You might want to open a bottle of wine as you read this post.

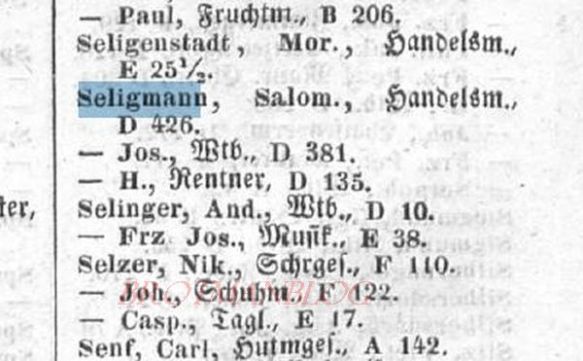

As I wrote last time, Caroline Seligmann (my 4x-great-aunt) and Moses Morreau had two children, Levi and Klara. This post will focus on Klara and her descendants.

Klara was born in Worrstadt on July 9, 1838:

Klara Morreau birth record, July 9 1838

Morreau birth records 1838-29

I have not had success in finding a marriage record for Klara, but I know from her death record and her son’s birth record that she married Adolph (sometimes Adolf) Sichel. I have neither a birth nor a death record for Adolph, but I do have a photograph of Adolph’s gravestone in Bingen, which identifies his birth date as April 10, 1834. [1]

Adolph Sichel was the son of Hermann Sichel and Mathilde Neustadt of Sprendlingen, later Mainz. Hermann Sichel was the founder of the renowned wine producing and trading business, H. Sichel Sohne. Although it is beyond the scope of my blog to delve too deeply into the story of the Sichel wine business, a little background helps to shed light on Adolph, Klara, and their descendants. According to several sources, Hermann Sichel started the family wine business with his sons in 1856 in Mainz, Germany.

In 1883, the company expanded to Bordeaux, France, where it established an office to procure wines for sales by Sichel in Mainz, London, and New York City. The sons and eventually the grandsons worked in various branches of the business, some working in the French office, some in London, and some in Mainz. The business continued to expand and is still in business today; it is perhaps best known in popular culture as the maker of Blue Nun, a wine that was quite successful in the 1970s and 1980s. One writer described it as “a single, perfectly positioned product, a Liebfraumilch whose blandness seemed just the ticket for the hundreds of thousands of new wine drinkers, not just in the US but also in the UK. “

Adolph was not one of the sons who relocated from Germany. He and Klara had two children born and raised in Germany. Their daughter Camilla Margaretha Sichel was born on February 4, 1864, in Sprendlingen, according to Nazi documentation:

UPDATE: Aaron Knappstein was able to get a copy of Camilla’s birth record:

