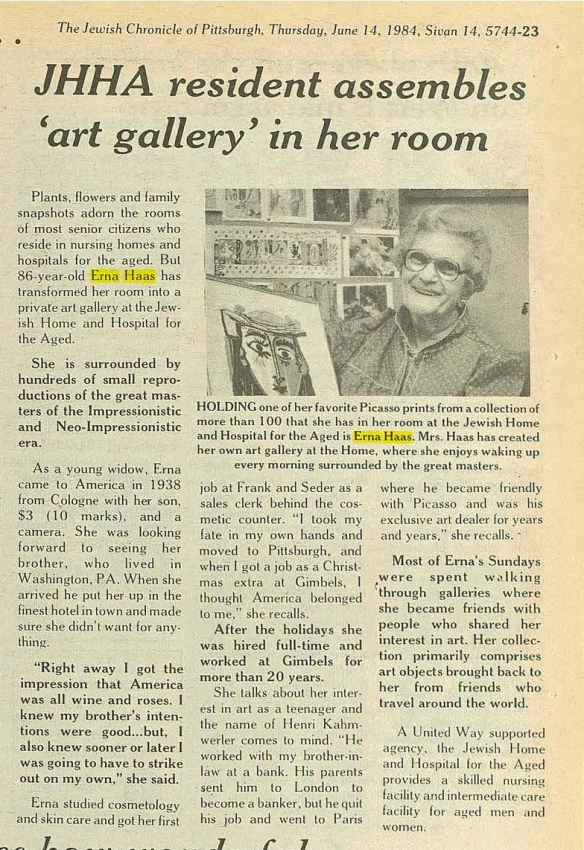

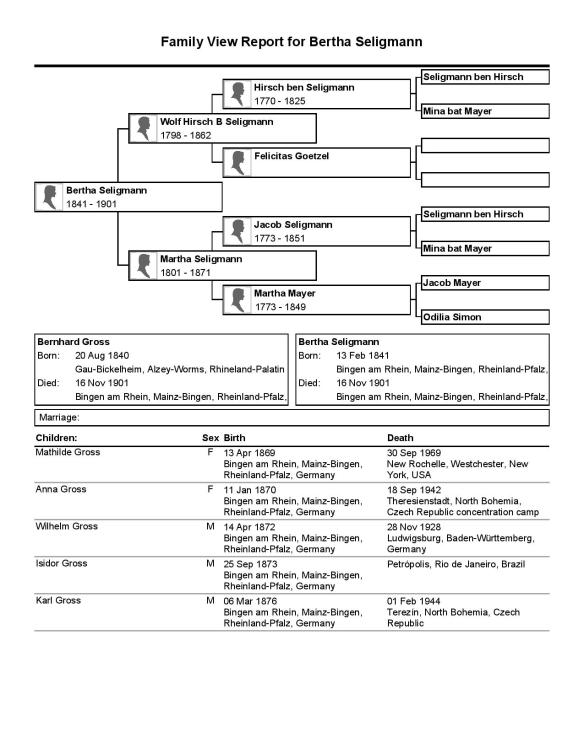

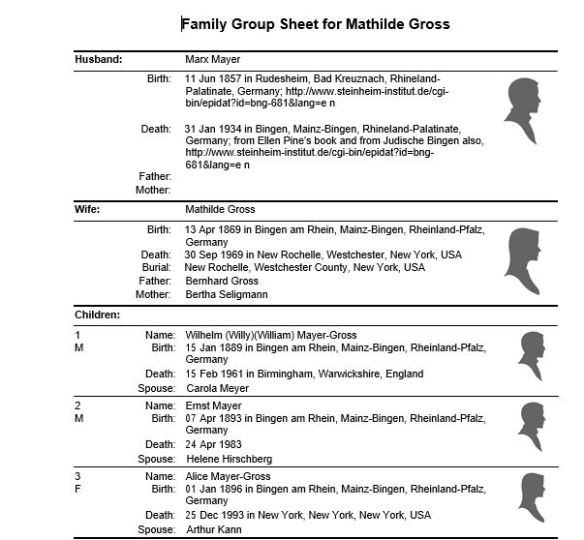

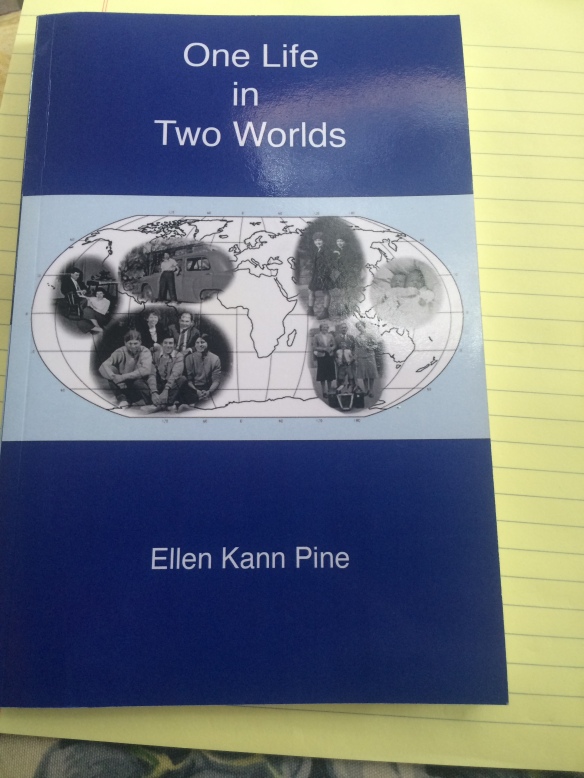

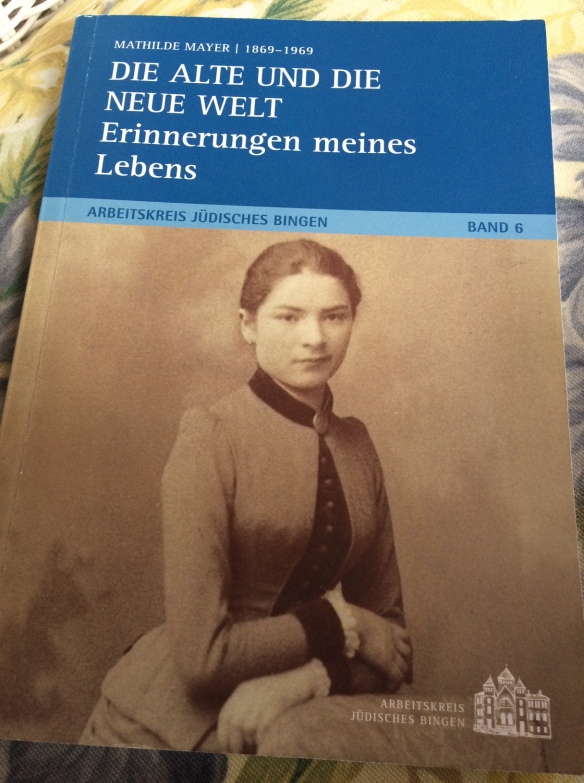

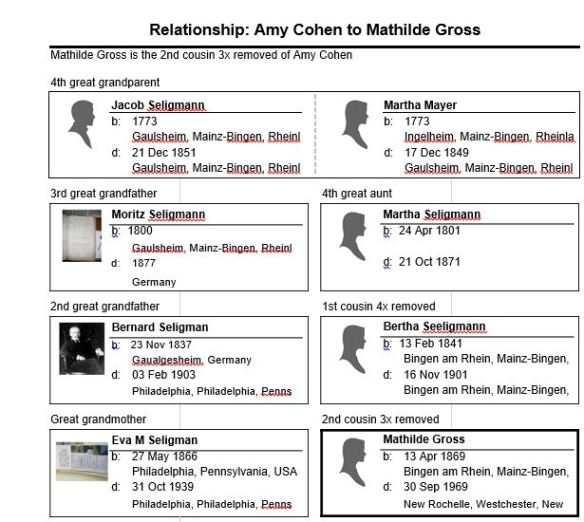

As I wrote last time, Mathilde Gross Mayer and her three children, Wilhelm, Ernst, and Alice, all safely emigrated from Germany in the 1930s after the Nazis had taken over. Not all of her siblings and other relatives were as fortunate. Mathilde had four younger siblings, Anna, Wilhelm, Isidor, and Karl. This post will tell the story of Anna Gross, Mathilde’s younger and only sister. Anna, like Mathilde, was my second cousin, three times removed. We are both descendants of Jacob Seligmann.

If the birth dates provided by her brother Isidor in Mathilde’s book are accurate, Anna Gross was born September 1, 1870, or a year and a half after Mathilde’s birth on April 14, 1869.[1] Anna married William Lichter of Bruchsal in 1892, whose father Leopold Lichter owned a wine distillery. Anna and William settled in Stuttgart, where they had a son Paul (1893) and a daughter Irma (1898).

According to a biography of William and Anna and their family published on a Stolperstein site about the family, in 1916 Wilhelm Lichter purchased a stately house on a large lot with a terrace, courtyard, garage, and a garden with pergolas and two garden sheds.

