married a Catholic woman named Magdalena Kleisinger, who was born in Gau-Algesheim on July 9, 1882, and had himself converted to Catholicism. Julius and Magdalena had two sons, Walter, who was born February 10, 1925, and Herbert, born July 27, 1927. Julius and his family had left Gau-Algesheim for Bingen in 1939 after closing the store in 1935.

I had wondered why Julius had closed the store and then relocated to Bingen, and I asked Wolfgang what he knew about his grandfather’s life. According to Wolfgang, his father Walter and uncle Herbert did not like to talk about the past, but Wolfgang knew that when Julius married and converted to Catholicism, his Jewish family was very upset and did not want to associate with him any longer. In fact, Julius was forced to pay his siblings a substantial amount of money for some reason relating to his store in Gau-Algesheim, and that payment caused him and his family a great deal of financial hardship. According to Wolfgang, Julius no longer had enough money to pay for his own home, and thus he and his family moved to Bingen in 1939 where they lived with Magdalena’s family or friends for some time.

The Hellriegel book also made some puzzling (to me) references to the military records of Wolfgang’s father and uncle, saying that they had been “allowed” to enlist in the army, but then were soon after dismissed. Wolfgang explained that the German authorities did not know how to treat Catholic citizens with Jewish roots. Wolfgang said that his father Walter had trained to be a pharmacist, but the Nazis would not allow him to work with anything poisonous. In addition, his father was not permitted to be in the army; instead he was ordered by the authorities to work on the Siegfried Line, which was originally built as a defensive line by the Germans during World War I. In August 1944, Hitler ordered that it be strengthened and rebuilt, and according to Wikipedia, “20,000 forced labourers and members of the Reichsarbeitsdienst (Reich Labour Service), most of whom were 14–16-year-old boys, attempted to re-equip the line for defence purposes.” Walter Seligmann was one of those forced laborers.

Here is a photograph of Walter Seligmann, Wolfgang’s father:

As for Wolfgang’s uncle Herbert, he was sent by the local police to the army, but the army would not accept him. He was dismissed and sent back to Bingen, where he was required to work in a warehouse until the war ended.

Julius Seligmann died in 1967, and his wife Magdalena died the following year. Walter Seligmann died in 1993, and his brother Herbert died in 2001.

There are some very bitter ironies in these stories. Julius and his family were not accepted by his Jewish family because they were Catholic, but the Nazis did not accept them either because they had Jewish roots. As I commented to Wolfgang, prejudice of any sort is so destructive and unacceptable. His family experienced it from two different directions.

Not that the two examples here can be equated in any way. Although all prejudice is wrong, prejudice that leads to genocide is utterly reprehensible, an evil beyond comprehension for anyone who has a moral compass. I have already written about my own personal horror and pain when I realized that I had family who had been murdered by the Nazis. Wolfgang told me more about some of those who lost their lives to Hitler and his evil forces.