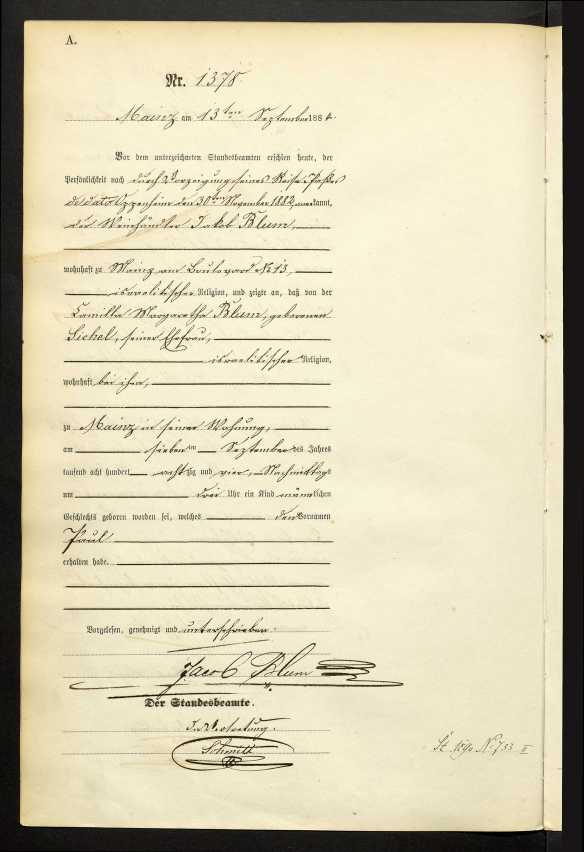

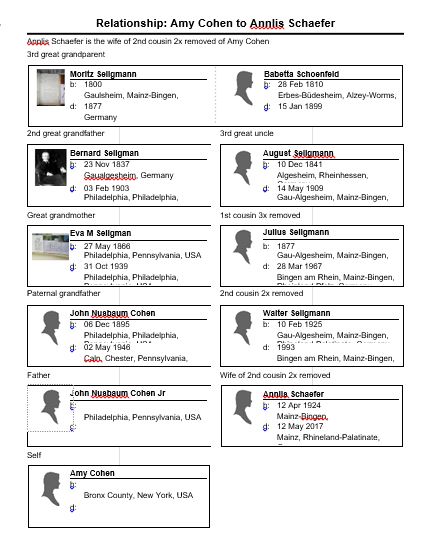

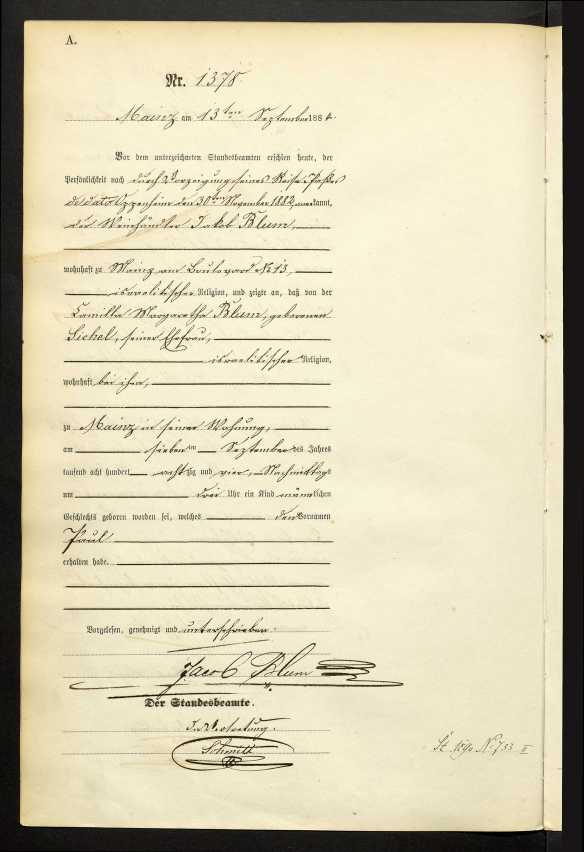

Camilla Sichel married Jakob Blum, who was born April 3, 1853, in Nierstein, Germany. They had four children, all born in Mainz: Paul (1884), Willy (1886), Richard (1889), and Walter (1893):

Paul Blum birth record, September 7, 1884

Ancestry.com. Mainz, Germany, Birth Records, 1872-1900 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

Original data: Personenstandsregister Geburtenregister 1876-1900. Digital images. Stadtarchiv Mainz, Mainz, Germany.

Willy Blum birth record

February 21, 1886

Ancestry.com. Mainz, Germany, Birth Records, 1872-1900 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

Original data: Personenstandsregister Geburtenregister 1876-1900. Digital images. Stadtarchiv Mainz, Mainz, Germany.

Richard Blum birth record

June 8, 1889

Ancestry.com. Mainz, Germany, Birth Records, 1872-1900 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

Original data: Personenstandsregister Geburtenregister 1876-1900. Digital images. Stadtarchiv Mainz, Mainz, Germany.

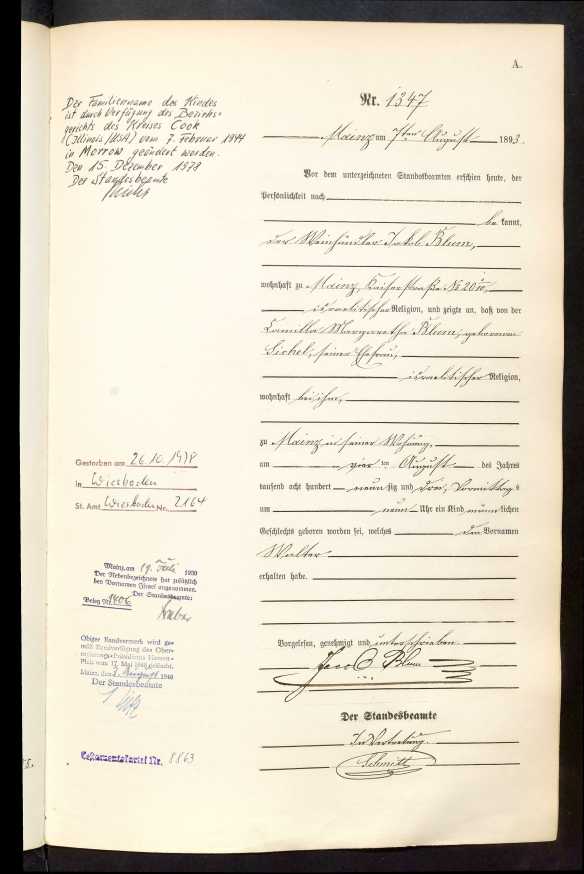

Walter Blum birth record

August 4, 1893

Ancestry.com. Mainz, Germany, Birth Records, 1872-1900 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

Original data: Personenstandsregister Geburtenregister 1876-1900. Digital images. Stadtarchiv Mainz, Mainz, Germany.