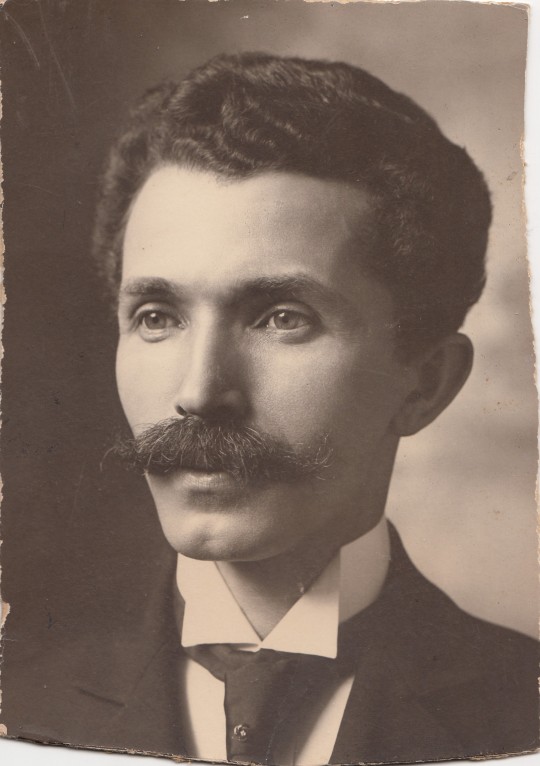

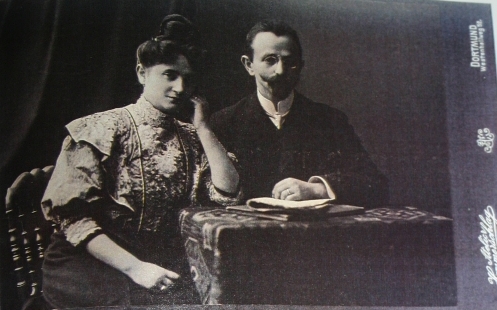

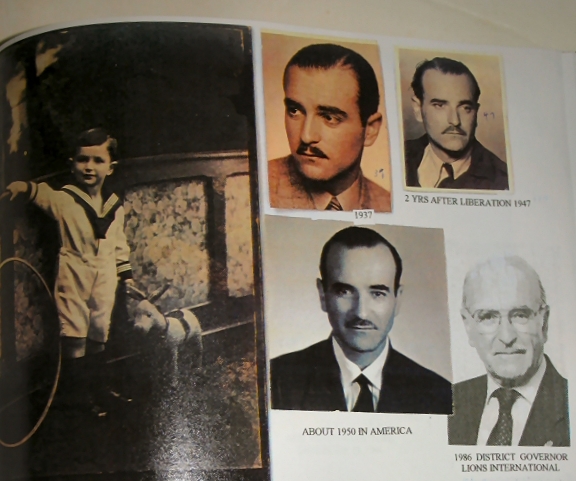

Wilhelm and Anna (Gross) Lichter, 1927 passport photos

http://www.stolpersteine-stuttgart.de/index.php?docid=749

According to the Stolperstein site, Anna and Wilhelm’s son Paul Lichter married Marie Hirsch on February 17, 1919; they would have two daughters born in the 1920s, Renate and Lore.