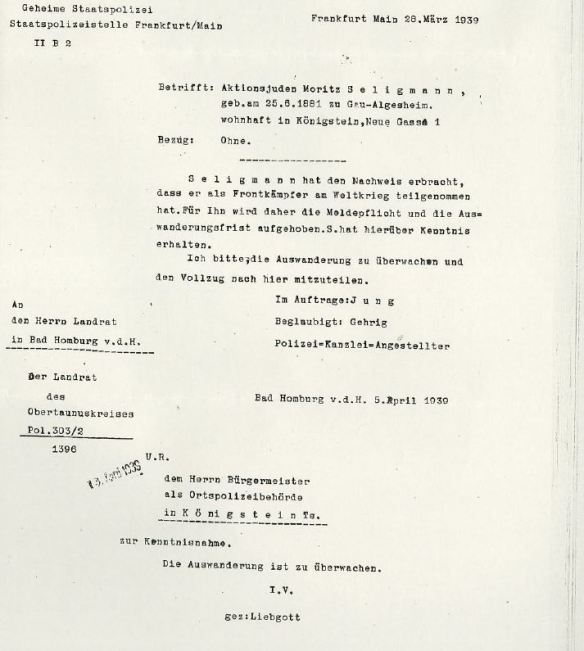

One victim was his great-uncle Moritz Seligmann (the grandson of Moritz Seligmann, my 3x-great-grandfather, and a son of August Seligmann). My information about his fate comes from two websites that Wolfgang shared with me. According to these two sites, Moritz Seligmann, Julius’ younger brother, was born on June 25, 1881. He fought in World War I for Germany, spent two years in captivity, and was honored with the Hindenburg Cross or Cross of Honor for his service. Despite this, in the aftermath of Kristallnacht, on November 11, 1938, Moritz was arrested in Konigstein, where he had been living since 1925. He was sent to the concentration camp at Buchenwald.

Moritz wrote to the authorities in Konigstein, pointing out that he was the recipient of the Hindenburg Cross. He was released from Buchenwald in December on the condition that he emigrate by March 31, 1939. He was required to report to the police in Konigstein twice a week until then, and if he had not emigrated by the deadline, he was to be arrested. On March 28, 1939, however, the Gestapo lifted the emigration order and the reporting requirement in light of Moritz’s service during World War I.

Here is a copy of the Gestapo letter, lifting the emigration order. I found this a particularly chilling document to see.

Wolfgang helped me translate this letter as follows: Frankfort, March 20, 1939. Concerning: the “Aktionsjude” Moritz Seligmann born June 25, 1881, Gau-Algesheim, residing in Konigstein. Seligmann has provided proof that he was a soldier in the World War as a combatant. Therefore the reporting obligation and emigration order is lifted for him. I would ask the emigration (?) to supervise and notify us here.

As explained to me by Wolfgang and by Wikipedia, the “Aktionsjude” referred to 26,000 Jews who were deported in the aftermath of Kristallnacht, as was Moritz Seligmann, as part of an effort to frighten other Jews to leave Germany. Unfortunately, not enough of them did.

Despite the lifting of the order to emigrate, Moritz had hoped to immigrate to the US. For various bureaucratic reasons described here, he was unable to get clearance to emigrate. On June 10, 1942, he was picked up by the Nazis and transported somewhere to the east. Exactly where and when he died is not known.

Wolfgang and his family, after researching the fate of Moritz, informed the town of Konigstein of their findings, and the town agreed to place a “stolperstein” in memory of Moritz Seligmann near his home in Konigstein. A stolperstein (literally, a stumbling blog) is a memorial stone embedded in the ground to memorialize a victim of the Holocaust. Here is a photograph of Wolfgang at the ceremony when Moritz Seligmann’s stolperstein was installed in Konigstein.

Behind him is a man who knew Moritz and remembered when Moritz was initially arrested in 1938, clinging to his Hindenburg Cross, believing it would save him from the murderous forces of the Nazis. It may have stalled his murder, but it did not save him.

Wolfgang also told me about the fate of another sibling of his grandfather Julius, his younger sister Anna. Anna, born in Gau-Algesheim in 1889, had married Hugo Goldmann, and they had a daughter Ruth, born in 1924 in Neunkirchen, a town about 80 miles southwest of Gau-Algesheim, where Anna and Hugo had settled. Between 1939 and 1940, many people from this area near the border with France were evacuated to locations in central Germany, and Anna, Hugo, and Ruth ended up in Halle, Germany, 350 miles to the northeast of Neunkirchen. On June 1, 1942, they were all deported from Halle to the Sobibor concentration camp where they were all killed. Click on each name to see the memorial pages established by the town of Halle in memory of Anna, Hugo, and Ruth.