Paul died as a young boy in 1890 and is buried in the Jewish cemetery in Mainz.

Paul Blum, Mainz Jewish Cemetery Courtesy of Camicalm Find A Grave Memorial# 176111502

Camilla Sichel Blum’s husband Jakob Blum died August 22, 1914; he was 61 years old:

Jakob Blum death record

Ancestry.com. Mainz, Germany, Deaths, 1876-1950 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015.

Original data: Personenstandsregister, Sterberegister, 1876-1950. Mainz Stadtarchiv.

He was buried in the Mainz Jewish cemetery where his young son Paul had also been buried:

Jakob Blum gravestone, Mainz Jewish Cemetery

Courtesy of Camicalm

Find A Grave Memorial# 177633476

His wife Camilla would survive him by almost thirrty years.

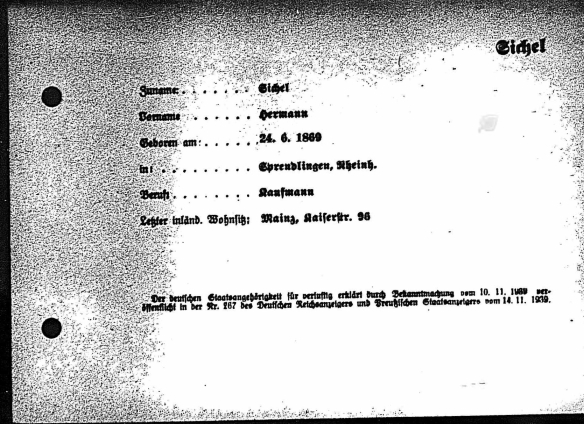

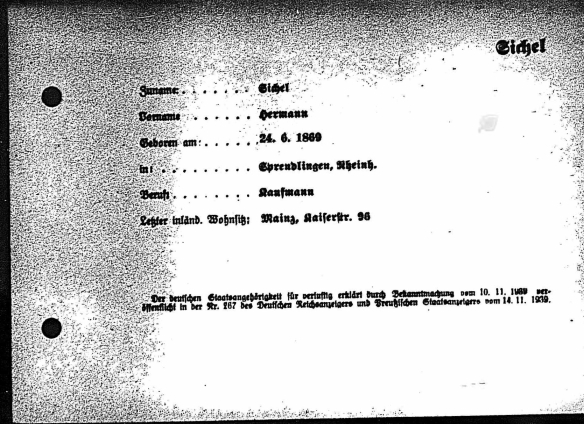

Adolph Sichel and Klara Morreau also had a son named Hermann. I found Hermann’s birth date and place, June 24, 1869, in Sprendlingen, in the Name Index of Jews Whose German Nationality Was Annulled by the Nazi Regime database on Ancestry, a horrifying but presumably reliable source, given the meticulousness with which the Nazis kept records on Jews:

Hermann Sichel in Ancestry.com. Germany, Index of Jews Whose German Nationality was Annulled by Nazi Regime, 1935-1944 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

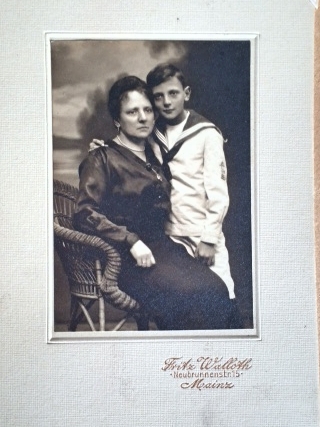

On April 14, 1905, Hermann married Maria Franziska Trier, who was born on May 11, 1883, in Darmstadt, Germany, to Eugen Trier and Mathilde Neustadt. Maria was 21, and Hermann was 35.

Marriage record of Hermann Sichel and Maria Trier

Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv; Wiesbaden, Deutschland; Collection: Personenstandsregister Heiratsregister; Signatur: 901; Laufende Nummer: 98

Hermann and Maria had two sons, Walter Adolph (1906) and Ernst Otto (1907).

Camilla and Hermann’s father Adolph Sichel died on April 30, 1900, as seen above on his gravestone; Hermann’s older son Walter Adolph was obviously named at least in part for Adolph. Klara Morreau Sichel died on April 2, 1919. Adolph and Klara are buried in Bingen.

Klara Morreau Sichel death record, Apr 2, 1919

Ancestry.com. Mainz, Germany, Deaths, 1876-1950 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015.

Original data: Personenstandsregister, Sterberegister, 1876-1950. Mainz Stadtarchiv.

The families of both Camilla Sichel Blum and Hermann Sichel remained in Germany until after Hitler came to power in 1933. Then they all left for either England or the United States.

