Meier Blumenfeld IIB, who died in 1922, and his wife Sarchen, who died in 1930, were survived by three of their five children: Moses Blumenfeld III and his wife Sarah Rothschild and their son Julius; Hermann Blumenfeld III and his wife Elsa Drucker and their three children, Eric, Hilde, and Liselotte; and Rosa Blumenfeld and her husband Julius Hess. As of 1933 when Hitler came to power, they were all living in Germany.

Tragically, all three of Meier IIB and Sarchen’s children were murdered in the Holocaust. Moses IIB and Sarah were deported to the Litzmannstadt Ghetto in Lodz on October 20, 1941, and died sometime thereafter. Fortunately, their son Julius escaped to Argentina in 1936. I don’t know what happened to Julius afterwards, but at least he managed to avoid the fate of his parents.1

Moses IIB’s sister Rosa and her husband Julius Hess were also both killed by the Nazis. They were deported on June 11, 1942, from Frankfurt either to the Sobibor death camp and/or to the camp at Majdanek, where they were murdered.2

Hermann Blumenfeld III and his wife Elsa were also murdered by the Nazis, as were their daughter Hilde and her family, despite the fact that they all had left Nazi Germany. Hilde had immigrated to Amsterdam in March 1934, and she had married Julius Seelig on April 28, 1937, in Amsterdam. Julius was born in Reichensachen, Germany, on December 10, 1908, to Joseph Seelig and Paula Wallach. Hilde and Julius had one child, a daughter Hanna born in Amsterdam on October 12, 1938. Julius and Hilde were divorced on June 9, 1942, and Julius soon remarried another woman, Margot Pauline Aharon, in July 1942.

Here are the Amsterdam registration cards for Hilde, Julius, and Hanna that report this information:

Amsterdam City Archives, Archive cards , archive number 30238 , inventory number 78

Municipality : Amsterdam, Period : 1939-1960, found at https://archief.amsterdam/indexen/deeds/98533418-6d7f-56a3-e053-b784100ade19

Amsterdam City Archives, Archive cards , Archive cards , archive number 30238 , inventory number 719, Municipality : Amsterdam, Period : 1939-1960 found at https://archief.amsterdam/indexen/deeds/9853340a-857d-56a3-e053-b784100ade19

Amsterdam City Archives, Archive cards , archive number 30238 , inventory number 719

Municipality : Amsterdam, Period : 1939-1960, found at https://archief.amsterdam/indexen/deeds/9853341a-53f7-56a3-e053-b784100ade19

Hilde’s parents Hermann and Elsa came to Amsterdam later than Hilde, arriving in May 1939, according to Hermann’s Amsterdam registration card.

Amsterdam City Archives, Archive cards , archive number 30238 , inventory number 78

Municipality : Amsterdam

Period : 1939-1960 found at https://archief.amsterdam/indexen/persons?sa=%7B%22person_1%22:%7B%22search_t_geslachtsnaam%22:%22Blumenfeld%22,%22search_t_voornaam%22:%22Hermann%22%7D%7D

But escaping to Amsterdam did not keep any of them safe. According to records at Yad Vashem, Hermann and Else were sent to the Westerbork Detention Camp in 1943 and from there deported to Auschwitz where they were both killed on February 11, 1944.

Hilde and her daughter Hanna were also first sent to Westerbork in August 1943 and then to Auschwitz. Hilde died on January 31, 1944, and her five-year-old daughter Hanna on February 11, 1944, according to Yad Vashem.