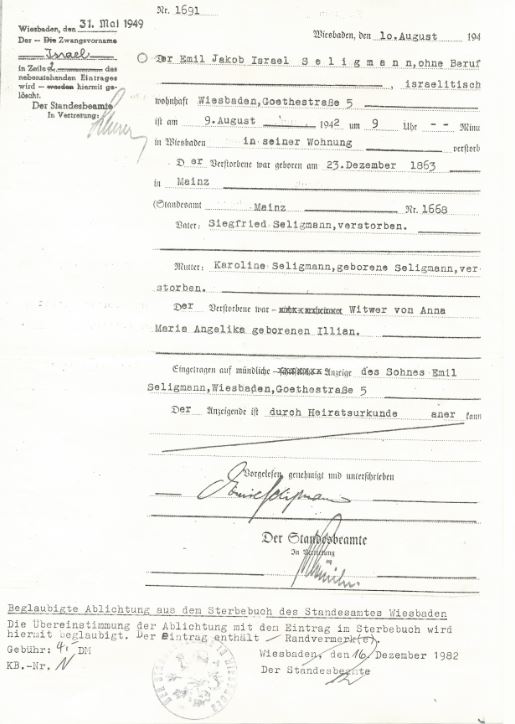

Finally, Wolfgang told me about another member of the family. Moritz Seligmann (the elder) had had a daughter Caroline with his first wife, Eva Schoenfeld. Caroline was the half-sister of my great-great-grandfather Bernard. She had married a man named Siegfried Seligmann, perhaps a cousin. Their son, Emil, died in Wiesbaden on August 9, 1942, when he was 78 years old.

(Wiesbaden: The Emil Jakob Israel Seligmann, without profession, “israelitisch” [presumably meaning Jewish], living in Wiesbaden, Gothestraße Nr. 5, died on 9th of August 1942 in his Apartment. He was born on 23th of December 1863 in Mainz.

Father: Siegfried Seligmann, deceased. Mother: Karoline Seligmann, nee Seligmann, deceased. He was widower of Anna Maria Angelika born as Illien. The death was announced by Emil Seligmann, his son, living Goethestraße Nr.5.

The stamp in the left hand margin says: Wiesbaden, 31th of May 1949. The “Zwangsvorname”Israel is deleted. Zwangsvorname translates as “forced first name,” meaning that the name Israel had been required by the Nazis, I assume as a way to identify him as Jewish.

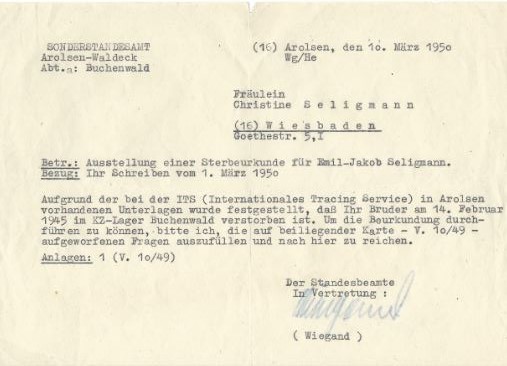

Emil had a son, also named Emil, who died in Buchenwald, as this record attests.

(To: Miss Christine Seligmann, Wiesbaden, Goethestr. Nr. 5,1

From: Special registry-office in Arolsen-Waldeck, department Buchenwald

Subject: death-certification for Emil-Jakob Seligmann, Your letter from the 1. of March 1950

Based on the documents of the International Tracing Service in Arolsen it is proved, that your brother died on 14th of February 1945 in the Concentration Camp Buchenwald. )

I imagine that this is not the end of the list of the Seligmanns who were murdered during the Holocaust, and I imagine that there are also many other family members I never knew about who were killed by the Nazis, whether they were named Schoenfeld, Nussbaum, Dreyfuss, Goldschlager, Rosenzweig, Cohen, or Brotman or something else. I just haven’t found them yet.

Wolfgang and I plan to keep on exchanging stories, pictures, documents, and other information. We have also already talked about meeting someday and walking in the footsteps of our mutual ancestors. What an honor it will be to be with him as we share our family’s story.