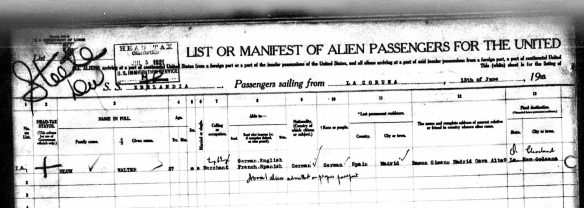

Two of Camilla’s sons, Richard and Walter, ended up in the US. Walter arrived first—on April 27, 1939.

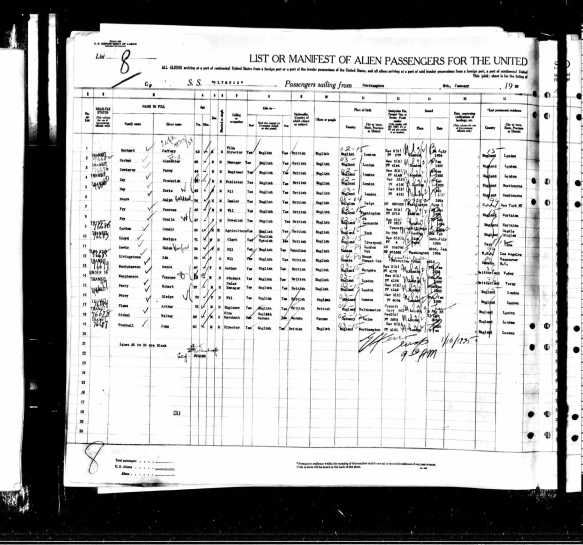

Walter Blum ship manifest 1939

Year: 1939; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: T715, 1897-1957; Microfilm Roll: Roll 6319; Line: 1; Page Number: 42

Description

Ship or Roll Number : Roll 6319

Source Information

Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line].

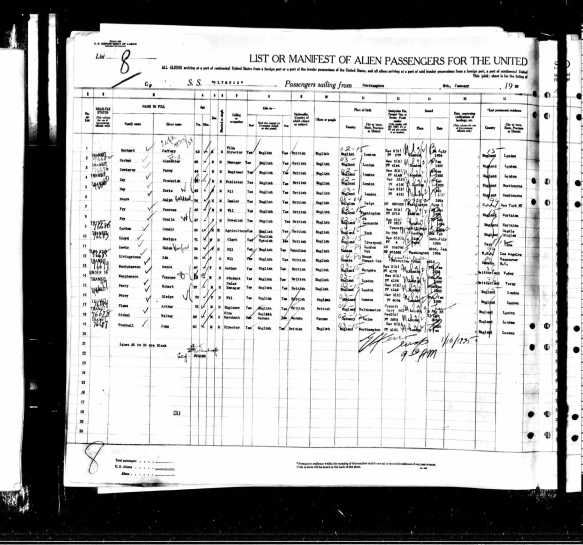

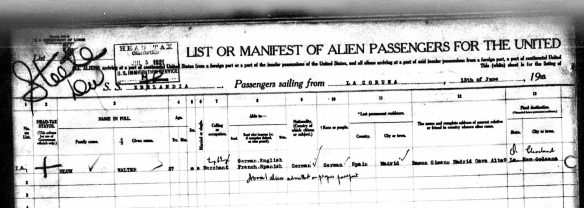

(Walter had actually visited the US many years before in 1921 when he was 27 years old; the ship manifest indicates that he was going to visit his “uncle” Albert Morreau in Cleveland. Albert was in fact his first cousin, once removed, his mother Klara Morreau’s first cousin.)

Walter Blum 1921 ship manifest

Ancestry.com. New Orleans, Passenger Lists, 1813-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2006.

Original data: Selected Passenger and Crew Lists and Manifests. National Archives, Washington, D.C.View all sources.

Richard arrived a few months after Walter on August 29, 1939, listing his brother Walter as the person he was going to:

Richard Blum 1939 ship manifest

Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867. Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives at Washington, D.C.

On the 1940 census, both Richard and Walter were living in the Harper-Surf Hotel in Chicago. Richard was fifty, Walter 46. Both were unmarried and listed their occupations as liquor salesmen. Walter had changed his surname to Morrow, I assume to appear less German. It seems he chose a form of his grandmother Klara’s birth name, Morreau:

Richard Blum and Walter Morrow on 1940 US census

Year: 1940; Census Place: Chicago, Cook, Illinois; Roll: T627_929; Page: 81A; Enumeration District: 103-268

CHICAGO CITY WARD 5 (TRACT 613 – PART)

Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census [database on-line]