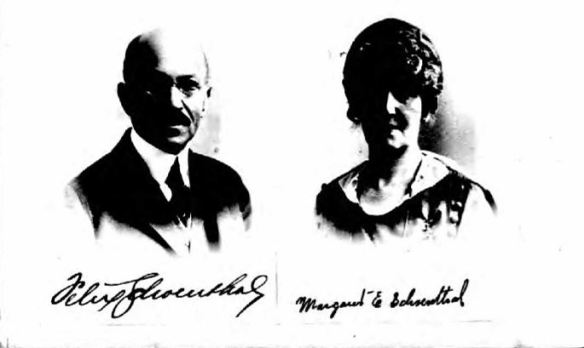

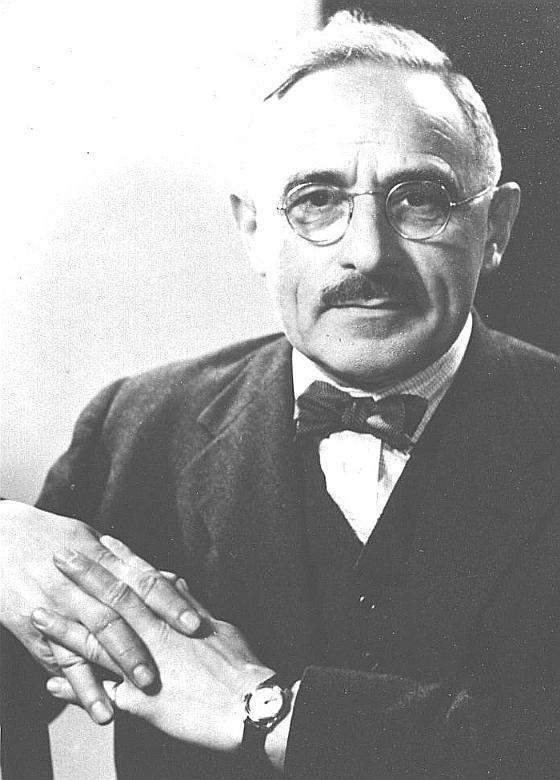

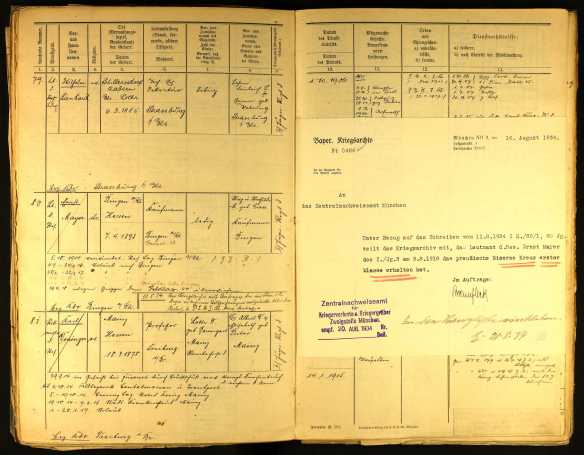

Just nine months after her brother married, Irma Lichter married Max Wronker on November 2, 1919. Max had served as an officer in the German army during World War I and had been awarded the Iron Cross, Second Class.

Max and Irma would have two children, a daughter Gerda and a son Erich.

Max Wronker and Irma Lichter Wronker and their two children Gerda and Erich, 1927

Courtesy of the Wronker family

According to the introduction to the family papers on file with the Leo Baeck Institute (Guide to the Papers of the Lili Wronker Family 1843-2002 (AR 25255 / MF 737)), Max was the son of Herman Wronker and Ida Friedeberg of Frankfurt; Herman Wronker was an extremely successful merchant with department stores in a number of cities in Germany. He also was a founder of a successful cinema business in Frankfurt. According to an October 25, 2007 article in Der Spiegel (“Lili und die Kaufhauskönige”), Herman Wronker was invited in the 1920s by Carl Laemmle of Universal Pictures to come to Hollywood, but Wronker was loyal to Germany and did not want to leave. (Thank you to my cousin Wolfgang for find the Der Spiegel article for me.)

The Der Spiegel article also reported that during the 1920s, the Wronker department store business employed over three thousand people with annual sales exceeding 35 million Reich marks. When the Depression came in 1929, Herman’s son Max, husband of Irma Lichter, took over the management of the business and was forced to sell two of the Wronker department stores.

Wronker department store in Frankfurt

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AFrankfurt_am_Main%2C_Zeil%2C_Kaufhaus_Wronker_AK_1925.jpg

Max Wronker had a sister Alice, and I was very fortunate to make a connection through Ancestry.com with Trisha, whose husband is Alice Wronker’s grandson. Trisha has known several members of the extended Lichter and Wronker families, and she has a wonderful collection of photographs of the family, which she generously shared with me. The family pictures in this post are all courtesy of Trisha and her family, except where otherwise noted.

Alice Wronker Engel, Ida Friedeberg Wronker, and Irma Lichter Wronker, Courtesy of the Wronker family

First cousins: Ruth , daughter of Alice Wronker Engel and Herman Engel, and Gerda, daughter of Max Wronker and Irma Lichter Wronker

Courtesy of the Wronker family

Both the Wronker and Lichters families were obviously quite wealthy and living a good life in Germany until the Nazis came to power. Then everything changed. According to the same 2007 Der Spiegel article, by the end of March, 1933, the Wronkers were no longer allowed on the premises of their businesses, and the entire business was “aryanized” in 1934.

The article also indicated that at that point Max and Irma (Lichter) Wronker decided to leave Germany and move to France, where Max tried unsuccessfully to start a leather goods company. He then received a tourist visa to go to Cairo to work as an adviser to a department store business there, but was unable to receive an official work permit and earned so little money that he was forced to sell much of the family’s personal property.

Max and Irma did not come to the United States until after the war ended.

Meanwhile, Anna (Gross) and Wilhelm Lichter also were suffering from Nazi persecution. As reported in the Stolperstein biography, on April 1, 1938, Irma’s father Wilhelm Lichter sold the lovely home he owned in Stuttgart for 125,000 Reich marks, which was far below its value (according to assessors determining reparations after the war). Wilhelm and Anna were allowed to rent the second floor of the home after they sold it for a one year term.