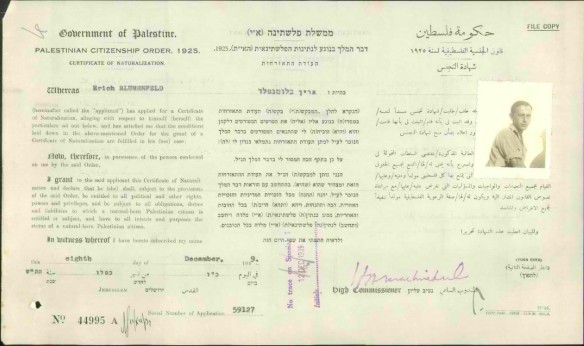

Fortunately, Hilde’s two siblings survived the Holocaust. Erich Blumenfeld immigrated to Palestine on September 13, 1937, and became a naturalized citizen there on December 19, 1939.3

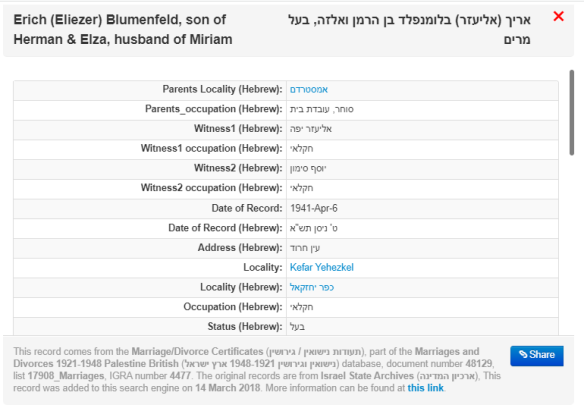

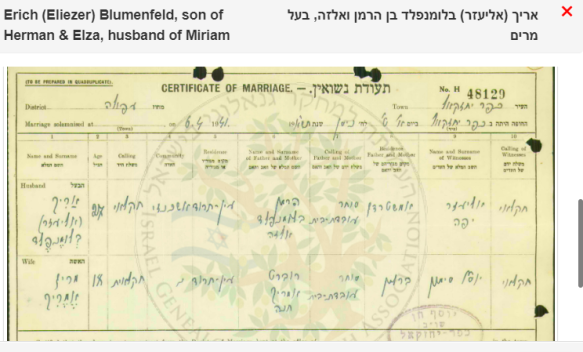

Erich married Miriam Emerich, daughter of Robert and Hannah Emerich, on April 6, 1941.4

Erich changed his name in 1948 to Eliezer Shadmon. Shadmon means farm in Hebrew, and according to Erich/Eliezer’s application for naturalization, he was working as a farmer at Ein Harod at that time, as seen in the images above.5 Unfortunately, I’ve not yet found any further information about Erich/Eliezer.

Liselotte Blumenfeld, the youngest child of Hermann III and Else, immigrated to the US and arrived in New York City on August 5, 1937. She was heading to Lexington, Kentucky, according to the ship manifest,6 and in 1940, she was living with James and Nanette Strause in Fayette, Kentucky and working as a nurse, presumably for their seven year old son. I don’t know why Liselotte chose Kentucky as her destination, but I assume there was some friend or family member living there when she immigrated or she had arranged the job before leaving Germany. (I’ve recently learned that another branch of the Blumenfeld family that I’ve yet to research settled in Kentucky long before the 1930s, so perhaps that was Liselotte’s connection. To be determined…)

On January 10, 1943, Liselotte, referred to here as Liesel Lotte Bloomfield, married Corporal Herbert Isaak in Louisville, Kentucky.

Herbert was born in Munich, Germany, on March 21, 1920, and had immigrated to the US on April 25, 1941; he’d enlisted in the US Army on January 5, 1942. His parents were Emil Charles Isaak and Therese Meyer.7 Liselotte and Herbert had one child born in the 1940s. According to his obituary, Herbert had survived the Dachau Concentration Camp and had served as a field-commissioned second lieutenant in the US Army at the Nuremberg Trials.8

In 1950, the family was living in New York City, and Herbert was working as a traveling salesman for a “ladies suits and coats factory.”9 The family must have relocated to the South at some later date because, according to Herbert’s obituary, “he was a traveling sales representative of women’s coats in Virginia and the Carolinas and had a showroom in Charlotte, N.C.”10 Herbert died on November 18, 2001, in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina; he was 81. Liselotte outlived him by thirteen years; she was just a few days shy of her 97th birthday when she died on November 5, 2014. Herbert and Liselotte were both buried at Florence National Cemetery in Florence, South Carolina.11

I haven’t yet determined whether Liselotte Blumenfeld Isaak or Erich Blumenfeld/Eliezer Shadmon have living descendants. Nor have I found more information about their cousin Julius Blumenfeld, the son of Moses IIB. I am hoping that there are more descendants alive to carry on the legacy of Meier Blumenfeld IIB and his wife Sarchen Moses and their children.