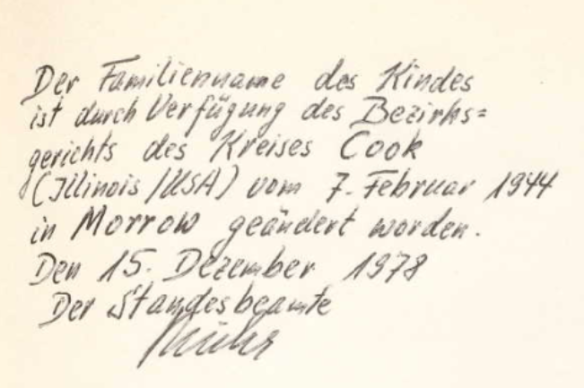

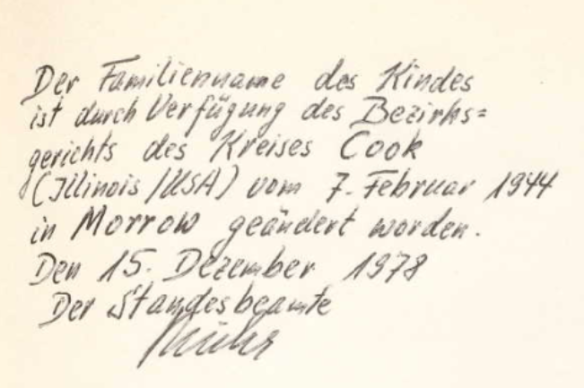

Walter had his name legally changed to Morrow on February 7, 1944, in Chicago, according to this notation on his birth record:

Notation on Walter Blum’s birth record regarding his name change; Walter Blum birth record

August 4, 1893

Ancestry.com. Mainz, Germany, Birth Records, 1872-1900 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

Original data: Personenstandsregister Geburtenregister 1876-1900. Digital images. Stadtarchiv Mainz, Mainz, Germany.

Both brothers registered for the World War II draft in 1942. Richard was now living at the Hotel Aragon in Chicago and working for Geeting & Fromm, a Chicago wine importing business.

Richard Blum World War II draft registration

The National Archives at St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; World War II Draft Cards (Fourth Registration), for The State of Illinois; Record Group Title: Records of the Selective Service System, 1926-1975; Record Group Number: 147; Series Number: M2097

Walter was still living at the Harper-Surf Hotel and working for Schenley Import Corporation, a liquor importing business.

Walter Blum Morrow draft registration World War II

The National Archives at St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; World War II Draft Cards (Fourth Registration), for The State of Illinois; Record Group Title: Records of the Selective Service System, 1926-1975; Record Group Number: 147; Series Number: M2097

Both brothers also became naturalized citizens of the United States in 1944.

Richard died in 1961; his death notice reported that he was still a sales representative for Getting & Fromm at the time of his death.

Richard Blum death notice

July 9, 1961 Chicago Tribune, p. 71

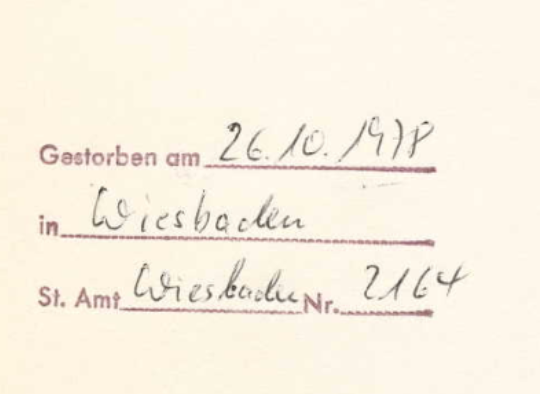

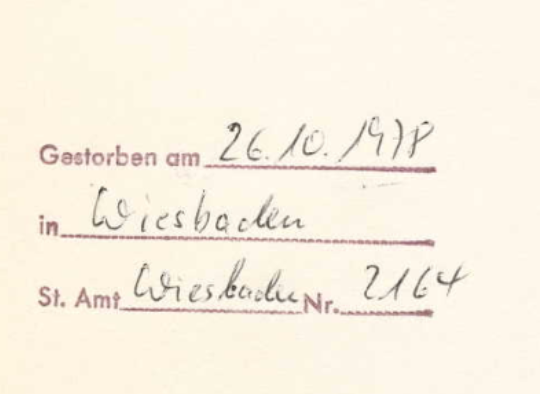

Walter died on October 26, 1978, in Wiesbaden, German, according to a notation on his birth record; interestingly, he apparently had returned to live in Germany, as the US Social Security Death Index reported his last residence as Frankfurt, Germany.

Snip from Walter Blum Morrow’s birth record; Walter Blum birth record

August 4, 1893

Ancestry.com. Mainz, Germany, Birth Records, 1872-1900 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

Original data: Personenstandsregister Geburtenregister 1876-1900. Digital images. Stadtarchiv Mainz, Mainz, Germany.

Meanwhile, their older brother Willy, known as Wilhlem and then William, had immigrated to England. Although I don’t have any records showing when William left Germany, I believe that he must have been living in England before 1943, as his mother Camilla Sichel Blum died in York, England, in 1943 (England & Wales, Death Index, 1916-2006). William is listed as living in York on a 1956 UK passenger ship manifest for a ship departing from New York and sailing to Southampton, England. I assume that Camilla had been living in York with her oldest son, William, at the time of her death in 1943.