On April 26, 1938, the Germans enacted the Decree on the Registration of the Property of Jews pursuant to which all Jews were required to assess all their assets and register them if their value exceeded 5,000 Reich marks. The Nazis also prohibited Jews from owning or operating a business, except for limited exceptions to allow services rendered by Jews to other Jews. Additional information about these property deprivations can also be found here in a December 25, 1938 article by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency (“Nazi Restrictions, Special Taxes Strip Jews of Wealth”).

As a result of these regulations, Wilhelm Lichter was forced to pay substantial amounts of money to the German government in 1938. After Kristallnacht, the government also passed additional laws, increasing substantially the taxes that Jews were forced to pay under the pretext that they were obligated to pay for the damage caused by Kristallnacht. Wilhelm again was required to use a great deal of his assets to pay for these taxes.

Then, in the aftermath of Kristallnacht on November 9 and 10, 1938, Wilhelm and Anna’s son Paul Lichter was arrested and sent to the concentration camp at Dachau, where he was imprisoned until December 6, 1938. After he was released, Paul decided to leave Germany with his wife Marie and their children; his two daughters were no longer allowed to attend school after May, 1938, and he had had to sell his business.

In order to emigrate, Paul had to comply with the Reichsfluchtsteuer, or Reich Flight Tax, a tax imposed on those wishing to leave Germany. As explained by this Alphahistory site, “this law required Jews fleeing Germany to pay a substantial levy before they were granted permission to leave. The flight tax was not an invention of the Nazis; it was passed by the Weimar Republic in 1931 to prevent Germany from being drained of gold, cash reserves and capital. But the Nazi regime expanded and increased the flight tax considerably, revising the law six times during the 1930s. In 1934 the flight tax was increased to 25 per cent of domestic wealth, payable in cash or gold. Further amendments in 1938 required emigrating Jews to leave most of their cash in a Gestapo-controlled bank.”

Another site about the Holocaust indicated that, “As a result of these levies and others, those Jews fortunate enough to emigrate were able to save only a small portion of their assets. For Jews remaining in Germany after 1938, whatever assets they had left were kept in blocked accounts in specified financial institutions, from which only a modest amount could be withdrawn for their living expenses.”

In order to pay this tax, Paul and Marie had to sell their personal property, including their jewelry, silverware, coffee service, sugar bowls, and candlesticks to a pawnshop and then pay a tax of 67,000 Reich marks, or the equivalent of about $30,000 in 1938 US dollars. That would be equivalent to almost $500,000 dollars in 2016.

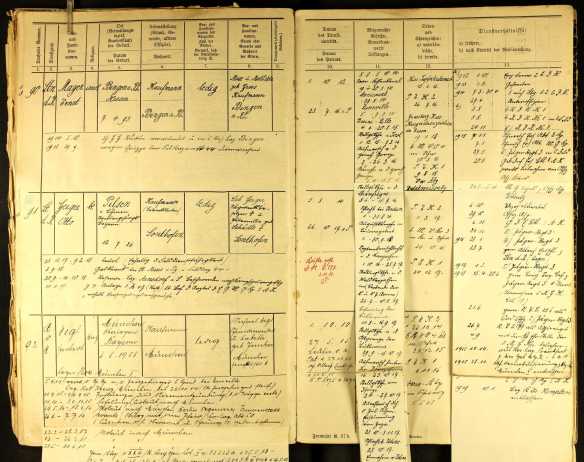

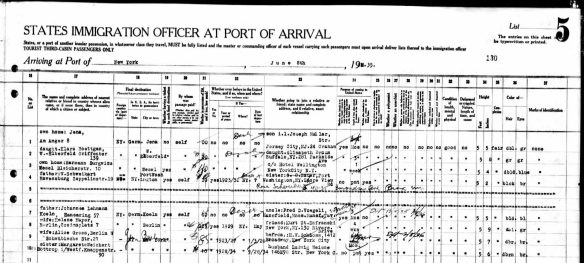

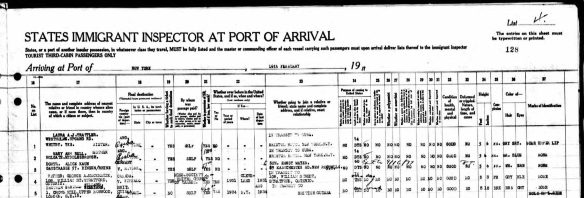

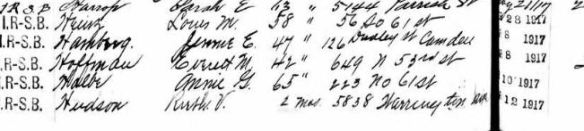

Paul emigrated first, arriving in New York on March 11, 1938. According to the ship manifest (line 9), he was a liquor dealer. He listed the person he was going to as a cousin named Meyer Gross living at 30 Parcot Avenue in New Rochelle, New York.