- “Uruguay, listas de pasajeros, 1888-1980,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C33M-19T3?cc=2691993 : 30 June 2020), > image 1 of 1; Archivo General de la Nación, Dirección Nacional de Migración (General Archive of the Nation, National Migration), Montevideo. Also, see Arolsen Archives, Digital Archive; Bad Arolsen, Germany; Lists of Persecutees 2.1.1.1, Description Reference Code: 02010101 oS, Ancestry.com. Free Access: Europe, Registration of Foreigners and German Persecutees, 1939-1947 ↩

- The Gedenbuch and Yad Vashem records mention both camps. I guess the evidence of where Rosa and Julius ended up is unclear, but their ultimate fate is not. ↩

- Erich Blumenfeld, Palestine Immigration File, found at the Israel Archives website at https://www.archives.gov.il/catalogue/group/1?kw=erich%20blumenfeld ↩

- Marriage record found at the Israel Genealogy Research Association website by searching for Erich Blumenfeld. https://genealogy.org.il/AID/ ↩

- Name change found at the IGRA website by searching for Eliezer Shadmon. https://genealogy.org.il/AID/ ↩

- Liselotte Brilea Ingeborg Blumenfeld, ship manifest, Year: 1937; Arrival: New York, New York, USA; Microfilm Serial: T715, 1897-1957; Line: 21; Page Number: 37,

Ancestry.com. New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957 ↩ - Herbert Jsaak [Herbert Isaak] Gender: Male Race: White Birth Date: 21 Mar 1920

Birth Place: Munich, Federal Republic of Germany, Death Date: 18 Nov 2001, Father:

Emil Jsaak Mother: Therese Meyer SSN: 046143654, Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007; Herbert Isaak, Petition for Naturalization, The National Archives at Atlanta; Atlanta, GA; Petitions For Naturalization , Compiled 1906-1978; NAI: 1275754; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States; Record Group Number: 21, Ancestry.com. Kentucky, U.S., Naturalization Records, 1906-1991; Herbert Isaak, National Archives at College Park; College Park, Maryland, USA; Electronic Army Serial Number Merged File, 1938-1946; NAID: 1263923; Record Group Title: Records of the National Archives and Records Administration, 1789-ca. 2007; Record Group: 64; Box Number: 04782; Reel: 142, Ancestry.com. U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946 ↩ - “Herbert Isaak,” Myrtle Beach Sun-News, November 21, 2001, p. 35. ↩

- Herbert Isaak and family, 1950 US census, United States of America, Bureau of the Census; Washington, D.C.; Seventeenth Census of the United States, 1950; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census, 1790-2007; Record Group Number: 29; Residence Date: 1950; Home in 1950: New York, New York, New York; Roll: 4377; Sheet Number: 12; Enumeration District: 31-2180, Ancestry.com. 1950 United States Federal Census ↩

- See Note 8, supra. ↩

- Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/138910393/liesel-isaak: accessed 21 September 2022), memorial page for Liesel Bloomfield Isaak (23 Nov 1917–5 Nov 2014), Find a Grave Memorial ID 138910393, citing Florence National Cemetery, Florence, Florence County, South Carolina, USA; Maintained by Danny & Judy Ard (contributor 47789022); Liesel Isaak, Rank: T/5, Death Age: 96, Birth Date: 23 Nov 1917, Death Date: 5 Nov 2014, Interment Place: Florence, South Carolina, USA, Cemetery Address: 803 East National Cemetery Road, Cemetery Postal Code: 29501, Cemetery: Florence National Cemetery, Section: 11 Plot: 37, War: World War II, Branch of Service: US Army

Relative: Herbert Isaak, Comments: Wife, National Cemetery Administration; U.S. Veterans’ Gravesites, National Cemetery Administration. U.S., Veterans’ Gravesites, ca.1775-2019; ↩