Willliam Blum 1956 ship manifest,

The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and successors: Inwards Passenger Lists.; Class: BT26; Piece: 1364; Item: 65

That 1956 manifest reports that William was married, a wine merchant, living at 13 Maple Grove, Fulford Road, York, England, and a citizen and permanent resident of England. I also found him listed in several phone books at the same address from 1958 until 1964. Aside from that I have no records of his whereabouts or his family or his death. I don’t know whether he was involved in the Sichel wine business or a different wine company. I also don’t know whether he was married or had children. I have contacted the York library and have requested a search of the newspapers and other records there, so hope to have an update soon.

As for the sons of Hermann Sichel and Maria Trier, they appear to have remained more directly connected to the Sichel wine business than their Blum cousins. Walter Adolph Sichel, the older brother, was in charge of the British side of the Sichel import business. According to an article from the January 31, 1986 edition of The (London) Guardian (p. 10), Walter first came to England in 1928:

Anti-German feeling still lingered when young Sichel came to Britain in 1928 and travelled the country with his case of sample bottles from the family firm, H. Sichel Sohne of Mainz. Youthful persistence apart, he was lucky to have with him some of “the vintage of the century,” 1921. Potential customers found his wines easy to like, but impossible to pronounce.

(“The nun in the blue habit with something to smile about,” The (London) Guardian, January 31, 1986, p. 10)

Walter had moved permanently to England by 1935, as he is listed in the London Electoral Register for that year; also, he gave a London address on a ship manifest dated January 16, 1935.

Walter Sichel, 1935 ship manifest,

Year: 1935; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: T715, 1897-1957; Microfilm Roll: Roll 5597; Line: 1; Page Number: 93

Description

Ship or Roll Number : Roll 5597

Source Information

Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957

In December 1936, Walter Sichel married Johanna Tuchler in Marylebone, England; Johanna (known as Thea) was born in 1913 in Berlin. (Ancestry.com. England & Wales, Civil Registration Marriage Index, 1916-2005)

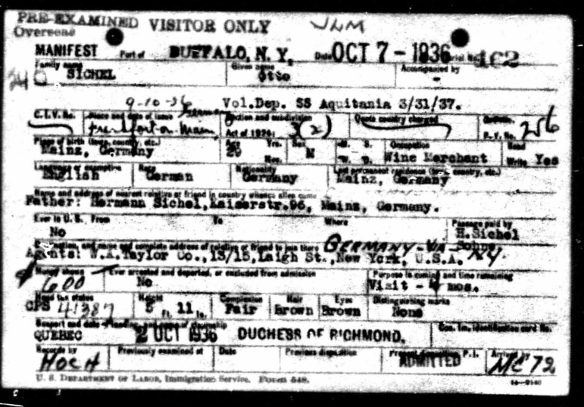

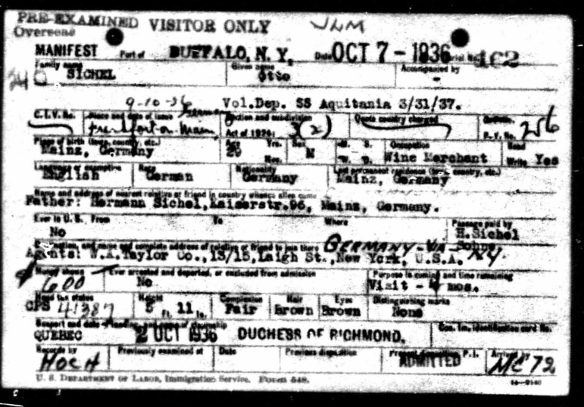

Walter Sichel’s younger brother, Ernst Otto Sichel (generally known as Otto), immigrated to the US.. He first arrived for a four month visit in October 1936, entering the country in Buffalo; he listed agents of the Taylor Company as those he was coming to see, so I assume this was a business trip with the Taylor Wine Company in upstate New York.

Ernst Otto Sichel 1936 arrival in Buffalo, NY

The National Archives at Washington, D.C.; Washington, D.C.; Manifests of Alien Arrivals at Buffalo, Lewiston, Niagara Falls, and Rochester, New York, 1902-1954; Record Group Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787 – 2004; Record Group Number: 85; Series Number: M1480; Roll Number: 127

But Otto returned to settle permanently in the US on September 30, 1937.

Otto Sichel 1937 ship manifest

Year: 1937; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: T715, 1897-1957; Microfilm Roll: Roll 6054; Line: 1; Page Number: 8

Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957

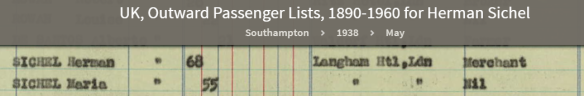

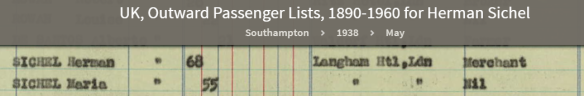

By May 1938, Hermann Sichel and Maria Trier, Otto and Walter Sichel’s parents, had also left Germany as they listed themselves as residing in London on a ship manifest when they traveled to New York on that date. In August 1939, Otto listed them on a ship manifest as residing in Buckinghamshire, England, when he sailed from New York to England at that time.