![Paul Lichter on 1938 ship manifest to NY Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867. Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives at Washington, D.C. Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957. Microfilm Publication T715, 8892 rolls. NAI: 300346. Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service; National Archives at Washington, D.C. Supplemental Manifests of Alien Passengers and Crew Members Who Arrived on Vessels at New York, New York, Who Were Inspected for Admission, and Related Index, compiled 1887-1952.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/paul-lichter-ship-manifest-1938-p-2.jpg?w=584&h=589)

Paul Lichter on 1938 ship manifest to NY, line 9

Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867. Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives at Washington, D.C. Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957. Microfilm Publication T715, 8892 rolls. NAI: 300346. Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service; National Archives at Washington, D.C. Supplemental Manifests of Alien Passengers and Crew Members Who Arrived on Vessels at New York, New York, Who Were Inspected for Admission, and Related Index, compiled 1887-1952.

It also made sense that Paul would be going to New Rochelle since he had family members living in that city. In fact, 30 Parcot Avenue was only half a mile from where Paul’s cousin Alice Mayer Kann was living in 1940 at 17 Argyle Avenue in New Rochelle as well and just two blocks from where Paul’s cousin Ernst Mayer was living at 94 Hillside Avenue in New Rochelle.

I searched the 1940 census to see if there was a Meyer Gross living at 30 Parcot Road in 1940, and I discovered that Kurt Kornfeld and his family were living at that location in 1940. Kurt Kornfeld was one of Ernst Mayer;s partners in Black Star Publishing, which they founded after they escaped Nazi Germany, as I discussed here. And living in the Kornfeld home as a lodger in 1940 was a 72 year old German-born woman named Matilda Mayer, who I believe I am safe in assuming was Mathilde Gross Mayer, Paul’s aunt.

But who then was Meyer Gross? I don’t know. I checked both the 1938 and 1940 directories for New Rochelle (the 1939 was not available online), and there was no person with that name in either directory. Since the name was entered by hand on the manifest, perhaps it was written incorrectly by the person entering the name. Maybe it was “Mathilde Gross,” her birth name? I don’t know.

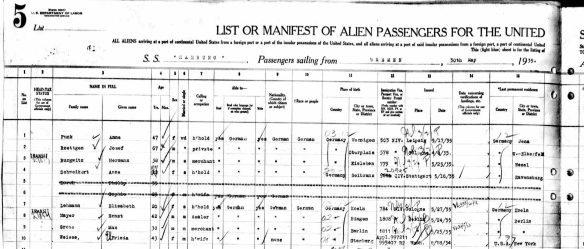

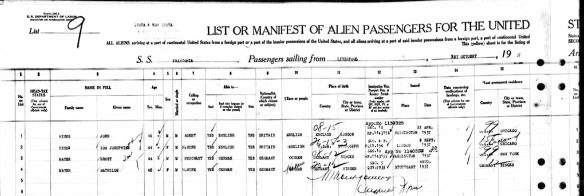

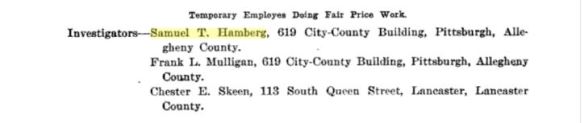

On June 8, 1939, Paul and Marie’s eighteen year old daughter Renate sailed to New York alone; she was to be met by another “cousin” Heinz “Anspacher,” who resided at 404 West 116th Street in New York City. (See line 13.)

![Renate Lichter on 1939 ship manifest, line 13 Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867. Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives at Washington, D.C. Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957. Microfilm Publication T715, 8892 rolls. NAI: 300346. Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service; National Archives at Washington, D.C. Supplemental Manifests of Alien Passengers and Crew Members Who Arrived on Vessels at New York, New York, Who Were Inspected for Admission, and Related Index, compiled 1887-1952.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/renate-lichter-1939-ship-manifest-line-13-p-2.jpg?w=584&h=580)

Renate Lichter on 1939 ship manifest, line 13

Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867. Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives at Washington, D.C. Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957. Microfilm Publication T715, 8892 rolls. NAI: 300346. Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service; National Archives at Washington, D.C. Supplemental Manifests of Alien Passengers and Crew Members Who Arrived on Vessels at New York, New York, Who Were Inspected for Admission, and Related Index, compiled 1887-1952.

Heinz was the son of Max Ansbacher and Emilia Dinkelspiel, neither of whom appear to have a connection to the Gross or Licther or Hirsch families. Perhaps this was a friend of the family? I don’t know. (I hate paragraphs that end with I don’t know, and that’s the second time in this post.)