Hermann and Maria Sichel on 1938 ship manifest

Ancestry.com. UK, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012.

Original data: Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and successors: Outwards Passenger Lists. BT27. Records of the Commercial, Companies, Labour, Railways and Statistics Departments. Records of the Board of Trade and of successor and related bodies. The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, England.

Otto Sichel 1939 ship manifest—address of parents in England

Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867. Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives at Washington, D.C.

Hermann Sichel died on August 22, 1940, in Buckinghamshire. He was 71 years old; his wife Maria died in London in June 1967; she was 84. (England & Wales, Death Index, 1916-2006)

In 1940, their son Otto was listed on the US census as a paying guest in a home on East 84th Street in New York City. There was a notation on his entry that I’ve never seen before: “No response to this after many calls.” Was Otto avoiding the enumerator? Or was he just away on business?

Otto Sichel, 1940 US census

Year: 1940; Census Place: New York, New York, New York; Roll: T627_2655; Page: 2A; Enumeration District: 31-1339

Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census

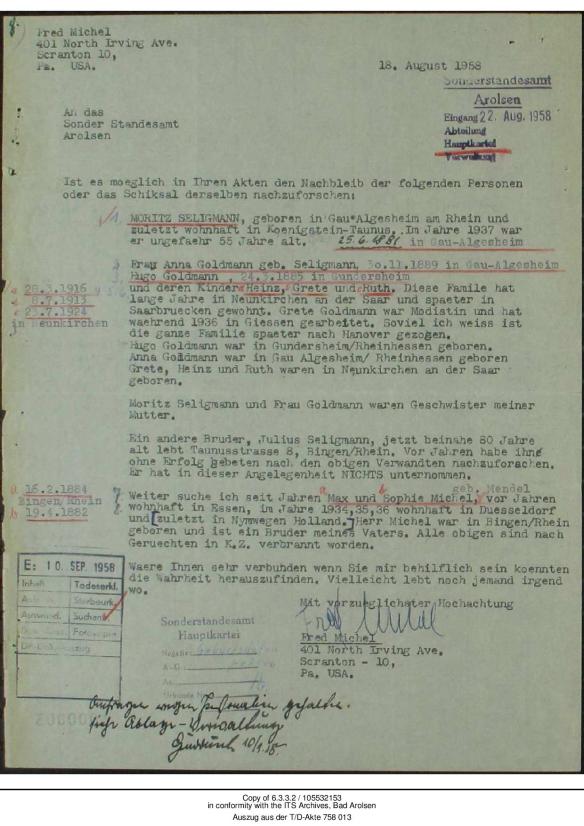

Perhaps this seeming evasiveness created some suspicion about Otto because in 1943 a request was sent by the US Immigration and Naturalization Service to the FBI to request clearance for Otto because he was “pro-German but anti-Hitler, and may be guilty of subversive activity.” I consider myself pro-American even when I do not like my country’s leaders or actions at certain times; I assume that that was how Otto felt—affection for the country of his birth, but opposed to its actions under the Nazis.

Inquiry into Otto Sichel

Ancestry.com. U.S. Subject Index to Correspondence and Case Files of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1903-1959 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010

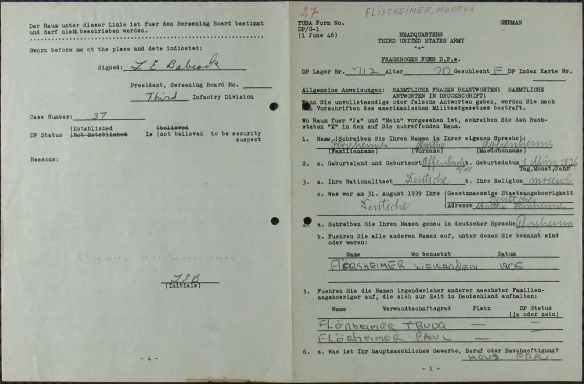

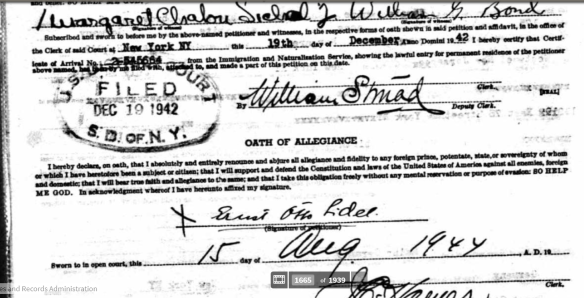

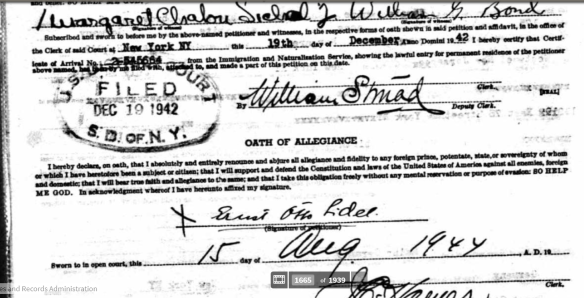

Otto must have passed the FBI investigation because on August 15, 1944, he became a naturalized citizen of the United States:

Ernst Otto Sichel naturalization papers 1944

Ancestry.com. Selected U.S. Naturalization Records – Original Documents, 1790-1974 [

On January 3, 1942, Otto married Margarete Frances Chalon in Westwood, New Jersey; Margarete was born in New York in 1919; she was 22 when they married, and Otto was 34. The marriage did not last, and they were divorced in Florida in 1949. The following year Otto married again; his second wife was Anne Marie Mayer. She was born in Germany in 1921. Otto and Anne Marie eventually moved to Port Washington, New York.

Otto died on May 10, 1972, in San Francisco. He was 65 years old. According to his obituary, he was the vice-president of Fromm & Sichel, a subsidiary of Jos. E. Seagram & Sons, at the time of his death and had been working for that company for twenty years. “E. Otto Sichel Dies; Wine Expert Was 65,” The New York Times, May 13, 1972 (p. 34).

Without going into the full corporate history, there are obvious links here between the various Sichel/Blum cousins—Richard Blum worked for the Chicago wine distributor Geeting & Fromm, which was founded in part by Paul Fromm, whose brother Alfred Fromm and Franz Sichel, first cousin of Walter Sichel and Richard Blum, founded the company where Walter Sichel worked, the San Francisco wine distributor Fromm & Sichel .

Finally, to bring this story back to its beginning, both Walter Blum and Otto Sichel listed a Mr. I(saac) Heller (“Hella” as spelled on Walter’s manifest) as the person sponsoring them in the US when they immigrated to the US in the 1930s:

Walter Blum 1939 manifest naming I Hella as friend going to in US

Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867

Isaac Heller named as person Otto Sichel was going to on 1937 manifest

Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867. Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives at Washington, D.C.

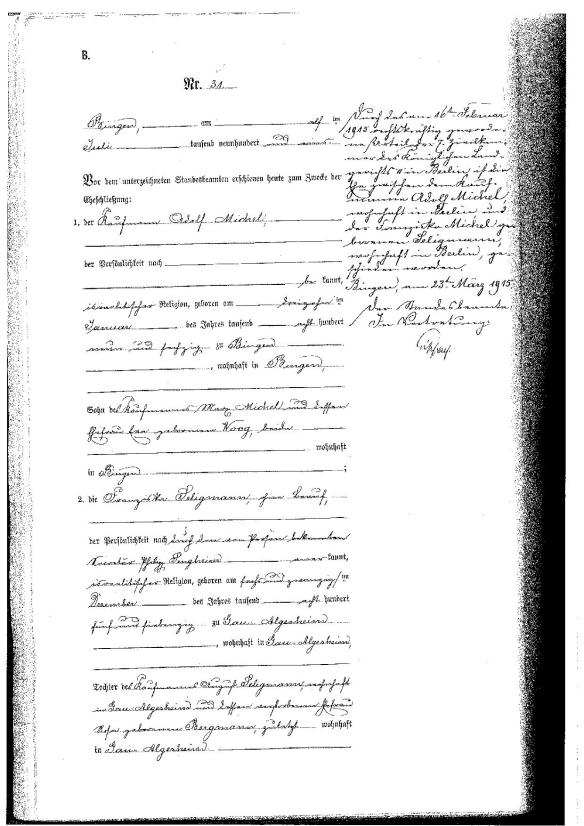

Who was this friend Isaac Heller?

He was the brother of Leanora Heller Morreau. Yes, the Leanora I had researched back in 2014 to try and understand why she had tried to rescue Bettina Seligmann Arnfeld from Nazi Germany. The same Leanora whose husband Albert was the grandson of Caroline Seligmann Morreau and a first cousin of Camilla Sichel Blum, Walter’s mother, and Hermann Sichel, Otto’s father.

Leanora may not have been able to help her late husband’s cousin Bettina Seligmann Arnfeld, but obviously she and her brother Isaac were able to help Albert’s cousins Walter Blum and Otto Sichel.

And so I lift a glass of wine (not Blue Nun, preferably a prosecco) to toast Leanora Heller Morreau! L’chaim!

[1] Unfortunately, the online records for Sprendlingen do not cover the years before 1870, and although there are some death records for the 1900s, the year 1900 is not included.