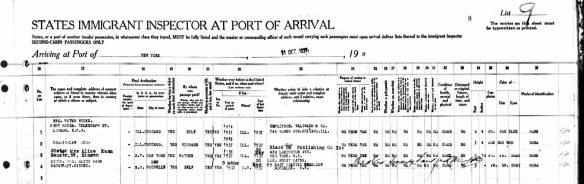

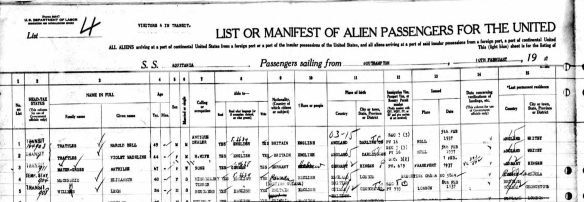

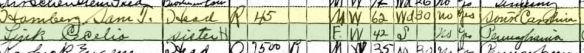

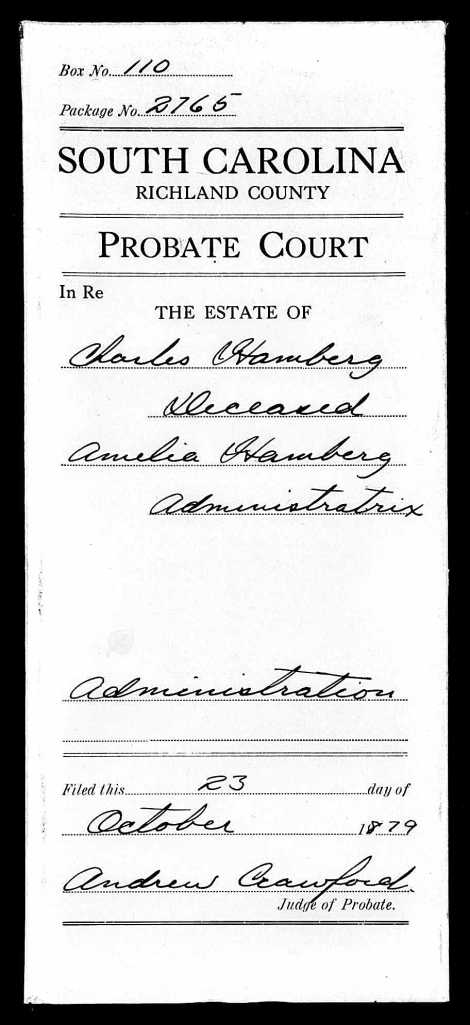

But if her father Paul had arrived in 1938, why was Renate going to Heinz Ansbacher in 1939? Had Paul returned to Europe after his trip in 1938? On March 1, 1940, Paul, Marie, and their younger daughter sailed from Liverpool to New York, and although Marie and her daughter listed their last permanent residence as Stuttgart, Paul’s last permanent residence was stated as Birmingham, England. They all listed Ernst Mayer, Paul’s cousin, as the person they were going to in the United States.

![Paul, Marie, and Lore Lichter on 1940 ship manifest, lines 13-15 Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867. Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives at Washington, D.C. Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957. Microfilm Publication T715, 8892 rolls. NAI: 300346](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/paul-lichter-and-family-on-1940-manifest-lines-13-14-15-p-2.jpg?w=584&h=629)

Paul, Marie, and Lore Lichter on 1940 ship manifest, lines 13-15

Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867. Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives at Washington, D.C. Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957. Microfilm Publication T715, 8892 rolls. NAI: 300346

![Paul, Marie, and Lore Lichter on the 1940 UK ship manifest Ancestry.com. UK, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012. Original data: Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and successors: Outwards Passenger Lists. BT27. Records of the Commercial, Companies, Labour, Railways and Statistics Departments. Records of the Board of Trade and of successor and related bodies. The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, England.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/paul-lichter-and-family-on-1940-uk-manifest.jpg?w=584&h=817)

Paul, Marie, and Lore Lichter on the 1940 UK ship manifest

Ancestry.com. UK, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012.

Original data: Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and successors: Outwards Passenger Lists. BT27. Records of the Commercial, Companies, Labour, Railways and Statistics Departments. Records of the Board of Trade and of successor and related bodies. The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, England.

Anna died less than a month later on September 18, 1942. Wilhelm lasted five more months, dying on February 6, 1943.

Stolpersteine for Wilhelm Lichter and Anna Gross Lichter

http://www.stolpersteine-stuttgart.de/index.php?docid=749

Their son-in-law’s parents, Hermann and Ida Wronker, were also murdered; according to Der Spiegel, by 1939, almost all of their property had been confiscated by the Nazis. In 1941, they were living in France and were sent to the internment camp at Gurs, where they were later deported to Auschwitz. They were killed there in 1942.

Herman and Ida Wronker with their four grandchildren, Erich, Gerda, Ruth, and Marion, courtesy of the Wronker family

But all the children and grandchildren of Herman and Ida (Friedeberg) Wronker and Anna (Gross) and Wilhelm Lichter survived and, like so many of those who escaped from Nazi Germany, they had to start over with almost nothing.

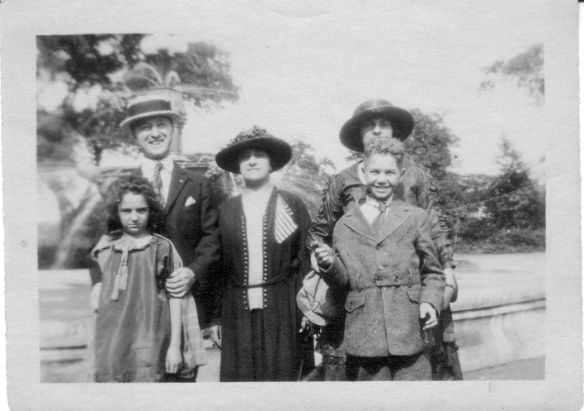

Here are some members of the extended family years later.

From left to right, standing: Max Wronker, Paul Lichter, Marie Hirsch Lichter, Lili Cassel Wronker, Renate Lichter, Alice Wronker Engel, Irma Lichter Wronker, Erich .Wronker, unknown, Edith Cassel.

Seated, left to right, Marion Engel and two unknown women

Courtesy of the Wronker family

I don’t know how people coped with the unfathomable cruelty inflicted upon them and their loved ones, but once again I am inspired by the resilience of the human spirit.

[1] Another secondary source reports that Anna was born on November 1, 1870, but I am going to assume that Anna’s own brother knew her birthday. I’ve no primary source to use to determine for sure.

![Ernst Mayer and family passenger manifest August 11, 1936 Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/ernst-mayer-and-family-august-1936-manifest-p-2.jpg?w=584&h=619)

![Philadelphia College of Pharmacy See page for author [CC BY 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/philadelphia_college_of_pharmacy_and_science_front_of_build_wellcome_v0029143.jpg?w=584&h=299)

![Cecilia Link death certificate Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/cecilia-link-death-cert.jpg?w=584&h=494)

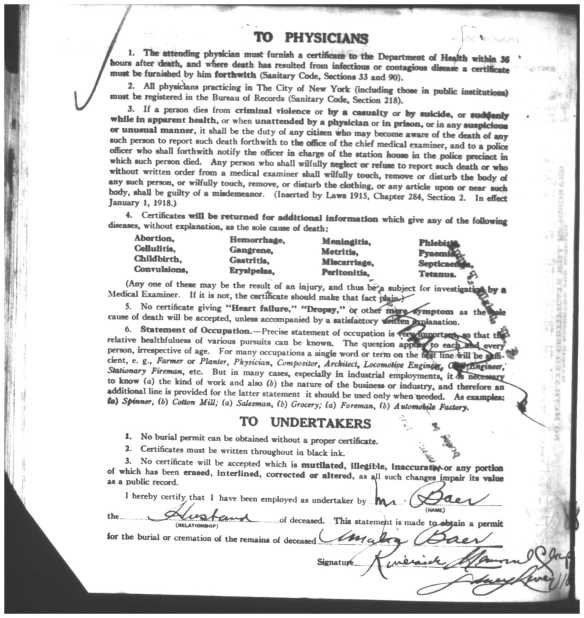

![Death certificate of Hattie Baer, daughter of Amalia Hamberg Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/hattie-baer-death-certificate.jpg?w=584&h=561)

![Charles Hamberg and Mary Hanchey marriage record 1853 Ancestry.com. North Carolina, Marriage Records, 1741-2011 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Original data: North Carolina County Registers of Deeds. Microfilm. Record Group 048. North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, NC.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/charles-hamberg-marriage-record.jpg?w=584&h=725)

![Abraham Hamberg death record 1854 Ancestry.com. Savannah, Georgia, Select Board of Health and Health Department Records, 1824-1864, 1887-1896 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. This collection was indexed by Ancestry World Archives Project contributors. Original data: City of Savannah, Georgia. Savannah, Georgia, Select Board of Health and Health Department Records, 1822–1864, 1887–1896. Subseries 5600HE-050 and 5600HA-010. Microfilm, 27 reels. City of Savannah, Research Library & Municipal Archives, Savannah, Georgia](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/abraham-hamberg-death-record-savannah-george.jpg?w=584&h=449)

![Abraham Hamberg burial record Ancestry.com. Savannah, Georgia, Cemetery and Burial Records, 1852-1939 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012. Original data: Savannah Georgia Cemetery and Burial Records. Savannah, Georgia: Research Library & Municipal Archives City of Savannah, Georgia.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/abraham-hamberg-burial-record-1854.jpg?w=584&h=81)